Abstract

BACKGROUND Recognizing fundamental flaws in the fragmented US health care systems and the potential of an integrative, generalist approach, the leadership of 7 national family medicine organizations initiated the Future of Family Medicine (FFM) project in 2002. The goal of the project was to develop a strategy to transform and renew the discipline of family medicine to meet the needs of patients in a changing health care environment.

METHODS A national research study was conducted by independent research firms. Interviews and focus groups identified key issues for diverse constituencies, including patients, payers, residents, students, family physicians, and other clinicians. Subsequently, interviews were conducted with nationally representative samples of 9 key constituencies. Based in part on these data, 5 task forces addressed key issues to meet the project goal. A Project Leadership Committee synthesized the task force reports into the report presented here.

RESULTS The project identified core values, a New Model of practice, and a process for development, research, education, partnership, and change with great potential to transform the ability of family medicine to improve the health and health care of the nation. The proposed New Model of practice has the following characteristics: a patient-centered team approach; elimination of barriers to access; advanced information systems, including an electronic health record; redesigned, more functional offices; a focus on quality and outcomes; and enhanced practice finance. A unified communications strategy will be developed to promote the New Model of family medicine to multiple audiences. The study concluded that the discipline needs to oversee the training of family physicians who are committed to excellence, steeped in the core values of the discipline, competent to provide family medicine’s basket of services within the New Model, and capable of adapting to varying patient needs and changing care technologies. Family medicine education must continue to include training in maternity care, the care of hospitalized patients, community and population health, and culturally effective and proficient care. A comprehensive lifelong learning program for each family physician will support continuous personal, professional, and clinical practice assessment and improvement.

Ultimately, systemwide changes will be needed to ensure high-quality health care for all Americans. Such changes include taking steps to ensure that every American has a personal medical home, promoting the use and reporting of quality measures to improve performance and service, advocating that every American have health care coverage for basic services and protection against extraordinary health care costs, advancing research that supports the clinical decision making of family physicians and other primary care clinicians, and developing reimbursement models to sustain family medicine and primary care practices.

CONCLUSIONS The leadership of US family medicine organizations is committed to a transformative process. In partnership with others, this process has the potential to integrate health care to improve the health of all Americans.

PREFACE

Recognizing growing frustration among family physicians, confusion among the public about the role of family physicians, and continuing inequities and inefficiencies in the US health care system, the leadership of 7 national family medicine organizations initiated the Future of Family Medicine (FFM) project in 2002. The goal of the project was to transform and renew the specialty of family medicine to meet the needs of people and society in a changing environment.

The work of the FFM project was overseen by the Project Leadership Committee, composed of representatives from the sponsoring organizations: the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation, the American Board of Family Practice, the Association of Departments of Family Medicine, the Association of Family Practice Residency Directors, the North American Primary Care Research Group, and the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine.

The project received financial support from the 7 family medicine organizations and from a combination of other supporters listed on page S30. The project was staffed by the American Academy of Family Physicians and organized to accomplish its charge through the work of 5 task forces. Task force members included individuals from diverse fields, drawing from a broad representation of health care professionals concerned with primary care, policy makers, and representatives of the patient voice. The task forces vetted and modified this work based on important input from reactor panels with diverse membership.

The 5 task forces and their charges were as follows:

Task Force 1: To consider the core attributes and values of family medicine and propose ideas about reforming family medicine and primary care to meet the contemporary needs and expectations of the people of the United States. The final report, “Task Force Report 1. Report of the Task Force on Patient Expectations, Core Values, Re-Integration, and the New Model of Family Medicine,” is available online at http://www.annfammed.org/content/vol2/suppl_1/index.shtml.

Task Force 2: To determine the training needed for family physicians to deliver core attributes and system services. The final report, “Task Force Report 2. Report of the Task Force on Medical Education,” is available online at http://www.annfammed.org/content/vol2/suppl_1/index.shtml.

Task Force 3: To ensure that family physicians deliver core attributes and system services throughout their careers. The final report, “Task Force Report 3. Report of the Task Force on Continuous Personal, Professional, and Practice Development in Family Medicine,” is available online at http://www.annfammed.org/content/vol2/suppl_1/index.shtml.

