Abstract

Dicistronic reporter plasmids, such as the dual luciferase-containing pR-F plasmid, have been widely used to assay cellular and viral 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs) for IRES activity. We found that the pR-F dicistronic reporter containing the 5′ UTRs from HIF-1α, VEGF, c-myc, XIAP, VEGFR-1, or Egr-1 UTRs all produce the downstream luciferase predominantly as a result of cryptic promoter activity that is activated by the SV40 enhancer elements in the plasmid. RNA transfection experiments using dicistronic or uncapped RNAs, which avoid the complication of cryptic promoter activity, indicate that the HIF-1α, VEGF, c-myc, and XIAP UTRs do have some IRES activity, although the activity was much less than that of the viral EMCV IRES. The translation of transfected monocistronic RNAs containing these cellular UTRs was greatly enhanced by the presence of a 5′ cap, raising questions as to the strength or mechanism of IRES-mediated translation in these assays.

Keywords: IRES, translation initiation, dicistronic reporter, HIF-1α, VEGF, c-myc

INTRODUCTION

The initiation of translation in eukaryotes normally commences with the coalescence of an initiation complex at the 5′ end of the mRNA, triggered by the binding of the 5′ cap to the eIF4E subunit of the eIF4F translation initiation complex. An alternative mode of translation initiation, termed internal ribosome entry, was initially discovered as a special feature of viruses such as poliovirus, hepatitis C virus, and encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) that do not have a 5′ cap and so cannot be translated by the normal mechanism. These viruses have an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) that recruits the 43S small ribosome subunit initiation complex to the mRNA (Jang et al. 1988; Pelletier and Sonenberg 1988; Tsukiyama-Kohara et al. 1992; Wang et al. 1993). This method of translation initiation has the additional advantage for the virus of allowing production of viral proteins to occur while normal cellular translation mechanisms are inhibited in the infected cells. Conceivably, cellular proteins that are needed during stress conditions that compromise cap-dependent protein synthesis, such as hypoxia, nutrient deficiency, or apoptosis, could utilize a similar means of initiating protein production. Indeed, numerous reports have been published describing IRESs in genes encoding key regulatory proteins such as VEGF, HIF-1α, c-myc, XIAP, and various others (Akiri et al. 1998; Huez et al. 1998; Miller et al. 1998; Stein et al. 1998; Stoneley et al. 1998; Holcik et al. 1999; Lang et al. 2002).

An assay commonly used to detect IRES activity involves tranfecting cells with a plasmid containing a dicistronic gene that encodes two reporter proteins on a single mRNA transcript. A typical such reporter encodes Renilla luciferase upstream of firefly luciferase. Production of the firefly luciferase is taken as a measure of IRES activity residing in the UTR inserted between the two coding regions. However, a positive readout in the assay could potentially arise from transcription from an unsuspected cryptic promoter in the DNA that encodes the UTR or from a splicing event that removed the upstream coding region. Either event would generate a shorter, monocistronic form of the mRNA that can be translated to produce the firefly luciferase reporter protein without any need for an IRES. Researchers usually attempt to detect such short RNAs to eliminate this alternative explanation for the activity. However, the sensitivity of reporter gene assays, such as the commonly used luciferase assay, is such that even minor amounts of monocistronic transcript, which may be difficult to detect by Northern blot and RNase protection assays, might nevertheless produce detectable enzymatic activity (Hellen and Sarnow 2001). In a mini-review of the IRES literature, Kozak (2001) went so far as to propose that these considerations make most of the published reports of IRESs of questionable validity.

In a vigorous response to the Kozak mini-review it was pointed out that the evidence for the internal ribosome entry mechanism of translation in some instances, and especially for many viral IRESs, is overwhelmingly strong (Schneider et al. 2001). Nevertheless, the potential for alternative mechanisms producing a positive result in the dicistronic assay was highlighted by an investigation of what was believed at the time to be the eIF4G 5′ UTR and to contain a strong IRES (Han and Zhang 2002). In this work, it was found that although the eIF4G-derived segment generates downstream reporter activity when inserted into a dicistronic reporter gene, the bulk of this activity was due to the activation a cryptic promoter within the eIF4G region by the SV40 enhancer that is located elsewhere on the reporter plasmid. Recent reports have clarified the identity of the eIF4G 5′ UTR and shown that although translation is cap-dependent, it remains active during poliovirus infection (Byrd et al. 2002, 2005). A recent report has also shown that what was previously believed to be strong IRES activity from the 5′ UTR of the XIAP mRNA may be largely the result of activation of cryptic splicing by insertion of the XIAP UTR into a dicistronic reporter (Van Eden et al. 2004a).

Having previously found evidence of IRES activity in the 5′ UTRs of mRNAs involved in the response to hypoxia (Miller et al. 1998; Lang et al. 2002), we began an investigation to identify whether other genes involved in the response to hypoxia, such as VEGF-R1 and Egr-1, might also have IRES activity. We report here our finding from this study that these and some other genes previously described as containing IRESs have cryptic promoters in their 5′ UTRs that are activated by the viral enhancer region in the commonly used pR-F dicistronic reporter plasmid. Using RNA transfection we show that some cellular mRNAs do have IRES activity, but because the IRES activity in this assay is very low, it is not clear whether the IRES-mediated translation would compensate for a significant decrease in cap-mediated translation.

RESULTS

Evidence for cryptic promoter activity in assays using transfected dicistronic reporter plasmids

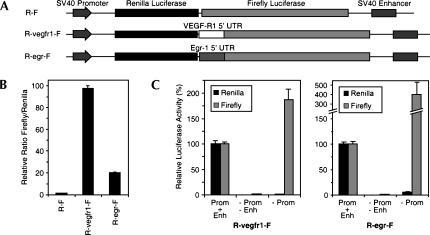

The 5′ UTRs of the VEGF receptor-1 (VEGFR-1) and Egr-1 mRNAs are relatively long and GC-rich, which we have observed to be a common feature of the 5′ UTRs of cellular mRNAs reported to have IRES activity. With the intention of investigating whether the VEGFR-1 and Egr-1 5′ UTRs have IRES activity, we made dicistronic reporter constructs in which the 5′ UTRs from the VEGFR-1 and Egr-1 mRNAs were inserted between the Renilla and firefly luciferase cistrons of the dicistronic reporter gene R-F (Lang et al. 2002). The resulting plasmids, called R-vegfr1-F and R-egr-F, respectively (Fig. 1A), were each transiently transfected into HeLa cells, and the subsequent ratio of firefly luciferase to Renilla luciferase was compared to that from the control plasmid R-F, which contains a short linker sequence between the two luciferase cistrons. The VEGF-R1 and Egr-1 5′ UTRs both increased the relative production of firefly luciferase by many-fold (Fig. 1B). This result is consistent with these mRNAs containing an IRES, but could also potentially result from cryptic promoter activity in the 5′ UTRs.

