Abstract

PURPOSE We wanted to explore the context of help seeking for reproductive and nonreproductive health concerns by urban adolescent girls.

METHODS We undertook a qualitative study using in-depth interviews of African American and Latina girls (n = 22) aged 13 to 19 years attending public high schools in the Bronx, NY.

RESULTS Before the onset of sexual activity, most girls meet health needs within the context of the family, relying heavily on mothers for health care and advice. Many new needs and concerns emerge at sexual debut. Key factors modulating girls’ ability to address their health needs and concerns include (1) the strategy of selective disclosure of information perceived to be harmful to close family relationships or threaten privacy; (2) the desire for personalized care, modeled on the emotional and physical care received from mother; and (3) relationships with physicians that vary in quality, ranging from distant relationships focused on providing information to close continuity relationships. Core values shaping these processes include privacy, a close relationship with the mother, and a perception of sexual activity as dangerous. No girl was able to meet her specific reproductive health needs within the mother-daughter relationship. Some find nonmaternal sources of personalized health care and advice for reproductive health needs, but many do not.

CONCLUSIONS Adolescent girls attempt to meet reproductive health needs within a context shaped by values of privacy and close mother-daughter relationships. Difficulty balancing these values often results in inadequate support and care.

Keywords: Adolescents, female; women’s health; health care seeking behavior; qualitative research; minority groups

INTRODUCTION

Adolescence is marked by the emergence of sexual behaviors that may lead to sexually transmitted infections (STIs), their sequelae, and unplanned pregnancy. Reproductive health services promote sexual health by providing access to contraception, STI screening, and counseling. Despite the need for such services, many youth acknowledge considerable delay between the onset of sexual activity and initiation of risk-appropriate services1,2 and report missing needed care.3,4 Minority youth are at especially high risk for negative consequences of sexual activity.5 Compared with white youth, those of ethnic minority groups are less likely to have a usual source of care,6 are less likely to receive fewer ambulatory services,7 and are more likely to have unmet health needs.4,6

Formal care seeking for reproductive health needs is apt to be influenced by informal care seeking and lay referral, yet studies of these processes, especially for vulnerable urban youth, have rarely been reported. In this study we used in-depth interviews to understand the barriers related to seeking reproductive health care in inner-city adolescent girls by exploring sources of advice and strategies for seeking help.

METHODS

Setting

Participants were adolescent girls attending 2 Bronx, NY, public high schools serving a largely minority, multiethnic, low-income community.

Data Collection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the New York City Board of Education. All 65 young women in 5 classrooms were invited to participate, and 26 returned signed parental consents. Those present on interviewing days (22 of 26) furnished an informed consent before being interviewed privately, in English or Spanish, by 1 of 2 trained female, ethnic minority research assistants. Consistent with our approval from the Board of Education, detailed notes were taken, with transcripts typed immediately to obtain nearly verbatim records.

The Interview

To understand the familial and social context of illness and care seeking, data were collected on both nonsexual and sexual health needs. Participants generated narratives on 3 types of health problem: pain, a cold, and a reproductive health issue. Structured prompts were used to elicit narratives. Prompts were derived from the Illness Self Regulation Model,8,9 which provided a framework for systematic exploration of cause, consequence, timeline, course, prevention, and treatment for each health concern. Additional prompts explored lay consultation, formal treatment seeking, and the rationale for each. Details of the interview guide are presented in Appendix 1 (which can be found online only at: http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/2/6/549/DC1).

Analysis

The analysis team included the principal investigator (a family physician), a psychologist coinvestigator, and a sociologist not involved in developing the study hypotheses or methods. The team underwent a reflexivity exercise10 designed to expose preconceptions and expectations regarding findings. Details of the reflexivity exercise are available in Appendix 2 (which can be found online only at: http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/2/6/549/DC1).

