Abstract

BACKGROUND Despite recent attention given to medical errors, little is known about the kinds and importance of medical errors in primary care. The principal aims of this study were to develop patient-focused typologies of medical errors and harms in primary care settings and to discern which medical errors and harms seem to be the most important.

METHODS Thirty-eight in-depth anonymous interviews of adults from rural, suburban, and urban locales in Virginia and Ohio were conducted to solicit stories of preventable problems with primary health care that led to physical or psychological harm. Transcriptions were analyzed to identify, name, and organize the stories of errors and harms.

RESULTS The 38 narratives described 221 problematic incidents that predominantly involved breakdowns in the clinician-patient relationship (n = 82, 37%) and access to clinicians (n = 63, 29%). There were several reports of perceived racism. The incidents were linked to 170 reported harms, 70% of which were psychological, including anger, frustration, belittlement, and loss of relationship and trust in one’s clinician. Physical harms accounted for 23% of the total and included pain, bruising, worsening medical condition, and adverse drug reactions.

DISCUSSION The errors reported by interviewed patients suggest that breakdowns in access to and relationships with clinicians may be more prominent medical errors than are technical errors in diagnosis and treatment. Patients were more likely to report being harmed psychologically and emotionally, suggesting that the current preoccupation of the patient safety movement with adverse drug events and surgical mishaps could overlook other patient priorities.

Keywords: Medical errors; harms; physician-patient relations; patient perspective; qualitative research; patient safety; quality assurance, health care; patient-centered care

INTRODUCTION

The report by the Institute of Medicine To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System 1 focused public attention on the problem of medical error. It also stimulated policy makers to devote new resources to characterize and prevent medical errors across the spectrum of health care. Much of the effort to date focuses on improving patient safety in hospitals, an appropriate priority given the suggested incidence of errors in inpatient settings,2– 4 the resulting anxiety engendered in the public sector,5 and the opportunities for system redesign that can reduce the risk for errors and harms.6 Yet most medical care occurs in ambulatory settings provided by primary care clinicians.7, 8

Published information about medical error in ambulatory primary care settings is limited.9– 13 It focuses on errors in diagnosis, treatment, and the delivery of preventive services and suggests that a cascade of information transfer problems is the proximal cause for many of these failures.14 Although important, these studies have serious limitations, including varied definitions of error, reliance upon physician reports and perspectives, inconsistent taxonomies of errors and harms, and an absence of the causal analyses advocated by human factors experts.15

Based on existing data, the prevailing perception is that medical errors endanger patients primarily through adverse drug events and surgical mishaps. Whether such errors pose the predominant threat to patients is unclear, however, because of the paucity of good epidemiological research. A fundamental source of uncertainty is whether the operational definitions of error used in patient safety studies and error surveillance systems are designed to capture the kinds of errors and harms that matter most to patients. The classic hospital-based studies of medical errors2– 4 dealt with injuries that prolonged the hospital stay and produced disability at the time of discharge. The scope of harm experienced by patients is clearly broader, however, and it almost certainly differs between inpatient and outpatient settings.

Relatively little work has been done to understand the patient’s experience of medical errors in either setting. Large national and regional fixed-response surveys of the general population have been conducted.16– 19 Such surveys in the United States have documented that medical errors and dissatisfaction with care are common experiences and that public perceptions about errors appear to differ from those of clinicians, but the surveys leave largely unanswered the specific nature of the errors and associated harms that consumers experience. Even less is known about the specific patient experience in primary care settings. This lack of knowledge hinders efforts to design, implement, and evaluate patient-centered care.

We report a qualitative study of primary care patients based on in-depth interviews to understand their experience of medical errors. Our specific aims were to develop patient-focused typologies of medical errors and associated injuries (or harms) in primary care settings; to understand from patients’ perspectives which of these errors and injuries are most in need of correction; and to provide a basis for other research that will investigate error epidemiology, causes, and prevention. Additional aims, which we do not report on here in any detail, were to compare and contrast the patient’s descriptions with reports of errors solicited from physicians and to construct simulations or guide observation of actual practice, with a goal of correcting system problems that predispose to the most important errors.

