Abstract

BACKGROUND Recent trials have shown improved depression outcomes with chronic care models. We report the methods of a project that assesses the sustainability and transportability of a chronic care model for depression and change strategy.

METHODS In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), a clinical model for depression was implemented through a strategy supporting practice change. The clinical model is evidence based. The change strategy relies on established quality improvement programs and is informed by diffusion of innovations theory. Evaluation will address patient outcomes, as well as process of care and process of change.

RESULTS Five medical groups and health plans are participating in the trial. The RCT involves 180 clinicians in 60 practices. All practices assigned to the clinical model have implemented it. Participating organizations have the potential to disseminate this clinical model of care to 700 practices and 1,700 clinicians.

CONCLUSIONS It is feasible to implement the clinical model and change strategy in diverse practices. Follow-up evaluation will determine the impact, sustainability, and potential for dissemination. Materials are available through http://www.depression-primarycare.org; more in-depth descriptions of the clinical model and change strategy are available in the online-only appendixes to this article.

Keywords: Depression; depressive disorder; health services research, program evaluation; primary health care; information dissemination; randomized controlled trials

INTRODUCTION

Improving depression outcomes in primary care has been a public health priority for at least a decade1 but remains elusive.2 Although research has shown improved outcomes with telephone care management and closer primary care and mental health collaboration,3– 11 the potential for dissemination and sustainability of these strategies has not been established.

The MacArthur Foundation has charged a group of clinicians and researchers to make a difference on a national scale in the primary care management of depression.12– 23 For more on this work, see Appendix 1, which can be found online only as supplemental data at http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/2/4/301/DC1. Additional momentum comes from the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) through its endorsement of depression screening in adults24 “in clinical practices that have systems in place to assure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and careful follow up.” They state, “Benefits from screening are unlikely to be realized unless such systems are functioning well.”

The jump from the page to the practice is long.25 This report describes (1) a broadly applicable evidence-based clinical model of depression care, (2) a practice change strategy, and (3) the methods of a project to evaluate their impact.

METHODS

The Re-Engineering Systems for Primary Care Treatment of Depression (RESPECT-Depression) project includes a randomized controlled trial (RCT) and subsequent evaluations of sustainability and dissemination of information. The design is described in Appendix 2, available online only as supplemental data at http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/2/4/301/DC1.

Health care organizations (HCOs) invited to participate included medical groups and health plans that provide quality improvement support to affiliated practices. HCO leaders were willing to commit to ongoing support for the clinical model and to disseminate it to additional practices through the practice change strategy if the model was beneficial.