The analysis focused on unmet need and variables contributing to or modifying it. Team members independently coded transcripts to identify themes. A tentative coding scheme emerged that included dimensions of the self-regulation model, such as cause, perceived consequences, and treatment seeking. Coding differences were explored in group meetings. Once consensus was achieved, a final coding scheme was developed and applied using NVivo software (QSR International Pty Ltd) to facilitate the retrieval of text passages.

After coding 8 interviews, we developed a theoretical model comparing patterns of help seeking for girls who were successful in meeting their health needs with patterns for girls who were not. The fit of this model was tested and refined by exploration of the remaining 14 interviews, including an explicit search for disconfirming cases.

RESULTS

The 22 participants were Latina (n = 14), African American (n = 5), or of Caribbean descent (n = 3). Three interviews were conducted in Spanish. Participants were in grades 9 through 12. Fifteen reported that they had been sexually active.

Lay Referral Processes for Nonreproductive Health Concerns

We first inquired in detail about girls’ experiences with nonreproductive health problems. A variety of health issues were described, including acute illnesses, orthopedic problems, grief, and puberty issues. For such problems, initial health seeking took place entirely within the family. Almost without exception, mothers or mother surrogates were described as the source of health care and advice for nonreproductive health problems: “I talked to my mom the most about [the cold]. I complained to my friend, but, you know, she could only tell me that she hoped I felt better. Mommy’s the one who took care of me.”

Girls described the relationships with their mothers in idealized terms, characterizing them as uniquely close: “My mom brought me into the world, and I trust her. It’s different from her than when I speak to my dad.”

We found that the care and advice the mothers provided during illness was an important context for expressing highly valued closeness between mothers and daughters. The caring approach of mothers was sometimes contrasted with that of other family members: “She’s always there when I’m sick.… She’s always been there. Always my mom, not my dad.”

In the rare cases where mothers did not provide nurturing health care to daughters, it was usually an indication of a disturbed relationship: “I don’t know if I could call her a hypocrite, or if she just don’t care. Like if somebody’s there, she’ll act all concerned, like she’ll tell me she’ll rub my stomach or my back, but if nobody’s over, then she’ll tell me to just lie down.”

Privacy also emerged as a key value shaping how girls sought health advice and care. Girls believed that most personal problems are best handled within the context of the family: “My parents told me not to trust anybody, not to talk to anybody, not even doctors.”

Thus the high value placed on close mother-daughter relationships and privacy, both elements of familism, shaped girls’ preferences and patterns of seeking health care for nonreproductive health problems.

Me-Care

Girls’ descriptions of their illness experiences reveal an idealized notion of health care modeled on the care provided by mothers during illness. We labeled this category “me-care” because it is intimate, personal, and highly focused on the specific needs of the individual.

Though providing reliable information may be important, me-care is valued because it provides much more than information. Me-care provides emotional as well as physical care, made possible because care is provided in the context of a close relationship between the girl and her caregiver: “[I got help from my mother and sister] together.… We’re the girls in the house and we’re close. My mom is very interested in my health and she fixes me.”