METHODS

Trained telephone recruiters used random-digit dialing to solicit adult respondents who received their care from general internists or family physicians, or whose children received their care from pediatricians or family physicians, in rural, urban, and suburban communities in Virginia and Ohio. Between 10 and 20 completed calls were required to recruit 1 respondent. Most solicitation calls were answered by female adults. To obtain our goal of one-third male respondents, we sometimes obtained support for the study from a female adult and asked her to solicit involvement from a male adult household member. Respondents were told they would contribute to a federally funded study of problems in primary health care. They were offered $50 to participate in the interviews, which lasted approximately 45 minutes and were conducted at the individual’s home or another mutually convenient location. Three African American women were trained as interviewers and were selected for their ability to relate well to persons from diverse socioeconomic groups. We reasoned that a male or white interviewer might inhibit the spoken communication of some respondents. The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed, and personally identifiable information was deleted.

The interviewers used an interview guide to solicit narratives of preventable incidents in primary care that resulted in a perceived harm. This framework was chosen to fit the following broad definition of error (favored by the investigators for this exploratory study): all forms of improper, delayed, or omitted care that unnecessarily injures patients by either worsening health outcomes or causing physical or emotional distress. Incidents that were not preventable, but were believed by our respondents to be inevitable consequences of care, were not coded as errors. Respondents were asked to describe both the incident and the harm with as many additional stories as they could recall. A cue card listing steps in primary care (telephoning the office, checking in for an appointment, being brought back to the examination room, etc) prompted respondents to remember a range of incidents.

When all individual incidents were reported, the respondent was asked to group them according to which were the most and least disturbing. The interview also included questions regarding the duration of the relationship with the clinician and the demographic characteristics of the clinician and the respondent. Based on analysis of the initial interviews, subsequent respondents were asked to characterize their relationship with the clinician and probed for any perceived discrimination based upon race, age, sex, or ability to pay. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Office of Human Subjects Protection of Virginia Commonwealth University, and all respondents signed informed consent forms. A detailed exposition of the research proposal to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, including the interview guide and cue card used for the study, has recently been published.20

The two principal investigators (AJK and SHW) independently performed the initial analysis of each interview, using an editing style of analysis.21 In this method, one acknowledges previous constructs and assumptions but explicitly checks them against the data, making necessary modifications as the investigation proceeds. The analysis was concurrent with data acquisition22 and created cumulative and prioritized lists of medical errors and harms. The investigators also looked for possible linkages between the themes of the stories and respondents’ characteristics (eg, sex, race, occupation) or clinician characteristics (eg, specialty, sex, race).

A 5-member consulting team with expertise in qualitative research design, medical psychology, medical sociology, critical theory, and error analysis provided ongoing critique of the quality of the coding, the taxonomy construct, and the linkage to existing knowledge about patient experiences of medical error. Ecological validity (explicit and implicit norms and understanding shared by members of a community)23 and authenticity (incorporating notions of fairness and a raised level of awareness)24 were promoted by sharing the analysis with 3 reactor panels (focus groups) of 6 to 10 patients each, recruited from urban, suburban, and rural communities in the 2 states.

With input from reactor panels and consultants, and with an eye toward linkage with the developing literature on medical errors, we derived a taxonomy of patient-reported errors organized around 5 domains: access breakdown (desired care blocked or delayed), communication breakdown (failed transfer of information), relationship breakdown (deficiencies in patient-centered care), technical error (slips, lapses, or violations), and inefficiency (needless waste of resources). Although the interview guide was designed to make the harm associated with every incident explicit, it was not always possible to discern explicit harm from the narratives, and the investigators chose not to infer harms when not stated.