Task Force 4: To determine strategies for communicating the role of family physicians within medicine and health care, as well as to purchasers and consumers. The final report, “Task Force Report 4. Report of the Task Force on Marketing and Communications,” is available online at http://www.annfammed.org/content/vol2/suppl_1/index.shtml.

Task Force 5: To determine family medicine’s leadership role in shaping the future health care delivery system. The final report, “Task Force Report 5. Report of the Task Force on Family Medicine’s Role in Shaping the Future Health Care Delivery System,” is available online at http://www.annfammed.org/content/vol2/suppl_1/index.shtml.

One project recommendation—to develop reimbursement models that sustain and promote primary care practices—led to the formation of a sixth task force focused solely on enhancing practice reimbursement and finance issues. Task Force 6 is expected to report its findings and recommendations later in 2004.

A primary objective of the FFM project was to recommend changes to the discipline so that family medicine can better meet the health care needs of patients in a changing environment. Family physicians are relying on the FFM project to identify strategic directions that resonate across the discipline and with others seeking to improve health care and health. The report offers specific recommendations to help improve family physicians’ performance.

At the same time, family medicine cannot fully succeed, nor will the needs of the public be met, without fundamental changes in the US health care system. Americans are frustrated by a health care system that produces wondrous results for a few, but costs so much that even basic care is increasingly unaffordable for many; that promises the latest in science and technology, but delivers care that is fragmented, impersonal, or of inconsistent quality; that permits experimentation in health plan provisions and financial incentives, but does not learn from the resulting chaos and inequities.

This report is an attempt to stimulate and guide some initial steps toward a serious revision of family medicine and health care in the United States. It should not be interpreted as an explicit blueprint, but rather as a compass and a call to action for family physicians and others concerned with the specialty; a call to exert leadership in implementing a compelling vision for a better family medicine, stronger primary care, and an improved US health care system. It was the intent of the FFM project to be bold enough to inspire, but sufficiently practical and incremental as to present achievable next steps in a journey that began long ago and seems destined to continue for as long as human beings feel the need to seek the help of a trusted healer.

As a key initial step in the development of this report, a national research study was conducted by independent research firms. This effort produced a wealth of interesting, and in some cases provocative, quantitative, and qualitative findings. The FFM research data will be maintained at the Robert Graham Center: Policy Studies in Family Practice and Primary Care in Washington DC, and will be made available for future study and research. Additional background information, including the original task force reports, will be maintained in the Center for the History of Family Medicine in Leawood, Kan. The professional organizations of family medicine are encouraged to review these data critically and to make this information widely available to their individual constituents as a starting point for building consensus on the need to implement the recommendations of the FFM project.

This report reflects a vision of the role of the discipline of family medicine in the US health care system. The Project Leadership Committee sought outside research and external opinions, individually and in many public forums, and they specifically included persons outside the discipline of family medicine. Yet, the report reflects the experience, skills, strengths, and weaknesses of the individuals involved, including their interpretation of the invited input and available data. Nevertheless, the Project Leadership Committee believed the urgency of the situation required deriving conclusions and recommendations with current information.

It is an enormous task to retool the specialty and reform the health care system. The results of this project are highly dependent on the ensuing input, critique, and implementation by family physicians throughout the country, individuals within the public, policy makers, other health care professionals, and patients themselves. The Project Leadership Committee strongly desires further reflection and energetic discussion of both the conclusions and the recommendations. These ideas need to be tested and refined in practice. Of particular interest will be the response and assistance of those to be served by the New Model of family medicine.

