Abstract

Previously we have described a constitutively active Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation channel in freshly dispersed rabbit ear artery myocytes that has similar properties to canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) channel proteins. In the present study we have investigated the transduction pathways responsible for stimulating constitutive channel activity in these myocytes. Application of the pharmacological inhibitors of phosphatidylcholine-phospholipase D (PC-PLD), butan-1-ol and C2 ceramide, produced marked inhibition of constitutive channel activity in cell-attached patches and also butan-1-ol produced pronounced suppression of resting membrane conductance measured with whole-cell recording whereas the inactive isomer butan-2-ol had no effect on constitutive whole-cell or channel activity. In addition butan-1-ol had no effect on channel activity evoked by the diacylglycerol (DAG) analogue 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG). Inhibitors of PC-phospholipase C (PC-PLC) and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) had no effect on constitutive channel activity. Application of a purified PC-PLD enzyme and its metabolite phosphatidic acid to inside-out patches markedly increased channel activity. The phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase (PAP) inhibitor dl-propranolol also inhibited constitutive and phosphatidic acid-induced increases in channel activity but had no effect on OAG-evoked responses. The DAG lipase and DAG kinase inhibitors, RHC80267 and R59949 respectively, which inhibit DAG metabolism, produced transient increases in channel activity which were mimicked by relatively high concentrations (40 μm) of OAG. The protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor chelerythrine did not prevent channel activation by OAG but blocked the secondary inhibitory response of OAG. It is proposed that endogenous DAG is involved in the activation of channel activity and that its effects on channel activity are concentration-dependent with higher concentrations of DAG also inhibiting channel activity through activation of PKC. This study indicates that constitutive cation channel activity in ear artery myocytes is mediated by DAG which is generated by PC-PLD via phosphatidic acid which represents a novel activation pathway of cation channels in vascular myocytes.

We have previously described a constitutively active Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation current (Icat) in freshly dispersed rabbit ear artery myocytes (Albert et al. 2003) which has been proposed to contribute to resting membrane conductance (Albert et al. 2003; Albert & Large, 2004). In addition it has been shown that the neurotransmitter noradrenaline enhances this conductance and therefore Icat may also contribute to sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction (Albert & Large, 2004). Constitutively active cation conductances have also been described in other smooth muscle preparations (Bae et al. 1999; Thorneloe & Nelson, 2004) indicating that these cation channels may have important roles in regulating cellular excitability in different cell types.

There are some notable similarities between constitutively active Icat in ear artery myocytes and noradrenaline-evoked Icat in rabbit portal vein (Helliwell & Large, 1997; Albert et al. 2003; Albert & Large, 2004; Albert & Large, 2003) which involves a member of the canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) channel proteins (TRPC6) (Inoue et al. 2001). These similarities suggest that Icat in ear artery may also be composed of TRPC channel proteins but important differences in its constitutive nature and single channel properties suggest that in ear artery Icat is unlikely to be simply TRPC6.

In all cell types a key question concerns the mechanisms of activation of native TRPC-like channels as most studies have investigated activation of TRPC proteins expressed in cell lines. In rabbit ear artery, studies on the transduction mechanism underlying activation of Icat have shown a complex regulation by diacylglycerol (DAG). The DAG analogue 1-oleoyl-2-aceyl-sn-glycerol (OAG) produced both excitation and inhibition of Icat (Albert et al. 2003; Albert & Large, 2004) with activation of Icat produced via a protein kinase C (PKC)-independent mechanism whereas channel inhibition by OAG was mediated through activation of PKC. The inhibitory pathway is tonically active and it was shown that the transduction pathway leading to stimulation of PKC and inhibition of channel activity involved the classical phosphatidylinositol cascade system coupled to Gαq/Gα11 G-proteins (Albert & Large, 2004). An important observation was that the phosphatidylinositol-phospholipase C (PI-PLC) inhibitor U73122 always enhanced Icat by removing the inhibitory pathway indicating that PI-PLC is not pivotal for channel activation in ear artery unlike its essential role in activating Icat in rabbit portal vein (Helliwell & Large, 1997) and many TRPC proteins expressed in cell lines (Clapham et al. 2001). Therefore, in ear artery myocytes it is possible that another phospholipase is involved in generating DAG or that endogenous DAG does not produce channel opening.

In the present work we provide evidence that a transduction pathway involving phosphatidylcholine-phospholipase D (PC-PLD) and phosphatidic acid are involved in generating constitutive activity in ear artery and that DAG rather than its metabolites is pivotal for producing channel opening. This pathway represents a novel activation mechanism of cation channels in vascular myocytes.

Methods

Cell isolation

New Zealand White rabbits (2–3 kg) were killed by an i.v. injection of sodium pentobarbitone (120 mg kg−1) in accordance with the UK Animals Scientific Procedures Act, 1986, and ear arteries from both ears were removed. The ear arteries were freshly dispersed using procedures previously described (Albert et al. 2003; Albert & Large, 2004).

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell and single channel currents were recorded with an Axopatch 200B patch clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA) at room temperature (20–25°C) using whole-cell recording, cell-attached and inside-out configurations of the patch-clamp technique (Hamill et al. 1981). Patch pipettes were manufactured from borosilicate glass and had pipette resistances of approximately 6–10 MΩ when filled with patch pipette solution. Series resistance was not compensated. Liquid junction potentials were minimized using an agar bridge and were calculated to be < 3 mV and therefore were not compensated for in the final records. The solution in the bath chamber (0.5 ml) was changed by two syringes in a ‘push–pull’ system and full solution exchange occurred within 20–30 s. Between solution changes the perfusion of the bath chamber remained stationary which reduced line noise to improve signal to noise ratio.

To evaluate current–voltage (I–V) characteristics of whole-cell currents, membrane potential was stepped to −150 mV for 50 ms from a holding potential of −50 mV before a voltage ramp was applied to +100 mV (0.5 V s−1). The voltage ramps were generated and data captured with a Pentium III personal computer using a Digidata 1322A acquisition system and pCLAMP software (Version 9.0, Axon Instruments) at a sample rate of 5 kHz and with filtering set at 1 kHz.