RESULTS

Forty-one individuals agreed to an interview, and 40 interviews were completed. Two interviews (African American respondents from urban areas in Ohio) were unusable because of technical audiotape problems. Of the 38 usable interviews, 11 were from rural, 11 from suburban, and 3 from urban Virginia communities; the Ohio interviews occurred in 7 urban and 6 suburban settings. Twenty-nine respondents were female, and 29 were African American. The remaining respondents were white. Ages ranged from 21 to 77 years (median 38 years), and socioeconomic stratification (based on years of education, where stated) put 18 respondents in an upper class (more than 12 years’ education), 13 in a middle class (9 to 12 years’ education), and 5 in a lower class (fewer than 9 years’ education).

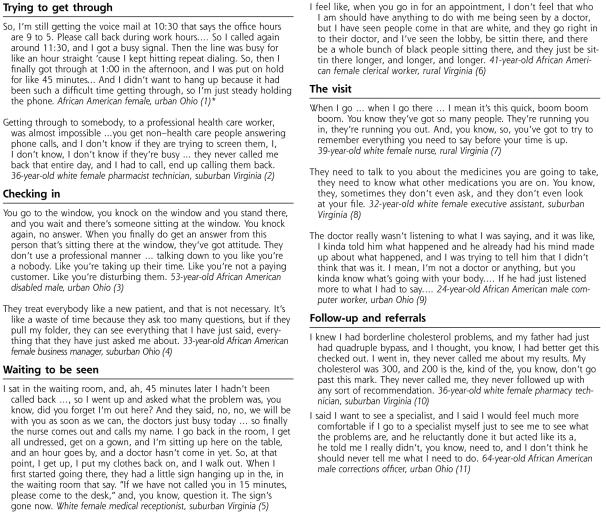

The 38 narratives described 221 problematic incidents, most of which patients linked to specific harms. The incidents fell within 70 fourth-order categories (ie, fourth layer of the taxonomy; 46 third-order categories are shown in Table 1 ▶), including errors of omission and commission, and occurred in all phases of primary care. Figure 1 ▶ provides illustrative excerpts, organized in the order of the primary care experience, to portray some of the most common and most troubling problems. (A larger set of selected quotes is available in Appendix 1, which is online only as supplemental data at http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/2/4/333/DC1.)

Table 1.