The Clinical Model

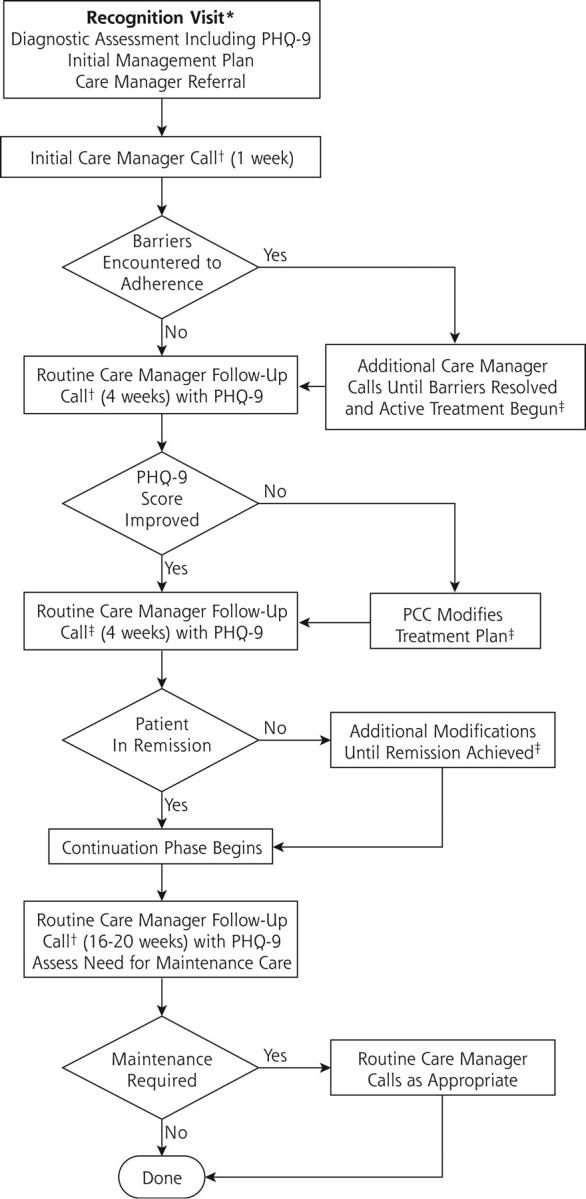

The Three Component Model (TCM) enhances care17 by providing a system for depression management as recommended by the USPSTF (Figure 1 ▶). Components include care management, collaboration between mental health and primary care professionals, and preparation of primary care clinicians and practices to provide systematic depression management. Patient response is monitored across components by using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).26– 28 Similar systematic approaches have improved preventive care.29– 31

Figure 1.

The Three Component Model.

* Primary Care Clinician (PCC) follow up visits typically at 2, 6, and 12 weeks and as needed; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire

† After each patient contact, Care Manager sends report to PCC and discusses in psychiuatry supervision call.

‡ Discussed with psychiatrist or referral to specialty care.

The primary care clinician is responsible for recognition, diagnostic evaluation, and initial management of depression, as well as follow-up care. Clinicians receive training in the model and are thus prepared to provide systematic care. Patients who agree to participate receive telephone support calls from a practice-based or centrally-based care manager at 1, 4, and 8 weeks after the initial primary care visit and additional telephone calls every 4 weeks thereafter until remission. Through weekly supervision telephone calls, care managers discuss patient contacts with a psychiatrist from their health care organization. Based on these discussions, psychiatrists may provide feedback to primary care clinicians if they have suggestions about management. A more complete description of the clinical model is found in Appendix 3, available online only as supplemental data at http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/2/4/301/DC1).