To evaluate I–V curves of single channel currents the membrane potential was manually changed from a holding potential of −50 mV to between −70 mV and +50 mV. Single channel currents were initially recorded onto a DAT recorder (DRA-200, Biologic Scientific Instruments) at a bandwidth of 5 kHz and a sample rate of 48 kHz. For off-line analysis channel currents were re-digitized by filtering events at 1 kHz (−3 db, low pass 8-pole Bessel filter, Frequency Devices, model LP02, Scensys) and acquiring these events onto a Pentium III personal computer using a Digidata 1322A acquisition system and pCLAMP software (Version 9.0, Axon Instruments) at a sample rate of 10 kHz.

Mean channel current amplitudes were calculated from idealized traces produced from raw data of at least 10s duration which had a stable baseline using the 50% threshold method. The 50% threshold value was set between the baseline and the lowest open level and therefore only transitions above this value were registered as being an open channel. To maximize the number of channels reaching their full amplitude, a channel was only registered as being open if it had a duration of > 0.664 ms (calculated from two times the rise time of the 1-kHz low-pass filter used) which enabled over 90% of each event amplitude to be resolved (Colquhoun, 1987).

I–V relationships of single channel currents were derived from peak values obtained from channel current amplitude histograms created by Gaussian curves from individual patches and mean (± s.e.m.) values were calculated for each membrane potential. Pooled mean I–V relationships were then plotted and unitary conductance and reversal potential (Er) were determined by linear regression (Origin software 6.1, OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA). As we could not accurately determine the number of channels in a patch we measured channel activity by calculating open probability (NPo) at maximum or minimum channel activity using: NPo = sum of open times of channel levels above 50% threshold/sample duration. Relative NPo values were calculated by dividing the NPo value in the presence of an agent by the control NPo value.

Solutions and drugs

In whole-cell recording experiments cells were bathed in a K+-free external solution containing (mm): NaCl 126, CaCl2 1.5, Hepes 10, glucose 11, 4,4′-diisothiocyanostilbene-2–2′-disulphonic acid (DIDS) 0.1, niflumic acid 0.1 and nicardipine 0.005; pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH (267 ± 5 mosmol l−1). The whole-cell pipette solution contained (mm): CsCl 18, caesium aspartate 108, MgCl2 1.2, Hepes 10, glucose 11, BAPTA 10, CaCl2 1 (free internal calcium concentration approximately 14 nm as calculated using EQCAL software), Na2ATP 1 and NaGTP 0.2; pH adjusted to 7.2 with Tris (300 ± 5 mosmol 1−1). In cell-attached patch experiments membrane potential was set at 0 mV by perfusing cells with a KCl external solution containing (mm): KCl 126, CaCl2 1.5, Hepes 10 and glucose 11; pH adjusted to 7.2 with 10 m KOH. Nicardipine (5 μm) was included to prevent smooth muscle cell contraction by blocking Ca2+ entry through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. The cell-attached patch pipette solution was K+-free and contained (mm): NaCl 126, CaCl2 1.5, Hepes 10, glucose 11, tetraethylammonium (TEA)-Cl 10, 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) 5, DIDS 0.1, niflumic acid 0.1 and nicardipine 0.005; pH adjusted to 7.2 with 10 m NaOH. Inside-out patches were perfused with a bathing solution (i.e. intracellular solution) containing (mm): CsCl 18, caesium aspartate 108, MgCl2 1.2, Hepes 10, glucose 11, BAPTA 1, CaCl2 0.1 (free internal calcium concentration approximately 14 nm as calculated using EQCAL software), Na2ATP 1 and NaGTP 0.2; pH adjusted to 7.2 with Tris. The inside-out patch pipette solution (i.e. extracellular solution) contained (mm): NaCl 126, CaCl2 1.5, Hepes 10 and glucose 11; pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH.

D-609 has been shown to be an inhibitor of PC-PLC with a concentration to inhibit enzyme activity by 50% (IC50) of 10 μm (Monick et al. 1999) and we used this agent at concentrations of 10 μm and 100 μm. Propranolol was used as an inhibitor of phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase (PAP) at a concentration of 500 μm (IC50, ∼ 70 μm, Billah et al. 1989). Propranolol was dissolved in distilled H20 to make a stock solution of 20 mm before diluting in bathing solution to the final concentration. The PC-PLD inhibitor butan-1-ol (IC50, ∼ 16 mm, Marchesan et al. 2003; Hu & Exton, 2005) and its inactive isomer butan-2-ol (Marchesan et al. 2003) were made up as a 0.5% solution in bathing medium. Another PC-PLD inhibitor C2 ceramide (IC50, ∼ 40 μm, Abousalham et al. 1997; Singh et al. 2001), the PLA2 inhibitor AACOCF3 (IC50, ∼ 15 μm, Street et al. 1993; Ackermann et al. 1995), OAG, R59949 (IC50 for DAG kinase, ∼ 0.2 μm, De Chaffoy de Courelles et al. 1989) and RHC80267 (IC50 for DAG lipase, ∼ 4 μm, Sutherland & Amin, 1982) were dissolved in DMSO so that the final concentration of DMSO in the bathing solution was < 0.2%. Phosphatidic acid was dissolved in chloroform so that the final concentration of bathing solution was < 0.2%. Solutions of phosphatidic acid were continually sonicated for at least 15 min before application. Control experiments showed that 1% DMSO or 1% chloroform had no effect on constitutive channel activity. In experiments to investigate the effect of PKC, the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine was added to the bathing solution for 1–2 min prior to the experiment. In experiments on the steady-state dose–response effects of OAG-evoked responses, NPo was measured about 4–5 min after the peak response of each concentration of OAG. The values are the mean of n cells (±s. e. m.) and statistical analysis was carried out using Student's t test (paired and unpaired) with the level of significance set at P < 0.05.