Unique Events Associated With Preventable Harms (N = 221), by Taxonomy Order

| Number of Unique Reports | |||

| Unique Events | 1st | 2nd | 3rd |

| 1. Access breakdown | 63 | ||

| 1.1. Difficulty initiating contact with office by telephone | 10 | ||

| 1.2. Excessive delay in obtaining appointment with clinician | 10 | ||

| 1.3. Excessive delay in obtaining referral to specialist | 1 | ||

| 1.4. Excessive delay in / no return of telephone call | 7 | ||

| 1.5. Excessive office waiting time | 17 | ||

| 1.6. Service not covered | 11 | ||

| 1.6.1. Medications not covered | 2 | ||

| 1.6.2. Family member excluded from practice | 1 | ||

| 1.6.3. Specialty services limited | 8 | ||

| 1.7. Service not available | 7 | ||

| 1.7.1. Lack of telephone care | 4 | ||

| 1.7.2. Lack of acute care | 2 | ||

| 1.7.3. Lack of evaluation before referral | 1 | ||

| 2. Communication breakdown | 17 | ||

| 2.1. Within office | 8 | ||

| 2.1.1. Insurance information not recorded | 1 | ||

| 2.1.2. Insurance information not updated | 1 | ||

| 2.1.3. Payment not posted | 1 | ||

| 2.1.4. Appointment improperly scheduled | 3 | ||

| 2.1.5. Wrong chart used for patient | 2 | ||

| 2.2. Between office and outside entity other than patient | 9 | ||

| 2.2.1. Referrals not done | 4 | ||

| 2.2.2. Improper coding of service | 1 | ||

| 2.2.3. Medication refill not called to pharmacy | 2 | ||

| 2.2.4. Records not transferred to requesting clinician | 2 | ||

| 3. Relationship breakdown | 82 | ||

| 3.1. Inadequate time with clinician | 9 | ||

| 3.2. Intermediary imposed on communication with clinician | 6 | ||

| 3.3. Care by other than usual clinician | 4 | ||

| 3.4. Disrespect or insensitivity | 63 | ||

| 3.4.1. Evident in interpersonal communication | 38 | ||

| 3.4.2. Evident in patient flow in office | 20 | ||

| 3.4.3. Evident in office environment | 5 | ||

| 4. Technical error | 54 | ||

| 4.1. Deficiency in history | 4 | ||

| 4.1.1. Incomplete history of present illness | 2 | ||

| 4.1.2. Incomplete history of medications | 1 | ||

| 4.1.3. Incomplete past history | 1 | ||

| 4.2. Deficiency in physical examination | 1 | ||

| 4.2.1. Incomplete physical examination | 1 | ||

| 4.3. Deficiency in investigations | 1 | ||

| 4.3.1. Artifact introduced in x-ray | 1 | ||

| 4.4. Deficiency in diagnosis | 11 | ||

| 4.4.1. Failure to appreciate severity/acuity of problem | 1 | ||

| 4.4.2. Wrong diagnosis | 4 | ||

| 4.4.3. Dismissing selected symptoms | 2 | ||

| 4.4.3. Perceived failure to make any diagnosis | 4 | ||

| 4.5. Deficiency in treatment and follow up | 35 | ||

| 4.5.1. Poor injection technique | 1 | ||

| 4.5.2. Results of investigations not shared with patient | 6 | ||

| 4.5.3. Inadequate patient education reprocedure, diagnosis or treatment | 18 | ||

| 4.5.4. Premature recommendation for hysterectomy | 1 | ||

| 4.5.5. Perceived polypharmacy | 1 | ||

| 4.5.6. Wrong medication dose | 2 | ||

| 4.5.7. No treatment for pain | 2 | ||

| 4.5.8. Inadequate follow up care | 4 | ||

| 4.6. Deficiency in business practice | 2 | ||

| 4.6.1. Requiring patient to pay before insurance company | 1 | ||

| 4.6.2. Balance billing by participating clinician | 1 | ||

| 5. Inefficiency of care | 5 | ||

| 5.1. Excessive data elements for registration | 1 | ||

| 5.2. Duplicative registration | 2 | ||

| 5.3. Unnecessary office visit | 2 | ||

Note: taxonomy is ordered from general to specific. Coding actually went to a fourth order of specificity; 3 orders are shown.

Figure 1.

Problems throughout the process of care.

* Typology codes:

- Access breakdown, difficulty contacting office, involving telephone system, telephone not answered, and excessive time on hold.

- Relationship breakdown, intermediary imposed on communication with clinician; and access breakdown, no return of telephone call.

- Relationship breakdown, disrespect or insensitivity, evident in interpersonal communication, rude behavior.

- Inefficiency of care, duplicative registration.

- Access breakdown, excessive office waiting time.

- Relationship breakdown, disrespect or insensitivity, evident in patient flow in the office, prioritizing patients based on race.

- Relationship breakdown, inadequate time with provider.

- Technical error, deficiency in history, incomplete history of medications.

- Relationship breakdown, disrespect or insensitivity, evident in interpersonal communication, patient advice ignored.

- Technical error, deficiency in treatment or follow-up, results of investigations not shared with patient.

- Relationship breakdown, disrespect or insensitivity, evident in interpersonal communication, patient preferences not respected.

The most common incidents involved breakdowns in the clinician-patient relationship (n = 82, 37%) and in access to clinicians (n = 63, 29%). Patients’ descriptions of breakdowns in the clinician-patient relationship were dominated by stories of disrespect or insensitivity, which accounted for 63 (77%) of the 82 incidents. Three kinds of problems accounted for 58% of the reported breakdowns in access (n = 63): difficulty in contacting the office (n = 10, 16%), delays in obtaining appointments (n = 10, 16%), and excessive office waiting times (n = 17, 27%). Technical errors such as misdiagnosis or adverse drug events were reported less frequently (n = 54, 24%) than were relationship and access breakdowns.