The Practice Change Strategy

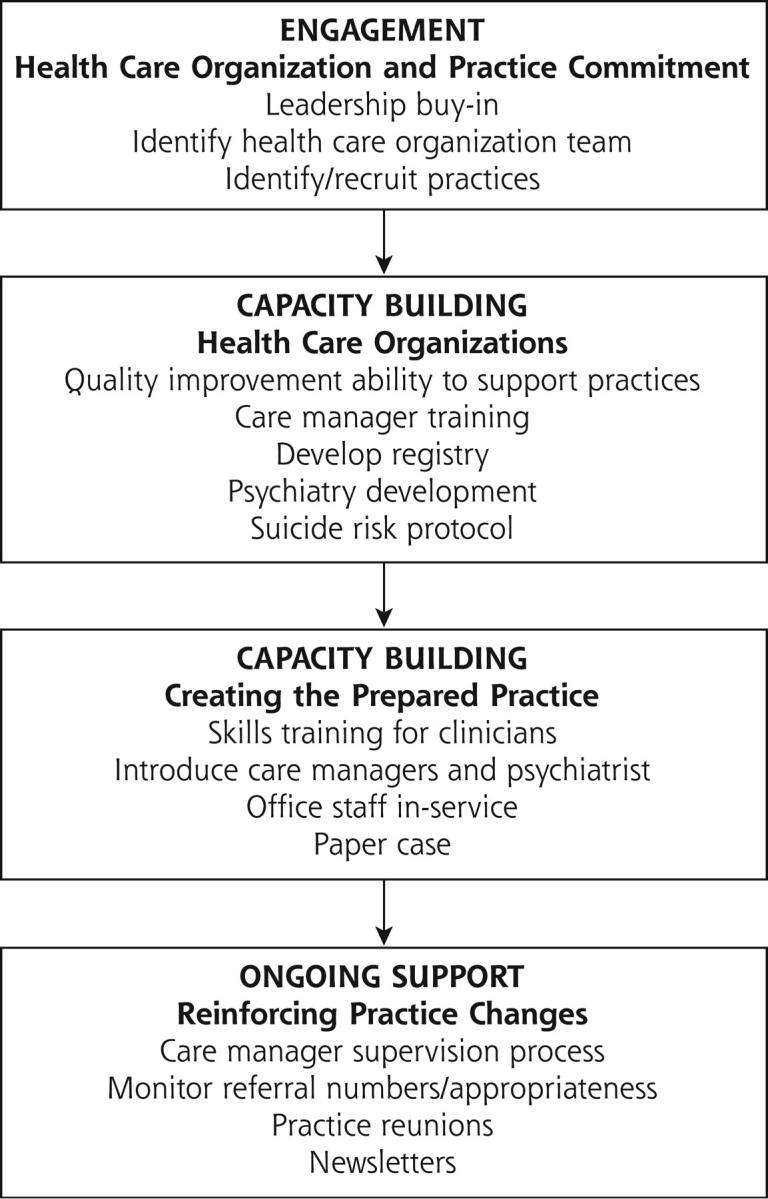

This strategy supports a process of change for clinicians and practices to apply and maintain the clinical model (Figure 2 ▶). Key principles, which derive from diffusion of innovations theory,32 include working initially with practices and clinicians that not only have an interest in the innovation and view it as compatible with their needs, values, and resources, but also have the ability to try it with minimal investment and observe its impact. A more complete description can be found in Appendix 4, available online only as supplemental data at http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/2/4/301/DC1.

Figure 2.

The process of change strategy.

Evaluation

Clinician surveys and care manager logs describe the process of care. Clinical progress is assessed using PHQ-9. For the RCT, depression severity and functional health of patients are determined at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months through telephone interviews conducted by independent evaluation center staff using validated instruments.33, 34 Care manager logs and HCO administrative data are used to assess cooperation with implementation and changes in the process of care in each practice. For a more complete description, see Appendix 5, available online only as supplemental data at http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/2/4/301/DC1.

RESULTS

Six HCOs initially agreed to serve as collaborating institutions: 3 medical groups and 3 insurance plans, 1 of which is a behavioral health network. These HCOs were recruited to reflect the diversity of organizations nationally and because of their interest in enhancing depression care. One HCO dropped out as a result of leadership changes before enrolling patients in the RCT. The remaining 5 organizations, which engaged 60 practices and 180 clinicians in the RCT, have more than 700 practices and 1,700 clinicians as potential targets for the clinical care model.

All assigned practices were able to implement the TCM. Nine hundred eighty-seven consenting patients were referred to the evaluation center. Of these, 433 were eligible for the evaluation cohort and completed baseline interviews. Appendix 6 (available online only as supplemental data at http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/2/4/301/DC1) provides more detail.

DISCUSSION

The RESPECT-Depression project is evaluating the ability of the practice change strategy to sustain and disseminate the evidence-based clinical model. The clinical model has so far been used with hundreds of patients in the intervention practices, with implementation support provided by the 5 HCOs. An evaluation cohort of depressed patients will allow assessment of 6-month depression outcomes in initial practices late in 2003, and sustainability and dissemination results will be available in 2004–2005.

To our knowledge, the RESPECT-Depression project is among the first to link a randomized controlled trial to subsequent dissemination. The RESPECT-Depression project does require new care management resources, as well as a supportive role from psychiatrists, but the 5 HCOs have indicated a willingness to maintain these supports using their own resources. Finally, the RESPECT-Depression project relies on a widely available resource, quality improvement programs of health care organizations, to help clinicians and practices make the jump from the page to the practice in implementing the enhanced model of care. Additional discussion is available online only as supplemental data in Appendix 7 at http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/2/4/301/DC1).

The RESPECT-Depression project will add to the knowledge base about effective management of depression in primary care . Materials needed to build clinician and care manager capacity to apply the clinical model are available at http://www.depression-primarycare.org, as are materials needed by quality improvement offices to support its implementation through the change strategy.

These materials and the manuals that support their use allow a turnkey approach to implementation in which a simple system has been engineered to accomplish a complex task using proven methods that allow customization. Clinicians supported by quality improvement infrastructures should demand support for implementing such evidence-based practice enhancements. In addition, this project will contribute to the development of research methods that address translation, sustainability, and dissemination of innovations in primary care. In so doing, it helps set the stage for a new generation of research studies using quality improvement structures to support sustained and widespread application of evidence-based best practices.

