Abstract

BACKGROUND We wanted to explore the conceptual representations of illness and experiences with care among women who have learned of an abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) smear result.

METHODS The study took place in 2 primary care, family practice clinics serving low-income, multiethnic patients in the Bronx, New York City. We conducted qualitative, semistructured telephone interviews with 17 patients who had recently learned of abnormal findings on a Pap smear. After a preliminary coding phase, the investigators identified 2 important outcomes: distress and dissatisfaction with care, and factors affecting these outcomes. A model was developed on a subset of the data, which was then tested on each transcript with an explicit search for disconfirming cases. A revised coding scheme conforming to the dimensions of the model was used to recode transcripts.

RESULTS Women reported complex, syncretic models of illness that included both biomedical and folk elements. Many concerns, especially nonbiomedical concerns, were not addressed in interactions with physicians. An important source of both distress and dissatisfaction with care was the women’s lack of understanding of the inherent ambiguity of Pap smear results. When perceived care needs, which included emotional support as well as information, were not met, distress and dissatisfaction were greatly increased.

CONCLUSION In this study, patients’ illness models and expectations of care were not routinely addressed in their conversations with physicians about abnormal Pap smear results. When physicians can take the time to review patients’ illness models carefully, distress and dissatisfaction with care can be reduced considerably.

Keywords: Patient satisfaction, attitude to health, illness beliefs, qualitative research, women’s health, Papanicolaou test

INTRODUCTION

Of the almost 50 million Papanicolaou (Pap) tests performed annually in the United States, nearly 5% will require further evaluation, most because of low-grade abnormalities.1 Studies report that many women, especially those in ethnic minority groups, have poor understanding of the meaning of their results.2–4 Many experience distress related to abnormal results.3

A few qualitative studies have explored women’s understanding of abnormal Pap smear results,5–9 though most focus on women referred for colposcopy. An Australian study of women undergoing treatment found that the women had difficulty understanding the concept of precancer.6 Tomaino-Brunner et al,5 studying African American and Hispanic women referred for colposcopy, found a pervasive lack of knowledge regarding the referral and procedure, but they did not explore women’s illness representations. Chavez et al10 used a mixed methodology to examine beliefs about cervical cancer risk factors among Anglo women, Latinas, and physicians in southern California. They found considerable discordance in beliefs among the 3 groups, noting that Latinas were more likely to emphasize nonnormative or immoral behavior, whereas physicians’ beliefs reflected the current biomedical model of cervical dysplasia.

In this study we used qualitative methods to explore the experiences of low-income, ethnic minority women who recently learned that their Pap smears showed low-grade cervical cytology. One goal of the study was to gain understanding of women’s conceptual models of illness and care. A second goal was to explore women’s experiences with care received at the time of learning of low-grade cytologic findings. We sought to understand how these conceptual models and experiences with care modified distress associated with Pap smear results, with the aim of identifying ways of improving communication and care for women with abnormal Pap smear findings.

METHODS

The study was approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Committee of Clinical Investigations. Participants provided informed consent.

Participants

Women with low-grade Pap smear abnormalities were recruited from 2 urban family practice clinics serving ethnically diverse, low-income patients. Eligible subjects had been recently notified of a Pap smear classified as atypical, atypical squamous cells of uncertain significance, or low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

Women received letters describing the study from their primary care providers. Those who did not return a postcard requesting not to be contacted were called and invited to participate. Between March and July 2001, telephone interviews lasting 30 to 45 minutes were conducted in English or Spanish by a bilingual research assistant. The interviewing process continued until it became evident that no new themes were emerging in the data, a point known as data saturation.

The Interview

The goal of the interview was to understand women’s experiences in the context of their models of illness and care. In one part of the interview, women were asked to generate narratives of their experiences of learning about abnormal results. We asked women to describe how they learned about their results, the actions they took or considered, and their emotional response to the situation. In a second part of the interview, we explored women’s conceptual models of illness. To this purpose we used a model from the health psychology literature, the Illness Representation Model (IRM),11,12 which has been widely used to investigate a variety of health conditions. The IRM describes several conceptual dimensions of illness, including concepts of cause, consequences, and management and treatment. The interviewer explored women’s illness models through questions derived from some of the dimensions of the IRM. To gain better understanding of women’s perceived needs for care, we asked them to describe ideal ways of informing women of abnormal Pap smear results.

Detailed verbatim notes were taken by the interviewer, who typed out transcripts immediately after the interview. Although the investigators had doubts about the use of telephone interviews, once the interviewer had completed one or two interviews, it became clear that she was able to establish excellent rapport.