The incidents involved 170 reported harms, which fell into 40 categories (Table 2 ▶). Fully 119 (70%) of the 170 harms were psychological. Within this category patients were most likely to report anger (n = 31, 26%), frustration (n = 17, 14%), belittlement (n = 15, 13%), and loss of relationship with and trust in their clinician (n = 18, 15%). Pain and avoidable personal expense were the most commonly mentioned physical and economic harms, respectively.

Table 2.

Preventable Harms (N = 170) Reported by Respondents, by Number of Unique Instances

| Harm | Number |

| Psychological | 119 |

| Anger and related emotions | |

| Anger | 31 |

| Upset | 8 |

| Irritated | 4 |

| Frustrated | 17 |

| Personal worth | |

| Belittled | 15 |

| Sense of violation | 3 |

| Sense of betrayal | 1 |

| Relationship effects | |

| Diminished trust in clinician | 11 |

| Diminished relationship with clinician | 7 |

| Anxiety about health | 10 |

| Related to opportunity cost | |

| Wasted time | 6 |

| Anxiety about other responsibilities | 2 |

| Anxiety about bills | 2 |

| Forget important issue | |

| Other emotions | |

| Disappointed | 1 |

| Confused | 1 |

| Mood swing | 1 |

| Physical | 39 |

| Pain | |

| Not otherwise specified | 12 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 |

| Low back pain | 1 |

| Bruising | 4 |

| Related to medication effects | |

| Hypoglycemia | 2 |

| Somnolence | 1 |

| Drug interactions | 1 |

| Worsening problem | |

| Asthma | 3 |

| Hypertension | 1 |

| Cellulitis | 1 |

| Flank abscess | 1 |

| Uterine bleeding | 1 |

| Undertreated, untreated conditions | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1 |

| Diabetes | 1 |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | 1 |

| Other | |

| Weakness | 2 |

| “Sick” | 2 |

| Dizziness | 1 |

| Fever | 1 |

| Economic, other | 12 |

| Avoidable personal medical expense | 9 |

| Threat to credit rating | 1 |

| Lost work time, pay | 1 |

| End of sports career | 1 |

When asked toward the end of the interview to rank the incidents in terms of importance, most respondents emphasized technical failures of misdiagnosis, failure to disclose test results, and inadequate patient education; relationship breakdowns involving rude staff, disregard for patient concerns, and racial bias; and access breakdowns created by long waits for appointments.

The sample size and the qualitative coding of the data do not lend themselves to a statistical analysis of associations. Careful readings of the narratives, however, did not reveal any apparent patterns with respect to the sex or specialty of the clinician, duration of relationship, community type, state, form of health insurance, or the age, sex, and imputed socioeconomic status of the patient. The only obvious association with any characteristic was with respect to stories of apparent racism, which were heard only from African American respondents and which were found in stories from rural, suburban, and urban communities in both Virginia and Ohio.

Our reactor panels—the groups of people with whom we shared interview excerpts linked to our tentative coding scheme—validated our labels for the errors and told us that both physical morbidity and serious psychological harms were very important. They also noted that seemingly trivial insults could eventually lead to more serious problems and that even near misses could cause anxiety and diminished trust. Several members suggested that some of the errors might be due to offices being too busy, to physicians that are inadequately trained or who have not maintained their competence, to prejudice, and to the unintended consequences of managed care.

DISCUSSION

This study found that the medical errors related by patients in our sample are more likely to involve the breakdowns in the clinician-patient relationship and the access to clinicians than the technical errors that are the focus of current patient safety initiatives. The patients we interviewed spoke more about insensitivity and miscommunication than, for example, receiving the wrong drug prescription.

This perspective contrasts sharply with what recent research shows family physicians report. Physician reports are dominated by breakdowns in information transfer and ultimate treatment errors,12, 13 whereas our results suggest that patients cite problems of access and relationship, which are dominated by psychological injuries. Our findings resonate with others who have urged giving more attention to patient perspectives of medical errors25 and with recent surveys suggesting that the public and the medical community view patient safety through different lenses.16– 19

Our study has a number of potential limitations. First, the interview subjects were self-selected, and their personal experiences might not be representative of the general primary care population. Second, the respondents were asked to recall problematic incidents from their entire past experience, so their reports are likely to be the most recent or the most memorable incidents. Third, the modest sample size further limits the generalizability of our findings. Fourth, the proportions we report are sensitive to our typology and the validity of our denominators, which others might contest.