Conflicts of interest: none reported

Funding support: This research is sponsored by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Depression in Primary Care: Treatment of Major Depression. Vol 2. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1993. Publication AHCPR 93–0511.

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md; US Department of Health and Human Services; 1999.

- 3.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: Impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:924–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care. JAMA. 2000;283:212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunkeler E, Meresman J, Hargreaves W, et al. Efficacy of nurse tele-health care and peer support in augmenting treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:700–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon GE, VonKorff M, Rutter C, Wagner E. Randomised trial of monitoring, feedback, and management of care by telephone to improve treatment of depression in primary care. BMJ. 2000;320:550–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katzelnick DJ, Simon GE, Pearson SD, et al. Randomized trial of a depression management program in high utilizers of medical care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rost K, Nutting P, Smith JL, Elliott CE, Dickinson M. Managing depression as a chronic disease: a randomised trial of ongoing treatment in primary care. BMJ. 2002;325:934–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulberg HC, Block MR, Madonia MJ, et al. Treating major depression in primary care practice. Eight-month clinical outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996,53:913–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dietrich AJ. The telephone as a new weapon in the battle against depression. Eff Clin Pract. 2000;4:191–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nutting PA, Rost K, Dickinson M, et al. Barriers to initiating depression treatment in primary care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:103–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solberg LI, Fischer LR, Wei F, et al. A CQI intervention to change the care of depression: a controlled study. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4:239–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Taylor-Vaisey A, Dietrich AJ, Oxman TE. Interventions to improve provider diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in primary care: a critical review of the literature. Psychosomatics 2000;41:39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Learman LA, Gerrity MS, Field DR, van Blaricom A, Romm J, Choe J. Effects of a depression education program on residents’ knowledge, attitudes, and clinical skills. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oxman TE, Dietrich AJ, Williams JW, Kroenke K. The Three Component Model of depression management in primary care. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams JW, Rost K, Dietrich JW, Ciotti MC, Zyzanski SJ, Cornell J. Primary care physicians’ approach to depressive disorders: effects of physician specialty and practice structure. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerrity MS, Cole SA, Dietrich AJ, Barrett JE. Improving the recognition and management of depression: is there a role for physician education? J Fam Pract. 1999;48:949–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerrity MS, Williams JW, Dietrich AJ, Olson AL. Identifying physicians likely to benefit from depression education: a challenge for health care organizations. Med Care. 2001;39:856–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole S, Raju M, Barrett J, Gerrity M, Dietrich A. MacArthur Foundation depression education for primary care physicians: background, participant’s workbook, and facilitator’s guide. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22:299–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams JW, Barrett J, Oxman T, et al. Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: a randomized controlled trial in older adults. JAMA. 2000;284:1519–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrett JE, Williams JW, Oxman TE, et al. Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: a randomized trial in patients aged 18 to 59 years. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:405–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pigone MP, Gaynes BN, Rushton JL, et al. Screening for depression in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greer AL. The state of the art versus the state of the science. The diffusion of new medical technologies into practice. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1988;55:5–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression and diagnostic severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:509–521. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dietrich AJ, O’Connor GT, Keller A, Carney PA, Levy D, Whaley FS. Improving cancer early detection and prevention: a community practice randomized trial. BMJ. 1992;304:687–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson R, O’Donnell L, Johnson C, et al. Office systems intervention to improve DES screening in managed care. Obstet and Gynec. 2000;96:380–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bordley WC, Margolis PA, Stuart J, Lannon C, Keyes L. Improving preventive service delivery through office systems. Pediatrics. 2001;108:e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York, NY: The Free Press; 2003.

- 33.Derogatis L, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth E, et al. The Hopkins Check List: a measure of primary symptoms. In Pichot P, ed. Psychological Measurements in Psychopharmacology: Problems in Psychopharmacology. Basel, Switzerland: Kargerman; 1974:79–110.

- 34.Epping-Jordan J, Ustun T. The WHODAS-II: leveling the playing field for all disorders. WHO Mental Health Bulletin. 2000;6:5–6. [Google Scholar]