The Crisis at Sexual Debut

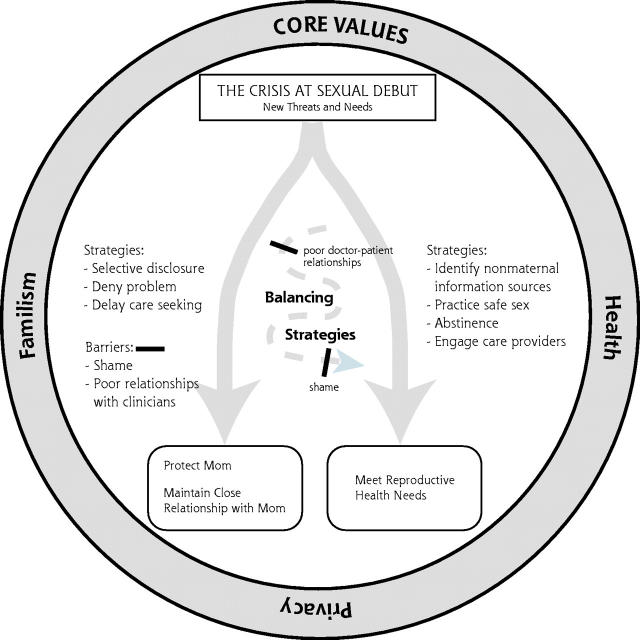

Sexual debut is a crisis point for girls. Faced with new needs, girls must find new sources of advice and care for reproductive health problems while continuing to protect the mother-daughter relationship. Girls used a variety of strategies in the context of important values of familism and privacy. Figure 1 ▶ depicts the difficult task of balancing 2 desired outcomes.

Figure 1.

Balancing the desired outcomes of privacy and relationship with mother and meeting reproductive health needs.

New Threats at Sexual Debut

A variety of new needs associated with sexual activity were described, including the need for information, screening, and family planning and the need for diagnosis and treatment of symptoms. Almost without exception, sexual activity was understood as profoundly threatening to physical health, privacy, relationships within the family, and ultimately to one’s future. Concerns about damage to one’s body and future fertility were especially common: “A year and a half ago I was diagnosed with chlamydia. Now I’m worried, because in my health classes they tell me that it can cause infertility and PID [pelvic inflammatory disease]. I’m afraid that I might have something serious, and I don’t want to find out.”

Girls also feared serious social consequences of sexuality, frequently expressing fears that disclosing sexual activity would threaten important family relationships: “[If I missed a period,] I would talk to my mom, but only after I was sure that I was actually pregnant. My parents have an idea about me one way, and they would find out that I’m different.…They would just be let down.”

Concern about harming the mother-daughter relationship reflected that girls were concerned with issues of social mobility. A common theme was the longing of mothers for their daughters to escape the poverty of the inner city: “I don’t want to disappoint [my mom]. She wants me to wait. She wants me to have the house … you know, the house, the husband, the 3.5 kids.”

Strategies to Protect Family Relationships

Despite the identification of mothers as the best sources of care and advice in general, girls were unable to turn to their mothers to meet reproductive health needs. Girls consistently used a strategy of selective disclosure of information related to sexual activity and the health needs associated with it. Though a few feared punishment, selective disclosure was more often used to avoid damaging familial relationships. Many girls shared this young woman’s fear of disappointing her mother: “[I can’t go to her because] I’m not supposed to be having sex or anything. I’m too young and she doesn’t expect me to, so I don’t tell her that and bring her down.”

Yet the girls felt ambivalent about selective disclosure. They often stated, “I can tell my mom anything,” only to contradict themselves in the same breath: “I can talk to [my mom] about anything, but I choose not to talk to her about everything.”

The contradiction reflects tension between the desired closeness between mother and daughter, symbolized by the ability to “tell mom anything,” and the perceived danger of full disclosure.

Meeting Health Needs after Sexual Debut

Nonmaternal Sources of Advice

Most girls sought nonmaternal sources of advice for sexual health problems. Commonly mentioned confidants included female friends, sisters, other female relatives, and occasionally other female adults. The qualities of a trusted confidant include a perceived ability to relate to the issue, a close relationship with the confidant, and privacy. Though girls frequently turned to age mates and siblings, they described these confidants as providing support, but rarely as sources of specific information or actual care: “[If I had an STD] I would go to my friend because I know she would help me in any way she can … and do what a friend is supposed to do. She’d be there for me.”

By contrast, in a few cases, older female family members were important sources of advice. Such mother alternatives were valued because they could provide guidance based on knowledge and experience, while maintaining the familial context of care: “[My older sister] has children of her own. She knows me … and she knows about pregnancy. She doesn’t freak out like my mom when I tell her stuff. She’s more understanding.”