Analysis

The analysis team included a psychologist (AK), a family physician (MDM), and a medical student interviewer (KR). The team underwent a reflexivity exercise13 designed to expose preconceptions and expectations regarding findings. One member of the team was concerned about the importance of women’s voices and stories coming through. Another member was convinced the data would show that physicians were doing a very bad job explaining results to women. The third member of the team thought (wrongly as it turned out!) that the Pap smear result issue would not be salient to women, and we would not get interesting data. Team members independently read transcripts and made interpretive notes.

The goal of qualitative analysis is often to determine what is at stake for informants in a particular research context. Finding out what is at stake grounds the analysis by establishing the outcome of importance. After an intensive reading of a subset of the data and the development of a preliminary coding scheme, we developed an interpretive, theoretical model for understanding important outcomes and their modifiers. The fit of the model to the data was assessed for each interview, with an explicit search for disconfirming cases. The coding system was refined to reflect key elements of the model and was used to code all transcripts.

RESULTS

The Sample

The characteristics of the study sample are displayed in Table 1 ▶. Of 61 letters sent to eligible participants, refusal cards were received from 8. The interviewer randomly selected names from the remaining list. Twenty-four women were contacted successfully by telephone. Two declined to participate. Of the remaining 22 consenting participants, the interviewer was able to complete 17 interviews during a 5-week period.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Sample (N = 17)

| Characteristic | Number |

| Mean age, y | 34 (range 19–56) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Latina | 10 |

| African American | 4 |

| Other | 3 |

| Language of Interview | |

| English | 13 |

| Spanish | 4 |

| Papanicolaou test results | |

| Atypia or ASCUS | 13 |

| LGSIL | 4 |

ASCUS = atypical squamous cells of uncertain significance; LGSIL = low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

The Model

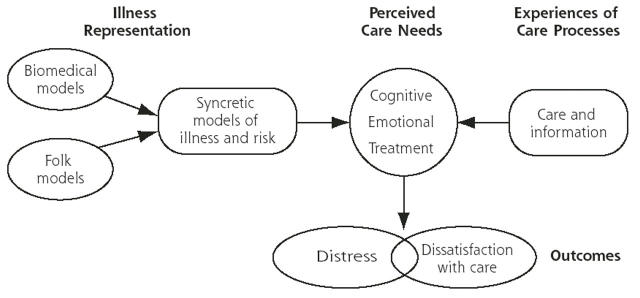

The theoretical model for the study is depicted by Figure 1 ▶. Intensive readings of this data set revealed 2 distinct, though related, outcomes of importance to participants: emotional distress and dissatisfaction with care. Perceived care needs result from patients’ illness representations, which are in turn shaped by biomedical and folk illness schemata. Perceived care needs vary from patient to patient and can include informational, emotional, and physical treatment needs. When the experience of care received fails to meet these needs, distress and dissatisfaction ensue.

Figure 1.

Women’s Experience of Abnormal Pap Smear Results: Processes and Outcomes.

Illness Representations

Participants described a wide range of explanations for abnormal results. Most had developed complex, syncretic illness models that incorporated both biomedical and folk elements. Strikingly, most women reported multiple explanatory factors and multiple potential consequences of abnormal Pap smear results. The Pap smear was often viewed as an all-purpose test that could detect a wide variety of conditions.

“A Pap smear is a checkup. It makes sure everything is normal down there. You know, you have intercourse, you are married, you want to make sure you don’t have anything. It keeps a woman healthy. Keeps her free from any sickness.”

Causes

What women believed caused the abnormal result is displayed in Table 2 ▶. Cancer was cited most often. Most patients believed that the test detected cancerous cells; only a few grasped the concept of precancer. Consequently, many believed they had cancer upon learning of an abnormal test result. Another common reported cause was infection. Women also mentioned various gynecologic problems, such as fibroids, ovarian cysts, and estrogen.

Table 2.

Participant Responses to the Question: “What Caused Your Abnormal Pap Smear Result?”

| Cause | Explanatory Narrative |

| Gynecologic problems | “I have a fibroid and they can become cancerous.” |

| Menopause or cysts | “Because one time I had a cyst. When I got the letter, I thought maybe she found the cyst again.” |

| “There is too much estrogen feeding into the uterus and these hormones can affect it to grow.” | |

| Sexual activity | “If you’re not protecting yourself. He’s ejaculating in you and it’s different—semen is different from what women have.” |

| “The fluid (semen) can carry venereal diseases.” | |

| Misbehavior | “I am a married woman. And I had this thing with this other man. Whatever I have, I have caused, I have brought it unto myself.” |

| “Sleeping around—doin’ it at a higher frequency. Bein’ more out there. Gettin’ exposed.” | |

| Medical error | “Possibly the tools they used were not sterilized. Maybe the Petri dish was infected.” |

| “Something not sterilized can obviously have bacteria. Then most likely it would go abnormal.” | |

| Miscellaneous | “Some of those, you know, on top of the McDonald’s hamburger ... poppy seeds. It could just show up on the Pap smear.” |

| “It could have been something I ate. ... I guess medication could affect it (Pap smear) or maybe it could have been something I had never eaten before ... it could’ve affected my system.” |