Results

Effect of agents that inhibit PLD on constitutive channel activity in ear artery myocytes

In vascular smooth muscle it is well established that DAG may be produced from phosphatidylcholine (PC) by several pathways including PC-PLD via phosphatidic acid and also by PC-PLC (see review by Ohanian et al. 1998). Therefore in the first series of experiments we studied the effect of the pharmacological agents butan-1-ol and C2 ceramide which have previously been shown to inhibit PC-PLD activity in biochemical studies (Abousalham et al. 1997; Singh et al. 2001; Marchesan et al. 2003; Hu & Exton, 2005; see Methods).

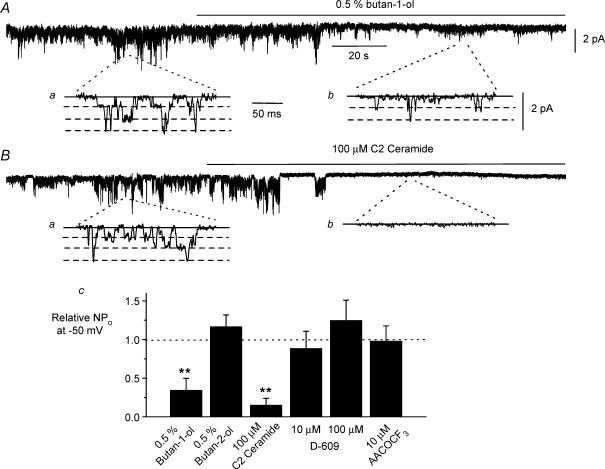

Figure 1A shows that bath application of 0.5% butan-1-ol produced a marked suppression of constitutive channel activity by about 60% in cell-attached patches at −50 mV and mean data are shown in Fig. 1C. Figure 1Aa and b show single channel current records on a more rapid timescale which had three amplitude levels reflecting three unitary conductance values as previously described (Albert et al. 2003; Albert & Large, 2004). In contrast, the isomer butan-2-ol at the same concentration, which does not inhibit PC-PLD activity (Marchesan et al. 2003), did not reduce channel activity (Fig. 1C). In addition bath application of 100 μm C2 ceramide also caused profound inhibition of constitutive channel activity by about 90% in cell-attached patches (Fig. 1B and C).

Figure 1. Effect of agents that inhibit phospholipase D on constitutive channel activity in cell-attached patches.

A, bath application of 0.5% butan-1-ol produced a marked inhibition of constitutively active channel currents. a and b, show channel currents on a faster timescale from the corresponding positions on the above brace. B, bath application of 100 μm C2 ceramide also produced a pronounced inhibition of constitutive channel activity. C, mean data of effect of butan-1-ol (n = 8), butan-2-ol (n = 5), C2 ceramide (n = 5), D-609 (n = 6) and AACOCF3 (n = 6) on relative peak NPo of constitutive channel activity. Measurements were made 2 min after application of the pharmacological agent. Holding potential was –50 mV **P < 0.01.

To test the selectivity of butan-1-ol we investigated its effect on channel currents evoked by OAG and in these experiments channel activity induced by 5 μm OAG was not significantly changed in the presence of 0.5% butan-1-ol with the relative mean NPo of OAG-evoked channel activity being 1.016 ± 0.437 (n = 5, P > 0.05) after 2 min of co-application with 0.5% butan-1-ol. These results indicate that the site of action of butan-1-ol is upstream from the effect of DAG on the ion channel and that butan-1-ol is not acting as a non-selective blocker of Icat.

We also investigated the role of other phospholipases in regulating constitutive channel activity in ear artery myocytes by studying the effect of established pharmacological inhibitors of PC-PLC and PLA2 activity. Bath application of 10 μm and 100 μm D-609, an inhibitor of PC-PLC (Monick et al. 1999), for 2 min had no effect on constitutive channel activity at −50 mV (Fig. 1C). In addition bath application of 100 μm AACOCF3, an inhibitor of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (Street et al. 1993; Ackermann et al. 1995), also had no effect on constitutive channel activity after 2 min (Fig. 1C). These data suggest that PC-PLC and PLA2 do not have major roles in regulating constitutive channel activity in ear artery myocytes.

These results suggest that PC-PLD is involved in generating constitutive channel activity in this preparation and moreover the level of inhibition of channel activity produced by butan-1-ol and C2 ceramide on constitutive channel activity is similar to the level of PC-PLD inhibition produced by the concentrations used of these agents in biochemical studies (see Methods and Discussion).

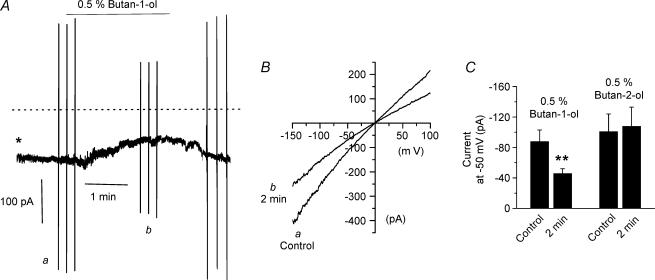

The effect of butan-1-ol on whole-cell conductance

To examine the role of PC-PLD in mediating resting membrane conductance we studied the effect of butan-1-ol on constitutively active whole-cell currents at −50 mV. Figure 2A shows that bath application of 0.5% butan-1-ol produced a reduction in constitutive whole-cell current by about 50% (Fig. 2A and C) after about 2 min whereas application of the inactive isomer butan-2-ol at the same concentration had no effect (Fig. 2C). Current–voltage (I–V) relationships of constitutive whole-cell currents determined before and after application of butan-1-ol for 2 min illustrate that this PC-PLD inhibitor reduced current amplitudes at all membrane potentials (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Effect of butan-1-ol on resting whole-cell currents.