FIGURE 1.

Effect of the VEGF-R1 and Egr-1 5′ UTRs on activity of the downstream reporter in a dicistronic gene. (A) Schematic illustration of the dicistronic reporter genes R-F, R-vegfr1-F, and R-egr-F. (B) Relative enhancement of expression of the downstream reporter enzyme by the VEGF-R1 and Egr-1 5′ UTRs. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the reporter genes as indicated. Renilla and firefly luciferase activities were determined 24 h post-transfection and expressed as ratios of firefly to Renilla luciferase, relative to the ratio for R-F, which was given a value of 1. Data are presented as the mean (± SEM) of triplicate samples from three independent experiments. (C) Effect of removal of the promoter and enhancer (−Prom−Enh) or removal of just the proximal promoter (−Prom). HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the reporter genes as indicated, and Renilla and firefly luciferase activities were determined 24 h post-transfection. The amount of each luciferase activity is shown as a percentage relative to the amount produced from the intact form of the plasmid (Prom + Enh).

One of the approaches used in recent studies of cellular IRESes to indicate whether the UTR inserted in a dicistronic reporter has cryptic promoter activity is to delete the promoter that drives expression of the dicistronic reporter and confirm that both reporter activities are eliminated. To test whether the VEGFR-1 or Egr-1 UTRs can act as promoters, we deleted the entire SV40 promoter (i.e., proximal promoter and enhancer) from the reporter plasmids and examined the effect on luciferase expression in transfected HeLa cells. Deletion of the entire SV40 promoter greatly reduced the expression of both the upstream Renilla luciferase and the downstream firefly luciferase, indicating that neither the VEGFR-1 nor the Egr-1 UTR acts as an autonomous promoter in transfected HeLa cells (Fig. 1C). However, we also considered the possibility that VEGFR-1 or Egr-1 UTRs, despite not having any promoter activity in isolation, might be cryptically activated when in the proximity of the powerful enhancer elements from the SV40 promoter. To test this possibility, we made constructs in which just the proximal promoter region of the SV40 promoter was deleted, but the enhancer region was left intact. Removal of just the proximal promoter greatly reduced the expression of the upstream Renilla luciferase, but firefly luciferase continued to be expressed from the plasmids that contained the VEGFR-1 or EGR-1 5′ UTRs (Fig. 1C). This indicates that the VEGFR-1 and EGR-1 UTRs, although they do not have intrinsic promoter activity, can neverthelss be cryptically activated by the SV40 enhancer.

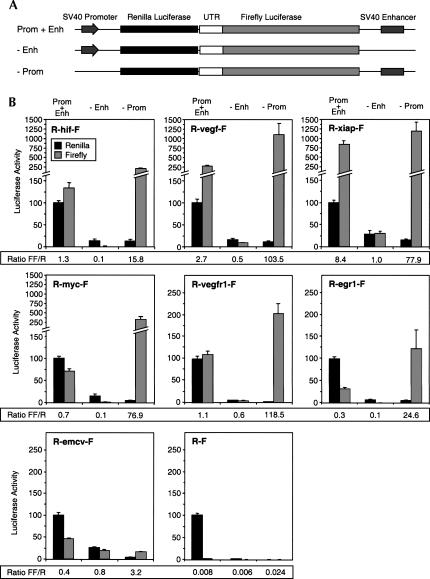

This finding prompted us to check whether a number of other cellular 5′ UTRs that have been assayed for IRES activity using this dicistronic reporter might also be subject to cryptic promoter activation. To determine whether the 5′ UTRs from the HIF-1α, VEGF, c-myc, or XIAP mRNAs are subject to cryptic activation when located in the vicinity of the SV40 enhancer, we likewise tested the effect of removing the SV40 proximal promoter from the reporter gene, but leaving the enhancer region intact. In each case, deletion of the SV40 proximal promoter caused most of the Renilla luciferase activity to be lost, as expected, but the firefly luciferase activity, rather than decreasing, was increased by up to fourfold (Fig. 2B). This indicates that the viral enhancer in the reporter plasmid activates cryptic promoters in each of these UTRs. On the other hand, deletion of the SV40 proximal promoter from a reporter gene containing the IRES from encephalomyocarditis virus resulted in a reduction in firefly luciferase activity by about half. This is consistent with at least half of firefly luciferase expressed from the intact R-emcv-F reporter plasmid being translated by IRES-dependent initiation from dicistronic mRNA.

FIGURE 2.

Cryptic promoter activity in the 5′ UTRs of HIF-1α, VEGF, c-myc, and XIAP is activated by the viral enhancer region in a dicistronic reporter plasmid. (A) Schematic illustration of the dicistronic reporter gene showing variants with or without SV40 proximal promoter or enhancer regions. (B) Effect of removal of the enhancer (−Enh) or the proximal promoter (−Prom). HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the reporter genes as indicated, and Renilla and firefly luciferase activities were determined 24 h post-transfection. The individual Renilla and firefly luciferase activities are shown, expressed as a percentage of Renilla activity from the corresponding intact dicistronic form of the plasmid. The ratios of firefly activity to Renilla activity are tabulated below the histograms. Data are presented as the mean (± SEM) of triplicate samples from at least three independent experiments.