Turning to Health Care Clinicians

Facing new needs, some girls turned to health care clinicians. The quality of these relationships varied substantially. Of sexually active girls, 6 of 15 had established close, trusting relationships. The qualities sought in professional caregivers were similar to the qualities valued of confidants and familial caregivers, including closeness, ability to relate, and privacy. Girls who had established more close and trusting relationships described interactive exchanges with their doctors, viewed clinicians as persons, and often described a personal bond: “I’ve been seeing her all my life, and she said I can still come to see her.… She tells me to do well in school, no drugs, no pregnancy.… She’s nice. We have things in common. She has teenage daughters. I think she communicates with me and most doctors should do that.”

In effect, some young women find an alternative to the me-care previously provided by mothers and are able to meet reproductive health needs within a clinician-patient relationship rather than within the family: “I feel more comfortable with [my regular doc] than with my parents, because I don’t see her everyday, and she gives me helpful information and tells me about different experiences … that she sees and what can happen to you different from your parents. [Parents] tell you not to do it but don’t explain what can happen to you.”

In contrast, when an intimate relationship with a clinician was lacking, girls tended to describe encounters with physicians as merely an exchange of information: “Doctors give you papers saying what to do.”

In these shallow relationships with health care clinicians, girls emphasized doctors’ inability to provide personalized advice: “I have a doctor, and he talks to me, but I really don’t listen.… I don’t feel like he knows my body or what I go through.”

Unmet Need

Unmet need was reported for 10 of the 15 sexually experienced girls in our sample. Examples are listed in Table 1 ▶. Among these are fears of pregnancy, infections, and infertility that were not addressed in health care settings, as well as inadequate birth control. Girls often reported intense distress associated with unmet need. In the following example, a young woman describes ongoing guilt and anguish related to an undiagnosed pregnancy and miscarriage: “I didn’t get my period, I skipped a month, and I was throwing up, eating a lot, I got into a fight … she punched me in the stomach and, after that, I think I lost the baby because my period came down. I smoked, I drank, did not think about these things. I was unsure of what to do or how to treat my body.”

Table 1.

Examples of Unmet Reproductive Health Need

| Health Issue | Number* |

| Fear of or actual unplanned pregnancy | 6 |

| Fear of infertility | 3 |

| Unaddressed concerns about contraception | 3 |

| Unaddressed concerns about STIs | 2 |

| Delayed care seeking for STI | 2 |

| Latex allergy | 1 |

| Undiagnosed miscarriage | 1 |

| Ovarian cyst, amenorrhea | 1 |

STI = sexually transmitted infection.

*In some cases girls described more than one unmet need.

Another participant reports ongoing unprotected sex because of an apparent latex allergy, though she fears the consequences and has had no professional advice: “I get lots of discharge and my vagina swells after intercourse. I can’t use condoms … I thought it was supposed to happen because I lost my virginity but then it continued to happen so I didn’t know what was goin’ on.”

The lack of a close relationship with a professional health caregiver was associated with unmet need (Table 2 ▶). Of the 6 with close relationships, only 1 described a major unmet need—delay in evaluation for a feared STI. By contrast, of the 9 girls who had no such relationships, all had ongoing unmet need. Interestingly, older girls (aged 16 years or older) were more likely to describe trusting relationships (6 of 9), whereas none of the younger girls had such relationships.

Table 2.

Trusting Relationships With Health Care Clinicians and Unmet Need for Sexually Active Girls (n = 15)

| Trusted Clinician | No Trusted Clinician | |||

| Age | Needs Met | Needs Unmet | Needs Met | Needs Unmet |

| <16 y | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| >16 y | 5 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

DISCUSSION

Patterns of care seeking, previously located within the family, shift dramatically at sexual debut. Frightening new sexual health needs challenge previously established familial health-seeking strategies. Girls cope by being selective in disclosing information perceived to be harmful to family relationships, especially with their mothers, or to threaten privacy. Girls want personalized care modeled on the emotional and physical care received from their mothers. They extend their search for this type of advice and care to mother alternatives, such as older female family members.