Sex and sexual misbehavior were frequently mentioned as causes of abnormal results. For example, semen present in the vagina was believed to cause abnormal results or create changes in the vagina. Some women believed having multiple sexual partners could cause an abnormal Pap smear finding. Other causes included diet and medical error.

As noted, women’s explanatory models were complex and various. Interestingly, the full picture of a woman’s explanatory model emerged slowly during the course of the interview. While conventional biomedical explanations of abnormal results were often provided at the outset, other explanations emerged only after systematic probing along the dimensions of the IRM. Women who reported concerns about sexuality and morality were especially likely to reserve these concerns for the latter part of the interview.

Distress

We asked women in detail about their emotional state related to abnormal Pap smear results. One of the most consistent findings in our study was a high degree of distress. Most women felt considerably upset at receiving the news of an abnormal Pap smear result. By the time of the interview, a few women felt better because they either had been reassured by their health providers, they had a normal result on follow-up examination, or (in 2 cases) they had decided to stop worrying because they were not experiencing symptoms.

“I can’t have cancer because I’m feeling okay. Cancer’s one of those diseases [where if you have it] you feel something. You don’t feel healthy.”

Sources of Distress

We identified several sources of distress stemming from women’s illness beliefs. Women who associated abnormal results with cancer and believed themselves to be at personal risk were frightened. By contrast, women who believed they were not at risk often had little reaction to the test results.

“I didn’t think anything about [the test result] because I don’t worry about cancer. I worry about diabetes! Cancer is not in my family but diabetes is.”

Women who associated abnormal results with sexual misbehavior experienced both fear and shame. There was an association between the immoral behavior (being “out there,” having many partners) and the moral consequences of this behavior, including the loss of fertility and feminine identity.

“I don’t want to think about it. If I have to take out my ... how do you say, womb, ... (sigh) if you have a husband and you don’t have a womb, you don’t have anything. You are not a woman. ... Sometimes I feel very depressed about it.”

Women experiencing symptoms they associated with abnormal results tended to be particularly distressed, reporting physical discomfort, fear, and frustration at the perceived lack of appropriate treatment.

“[My doctor] said to come back and do the Pap smear again in August. ... [But] ... itching and discharge—that is not normal. No woman can go on like that.”

A final important source of distress was uncertainty. Across the sample, many women were frustrated by the lack of a label for their condition. In the letters they received, women had usually been informed that their test results were “abnormal,” a term women found upsetting but unspecific.

“When I was speaking to my doctor, I was thinking and wanting to know to what degree is this abnormal?”

“You hear the word abnormal and you go crazy.”

Often women were informed in a letter that low-grade findings might or might not be clinically important. We found that women poorly understood the inherent ambiguity of low-grade findings. Ambiguity was often viewed as resulting from inadequate communication from the physician or a lack of knowledge by the physician. A couple of patients feared that information was being withheld. Many women believed that their tests should be repeated immediately and were highly distressed by having to wait.

“Repeating the test in 3 months! It got to me. I thought, Why so long? Why can’t they do it sooner? If it is cancer, it could spread.”

Experiences With Care

Discovery

The discovery experience is the first component of care a woman encounters when she is told of the abnormal cytology. Most women were informed of their results through a letter, though most of these women had a follow-up telephone call or in-person meeting with their physician. Because most women found the discovery of results a threatening and confusing experience, they were often dissatisfied with the letter method. Women complained that they did not understand what the letter meant or commonly did not understand what they were supposed to do.

“They sent me a second letter when it turned out abnormal again. [The letter] upset me. ... It didn’t even give me a possibility of what was going on. It didn’t make me feel like it was urgent. It just says come in and schedule this appointment. It doesn’t tell you what it is. It doesn’t tell you where it’s going.”

Dissatisfaction With Care

About one half of the women were dissatisfied with the care they received when they had an abnormal result. Systems issues were a major cause of complaint. Several described long waits for follow-up appointments, lost results, difficulty making telephone contact, or rude, unprofessional staff. Women were more reluctant to complain about their physicians than about systems problems. When asked at outset whether they were satisfied with their physicians’ care, most women said yes. As the interviews proceeded, however, it became clear that many women’s physicians had not addressed important concerns. In particular, we found that although many women discussed their fears of cancer with their providers, other issues, such as guilt about sexual misbehavior, or concerns related to folk beliefs, such as diet or gynecologic problems, had not been addressed.