This experiment indicated that the SV40 enhancer elicits cryptic promoter activity from the various UTRs when the SV40 proximal promoter is deleted, but does not indicate the extent of cryptic promoter activity in the intact plasmid that includes the SV40 proximal promoter. Indeed, for each construct containing a cellular UTR, the intact reporter produced less firefly luciferase activity than the reporter without the proximal promoter, suggesting that the SV40 proximal promoter competes with a cryptic promoter for interaction with the SV40 enhancer element. Deletion of the SV40 proximal promoter would remove this competition, making the enhancer more available for activation of the cryptic promoter region. When the SV40 proximal promoter is present, it is conceivable that the enhancer region interacts exclusively with this promoter region, allowing little or no activation of cryptic promoters. To test this, we asked whether the relative amounts of firefly and Renilla luciferase were affected by removal of just the enhancer. Removal of the enhancer would be expected to reduce the amount of dicistronic mRNA produced, but should not change the ratio of firefly luciferase to Renilla luciferase if both are translated from a single dicistronic mRNA. In Figure 2B the Renilla and firefly luciferase activities are each shown separately, and the ratios of firefly to Renilla are tabulated below the histograms. Removal of the enhancer produced a considerable decrease in this ratio for all the reporters containing cellular UTRs. The large effect of the enhancer on the firefly: Renilla ratio indicates that for these constructs the firefly and Renilla luciferases are predominantly produced from different transcripts. The fact that the ratio is determined by the presence or absence of an enhancer indicates the alternative transcript results from cryptic promoter activity involving the cellular UTR.

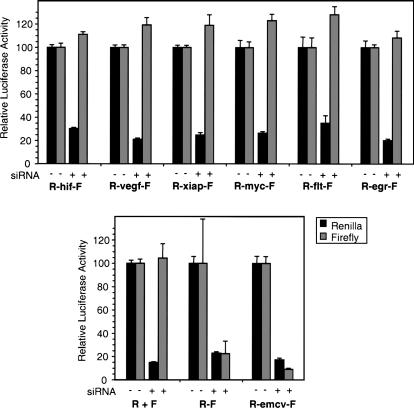

As a second test of the presence of monocistronic firefly luciferase transcripts in cells transfected with the dicistronic reporter, we used an approach devised by Lloyd and colleagues (Van Eden et al. 2004a), in which the Renilla region of the dicistronic transcript is targeted by RNA interference. The firefly activity would be reduced in proportion if it were derived from the same transcript, but remain unaffected if derived from cryptic monocistronic transcripts. In control experiments we found that cotransfection of siRNA targeting the Renilla luciferase coding region had no effect on the expression of firefly luciferase expressed from a monocistronic reporter (Fig. 3, lower panel). In cells transfected with the R-emcv-F dicistronic reporter plasmid, cotransfection with the Renilla siRNA caused a reduction in firefly luciferase activity comparable to the reduction in Renilla luciferase, indicating that both enzymes in these cells are translated from the same, dicistronic mRNA. In contrast, cotransfecting Renilla siRNA with dicistronic reporters containing either the HIF-1α, VEGF, c-myc, XIAP, VEGF-R1, or Egr-1 5′ UTRs resulted in each case in substantial reduction of Renilla luciferase activity without any reduction of firefly luciferase activity (Fig. 3, upper panel). This confirms that the firefly luciferase in these transfection experiments is produced predominantly from cryptic monocistronic transcripts.

FIGURE 3.

Knockdown of dicistronic transcripts by RNAi targeting the Renilla luciferase coding region does not reduce firefly luciferase expression from reporters containing cellular UTRs. The indicated plasmids were cotransfected with pCMV-SPORT-βgal, with or without 1 pmol of Renilla Luciferase siRNA mix as indicated. R + F indicates cotransfection of monocistronic Renilla and firefly reporters. Renilla and firefly luciferase activities were determined 24 h post-transfection, and data were normalized to β-galactosidase activity to control for any variations in transfection efficiency. The amount of each luciferase activity is shown as a percentage relative to the amount produced in the absence of Renilla siRNA. Data are shown as the mean (± SEM) of a total of five samples from two independent experiments.