The poignant descriptions of our participants indicate that the transition from familial care seeking to nonfamilial sources is difficult, especially given the intensity of girls’ concerns. Girls experienced their sexual health needs as intimately tied to personhood and individuality, to their emotional needs, and to their adult futures. Peers provide support but not adequate help, and relationships with health care clinicians are often absent or too shallow to be a source of the desired personalized care. Those who find sources of personalized reproductive health advice and care, including trusting continuity relationships with health care clinicians, are able to address reproductive health needs. For those who fail to establish this type of relationship, sexual health needs are very likely to remain unmet.

Tolman et al17 recently published an ambitious effort to construct a comprehensive model of adolescent sexual health. Her model moves away from an exclusive focus on risky sexual behavior and stresses the importance of gender norms in promoting or undermining sexual health. She stresses the need to explore the “tensions adolescents experience while trying to make sense of their own sexuality.” Our model reflects one such tension, the balance of meeting the need reproductive health care while protecting relationships in the family. Tolman makes a strong case for the importance of exploring personal and cultural meanings attached to sexual activity, for example those embedded in the context provided by girls’ race and ethnicity. According to Tolman et al, encompassing the individual and relational aspects of sexuality are broader social and dominant cultural conceptions. These conceptions include the view of female sex as passive, devoid of desire, and subordinate to male needs.

In Fine’s classic work with urban girls, she noted the “missing discourse of desire” among adults providing sexual education.18 Their messages focused on victimization, moralization, and disease, failing to acknowledge or support healthy sexuality for urban girls. Two decades later, the inner-city girls in our study focused on danger, and narratives describing pleasure were rare. We hypothesize that the urban girls in our study have internalized the safe sex message, ever more common in the era of AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), as well as the fears of early pregnancy consistently heard from their mothers. They remain essentially mired in negative constructions of female sexuality.

The level of distress experienced by the young women in our sample related to reproductive health was striking. The pervasive view of sexual activity as dangerous warrants attention from clinicians. From this sample, it appears that awareness of the risks of unprotected sexual activity is very high. Importantly, girls’ fears are closely linked to the perception that sexual activity represents a threat to their chances of succeeding in life, including the potential to become mothers and, in this inner-city sample, to enter the middle class. In providing comprehensive care appropriate to the needs of young women, clinicians need to elicit the often unspoken fears related to reproductive health that are sources of distress and empower girls to manage the risk associated with sexual activity. Future research should attempt to assess and quantify systematically the distress associated with unmet reproductive health needs and seek to identify not only predictors of distress but also effective strategies to minimize it.

Limitations are introduced by the interview methods. That the interviews were not audiotaped perhaps resulted in less than exact reconstruction of the narrative; however, the interviewers used extensive notes and immediate transcription to minimize this limitation. About one third of our potential sample volunteered to participate. Yet despite the potential to yield a biased sample, we were impressed at the diversity of the final sample with regard to age, sexual activity, age at sexual debut, and relationships with health care clinicians. Although it is clear that many girls fail to establish close relationships with clinicians, in this hypothesis-generating study we are unable to determine the extent to which this reflects clinician behavior, traits of the adolescent, or other barriers.

Our sample included a broad age spectrum, which is potentially a problem because differences in developmental stage may independently influence care-seeking behavior. Previous studies suggest that younger age at sexual debut places girls at greater risk for negative consequences of sexual activity.11,12 Our finding that older girls were more likely to have trusting relationships with health care clinicians may reflect greater ability to seek out and overcome barriers to using health resources, but conclusions based on this small sample would be unjustified. Perhaps the process of shifting from maternal to nonmaternal sources of advice is simply too difficult for younger girls. Future studies should address age as a potentially important variable in girls’ ability to find nonmaternal sources of advice and care.