INTRODUCTION

Nearly 4 decades ago, the specialty of family practice was created to fulfill the generalist function in medicine, which the American people wanted and which suffered with the growth of subspecialization after World War II. Although the specialty has delivered on its promise to reverse the decline of general practice1,2 and provide personal, frontline medical care to people of all socioeconomic strata and in all regions of the United States,3 all is not well either with family medicine or with health care in general.4–11

At the national level, serious health policy issues appear to be intractable. A large proportion of the population (at least 40 million people) lack health insurance,12 almost 20% of the population lacks a usual source of care,13,14 the public health infrastructure remains weak,15,16 and mental health care struggles for recognition and parity.17 Health care is highly fragmented rather than seamlessly integrated. There exists renewed uncertainty about the adequacy of the health care workforce,18–26 confirmation of important disparities in health and health care,27 alarm about medical errors in all health care settings,28,29 and concern about accelerating health care spending, with a return to double-digit price escalation in health insurance premiums during a period of economic slump.30,31 Personal stories of despair and forecasts of collapse of the health care system are frequent fare in the media.32–34

Concern and frustration among family physicians with the direction of health care in the United States did not arise overnight. The 1990s began with a spirit of optimism that managed care would actually manage care and organize a fragmented and wasteful system, with family physicians and other primary care clinicians having a defined and central role. Soon this optimism gave way to great frustration when, instead of integration of care in the context of a sustained partnership between patients and their personal physicians, new layers of administrative decision makers—with oftentimes conflicting objectives—appeared. In this new, suddenly less positive, practice environment, family physicians found themselves painted as gatekeepers standing between their patients and care rather than being able to serve their patients as gateways to appropriate care.

Treating health care as a commodity that could be bought and sold, with large blocks of insured patients being moved annually from health plan to health plan, from provider to provider, and from system of care to system of care, eroded trust as relationships were fractured repeatedly.35 Few family physicians lack patients, but for many their work has devolved from meaningful service grounded in rich, personal relationships into jobs designed to manufacture health care that too often neither heals nor relieves suffering.36 While medical expenditures have increased, net income for physicians has declined, more so for primary care physicians than for specialists.37

In 1996 the Institute of Medicine (IOM), through the Committee on the Future of Primary Care, concluded that the nation’s understanding of primary care was so poor, it was necessary to redefine it to establish a basis for study. The IOM definition clarified that primary care is not a discipline or specialty but a function as the essential foundation of a successful, sustainable health care system.38 Whereas many types of clinicians lay claims to providing primary care, the IOM concluded that the evidence pointed to family physicians, general internists, general pediatricians, and many nurse practitioners and physician assistants as the key primary care providers in the United States. That family physicians are key providers of primary care is indisputable; thus, family medicine and primary care are and will remain intertwined.39

The 1996 IOM report on primary care was prepared at a time when universal coverage and health care reform were anticipated on a national scale. Such was not to be, however, and the call for investment in primary care went largely unheeded. In the years since the issuance of that IOM report, the rate of growth in the subspecialty physician pool has continued to far exceed the rate of growth in family medicine and other primary care specialties. This disparity is reflected in the minimal growth in numbers of primary care physicians per 1,000 population compared with the growth experienced by non–primary-care specialists. Meanwhile, interest expressed by medical students in family medicine has declined to near crisis proportions,40 as reflected in the declining match rates into family medicine residency training programs.

As the 21st century began, a sustained focus by the IOM on the quality of health care in the United States culminated in widely received publications that provided ominous warnings regarding the overall state of US health care.28,41 The 2001 IOM report, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century41 (the Chasm Report) made the startling assertion that the US health care system was so flawed it could not be fixed and an overhaul was required. This landmark report articulated 6 aims suggesting that the 21st century health care system should be:

Safe—avoiding injuries to patients from the care that is intended to help them

Effective—providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit and refraining from providing services that will not likely benefit them

Patient-centered—providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions

Timely—reducing waits and sometimes harmful delays for both those who receive and those who give care

Efficient—avoiding waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy

Equitable—providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics, such as gender, race, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status

These aims were widely perceived to be valid and were embraced by many family physicians as being consistent with their purpose and their aspirations. The Chasm Report went further and proposed rules that could guide the redesign of health care away from a decaying and failing system toward a new system of which the United States could be proud (Table 1▶). These rules were yet another call to action that was consistent with the goals and natural inclinations of family physicians and others committed to robust primary care for the nation.

Table 1.