IRES activity measured by RNA transfection

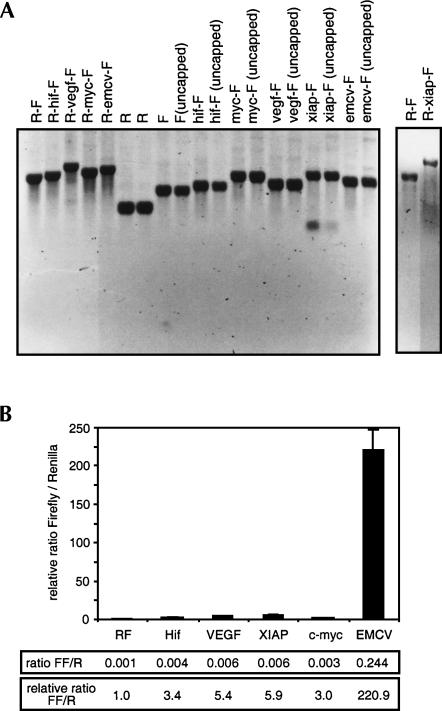

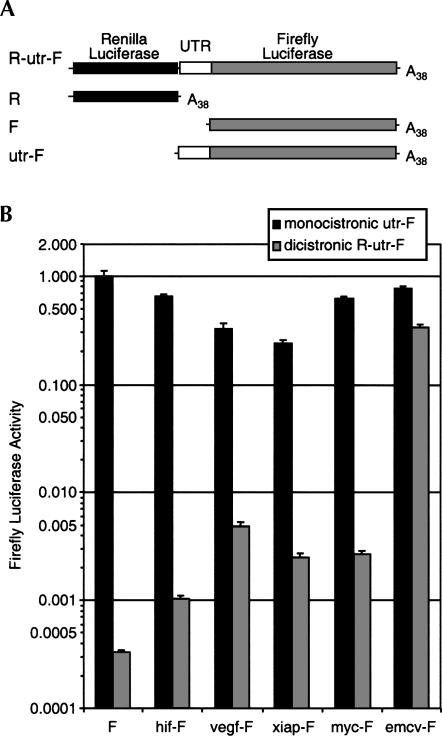

The experiments described above show that the dicistronic reporter gene does not give a reliable assay for IRES activity because most of the downstream luciferase activity is produced from monocistronic transcripts that result from activation of cryptic promoters. One way to eliminate any contribution from cryptic promoters is to transfect the cells with mRNA instead of plasmid DNA. Because bacteriophage RNA polymerases such as the SP6 and T7 RNA polymerases initiate transcription from a highly specific promoter sequence, mRNA transcribed in vitro using these enzymes is essentially devoid of any monocistronic downstream luciferase transcript. We inserted the dicistronic reporter constructs—R-hif-F, R-vegf-F, R-myc-F, R-xiap-F, R-emcv-F, and R-F—into the pSP65–20B vector, which contains the SP6 RNA polymerase promoter and an encoded 38-nt poly(A) tail. Capped polyadenylated mRNAs were transcribed in vitro (Fig. 4A) and transfected into HeLa cells. The resulting Renilla luciferase and firefly luciferase activities were measured 15 h after transfection (Fig. 4B). A small but measurable amount of firefly luciferase activity was produced from the R-F negative control mRNA, which has just a short linker sequence separating the two luciferase reading frames. Insertion of the HIF-1α, VEGF, c-myc, or XIAP 5′ UTRs resulted in a three- to sixfold increase in relative firefly luciferase activity over the negative control, whereas the EMCV IRES increased the relative firefly luciferase activity by 220-fold (Fig. 4). These data suggest that all the cellular 5′ UTRs tested have some IRES activity, although this activity is low in comparison to the EMCV IRES.

FIGURE 4.

Relative IRES activities determined by transfection of in vitro transcribed dicistronic mRNAs. (A) Denaturing gel electrophoresis of in vitro transcribed mRNAs. Two micrograms (2 μg) of each mRNA as indicated was electrophoresed on a denaturing formaldehyde agarose gel and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. Because a proportion (∼50%) of R-xiap-F in vitro transcripts terminate prematurely within the XIAP UTR, this mRNA was additionally purified by isolation of poly(A+) RNA on oligo d(T) magnetic beads, and 1 μg of the purified mRNA was electrophoresed on a denaturing formaldehyde agarose gel and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide in the panel on the right. (B) Capped, polyadenylated dicistronic mRNAs were transfected into HeLa cells, and Renilla and firefly luciferase activities were determined 15 h post-transfection. The ratios of firefly luciferase to Renilla luciferase are shown relative to the ratio for R-F, which was given a value of 1. Data are presented as the mean (± SEM) of triplicate samples from a minimum of three transfections.

IRES activity compared to cap-dependent initiation

To ascertain whether the relatively low level of IRES activity detected with the dicistronic mRNAs is at all comparable to the level of translation that could result from cap-initiated translation from these UTRs, we prepared monocistronic and dicistronic forms of firefly luciferase mRNA, with and without the various UTRs fused to the luciferase reading frame (Fig. 5A). Capped, polyadenylated mRNAs were synthesized in vitro and transfected into HeLa cells, along with a β-galactosidase reporter to normalize for any variation in transfection efficiency. The monocistronic firefly luciferase mRNAs containing the HIF-1α, c-myc, and EMCV UTRs gave rise to luciferase levels that were 62%–77% of what was produced from the control monocistronic luciferase mRNA, F, which has only a short, relatively unstructured UTR. This indicates that the GC-rich HIF-1α and c-myc UTRs are not particularly inhibitory to translation (Fig. 5B, black columns). The mRNAs containing the VEGF and XIAP 5′ UTRs produced only 24%–33% of the amount of firefly luciferase activity, consistent with these longer 5′ UTRs having a more inhibitory effect on translation.

FIGURE 5.

IRES-dependent translation from the cellular IRESs is weak compared to cap-initiated translation. (A) Schematic illustration showing the monocistronic and dicistronic mRNAs. (B) Comparison of the firefly activities produced from monocistronic vs. dicistronic mRNAs. Capped, polyadenylated monocistronic and dicistronic firefly luciferase mRNAs were prepared in vitro. For each transfection a constant molar amount of firefly and Renilla cistron was used. (For transfection with monocistronic mRNAs, this was an equimolar mixture of Renilla and firefly mRNAs, and each equal to the molar amount transcript used for transfection of dicistronic mRNA.) β-Galactosidase reporter was included in each transfection to normalize for any variations in transfection efficiency. The luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured at 15 h after transfection. Firefly luciferase activity is shown relative to F, the firefly luciferase mRNA with a short vector-derived 5′ UTR.

For each UTR, we next compared the level of firefly luciferase activity produced from the dicistronic mRNA to the activity produced from monocistronic mRNA containing that UTR. Luciferase expressed from the dicistronic mRNA would be produced by internal ribosome entry, whereas luciferase expressed from the monocistronic mRNA could either be initiated from the IRES or from the cap. The firefly luciferase activity expressed from the dicistronic mRNA containing the EMCV IRES (R-emcv-F) was about half that expressed from the monocistronic mRNA (emcv-F) (Fig. 5B). However, for mRNAs containing the HIF-1α, VEGF, c-myc, and XIAP UTRs, the activity produced from the dicistronic mRNAs was less than 2% of the activity produced from the corresponding monocistronic mRNA.

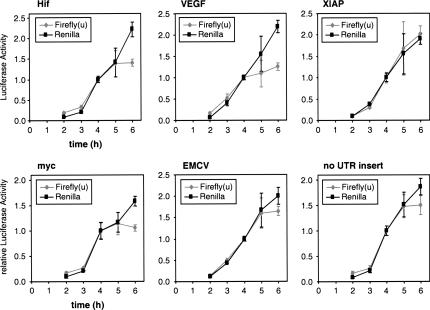

One possible reason for the low activity of the cellular IRESs when assayed in a dicistronic reporter is that the dicistronic context is not favorable for IRES activity, perhaps because the presence of the upstream Renilla luciferase coding region somehow interferes with IRES structure or function. To circumvent this possibility, we measured the IRES activity of the various UTRs in a monocistronic context, by comparing the luciferase activity produced from uncapped versus capped monocistronic RNAs (shown in Fig. 4A). Because the uncapped RNA may not be stable for 15 h after transfection, we first conducted a time course to determine a more appropriate time for harvest after transfection. We found that the luciferase activity from uncapped RNAs accumulated linearly for at least 4 h (Fig. 6). This linear increase in luciferase activity indicates that little RNA degradation occurs during the first 4 h following transfection and is consistent with previous reports that showed capped and uncapped RNA to be equally stable for at least 4 h in transfected cells (Wang and Kiledjian 2001; Van Eden et al. 2004b). We therefore selected 4 h post-transfection as an appropriate time to harvest the cells for luciferase measurement.