Women who were most dissatisfied with care worried that information or care had been withheld.

“When you say, ‘Oh, we don’t know,’ that’s not helping anyone. When you say, ‘You have to see another doctor,’ that’s no way of making a person feel comfortable.”

For most women the most frustrating aspect of care was their uncertainty associated with the ambiguity of Pap smear results. When the physician tried to reassure the patient by saying, “It’s nothing,” or “don’t worry,” patients were not reassured. They thought that the physician was implying that it was not necessary to get further care. Some women worried that their physicians were too incompetent to make a diagnosis:

“I need a second opinion. ... A specialist doctor could see me and say, ‘This is what you have.’ Oh God, that would bring me so much relief.”

Women who believed they were at serious risk or who had troubling symptoms they associated with abnormal results were angry and frightened at what they perceived as a lack of care.

“She just kept saying, ‘It’s really nothing.’ I mean, how was I supposed to feel? She says something is abnormal. She says I need to come in and get a more complicated procedure, ... but she does not tell me what I have.”

Experiences With Physicians

We talked with women in some detail about their interactions with physicians when learning about Pap smear results. Their experiences suggested that physicians varied widely in the amount of time and effort they put into these interactions and the amount of concern they conveyed. From what our participants said, it appeared that some physicians viewed the test result conversation as an occasion to convey information. By contrast, most women saw this conversation as an opportunity to receive needed care, which included information but had other components, including emotional support and, in some cases, actual medical treatment.

Perceived Care Needs

We found that women wanted a response from their physicians that was caring, egalitarian, and tailored to their individual needs. The theme of individualized care, a construct we labeled “person care,” was pervasive. Most women wanted to discuss results in a face-to-face encounter.

“It is just the professional thing to do, to tell them in person. You need to be there, to see them, to see if they can handle it. You have to watch their face and try to communicate to them [in a way] they understand.”

They wanted the physician to take the time to explain things thoroughly. Asking questions and initiating a dialogue were viewed as particularly important.

“I definitely wouldn’t just say, ‘Here are your results and they are bad.’ I would ask you questions about Pap smears. Then I would ask how you would feel about having an abnormal Pap smear. We would work around the patient and work with the patient. Not everyone can take it, you know—bad news about their health.”

Many participants emphasized the idea that each woman is different and that physicians should tailor their communications to meet each woman’s care and information needs.

“I would ask them some questions, like, ‘Why do we do Pap smears?’ Just to see what are their expectations. Based on their responses to my questions, I would take it from there. You cannot give everyone the same speech. You have to know your patients.”

Using the Model to Understand Outcomes

Distress and dissatisfaction with care were shaped, first of all, by women’s illness representations. When a woman’s own conception of the cause and consequences of the abnormal cytology suggested a high level of risk and danger, she was more likely to be upset. Care from the provider that met a woman’s care needs relieved her distress; when she could not obtain this care, distress was unresolved or exacerbated.

We have described several barriers to receiving this care, including systems problems and occasionally inattentive physicians. Frequently clinicians failed to realize that women had unarticulated care and informational needs, often driven by illness representations very different from those of physicians. Most women described mixed illness models that included a variety of causes and consequences of abnormal results. Although cancer fears were often raised during the interview with the provider, concerns about sexual behavior usually were not.

In our search for disconfirming cases that did not fit the model, we found a few women in the sample who reported inadequate care but were not distressed. For several of these women, their own illness models led them to believe that risk and danger were low. In another case, a woman who had received inadequate “uncaring” care from a physician resorted to a folk healer. This healer gave her supportive “person care” and a folk treatment designed especially for her: a special tea intended to dissolve uterine cysts. This woman was highly satisfied with her care and attributed her normal Pap smear result on follow-up to this folk treatment. In a few other cases, women achieved composure by using other information sources, such as consulting others or searching the Internet.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies examining women’s beliefs and experiences related to Pap smear results and cervical cancer have found that many women, especially women belonging to an ethnic minority, report illness representations of cervical cancer that differ markedly from current biomedical models10 and have a poor understanding of the meaning of abnormal results.2–4 Studies have also shown that many women experience considerable distress in learning of abnormal Pap smear results.3 The goal of the present study was to examine the relation between women’s illness representations and their conceptual models of appropriate care, as well as to gain an understanding of the ways in which illness representations and care models modify the distress women experience when they are told they have abnormal Pap smear result.