Simple Rules for the 21st Century Health Care System

| Current Approach | New Rule |

|---|---|

| Care is based primarily on visits | Care is based on continuous healing relationships |

| Professional autonomy drives variability | Care is customized according to patient needs and values |

| Professionals control care | The patient is the source of control |

| Information is a record | Knowledge is shared and information flows freely |

| Decision making is based on training and experience | Decision making is evidence-based |

| Do no harm is an individual responsibility | Safety is a system property |

| Secrecy is necessary | Transparency is necessary |

| The system reacts to needs | Needs are anticipated |

| Cost reduction is sought | Waste is continuously decreased |

| Preference is given to professional roles rather than the system | Cooperation among clinicians is a priority |

Source: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.41

The need for in-depth reevaluation and reform was not limited to the health system level. At the level of the discipline, family medicine was challenged by contradictions and tensions, including confusion about family medicine being a reform movement (a solution) or an incumbent medical specialty (a problem), questions regarding whether family physicians should be considered generalists or specialists, debate about family medicine being vital for all or an option for a few, concerns regarding the knowledge base underlying training in family medicine, and uncertainty about the intrinsic value of some of the services provided by family physicians.42

RESEARCH

In this context, the leaders of 7 national family medicine organizations agreed it was essential that family medicine be responsive to the needs of the public and that the discipline take the lead toward constructive change. In response, the sponsoring organizations convened a historic conference, called Keystone III, to “examine the soul of the discipline of family medicine—to take stock of the present and grapple with the future of family practice.”43 As a key preparatory step to the development of this report, the sponsoring organizations also chartered a national study conducted by independent researchers (Greenfield Consulting Group and Roper ASW), who worked collaboratively with a national strategic branding firm (Siegel & Gale). The goal of the FFM research effort was to develop an objective understanding of the contemporary situation of family medicine in the United States based on unbiased quantitative and qualitative research. A full description of the methods is available as supplemental data in Appendix 1, which can be found online at http://www.annfammed/org/cgi/content/full/2/suppl_1/S3/DC1.

The research effort was guided by the following questions:

What are people’s perceived health care needs and what are their perceptions about how family physicians can meet those needs?

Why, if at all, would people select and prefer family physicians as their primary physicians?

What, if anything, is distinct about family physicians?

Is there a group for which family medicine is irrelevant or makes no sense?

What are the most promising, but unrealized, opportunities for family medicine?

Do people desire the core attributes of family medicine (eg, first contact, continuity, community basis and context, comprehensiveness)?

What challenges must family medicine overcome to meet contemporary expectations of people?

The study contractors began with qualitative research involving 15 interviews with thought leaders in and outside family medicine; 5 focus groups with family physicians; 13 focus groups with patients (2 groups with patients who had a family physician, 4 groups with patients across the adult age ranges who did not have family physicians, 2 rural groups, 1 chronically ill group, 1 Hispanic group, 1 Asian group, 1 African-American group, and 1 inner-city group); 3 focus groups with medical subspecialists; 3 with managed care/payers; 2 with medical students; 2 with resident physicians; and 1 with nurse practitioners. A national probability sample of the public was then queried using standard methods, sampling 1,031 patients, 125 additional parents of children, 300 family physicians, 75 academic family physicians, 75 non–primary-care medical specialists, 100 medical students, and 150 residents in medical training. Further one-on-one interviews were conducted with family physicians, payers, advocacy groups, benefits managers, Medicare/Medicaid administrators, nurse practitioners, and patients.

The qualitative and quantitative research produced a wealth of findings,44 including the following:

Family physicians are not well recognized by the public for what they are and what they do. Patients have a hard time differentiating family medicine from other primary care physician specialties, notably not distinguishing clearly between family medicine and general internal medicine. Indeed, the words “family” and “practitioner” were often found to confuse people and suggested to some that family physicians lack scientific background and competence.

Patients want their primary care physician to meet the following 5 basic criteria: to be in their insurance plan, to be in a location that is convenient, to be able to schedule an appointment within a reasonable period of time, to have good communication skills, and to have a reasonable amount of experience in practice.

Beyond the basic criteria, patients value the relationship with their physician above all else, including service. Patients value a physician who listens to them, who takes time to explain things to them, and who is able to coordinate effectively their overall care.

There is some skepticism regarding the concept of a comprehensive care provider who treats a broad range of health care problems. At least in part this reaction is based on the belief that it is unrealistic to expect any one physician to be able to stay current and maintain competence in all areas of medicine.