A, bath application of 0.5% butan-1-ol reduced the amplitude of constitutively active whole-cell currents. *whole-cell configuration achieved at this time. Dashed line indicates 0 pA holding current. Holding potential was –50 mV. B, I–V relationship of whole-cell currents measured before (a) and 2 min after (b) application of 0.5% butan-1-ol. C, mean data of whole-cell currents in the presence of 0.5% butan-1-ol (n = 6) and 0.5% butan-2-ol (n = 6). **P < 0.01.

The above data provide strong evidence that a PC-PLD-mediated transduction pathway is involved in activating Icat in ear artery myocytes and regulates the resting membrane conductance.

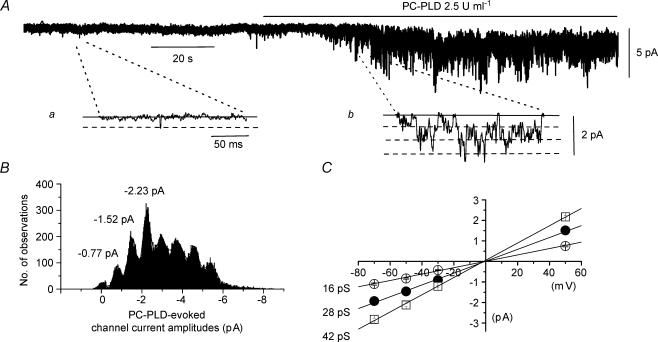

Effect of PC-PLD and phosphatidic acid on channel activity in inside-out patches

We further examined the action of PC-PLD on Icat by applying a purified PC-PLD enzyme to inside-out patches. Bath application of 2.5 U ml−1 PC-PLD from Streptomyces chromofusus produced a pronounced enhancement of constitutive channel activity (Fig. 3A) with mean peak NPo values of PLD-induced activity of 3.427 ± 0.783 (n = 9) for 2.5 U ml−1 and 2.899 ± 0.817 (n = 7) for 25 U ml−1 at −50 mV. Amplitude histograms for PLD-induced channel currents had three unitary amplitude peaks (Fig. 3B) which are shown on a faster timescale in Fig. 3Ab and these three amplitude levels were represented by three unitary conductance states of 16, 28 and 42 pS which all had a reversal potential (Er) of about 0 mV (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Effect of PC-PLD on channel activity in inside-out patches.

A, bath application of 2.5 U ml−1 PC-PLD increased constitutive channel activity in an inside-out patch at a holding potential of −50 mV; a and b, show channel currents on a faster timescale. B, amplitude histogram of PC-PLD-induced channel currents shown in A had three current amplitude levels which are represented by three conductance states of 16, 28 and 42 pS in pooled mean I–V relationships shown in C. Channel current amplitudes greater than the three unitary levels represent more than one channel in the patch.

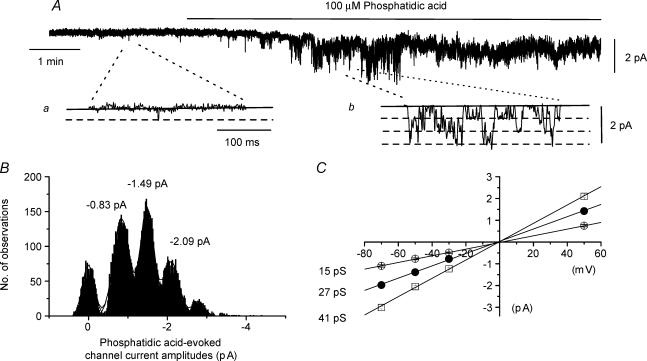

In vascular myocytes, hydrolysis of PC by PC-PLD produces phosphatidic acid which is converted to DAG by the enzyme PAP (Ohanian et al. 1998) and therefore we tested whether phosphatidic acid also had an effect on Icat. Bath application of 100 μm phosphatidic acid produced a marked increase in constitutive channel activity in inside-out patches (Fig. 4A) with a mean peak NPo of 0.997 ± 0.244 at −50 mV (n = 6). Figure 4B shows channel current amplitude histograms of phosphatidic acid-induced activity illustrated in Fig. 4Ab on a faster timescale and the mean conductance states were 15, 27 and 41 pS with an Er of about 0 mV (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Effect of phosphatidic acid on channel activity in inside-out patches.

A, bath application of 100 μm phosphatidic acid increased constitutive channel activity in an inside-out patch at a holding potential of −50 mV; a and b, show channel currents on a faster timescale. B, amplitude histogram of phosphatidic acid-induced channel currents shown in A had three current amplitude levels which are represented by three conductance states of 15, 27 and 41 pS in pooled mean I–V relationships shown in C. In B channel current amplitudes greater than the three levels represent more than one channel in the patch.

Effect of DL-propranolol on channel activity in inside-out patches

The final step in the production of endogenous DAG by PC-PLD is conversion of phosphatidic acid into DAG by PAP and therefore we tested the effect of dl-propranolol, a known effective inhibitor of PAP activity (Billah et al. 1989), on channel activity. It would be predicted that if opening of constitutive channels is due to PC-PLD-mediated production of endogenous DAG via phosphatidic acid then constitutive channel activity and phosphatidic acid-induced increases in activity should be inhibited by dl-propranolol whereas dl-propranolol should have no effect on OAG-induced activity.

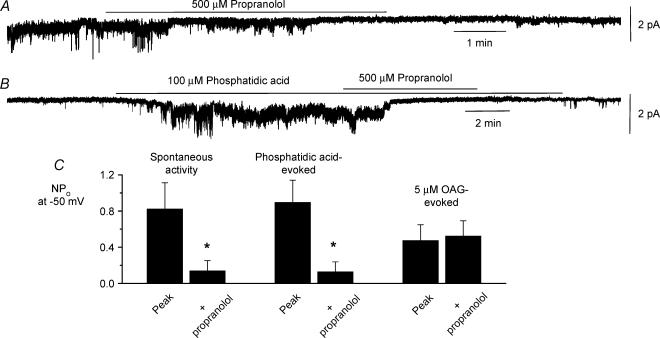

Figure 5A and B shows that bath application of 500 μmdl-propranolol reversibly inhibited constitutive activity and phosphatidic acid-induced activity in inside-out patches after about 5 min, and Fig. 5C shows the mean data with dl-propranolol decreasing these responses by about 85%. Figure 5C also shows that bath application of dl-propranolol had no effect on activity induced by 5 μm OAG (a concentration chosen to produce sustained effects, see Fig. 7A).