In our sample of low-income Hispanic and African American women attending a primary care practice, we found, as in other studies,2–6,10 widespread misunderstanding of cervical cancer and of the purpose and meaning of the Pap test in addition to widespread distress. As expected, we found that illness representations of cervical cancer or illness associated with abnormal Pap smear results shaped women’s needs for care. When women’s illness representations suggested considerable threat, and when the care received did not address this threat, women’s distress was greatly increased.

Though our study used a nonrepresentative sample and was designed to generate, rather than test, hypotheses, the results suggest some important areas of concern to health care providers who care for women with abnormal cytology. We found that, in particular, the concept of ambiguity in the Pap smear result is especially difficult for providers to convey effectively. Well-meaning clinicians may offer reassurance that is misinterpreted. When physicians say, “Don’t worry about it,” women often interpret this message as deliberate vagueness. When physicians say, “We don’t know what this means,” women may wonder whether they need a second opinion. Thus, it might be particularly important to help women understand the inherent ambiguity of Pap smear results. It might be helpful to compare the Pap test with other medical tests and procedures that more clearly indicate the presence of disease and to explain why the recommendation to wait and repeat the test is appropriate care.

A common theme in our participants’ reports was the idea that the physician had simply not taken enough time or provided sufficient explanations in the discussion about the Pap smear results. Women’s concepts of ideal care during a visit for a Pap test emphasized mutuality and exchange. Accordingly, during the encounter, it might be helpful to review and exchange explanatory models with the patient.14 Our data suggest that in the case of Pap smear results and illness related to abnormal findings, explanatory models are complex and multilayered. Many women feel shame and guilt, as well as fear, but they may be unwilling to acknowledge these feelings during a brief or one-sided interaction. Thus, during a short encounter only those issues easiest to access may be discussed, leaving more troubling concerns unaddressed. Addressing such concerns could relieve distress and increase satisfaction with care.

The results of the study suggest the hypothesis that there might be differences in the way that physicians and patients conceptualize the purpose of the follow-up office visit. It is possible that some physicians view the office visit for a Pap test as limited to providing information, whereas women see it as an opportunity for physicians to provide care. Future research might usefully examine physicians’ concepts and strategies regarding the office visit for a Pap test and examine their relationship to patients’ distress and dissatisfaction. In the meantime, however, physicians might want to examine their own assumptions about the meaning and purpose of the Pap test and talk with patients more directly about their expectations of care.

Conflicts of interest: none reported

REFERENCES

- 1.Brotzman GL, Apgar BS. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: current management options. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKee MD, Lurio J, Marantz P, Burton W, Mulvihill M. Barriers to follow-up of abnormal Papanicolaou smears in an urban community health center. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lerman C, Hanjani P, Caputo C, et al. Telephone counseling improves adherence to colposcopy among lower-income minority women. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:330–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKee MD, Schechter C, Burton W, Mulvihill M. Predictors of follow-up of atypical and ASCUS papanicolaou tests in a high-risk population. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomaino-Brunner C, Freda MC, Runowicz CD. “I hope I don’t have cancer”: colposcopy and minority women. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1996; 23:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kavanagh AM, Broom DH. Women’s understanding of abnormal cervical smear test results: a qualitative interview study. BMJ. 1997;314: 1388–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennetts A, Irwig L, Oldenburg B, et al. PEAPS-Q: a questionnaire to measure the psychosocial effects of having an abnormal pap smear. Psychosocial Effects of Abnormal Pap Smears Questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48:1235–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunt LM, de Voogd KB, Akana LL, Browner CH. Abnormal Pap screening among Mexican-American women: impediments to receiving and reporting follow-up care. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998;25:1743–1749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahn JA, Chiou V, Allen JD, Goodman E, Perlman SE, Emans SJ. Beliefs about Papanicolaou smears and compliance with Papanicolaou smear follow-up in adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1046–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chavez LR, McMullin JM, Mishra SI, Hubbell FA. Beliefs matter: cultural beliefs and the use of cervical cancer-screening tests. Am Anthropol. 2001; 103:1114–1129. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leventhal H, Diefenbach M, Leventhal EA. Illness cognition: using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cognit Ther Res. 1992;16:143–163. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. The common sense representation of illness danger. In Rachman S, ed. Contribution to Medical Psychology. Vol 2. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1980:7–30.

- 13.Barry CA, Britten N, Barber N, Bradley C, Stevenson F. Using reflexivity to optimize teamwork in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 1999;9:26–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleinman A. The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing, and the Human Condition. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1988.