Family physicians were rated as “excellent” or “very good” by a clear majority of survey respondents on the top 5 relationship-related attributes identified by patients: being nonjudgmental, understanding, and supportive; being honest and direct; acting as a partner in maintaining health; listening effectively; and attending to patients’ emotional and physical health.

Although patients rank relationship-based attributes most highly, there is a tension between the desire to have a primary physician who is able to treat many illnesses and who treats the patient as a whole person, with the perception that it is not possible for any one physician to be knowledgeable and skilled in all areas of medicine.

The American public is enamored with science and technology, and they want their physicians to be technologically savvy. The public, however, does not associate family physicians with science and technology.

Patients expect high-quality health care, but instead of using quality as a selection criterion for physicians, they often assume that it exists. Patients tend to judge health care on relationships and rate family physicians highly in this regard. Because patients value relationship so highly and assume the quality of their care is high, they may forgive many of the inadequate service aspects of their care.

Challenges and Opportunities for the Future

Based on an analysis of the findings on patient perceptions and expectations, along with research on the attitudes and perceptions of family physicians, medical students, subspecialists, family medicine residents, and residents in other specialties, 5 major challenges were identified that will influence family medicine’s future viability:

Promoting a broader, more accurate understanding of the specialty among the public

Identifying areas of commonality in a specialty whose strength is its wide scope and locally adapted practice types

Winning respect for the specialty in academic circles

Making family medicine a more attractive career option

Addressing the public’s perception that family medicine is not solidly grounded in science and technology

After reviewing the research findings and considering the implications of these 5 challenges, the FFM Project Leadership Committee concluded that unless there are changes in the broader health care system and within the specialty, the position of family medicine in the United States may be untenable in a 10- to 20-year time frame, which would be detrimental to the health of the American public. The FFM Project Leadership Committee further concluded that changes must occur within the specialty, as well as within the broader health care system, to ensure the ability of family medicine to meet these challenges and continue to fulfill its unique mission and role. These conclusions confirmed the importance of developing an FFM action plan to ensure the continued relevance and viability of the specialty.

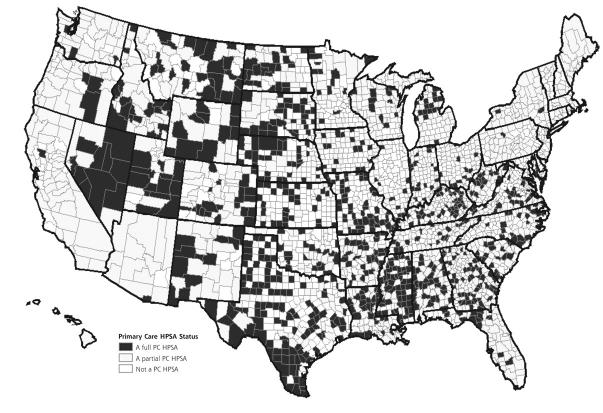

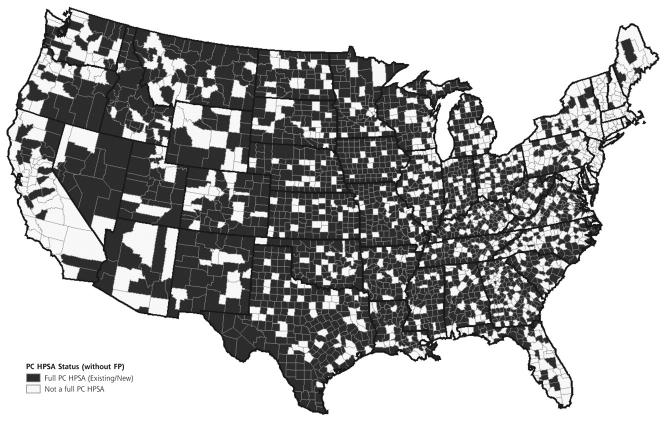

Considerable evidence supports the contemporary importance of family physicians in the US health care system. For example, care by generalists uses few resources while producing similar health outcomes for patients with chronic disease.45,46 Many counties would become shortage areas without their family physicians (Figures 1▶ and 2▶). Looking internationally, countries that emphasize primary care have better population health at lower cost.39 It is not surprising that the World Health Organization calls for an increased presence of primary health care in order to support progress in health.47

Figure 1.