Figure 5. Effect of DL-propranolol on constitutive, phosphatidic acid-induced and OAG-evoked channel activity.

Effect of bath application of 500 μmdl-propranolol on constitutively active cation channel activity (A) and phosphatidic acid-induced channel activity (B) in different inside-out patches at a holding potential of −50 mV. C, mean data showing that co-application of 500 μmdl-propranolol significantly inhibited constitutively active (n = 6) and phosphatidic acid-induced (n = 6) channel activity but not OAG-induced channel activity (n = 6) after 5 min *P < 0.05.

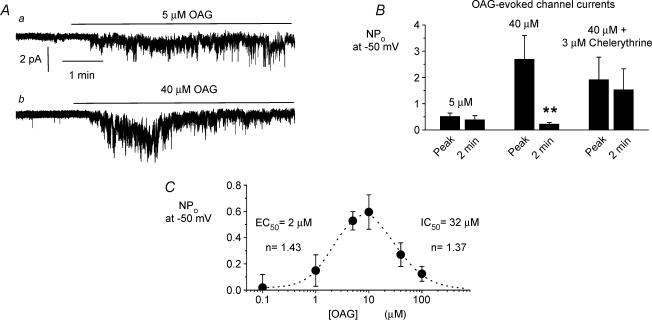

Figure 7. Effect of exogenous OAG on constitutive channel activity in cell-attached patches.

Aa, bath application of 5 μm OAG induced a sustained increase in constitutive channel activity whereas bath application of 40 μm OAG (Ab) induced a larger but transient increase in constitutive channel activity. B, mean data of OAG-induced channel activity either at the peak response or about 2 min after peak response. Note that 5 μm OAG induced a sustained response (n = 5) whereas 40 μm OAG produced a transient increase in channel activity (n = 6) that was converted to a sustained response by pretreatment with 3 μm chelerythrine for 2 min (n = 6). C, steady-state concentration–effect curve of OAG-induced responses on channel activity measured approximately 4–5 min after OAG application (i.e. with OAG concentration > 10 μm), after the peak increase in channel activity. The curves yielded an apparent EC50 of about 2 μm and an apparent IC50 of about 32 μm (each point was determined from at least five patches). **P < 0.01.

These effects of dl-propranolol provide further evidence that constitutive activity and phosphatidic acid-induced channel activity require the conversion of phosphatidic acid to DAG to produce channel opening. The lack of an effect of dl-propranolol on OAG-induced channel activity shows that dl-propranolol even at a relatively high concentration is not acting as a non-specific channel blocker.

The above data provide compelling evidence that a PC-PLD-mediated pathway involving phosphatidic acid activates Icat in ear artery myocytes and raises a key question as to the nature of the molecule that is involved in activating Icat. Therefore the next series of experiments investigated the effect of agents that inhibit DAG metabolism on Icat in order to establish whether endogenous DAG, or a DAG metabolite, is involved in regulating channel opening.

Effect of agents that inhibit DAG metabolism on constitutive whole-cell and single channel currents

The metabolism of DAG in vascular smooth muscle is controlled by two major metabolic pathways involving the enzymes DAG lipase and DAG kinase which lead to production of DAG metabolites arachidonic acid and phosphatidic acid, respectively (Ohanian et al. 1998). Therefore we studied the effect of RHC80267 and R59949, which inhibit DAG lipase and DAG kinase, respectively, on constitutively active whole-cell and single channel currents.

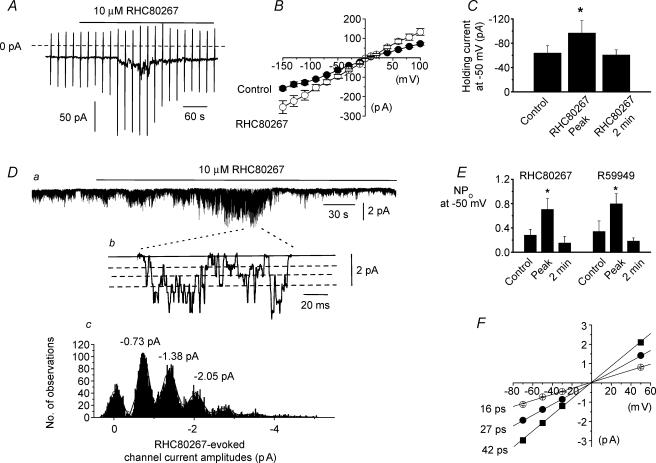

Bath application of 10 μm RHC80267 enhanced constitutively active whole-cell currents by a mean peak amplitude of −33 ± 8 pA (n = 6, Fig. 6A and C) at a holding potential of −50 mV. Following RHC80267-induced increase in constitutive activity the amplitude of the whole-cell currents then declined to a level similar to that recorded prior to application of RHC80267 (Fig. 6A and C). The mean I–V relationship of the RHC80267-induced increase in constitutive activity was enhanced at all membrane potentials and had an Er of about 0 mV (Fig. 6B). Bath application of 10 μm RHC80267 had a similar effect on constitutively active channel currents recorded in cell-attached patches with an initial increase followed by a decrease in activity (Fig. 6D and E). Figure 6Dc shows that the amplitude histogram of these RHC80267-induced channel currents contained three unitary amplitudes which represented conductance states of 16, 27 and 42 pS which all had an Er of about 0 mV (Fig. 6F). Current channel amplitude histograms created before and after application of RHC80267 had similar peak values suggesting RHC80267 enhanced the opening of the same constitutively active channel currents. We also investigated the effect of the DAG kinase inhibitor R59949 on constitutive channel currents in cell-attached patches. Application of 10 μm R59949 also induced a biphasic effect on Icat similar to the effect of RHC80267 (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6. Effect of inhibitors of DAG metabolism on constitutively active whole-cell and single channel cation currents in ear artery myocytes.