FIGURE 6.

Time course of luciferase activity in cells transfected with various uncapped firefly luciferase mRNAs. Uncapped monocistronic firefly luciferase mRNAs with the indicated 5′ UTRs were transcribed in vitro and cotransfected with capped monocistronic Renilla luciferase mRNA into HeLa cells. Luciferase activities were determined at the various times indicated and are expressed relative to the activity at 4 h. Data are shown as mean (± SEM) from a minimum of three transfections.

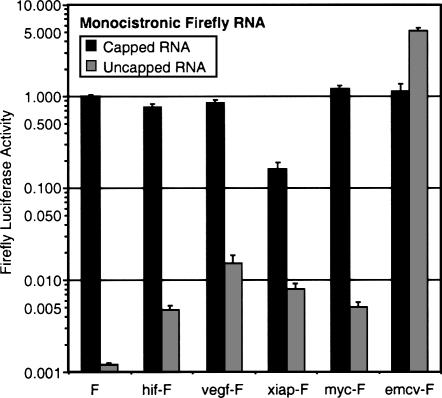

The luciferase activity in cells transfected with uncapped control luciferase RNA (without any additional 5′ UTR) was very low in comparison to that expressed from the capped form of the RNA (Fig. 7). Insertion of the EMCV 5′ UTR restored activity to the uncapped RNA, consistent with the known presence of an IRES in the EMCV 5′ UTR. Indeed the uncapped EMCV-luc RNA produced more luciferase than either the capped control or the capped EMCV-luc mRNAs. The cellular UTRs also increased the level of luciferase produced from uncapped mRNAs when compared to the uncapped control luciferase RNA, but the activity in each case was low compared to the activity from their respective capped mRNAs. For the XIAP-luciferase mRNA, the uncapped form produced less than 5% of the activity compared to capped mRNA. For all the other cellular UTRs the activity from the uncapped mRNA was <2% of the activity from the respective capped mRNA. These data indicate that the EMCV IRES functions efficiently when in a dicistronic or a monocistronic mRNA. In contrast, the cellular UTRs have very low IRES activity in this assay and the translation of transfected capped mRNAs is predominantly cap-dependent.

FIGURE 7.

The effect of various 5′ UTRs on translation of capped and uncapped monocistronic mRNAs. Capped and uncapped monocistronic firefly luciferase mRNAs with the indicated 5′ UTRs were transcribed in vitro and transfected into HeLa cells, along with an equimolar amount of control monocistronic Renilla luciferase mRNA for normalization of transfection efficiencies. Luciferase activities were determined 4 h post-transfection and are expressed relative to the activity from the capped F mRNA, which is the firefly luciferase mRNA with a short vector-derived 5′ UTR. Data are presented as the mean (± SEM) of triplicate samples from at least three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

The pR-F dicistronic reporter plasmid has been widely used to detect and measure IRES activity in cellular 5′ UTRs. We found by two separate criteria that the ratio of firefly luciferase to Renilla luciferase generated from transfecting cells with this plasmid did not reliably measure IRES activity. Firstly, the ratio was highly dependent on the composition of the elements within the SV40 promoter that drives transcription from the plasmid. Such an effect, seen with six different cellular UTR inserts, is highly indicative that the SV40 promoter influences each reporter separately, generating distinct mRNAs from which the two reporters are translated. Secondly, the selective reduction of Renilla luciferase activity by siRNA targeting the Renilla coding region, without reduction in firefly luciferase activity, verified that the majority of firefly luciferase was not translated from a dicistronic transcript. Our finding of cryptic activation in six out of six cellular UTRs tested adds to recent reports of the generation of cryptic transcripts from several individual cellular UTRs (Han and Zhang 2002; Sherrill et al. 2004; Van Eden et al. 2004a; Liu et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2005) and indicates this is a very common feature of the pR-F reporter.

It has been shown previously that a similar dicistronic reporter containing the XIAP 5′ UTR is prone to cryptic splicing, resulting in the generation of monocistronic luciferase transcripts (Van Eden et al. 2004a). We did not directly address whether cryptic splicing contributes to the production of firefly luciferase from the dicistronic reporter gene containing the XIAP 5′ UTR, but the marked effect on the ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase from changing the structure of the promoter indicates that cryptic promoter activity also makes a considerable contribution to the firefly luciferase activity. This was also the case with all the other cellular UTRs we tested. It appears that the same general feature that produces, or is suggestive of, IRES activity (GC richness, which promotes RNA secondary structure) also increases the potential for the DNA to act as a cryptic promoter (perhaps by increasing the occurrence of binding sites for transcription factors such as SP1, SP3, AP1, and NFKB, which bind to GC-rich sequences). Even very well authenticated IRESs, such as the IRES from hepatitis C virus, can give rise to considerable cryptic promoter activity (Dumas et al. 2003). The cryptic promoters may use heterogeneous start sites, as is sometimes the case with GC-rich promoters that do not contain a TATA box. This may contribute toward the lack of direct evidence of a cryptic transcript in previous assessments of the HIF-1α and c-myc IRESs (Stoneley et al. 1998; Lang et al. 2002). Indeed, the HIF-1α, c-myc, and VEGF 5′ UTRs all contain a sequence element, GCTCCC/G, that has been reported to commonly occur in multiple start site, TATA-less promoters (Ince and Scotto 1995).

We found that deletion of the SV40 proximal promoter region from dicistronic reporter genes containing cellular UTRs typically increased the expression of the downstream firefly luciferase if the enhancer region was left intact. Presumably when they both are present in the dicistronic plasmid, the SV40 proximal promoter can compete with a cryptic promoter for interaction with the SV40 enhancer element. Deletion of the SV40 proximal promoter would remove this competition, making the enhancer more available for activation of the cryptic promoter region. When both are present, the cryptic promoters in the cellular UTRs evidently compete quite successfully with the SV40 proximal promoter for the enhancer, because deletion of the enhancer affected expression of the downstream firefly luciferase more than it affected expression of the upstream Renilla luciferase.