1999 distribution of counties with full or partial primary care health personnel shortage designation.

PC = primary care; HPSA = health professional shortage area.

Source: The Robert Gaham Center: Policy Studies in Family Practice and Primary Care.

Figure 2.

1999 distribution of counties with full or partial primary care health personnel shortage designation without family physicians.

PC = primary care; FP = family physicians; HPSA = health professional shortage area.

Source: The Robert Gaham Center: Policy Studies in Family Practice and Primary Care.

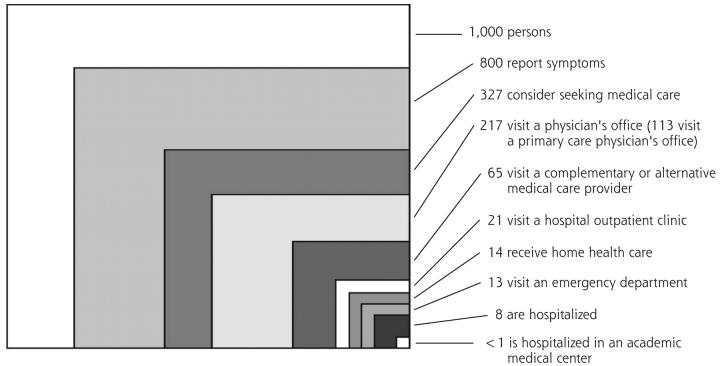

In addition, as Figure 3▶48 illustrates, more people receive formal health care in physicians’ offices—particularly primary care physicians’ offices—than any other location; indeed, in an average month 14 times more people receive care in a primary care physician’s office than hospital inpatients. Furthermore, people beset with the nation’s high-priority health problems rely primarily on family physicians and general internists as their usual source of care (Table 2▶).49 Indeed, the latest nationally representative data confirm that family medicine continues to be the medical specialty providing more office visits (199 million) than any other specialty.50

Figure 3.

The ecology of medical care revisited.

Note: All numbers refer to discrete individual persons and whether or not they received care in each setting in a typical month.

From: Green LA, Fryer GE Jr, Yawn BP, Lanier D, Dovey SM. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:2021–2025.48 Reprinted with permission from the Massachusetts Medical Society.

Table 2.

Distribution by Specialty of the Usual Source of Care for People With Selected Conditions and a Physician as That Usual Source

| Condition | Family Medicine % | General Internal Medicine % | General Pediatrics % | All Others % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease | 56 | 31 | 0.0 | 14 |

| Stroke | 56 | 34 | 0.9 | 9 |

| Hypertension | 63 | 28 | 0.2 | 8 |

| Diabetes | 67 | 23 | 0.6 | 10 |

| Cancer | 60 | 26 | 2.3 | 11 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 62 | 22 | 5.4 | 11 |

| Asthma | 58 | 15 | 20.8 | 6 |

| Anxiety/depression | 62 | 20 | 7.0 | 11 |

Note: Data are based on 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys.

Despite these seemingly positive indicators of the importance of family medicine, there are a number of disturbing trends. For example, the proportion of visits to family physicians for acute, chronic, and preventive care has been in slow decline overall. Also, there was a steady and progressing decline from 1980 through 1999 in the percentage of US physicians who were family physicians.51

After analyzing all of these data and trends—both positive and negative—the FFM Project Leadership Committee concluded that family medicine continues to meet a fundamental public need for integrated, relationship-centered health care52 and that the problems afflicting family medicine do not include irrelevance or obsolescence. Functioning within a health care system that is broadly viewed as flawed and failing, family medicine nevertheless finds many of its core attributes highly sought after by the American public. The future contributions and well-being of the discipline lie, in part, in the ability of family medicine to rearticulate its vision and competencies in a fashion that has greater resonance with the public, while at the same time substantially revising the organization and processes by which care is delivered.