A, bath application of 10 μm RHC80267 induced a transient increase in whole-cell current. Note that the increase in holding current followed by a decrease in activity are associated with, respectively, an increase and then decrease in ‘noisy’ appearance. Holding potential was −50 mV. The dashed line represents 0 pA holding current and vertical lines represent current responses to membrane potential ramps from −150 mV to +100 mV. B, mean I–V relationships of whole-cell currents in the absence and presence of 10 μm RHC80267 (n = 6). C, mean data of RHC80267-induced whole-cell currents (n = 6). Da, in a cell-attached patch bath application of 10 μm RHC80267 induced an initial increase in constitutive channel activity followed by a decrease in activity. Holding potential at −50 mV. Note in this patch that the RHC80267-induced decrease in channel activity after peak NPo is less than control activity. Db, expanded timescale of a section of trace shown in a. Bold line represents closed level and three dashed lines represent three conductance levels. Larger amplitude openings represent more than one channel in the patch. Dc, histogram of RHC-induced channel current amplitudes showing channels opened to three current levels. Channel amplitudes greater than these levels were due to more than one channel in the patch. E, mean data of 10 μm RHC80267-induced (n = 10) and 10 μm R59949-induced channel activity (n = 7). F, pooled mean I–V relationship of RHC80267-induced channel currents showing the three current amplitude levels represented three conductances of 16, 27 and 42 pS (each point was determined from at least five patches). *P < 0.05.

Effect of exogenous OAG on constitutive channel activity in cell-attached patches

Previously we have shown that application of the DAG analogue OAG can evoke biphasic effects on Icat via PKC-independent and PKC-dependent mechanisms (Albert et al. 2003; Albert & Large, 2004) which are similar to the effects of RHC80267 and R59949 shown in the present work. The biphasic effects of these agents may be due to different DAG concentrations activating the PKC-independent and dependent mechanisms and we therefore investigated this possibility by examining the concentration-dependence of exogenous OAG on cell-attached patches.

Figure 7Aa and B illustrate that bath application of 5 μm OAG induced an increase in constitutive channel activity in ear artery myocytes which was sustained throughout the recording duration (up to 5 min). Figure 7Ab and B show that bath application of 40 μm OAG evoked larger increases in peak channel activity than 5 μm OAG but that the peak responses were transient and declined to a significantly lower level of channel activity after 2 min. Figure 7B also shows that increases in constitutive channel activity evoked by 40 μm OAG were not altered by preincubation with the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine (3 μm) for 2 min whereas the subsequent decline in channel activity was blocked. To more accurately analyse the concentration dependence of OAG on channel activity, we plotted the steady-state concentration–response curve of OAG where NPo was measured about 4–5 min after adding OAG (i.e. after the peak response to 40 μm OAG shown in Fig. 7Ab). Figure 7C shows that bath application of OAG to cell-attached patches in low micromolar concentrations (≤ 10 μm) produced an increase, and higher concentrations decreased steady-state constitutive channel activity producing a bell-shaped concentration–response curve with an apparent EC50 (concentration to produce 50% of maximal NPo increase) of about 2 μm and an apparent IC50 (concentration to produce 50% decrease in NPo) of about 32 μm for OAG.

Discussion

In the present study we provide strong evidence that a PC-PLD-mediated transduction pathway generating phosphatidic acid and DAG is involved in producing constitutive channel activity in freshly dispersed rabbit ear artery myocytes. This signal transduction pathway is well established in many vascular preparations (see Ohanian et al. 1998) but has not previously been directly linked to activation of cation channels and therefore this study represents a novel ion channel activation mechanism. This observation is particularly notable as TRPC channel proteins which have similar properties to Icat in ear artery are frequently stated to be activated via PI-PLC-coupled mechanisms (e.g. see Clapham et al. 2001; Minke & Cook, 2002; Montell et al. 2002; Hardie, 2003; Albert & Large, 2004). This study also indicates that endogenous DAG, presumably generated from phosphatidic acid via hydrolysis of PC by PC-PLD, is of primary importance in channel opening. Moreover here we describe biphasic actions of OAG on Icat and propose that excitation predominantly occurs at low concentrations of OAG whereas at higher concentrations OAG induces a net steady-state inhibitory effect through stimulation of a PKC-dependent pathway.

Role of PC-PLD in mediating constitutive channel activity

Previously we have demonstrated that the PI-PLC inhibitor U73122 increased Icat activity in ear artery and therefore it is unlikely that PI-PLC has an important role in generating constitutive channel activity (Albert & Large, 2004). Therefore we investigated the role of other phospholipase pathways capable of generating DAG in the activation mechanisms of Icat by studying the effect of pharmacological agents that are known to inhibit the activity of different phospholipases. The present study clearly shows that the well characterized pharmacological inhibitors of PC-PLD, butan-1-ol (Marchesan et al. 2003; Hu & Exton, 2005) and C2 ceramide (Abousalham et al. 1997; Singh et al. 2001), produced marked inhibitory effects on constitutive channel activity whereas the inactive isomer butan-2-ol (Marchesan et al. 2003) had no effect. The level of inhibition produced by 0.5% butan-1-ol and 100 μm C2 ceramide on Icat was about 50% and 90%, respectively, which is similar to the level of inhibition observed in biochemical studies which have used these agents to inhibit PC-PLD activity. In these studies 0.5% butan-1-ol reduced PC-PLD activity by about 50% (Hu & Exton, 2005) and 100 μm C2 ceramide reduced PC-PLD activity by between 70% and 100% (Abousalham et al. 1997; Singh et al. 2001). Butan-1-ol did not have an effect of channel activity induced by OAG suggesting that the site of action of butan-1-ol was upstream from the action of DAG and that butan-1-ol was not having a non-selective blocking effect on Icat.