Our results also suggest that deletion of the entire viral promoter region, which is sometimes used as a control for cryptic promoter activity, is not an adequate test for contribution from cryptic promoter activity. We found that removal of the entire SV40 promoter from the R-egr-F and R-vegfr1-F plasmids eliminates firefly luciferase activity, even though both are subject to cryptic promoter activation in the intact form of the plasmid. We also found a near-complete abrogation of firefly activity when the entire promoter was deleted from dicistronic reporter plasmids containing the HIF-1α and XIAP 5′ UTRs (data not shown). We suggest that rather than completely deleting the promoter, a better control for detecting cryptic monocistronic transcripts is the method developed by Lloyd and colleagues (Sherrill et al. 2004; Van Eden et al. 2004a; Byrd et al. 2005), using RNAi to knock down transcripts containing the upstream coding region. Finding that the downstream reporter is reduced in proportion to the upstream reporter can verify that both are translated from the same mRNA. In our experiments, however, this approach confirmed that for all six cellular UTRs tested (but not the EMCV positive control), most of the downstream reporter activity was translated from mRNA that did not contain the upstream Renilla luciferase reporter. Some studies of putative IRESs have used dicistronic reporters that contain the CMV promoter, rather than the SV40 promoter. We do not know whether the CMV promoter tends to activate cryptic promoters, but it would appear prudent to apply the RNAi test, because powerful enhancer elements are also present in the CMV promoter (Boshart et al. 1985).

Having found that transfection of the dicistronic reporter plasmids measured cryptic promoter activity more than it measured IRES activity, we used RNA transfection to measure the activity of the various putative IRESs. We found that dicistronic mRNAs containing the HIF-1α, VEGF, c-myc, and XIAP 5′ UTRs consistently and reproducibly produced more downstream firefly luciferase than the dicistronic control mRNA, which has only linker sequence between the two cistrons, but the level of activity from these putative IRESs was only 1%–2% of the activity produced from mRNA containing the EMCV IRES. The reporter activity produced from each cellular IRES was also <2% of the activity produced from capped monocistronic mRNAs containing these 5′ UTRs. Together these data suggest that the HIF-1α, VEGF, c-myc, and XIAP 5′ UTRs do support some degree of internal ribosome entry, but that the IRES activities when measured by transfecting the mRNA are very low. The very low activity of the c-myc IRES in RNA transfection experiments has been noted previously, prompting the suggestion that this IRES may need to transit the nucleus in order to become active (Stoneley et al. 2000b). We attempted to test this hypothesis by transfecting the dicistronic mRNAs using the AMAXA nucleofector. This electroporation device delivers a double pulse that is claimed by the manufacturer to allow the electroporated RNA or DNA to directly enter the nucleus. In transfection experiments using the nucleofector, we found that dicistronic mRNA containing the EMCV IRES produced high levels of firefly luciferase, but the relative firefly luciferase activities produced from dicistronic mRNAs containing the HIF-1α, VEGF, c-myc, and XIAP IRESs were no higher than was produced in cells transfected by the conventional cationic lipid method (data not shown). Attempts to confirm by fluorescence microscopy that the nucleofected RNA was entering the nucleus were inconclusive. In the absence of confirmation that the AMAXA nucleofector delivers the mRNA to the nucleus, we cannot make a firm conclusion regarding the effect of nuclear transit on IRES activity, apart from the observation that this is not a requirement for activity of the EMCV IRES. The low activity of cellular IRESs in RNA transfection experiments is not likely to be solely due to inaccessibility of the IRES within a large RNA, because low activity was found not just with dicistronic RNAs, where the IRESs were flanked by Renilla and firefly luciferase coding regions, but also when the IRESs were at the 5′ end of uncapped monocistronic RNAs. It remains possible the cellular IRESs failed to adopt an appropriate structure when synthesized in vitro, although the positive control EMCV IRES was functional, and so must have folded correctly.

HIF-1α, VEGF, c-myc, and XIAP have all been shown to have their translation rate maintained during one or more conditions of cellular stress that causes a reduction in overall protein synthesis. HIF-1α and VEGF mRNAs remain polysomal during hypoxia (Stein et al. 1998; Lang et al. 2002), consistent with the functional role of the protein as a hypoxia response factor. XIAP protein levels can increase in irradiated or serum-starved cells without increase in the amount of mRNA (Holcik et al. 1999). C-myc in particular was found to be translationally privileged in various circumstances. C-myc mRNA remains polysomal in poliovirus-infected cells (Johannes et al. 1999), and the c-myc 5′ UTR allows the translation of chimeric reporter genes to be maintained during apoptosis (Stoneley et al. 2000a), mitosis (Pyronnet et al. 2000), and genotoxic stress (Subkhankulova et al. 2001). Because IRES-mediated initiation avoids a requirement for eIF4E, it provides a logical mechanism for the privileged translation observed under these conditions. However, although we find that the 5′ UTRs of HIF-1α, VEGF, c-myc, and XIAP do have greater IRES activity than a negative control RNA segment, the amount of protein produced as a result of IRES activity in the RNA transfection experiments is low compared to the amount that is produced from cap-dependent translation. It is possible that the RNA transfection assay of IRES activity severely underestimates the true activity, but to date this is not supported by direct experimental evidence. This does not mean to say that these IRESs are now proven to be irrelevant, but we cannot reliably conclude that these IRESs are physiologically relevant until it is shown that the level of IRES activity is sufficient to compensate for a physiological reduction of cap-initiated translation. It also remains possible that the privileged expression of proteins such as HIF-1α, VEGF, c-myc, and XIAP during periods of general translational down-regulation could be due to special features of their 5′ UTRs that favor their translation during cellular stress, despite their translation being cap initiated. Indeed, a recent report has shown that translation of eIF4G can be mediated by a cap-dependent IRES when the bulk of translation is inactivated by poliovirus infection (Byrd et al. 2005). However, for many cellular mRNAs reported to contain an IRES, the conclusion has been based mainly on results from plasmid-based dicistronic reporters, and further investigation of these may be needed to reliably conclude they have sufficient IRES activity to support the cellular requirements in lieu of cap-initiated translation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