Finally, our report includes as errors a broad range of problematic experiences that might fall outside others’ sense of the term. As stated earlier, we conceive of errors as all forms of improper, delayed, or omitted care that unnecessarily injures patients by either worsening health outcomes or causing physical or emotional distress. We defend the inclusion of emotional distress as a legitimate, preventable harm—mistakes that cause patients to be frightened or humiliated are just as important as those that cause physical distress—but including emotional distress creates an indistinct boundary between medical errors and patient dissatisfaction. The frustration that patients experience with, for example, long appointment delays may be relevant to some and trivial to others. We recognize this difficulty, but we reasoned that it was preferable to use liberal boundaries to obtain a complete picture of what patients dislike about their care and to allow others to judge what subset of those problems they choose to label as errors. Further, we think it unwise to ignore the frustrating and dehumanizing experiences that erode a relationship which has caring as its imperative. One can also argue that whether the label of errors applies may be less important than recognizing the preventable harms associated with primary health care.

Layde et al26 remind us that injury prevention is the goal of quality improvement. The stories we solicited reverberated with recurring and troubling themes: You cannot get a human being on the telephone, and you cannot get an appointment. When you do have an appointment, you wait an excessive time before seeing the doctor, who is in a hurry, does not seem to care, and provides inadequate explanation and education. There were several stories of perceived racism. The interviews suggest a variety of experiences that can act to potentiate harmful outcomes and that may lead to a common final pathway for dissatisfaction and poor-quality care. Our study respondents received emotional injury in many ways, but each event had the potential to weaken the patient’s relationship with the clinician and culminate in loss of trust in the health care system. This outcome carries a potentially large public health burden given the principle that small disturbances in a large number of cases create a large population effect.

These narratives also underscore that deficiencies in every critical feature of the system—accessibility, timeliness, patient-centeredness, effectiveness, efficiency, and safety27—are capable of producing harm. As suggested recently by Lee,28 rather than focus on errors or any other particular segment in isolation, the totality warrants simultaneous attention. Illustrating a theme of To Err is Human,1 these stories of errors and harms speak to system design flaws that are amenable to analysis and change.15, 29 Some changes in primary care systems stimulated by consortia such as the Institute for Health-care Improvement30 (eg, open-access scheduling,31 electronic medical records32) might ameliorate some of the errors patients report, but they do not directly address the rushed, dehumanizing health care experiences that pervade our narratives. This aspect of our findings resonates with recent survey studies that show a decline in patient ratings of the quality of their interactions with their primary care physicians.33, 34

The current emphasis by the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) on professionalism in medical education35 and its enforcement of 80-hour resident workweeks36 are important efforts, but what of the persistent and considerable pressures on faculty and residents for clinical productivity? Will primary care clinicians, faced with increasing overhead from regulatory requirements and malpractice costs, be able, even if willing, to deliver patient-centered care? Will they be able to afford the quantity and quality of staff, and spend sufficient time with their patients? We believe it will require major reforms in medical education, in the financing of health care, and in the manner in which we deal with injuries associated with health care to alter the substrate for breakdowns in relationships with clinicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all those who told their stories for this study, and the 3 interviewers - Margaret Manning, Brenda McFail, and Yvonne Mathis. We also thank Tammy Butler and Susan Labuda Schrop for their secretarial and logistical support.

Conflicts of interest: none reported

Funding support: This project was supported by grant number U18 HS11117-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed]

- 2.Brennan TA, Leape, LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients: results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. New Engl J Med. 1991;324:370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson RM, Runciman WB, Gibberd RW, et al. The quality in Australian health care study. Med J Aust. 1995;163:458–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas EJ, Studdert DM, Burstin HR, et al. Incidence and types of adverse events and negligent care in Utah and Colorado. Med Care. 2000;38:261–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Survey Shows that Medical Errors and Malpractice Are Among Public’s Top Measures of Health Care Quality. Press release December 11, 2000. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Md. Available at: http://www.ahcpr.gov/news/press/pr2000/kffsurvpr.htm. Accessed March 23, 2003.