Further evidence for a role of PC-PLD in the transduction mechanism of Icat was that purified PC-PLD enzyme and phosphatidic acid, a metabolite of PC hydrolysis by PC-PLD, induced pronounced increases in channel activity when applied to the cytoplasmic surface of inside-out patches. PC-PLD- and phosphatidic acid-induced channel activity had similar conductance and Er values to constitutive channel currents previously described (Albert et al. 2003; Albert & Large, 2004) indicating that these agents increase the activity of the same channels. Also dl-propranolol, which inhibits the conversion of phosphatidic acid to DAG by suppressing PAP activity (Billah et al. 1989), markedly decreased constitutive and phosphatidic acid-induced increases in NPo but not OAG-evoked channel activity. Moreover the present results did not produce any evidence for pathways involving PC-PLC or PLA2 having major roles in activating constitutive channel activity as the PC-PLC inhibitor D-609 (Monick et al. 1999) and the PLA2 inhibitor AACOCF3 (Street et al. 1993; Ackermann et al. 1995) had no effect on constitutive channel activity. PC-PLD has been shown to be involved in mediating vasoconstrictor responses in both arterial and venous preparations (Aburto et al. 1995; Jinsi et al. 1996; Ohanian et al. 1998; Liu et al. 1999) although to our knowledge the present study is the first to describe a role of PC-PLD in regulating the activity of a biophysically characterized cation channel.

Role of endogenous DAG in activating Icat

In the present study we also explored whether endogenous DAG or DAG metabolites regulate Icat in ear artery myocytes by using inhibitors of DAG metabolism, specifically RHC80267 which inhibits DAG lipase and R59949 which is an inhibitor of DAG kinase. These agents produced a biphasic response of initial excitation followed by inhibition of Icat activity and these effects were mimicked by exogenous OAG at relatively high concentrations (≥ 40 μm) as previously described (Albert et al. 2003). In other studies on native cation channels and expressed TRPC channel proteins it has also been shown that the effects of exogenous OAG were mimicked by RHC80267 and R59949 (Helliwell & Large, 1997; Hofmann et al. 1999; Okada et al. 1999; Tesfai et al. 2001; Venkatachalam et al. 2003). These data provide strong evidence that endogenous DAG, and not a DAG metabolite, is involved in activation and inhibition of Icat. A notable result is that R59449 induced channel activity which suggests that the conversion of DAG to phosphatidic acid by DAG kinase is unlikely to have a role in mediating Icat and implies that phosphatidic acid which is shown in the present work to induce channel activation is not the direct activator of the cation channels. It should be emphasized that the present experiments do not show that DAG directly opens the channel but that DAG is the signal molecule so far identified that is closest to the channel.

Studies on the concentration-dependent effects of OAG on Icat showed that at lower concentrations (≤ 10 μm) OAG induced small but sustained increases in Icat whereas higher concentrations of OAG induced transient increases in channel activity which produced a bell-shaped steady-state concentration–response curve to OAG. These concentration-dependent effects of OAG on channel activity and the removal of the inhibitory effect of OAG by a PKC inhibitor provide a possible explanation for the biphasic actions of RHC80267 and R59949 on Icat. With relatively low concentrations excitatory actions of OAG are predominant (EC50, ∼ 2 μm) but at higher concentrations inhibitory effects of OAG via PKC become marked (IC50, ∼ 32 μm). Therefore the bimodal effects of RHC80267 and R59949 may be explained by an initial build up of endogenous DAG, through inhibition of DAG metabolism, which leads to an increase in channel activity but as DAG concentration increases further the inhibitory effect of DAG becomes evident. This is not to imply that the concentration–response curve of OAG reflects the actual dependence of channel excitation and inhibition on OAG concentration but simply the net effect. It is possible that PKC-dependent inhibition of Icat also occurs with low micromolar concentrations of OAG but the excitatory response dominates. These results may have important consequences for other studies which use relatively high concentrations of OAG to activate native TRPC-like cation channels or TRPC channel proteins expressed in cell lines.

Signal transduction pathways regulating constitutive channel activity in ear artery myocytes

The present work provides further evidence for the proposal that different excitatory and inhibitory signalling pathways converge on Icat in ear artery (Albert & Large, 2004). The present data indicate that PC-PLD-mediated hydrolysis of PC generates phosphatidic acid which is converted to DAG to produce channel opening via a PKC-independent mechanism. There is also an inhibitory pathway involving Gαq/Gα11-dependent stimulation of PI-PLC to produce DAG which inhibits channel activity via PKC (Albert & Large, 2004). Previously we have demonstrated that the G-protein inhibitor GDPβS and anti-Gαi/Gαo antibodies also reduced constitutive channel activity (Albert & Large, 2004) and therefore it is likely that constitutive Gαi/Gαo G-protein activity is linked to stimulation of PC-PLD which initiates the cascade responsible for channel activation.

We do not intend to suggest that DAG derived from PI-PLC is only used in channel inhibition or that DAG from PC-PLD is exclusively used in excitation. Indeed in a few cells butan-1-ol transiently increased channel activity prior to switching them off suggesting that DAG produced from PC-PLD may be producing channel inhibition in addition to excitation. Nevertheless there appears to be a degree of hardwiring in the signalling pathways as PI-PLC inhibition always increased channel activity (Albert & Large, 2004) and the PC-PLD inhibitors always produced marked reduction in channel activity whereas purified PC-PLD and phosphatidic acid always produced significant excitation. A possible explanation for this apparent hardwiring is that DAG produced via PI-PLC may be more closely linked to PKC than DAG generated from PC-PLD. Hence the former transduction mechanism is predominantly involved in channel inhibition.

Comparison of Icat in ear artery myocytes with TRPC6-like channels in rabbit portal vein reveals that endogenous DAG production plays a central role in channel activation in both preparations but that different biochemical pathways are utilized to generate DAG. In portal vein, activation of Icat is mediated by a PI-PLC-dependent transduction mechanism which is the classical activation pathway of many TRPC channel proteins expressed in cell lines whereas in the present study we show that in ear artery Icat is activated via a novel pathway involving PC-PLD.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the Wellcome Trust.