Our data suggest a need to improve access to personalized, supportive care for those who lack it. Clinician behaviors that can facilitate more effective relationships with adolescent girls are evident in the narratives. Our finding that confidentiality is a central concern is consistent with previous research.13–16 Health caregivers for adolescent girls must strive to create an atmosphere where girls perceive that privacy is protected. Beyond confidentiality, however, for the adolescent girls in our study, ideal care is patient-centered.17 Girls want clinicians who know them personally, and they want to know their clinicians as well. They want warmth, and they want clinicians to know “what they go through.” In short, they want a health care relationship that serves in some respects as a mother alternative, modeled after the kind of care previously received for nonreproductive health problems. Such relationships may be established in health care, school, or community settings, but they cannot be established in the absence of continuity, which is often lacking in inner-city health care settings.18,19

Acknowledgments

We thank Will Miller for his encouragement and guidance.

Conflicts of interest: none reported

Funding support: This research was funded by a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar Award (to MDM).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bar-Cohen A, Lia-Hoagberg B, Edward L. First family planning visit in school-based clinics. J Sch Health. 1990;60:418–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hillard P. Adolescent Pap smear screening: yes or no. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1996;9:93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein JD, Wilson K, McNulty M, Kaplan C, Collins K. Access to medical care for adolescents: results from the 1997 Commonwealth Fund survey of the health of adolescent girls. J Adol Health. 1999;25:120–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmer-Gembeck M, Alexander T, Nystrom R. Adolescents report their need for and use of health care services. J Adolescent Health. 1997;21:388–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aral SO, Holmes KK. The epidemiology of sexual behavior and sexually transmitted diseases. In: Holmes KK, ed. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1990.

- 6.Lieu T, Newacheck P, McManus M. Race, ethnicity, and access to ambulatory care among US adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:960–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aten M, Siegel D, Roghmann K. Use of health services by urban youth: a school based survey to assess differences by grade level, gender and risk behavior. J Adol Health. 1996;19:2–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leventhal H, Diefenbach M, Leventhal E. Illness cognition: using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognitive interactions. Cognit Ther Res. 1992;16:143–163. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. The common-sense representation of illness danger. In: Rachman S, ed. Medical Psychology. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Pergamon Press; 1980.

- 10.Barry CA, Britten N, Barber N, Bradley C, Stevenson F. Using reflexivity to optimize teamwork in qualitative research. Qual Health Research. 1999;9:26–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenthal SL, Biro FM, Succop PA, Cohen SS, Stanberry LR. Age at first intercourse and risk of STD. Adolesc Pediatr Gynecol. 1994;7:210–213. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santelli JS, Beilenson P. Risk factors for adolescent sexual behavior, fertility and sexually transmitted diseases. J Sch Health. 1992;62:271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein J, Slap G, Elster B, Schonberg S. Access to health care for adolescents: a position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adol Health. 1992;13:162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapphahn C, Wilson K, Klein J. Adolescent girls’ and boys’ preferences for provider gender and confidentiality in their health care. J Adol Health. 1999;25:131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng T, Savageau JA, Sattler AL, DeWitt TG. Confidentiality in health care: a survey of knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes among high school students. JAMA. 1993;269:1404–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein JD, McNulty M, Flatau CN. Adolescents’ access to care: teenagers’ self-reported use of services and perceived access to confidential care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tolman D, Striepe MI, Harmon T. Gender matters: constructing a model of adolescent sexual health. J Sex Res. 2003;40:4–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fine M. Sexuality, schooling, and adolescent females: the missing discourse of desire. Harv Educ Rev. 1988;58:29–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1087–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cornelius LJ. The degree of usual provider continuity for African and Latino Americans. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1997;8:170–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Malley AS, Forrest CB. Continuity of care and delivery of ambulatory services to children in community health clinics. J Community Health. 1996;21:159–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]