HeLa cells were cultivated in Dulbecco's modified eagle's medium (JRH Biosciences) containing 10% heat-inactivated defined bovine serum (HyClone), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 4 mM glutamine. Cells were kept at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Plasmid constructs

The plasmids pR-F, pR-hif-F, pR-vegf-F, and pR-myc-F have been described previously (Lang et al. 2002). To construct R-egr-F, HeLa cell genomic DNA was PCR amplified using primers GAATTCACTAGTCCGCAGAACTTGGGGAG and AAGCTTCCATGGCCTGGACGAGCAGGCTG, corresponding to the 270 nt at the 3′ end of the 5′ UTR. Amplified product of ∼300 bp was selected by gel electrophoresis, reamplified with the same primers, digested with NcoI and SpeI, and inserted into the pR-F plasmid digested with the same enzymes. To construct R-vegfr1-F, HeLa cell genomic DNA was PCR amplified using primers TGACGTCACCAGAAGGAGGT and GGTGTCCCAGTAGCTGACCA and the product reamplified with primers TGACGTCACCAGAAGGAGGT and CGACTAGTATCGAGGTCCGC. The resulting product was digested with NcoI and SpeI and inserted into the pR-F plasmid digested with the same enzymes. Plasmid pR-xiap-F was made by inserting the XIAP 5′ UTR (PCR-amplified from plasmid pbgal/hUTR/CAT [Holcik et al. 1999] with primers GGACTAGTCTGTTGTCCCAGTGTGA and CATGCCATGGCTTCTCTTGAAAATAGGACT) into SpeI and NcoI sites of pR-F. To create plasmid pR-emcv-F, the EMCV IRES (comprising 560 nt from the 3′ end of the EMCV 5′ UTR) was excised from plasmid MSCV-GFP (Leimig et al. 2002) as an EcoRI/NcoI fragment and inserted between the EcoRI and NcoI sites of pR-F.

To generate dicistronic plasmids without promoter (generically called pR-utr-FΔprom), the plasmids were digested with BglII and EcoRV and re-ligated. To remove the enhancer from pR-F, a BamHI site was inserted downstream of the SV40 polyadenylation region by site-directed mutagenesis and the resulting plasmid was digested with BamHI and re-ligated, creating pR-FΔenh. The various UTRs were then inserted between the Renilla and firefly coding regions as described above for generation of the pR-utr-FΔenh series of plasmids. To construct dicistronic plasmids with neither promoter nor enhancer (pR-utr-FΔpromΔenh), the pR-utr-FΔenh plasmids were digested with BglII and EcoRV and re-ligated.

Plasmids for in vitro transcription of dicistronic mRNA—pSP65-R-F, pSP65-R-hif-F, pSP65-R-vegf-F, pSP65-R-myc-F, and pSP65-R-xiap-F—were created by excising the region encompassing the dicistronic reporters from the pR-utr-F plasmids with EcoRV and XbaI and inserting this between the SmaI and XbaI sites of plasmid pSP65–20B (Munroe and Jacobson 1990), between the SP6 promoter and A38 tract. The pSP65–20B vector contains a unique HindIII site downstream of the poly(A) tract, allowing linearization of the template for in vitro transcription. Because the EMCV 5′ UTR contains an endogenous HindIII site, the plasmid pSP65-R-emcv-F was created as above but additionally had the oligo sequence AGCTAGGATCCCGGGCTGCAC inserted at the HindIII site adjacent to the A38 tract, thereby inserting a unique BsgI site that allows linearization of the plasmid immediately downstream of the A38. Plasmid pCMV-SPORT-βgal was obtained from Invitrogen.

In vitro transcription

pSP65 plasmids were linearized at the 3′ end of the poly(A) region using Hind III (or BsgI for pSP65-R-emcv-F). Capped transcripts were synthesized using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE SP6 kit (Ambion). Uncapped RNA was synthesized by 40 U SP6 RNA polymerase in the presence of 1 mM NTPs, 10 mM DTT, 50 U RNasin, 5 μg plasmid template, and Transcription Optimized Buffer (Promega) for 2 h at 37°C, and DNA was removed by digestion for 15 min with RQ1 DNaseI (Promega). All RNAs were purified using Qiagen RNeasy mini kits to remove unincorporated nucleotides and cap analog. An aliquot of each RNA was run on a denaturing formaldehyde agarose gel to check RNA quality (Fig. 3).

DNA and RNA transfection

For both RNA or DNA transfections, 1.5 × 105 cells were plated into 24-well plates 24 h prior to transfection. For DNA transfection, 1 μg of DNA was transfected using LipoFectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the protocol supplied. Cells were washed 6 h post-transfection and media replaced. Twenty-four hours following transfection, cell extracts were harvested using Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega). For RNA transfection, 0.55 pmol (500–700 ng) of RNA was transfected using TransMessenger reagent (Qiagen) as per the manufacturer's recommendations. Cell extracts were harvested using Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega). For cotransfection with siRNAs targeting the Renilla luciferase coding region, 200 ng of dicistronic reporter plasmid, 100 ng β-galactosidase reporter plasmid, plus 1 pmol Renilla Luciferase shortcut siRNA mix (New England Biolabs) were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer's recommendations.

Reporter assays

Firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase activities were measured as described previously (Lang et al. 2002). β-galactosidase activity was assayed using a β-galactosidase enzyme assay system (Promega) as recommended by the supplier.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Allan Jacobson for plasmid pSP65-20B, Martin Holcik for pβgal/hUTR/CAT, Yeesim Khew-Goodall for critical reading of the manuscript, and Thomas Preiss and all members of the Goodall laboratory for helpful discussion. This work was supported by grant S18/03 from The Cancer Council of South Australia and program grant no. 158067 from the National Health and Medical Research Council.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.2320506.