References

- Abousalham A, Liossis C, O'Brien L, Brindley DN. Cell Permeable ceramides prevent the activation of phospholipase D by ADP-ribosylation factor and RhoA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1069–1075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aburto T, Jinsi A, Zhu Q, Deth RC. Involvement of protein kinase C activation in alpha2-adrenoceptor-mediated contractions of rabbit saphenous vein. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;302:35–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00054-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann EJ, Conde-Frieboes K, Dennis EA. Inhibition of macrophage Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 by bromoenol lactone and trifluoromethyl ketones. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:445–450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Large WA. Synergism between inositol phosphates and diacylglycerol on native TRPC6-like channels in rabbit portal vein myocytes. J Physiol. 2003;552:789–795. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.052977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Large WA. Inhibitory regulation of constitutive transient receptor potential-like cation channels in rabbit ear artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2004;560:169–180. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.071738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Piper AS, Large WA. Properties of a constitutively active Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation channel in rabbit ear artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2003;549:143–156. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.038190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae YM, Park MK, Lee SH, Ho WK, Earm YE. Contribution of Ca2+-activated K+ channel and non-selective cation channels to membrane potential of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells of the rabbit. J Physiol. 1999;514:747–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.747ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billah MM, Eckel S, Mullmann TJ, Egan RW, Siegel MI. Phosphatidylcholine hydrolysis by phospholipase D determines phosphatidate and diaglyceride levels in chemotaxic peptide-stimulated human neutophils. Involvement of phosphatidate phosphohydrolase in signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:17069–17077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE, Runnels LW, Strubing C. The trp ion channel family. Nat Neurosci. 2001;2:387–396. doi: 10.1038/35077544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D. Practical analysis of single channel recordes. In: Standen NB, Gray PTA, Whitaker MJ, editors. Microelectrode Techniques. Cambridge: The Company of Biologists; 1987. pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- De Chaffoy de Courelles D, Roevens P, Van Belle H, Kennis L, Clerck F. The role of endogenously formed diacylgylcerol in the propagation and termination of platelet activation. A biochemical and functional analysis using novel diacylglycerol kinase inhibitor, R59949. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3274–3285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie RC. Regulation of TRP channels via lipid second messengers. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:735–759. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell RM, Large WA. α-Adrenoceptor activation of a non-selective cation current in rabbit portal vein by 1, 2-diacyl-sn-glycerol. J Physiol. 1997;499:417–428. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann T, Obukhov AG, Schaefer M, Harteneck C, Gudermann TG. Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature. 1999;397:259–263. doi: 10.1038/16711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu T, Exton JH. 1-butanol interferes with phospholipase D1 and protein kinase Calpha association and inhibit phospholipase D1 basal activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;327:1047–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R, Okada T, Onoue H, Harea Y, Shimizu S, Naitoh S, Ito Y, Mori Y. The transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP6 is the essential component of vascular α-adrenoceptor-activated Ca2+-permeable cation channel. Circ Res. 2001;88:325–337. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinsi A, Paradise J, Deth RC. A tyrosine kinase regulates alpha-adrenoceptor-stimulated contraction and phospholipase D activation in the rat aorta. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;302:183–190. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GL, Shaw L, Heagerty AM, Ohanian V, Ohanian J. Endothelin-1 stimulates hydrolysis of phoshatidylcholine by phospholipases C and D in intact mesenteric arteries. J Vasc Res. 1999;36:35–46. doi: 10.1159/000025624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchesan D, Rutberg M, Andersson L, Asp L, Larsson T, Boren J, Johansson BR, Olofsson SO. A phospholipase D-dependent process forms lipids droplets containing caveolin, adipocyte differentiation-related protein, and vimentin in a cell-free system. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27293–27300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minke B, Cook B. Trp channel proteins and signal transduction. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:429–472. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monick MM, Carter AB, Gudmundsson G, Mallampalli R, Powers LS, Hunninghake GW. A phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C regulates activation of p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinases in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 1999;162:3005–3012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C, Birnbaumer L, Flockerzi V. The trp channel, a remarkably functional family. Cell. 2002;108:595–598. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohanian J, Liu G, Ohanian V, Heagerty AM. Lipid second messengers derived from glycerolipids and sphingolipids, and their role in smooth muscle function. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998;164:533–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201x.1998.tb10703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Inoue R, Yamazaki K, Maeda A, Kurosaki T, Yamakuni T, Tanaka I, Shimizu S, Ikenaka K, Imoto K, Mori Y. Molecular and functional characterization of a novel mouse transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP7. Ca2+-permeable cation channel that is constitutively activated and enhanced by stimulation of G-protein coupled receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27359–27370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh IN, Stromberg LM, Bourgoin SG, Sciorra VA, Morris AJ, Brindley DN. Ceramide inhibition of mammalian phospholipase D1 and D2 activities is antagonized by phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11227–11233. doi: 10.1021/bi010787l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street IP, Lin HK, Laliberte F, Ghomashchi F, Wang Z, Perrier H, Tremblay NM, Huang Z, Weech PK, Gelb MH. Slow-and tight-binding of the 85-kDa human phospholipase A2. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5935–5940. doi: 10.1021/bi00074a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland CA, Amin D. Relative activities of rat and dog platelet phospholipase A2 and diglyceride lipase. Selective inhibition of diglyceride lipase by RHC 80267. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:14006–14010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesfai Y, Brereton HM, Barritt GJ. A diacylgylcerol-activated Ca2+ channel in PC12 cells (an adrenal chromaffin cell line) correlates with expression of the TRP-6 (transient receptor potential) protein. Biochem J. 2001;358:717–726. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3580717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorneloe KS, Nelson MT. Properties of a tonically active, sodium-permeable current in mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C1246–C1257. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00501.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam K, Zheng F, Gill DL. Regulation of canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) function by diacylglycerol and protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29031–29040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]