- 6.Reason J. Human Error. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1990.

- 7.White KL, Williams TF, Greenberg BG. The ecology of medical care. New Engl J Med. 1961;265:885–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green LA, Fryer GE, Yawn BP, Lanier D, Dovey SM. The ecology of medical care revisited. New Engl J Med. 2001;344:2021–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ely JW, Levinson W, Elder NC, Mainous AG III, Vinson D. Perceived causes of family physicians’ errors. J Fam Pract. 1995;40:337–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer G, Fetters MD, Munro AP, Goldman EB. Adverse events in primary care identified from a risk-management database. J Fam Pract. 1997;45:40–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhasale, AL, Miller GC, Reid SE, Brit HC. Analysing potential harm in Australian general practice: an incident-monitoring study. Med J Aust. 1998;169:73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dovey SM, Meyers DS, Phillips RL Jr, et al. A preliminary taxonomy of medical errors in family practice. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:233–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makeham MA, Dovey SM, County M, Kidd MR. An international taxonomy for errors in general practice: a pilot study. Med J Aust. 2002;177:62–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Academy of Family Physicians, Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Practice and Primary Care. Toxic cascades: a comprehensive way to think about medical errors. Am Fam Phys. 2001;63:847. Available at: http://www.aafppolicy.org/x161.xml. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vincent C, Taylor-Adams S, Chapman EJ, et al. How to investigate and analyse clinical incidents: clinical risk unit and association of litigation and risk management protocol. BMJ. 2000;320:777–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Patient Safety Foundation at the AMA. Public opinion of patient safety research findings. Available at: http://www.npsf.org/download/1997survey.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2003.

- 17.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National survey on Americans as health care consumers: an update on quality information. Available at: http://www.kff.org/content/2000/3093/Survey%20Highlights.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2003.

- 18.Robinson AR, Homan KB, Rifkin JI, et al. Physician and public opinion on quality of health care and the problem of medical errors. Arch Int Med. 2002;162:2186–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Brodie M, et al. Views of the public and practicing physicians on medical errors. New Engl J Med. 2002;347:1933–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuzel AJ, Woolf SH, Engel JD, et al. Making the case for a qualitative study of medical errors in primary care. Qual Health Res. 2003;13:743–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Clinical research: a multimethod typology and qualitative roadmap. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1999:3–30.

- 22.Miller WL, Crabtree BF. The dance of interpretation. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1999:127–143.

- 23.Cicourel A. Method and Measurement in Sociology. New York, NY: Free Press; 1964.

- 24.Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Fourth Generation Evaluation. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1989.

- 25.Vincent CA, Coulter A. Patient safety: what about the patient? Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:76–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Layde PM, Cortes LM, Teret SP, et al. Patient safety efforts should focus on medical injuries. JAMA. 2002;287:1993–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute of Medicine. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

- 28.Lee TH. A broader concept of medical errors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1965–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vincent C. Understanding and responding to adverse events. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1051–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Idealized design of clinical practice. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/idealized/idcop/index.asp. Accessed March 23, 2003.

- 31.Murray M, Tantau C. Same-day appointments: exploding the access paradigm. Fam Prac Manage. 2000:45–50. [PubMed]

- 32.Adams WG, Mann AM, Bauchner M. Use of an electronic medical record improves the quality of urban pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2003;111:626–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy J, Chang H, Montgomery JE, Rogers WH, Safran DG. The quality of physician-patient relationships: patient experiences 1996–1999. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Safran DG. Defining the future of primary care: what can we learn from patients? Ann Int Med. 2003;138:248–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swick HM, Szenas P, Danoff D, Whitcomb ME. Teaching professionalism in medical education. JAMA. 1999;282:830–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.ACGME duty hours standards now in effect for all residency programs. Available at: http://www.acgme.org. Accessed December 13, 2003.