REFERENCES

- Akiri G., Nahari D., Finkelstein Y., Le S.Y., Elroy-Stein O., Levi B.Z. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression is mediated by internal initiation of translation and alternative initiation of transcription. Oncogene. 1998;17:227–236. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boshart M., Weber F., Jahn G., Dorsch-Hasler K., Fleckenstein B., Schaffner W. A very strong enhancer is located upstream of an immediate early gene of human cytomegalovirus. Cell. 1985;41:521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd M.P., Zamora M., Lloyd R.E. Generation of multiple isoforms of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4GI by use of alternate translation initiation codons. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:4499–4511. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4499-4511.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd M.P., Zamora M., Lloyd R.E. Translation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4GI (eIF4GI) proceeds from multiple mRNAs containing a novel cap-dependent internal ribosome entry site (IRES) that is active during poliovirus infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:18610–18622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414014200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas E., Staedel C., Colombat M., Reigadas S., Chabas S., Astier-Gin T., Cahour A., Litvak S., Ventura M. A promoter activity is present in the DNA sequence corresponding to the hepatitis C virus 5′ UTR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1275–1281. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B., Zhang J.T. Regulation of gene expression by internal ribosome entry sites or cryptic promoters: The eIF4G story. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:7372–7384. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7372-7384.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellen C.U., Sarnow P. Internal ribosome entry sites in eukaryotic mRNA molecules. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:1593–1612. doi: 10.1101/gad.891101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcik M., Lefebvre C., Yeh C., Chow T., Korneluk R.G. A new internal-ribosome-entry-site motif potentiates XIAP-mediated cytoprotection. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:190–192. doi: 10.1038/11109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huez I., Creancier L., Audigier S., Gensac M.C., Prats A.C., Prats H. Two independent internal ribosome entry sites are involved in translation initiation of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:6178–6190. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ince T.A., Scotto K.W. A conserved downstream element defines a new class of RNA polymerase II promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:30249–30252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang S.K., Krausslich H.G., Nicklin M.J., Duke G.M., Palmenberg A.C., Wimmer E. A segment of the 5′ nontranslated region of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA directs internal entry of ribosomes during in vitro translation. J. Virol. 1988;62:2636–2643. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2636-2643.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes G., Carter M.S., Eisen M.B., Brown P.O., Sarnow P. Identification of eukaryotic mRNAs that are translated at reduced cap binding complex eIF4F concentrations using a cDNA microarray. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999;96:13118–13123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M. New ways of initiating translation in eukaryotes? Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:1899–1907. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.6.1899-1907.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang K.J., Kappel A., Goodall G.J. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α mRNA contains an internal ribosome entry site that allows efficient translation during normoxia and hypoxia. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:1792–1801. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-02-0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leimig T., Mann L., Martin M.P., Bonten E., Persons D., Knowles J., Allay J.A., Cunningham J., Nienhuis A.W., Smeyne R., et al. Functional amelioration of murine galactosialidosis by genetically modified bone marrow hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 2002;99:3169–3178. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Dong Z., Han B., Yang Y., Liu Y., Zhang J.T. Regulation of expression by promoters versus internal ribosome entry site in the 5′-untranslated sequence of the human cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27kip1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3763–3771. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D.L., Dibbens J.A., Damert A., Risau W., Vadas M.A., Goodall G.J. The vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA contains an internal ribosome entry site. FEBS Lett. 1998;434:417–420. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munroe D., Jacobson A. mRNA poly(A) tail, a 3′ enhancer of translational initiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1990;10:3441–3455. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier J., Sonenberg N. Internal initiation of translation of eukaryotic mRNA directed by a sequence derived from poliovirus RNA. Nature. 1988;334:320–325. doi: 10.1038/334320a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyronnet S., Pradayrol L., Sonenberg N. A cell cycle-dependent internal ribosome entry site. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:607–616. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R., Agol V.I., Andino R., Bayard F., Cavener D.R., Chappell S.A., Chen J.J., Darlix J.L., Dasgupta A., Donze O., et al. New ways of initiating translation in eukaryotes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:8238–8246. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.23.8238-8246.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrill K.W., Byrd M.P., Van Eden M.E., Lloyd R.E. BCL-2 translation is mediated via internal ribosome entry during cell stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:29066–29074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402727200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein I., Itin A., Einat P., Skaliter R., Grossman Z., Keshet E. Translation of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA by internal ribosome entry: Implications for translation under hypoxia. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:3112–3119. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoneley M., Paulin F.E., Le Quesne J.P., Chappell S.A., Willis A.E. C-Myc 5′ untranslated region contains an internal ribosome entry segment. Oncogene. 1998;16:423–428. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoneley M., Chappell S.A., Jopling C.L., Dickens M., MacFarlane M., Willis A.E. c-Myc protein synthesis is initiated from the internal ribosome entry segment during apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000a;20:1162–1169. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1162-1169.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoneley M., Subkhankulova T., Le Quesne J.P., Coldwell M.J., Jopling C.L., Belsham G.J., Willis A.E. Analysis of the c-myc IRES; a potential role for cell-type specific trans-acting factors and the nuclear compartment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000b;28:687–694. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.3.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subkhankulova T., Mitchell S.A., Willis A.E. Internal ribosome entry segment-mediated initiation of c-Myc protein synthesis following genotoxic stress. Biochem. J. 2001;359:183–192. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiyama-Kohara K., Iizuka N., Kohara M., Nomoto A. Internal ribosome entry site within hepatitis C virus RNA. J. Virol. 1992;66:1476–1483. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1476-1483.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eden M.E., Byrd M.P., Sherrill K.W., Lloyd R.E. Demonstrating internal ribosome entry sites in eukaryotic mRNAs using stringent RNA test procedures. RNA. 2004a;10:720–730. doi: 10.1261/rna.5225204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eden M.E., Byrd M.P., Sherrill K.W., Lloyd R.E. Translation of cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 (c-IAP1) mRNA is IRES mediated and regulated during cell stress. RNA. 2004b;10:469–481. doi: 10.1261/rna.5156804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Kiledjian M. Functional link between the mammalian exosome and mRNA decapping. Cell. 2001;107:751–762. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00592-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Sarnow P., Siddiqui A. Translation of human hepatitis C virus RNA in cultured cells is mediated by an internal ribosome-binding mechanism. J. Virol. 1993;67:3338–3344. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3338-3344.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Weaver M., Magnuson N.S. Cryptic promoter activity in the DNA sequence corresponding to the pim-1 5′-UTR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2248–2258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]