Even within the constraints of the current flawed health care system, there are great opportunities for family physicians to redesign their models of practice to better serve patients while achieving greater economic success. In fact, because major elements of the US health care system are in disarray, a climate exists in which the reconfiguration and reengineering of the basic elements of office-based family medicine may meet less resistance than would be the case in a system more generally viewed as performing adequately. To realize fully the aspirations of the discipline, however, there must be major changes in the organization and financing of health care services in the United States as well as within the specialty itself.

FOUNDATION FOR A REINVIGORATED DISCIPLINE

In preparing to move the specialty of family medicine forward, it is important first to articulate the core values, the key characteristics, and the identity that provide the foundation for family medicine and position the specialty favorably to address the challenges and opportunities of the future.

Core Values

The development of family medicine and its identity as a discipline has been grounded in the core values of continuing, comprehensive, compassionate, and personal care provided within the context of family and community. These core values of family medicine are responsible for much that the public currently values and trusts in family physicians. They have shaped the identity of individual family physicians and contributed to establishing a legitimate position for family physicians in academia and in the larger medical community.53,54 A challenge to the specialty is to articulate these core values in a sufficiently distinctive way so they are recognized by the public as central to what patients seek from their personal physician. To date, family medicine has not done an adequate job of communicating its core values to the public.

Family physicians are committed to continuing, comprehensive, compassionate, and personal care for their patients. They are concerned with the care of people of all ages, and understand that health and disease involve the mind, body, and spirit and depend in part on the context of patients’ lives as members of their family and community.38,52,55 These core values are congruent with the IOM aims and rules for the 21st century health care system and likely are essential to their realization.

To achieve top performance, family physicians must work in practice environments that fully promote these transforming values. They must practice on a daily basis scientific, evidence-based, patient-centered care; they must accept a measure of responsibility for the appropriate and wise use of resources; and they must work in teams within and beyond their practice setting, focusing on the integration of care for each of their patients. Success in these endeavors requires systems that enhance quality by maintaining access to comprehensive, compassionate, personalized care while reducing unwanted variability in diagnosis and treatment by reducing errors of misuse, overuse, and underuse and by measuring results for individuals and populations under their care.39,41

Building on these core values, the Project Leadership Committee identified the following functions of a family physician: a family physician offers continuing, comprehensive, compassionate, and personal health care in the context of family and community. At the core of the specialty is the concept of integration of health care for patients of both sexes across the full spectrum of ages in the context of a continuing relationship. Family physicians have skills in diagnosing and treating illness, in performing diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, and in managing relationships, information, and processes. The care provided by family physicians is based on evidence and is outcome oriented. Family physicians are actively involved in the pursuit of new knowledge that will increase understanding of health and illness and improve the delivery of health care.

Key Characteristics and Identity

Building on the 5 key characteristics of family physicians that were identified through the study (Table 3▶),44 the Siegel & Gale consultants proposed the following identity statement for family physicians: family physicians are driven by the need to help make people whole by humanizing medicine. After considerable discussion over many months, the Project Leadership Committee adopted the following identity statement, which incorporates key concepts integral to the identity of family physicians, including a commitment to fostering health, an orientation toward integrating health care for the whole person, a talent for humanizing medicine, and a dedication to providing science-based high-quality care:

Table 3.

Key Attributes of Family Physicians

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| A deep understanding of the dynamics of the whole person | This approach leads family physicians to consider all the influences on a person’s health. It helps to integrate rather than fragment care, involving people in the prevention of illness and the care of their problems, diseases, and injuries |

| A generative impact on patients’ lives | This terminology comes from Erik Erikson’s work on personality development. Family physicians participate in the birth, growth, and death of their patients and want to make a difference in their lives. While providing services that prevent or treat disease, family physicians foster personal growth in individuals and help with behavior change that may lead to better health and a greater sense of well-being |

| A talent for humanizing the health care experience | The intimate relationships family physicians develop with many of their patients over time enable family physicians to connect with people. This ability to connect in a human way with patients allows family physicians to explain complex medical issues in ways that their patients can understand. Family physicians take into account the culture and values of their patients, while helping them get the best care possible |

| A natural command of complexity | Family physicians are comfortable with uncertainty and complexity. They are trained to be inclusive, to consider all the factors that lead to health and well-being—not just pills and procedures |

| A commitment to multidimensional accessibility | Family physicians are not only physically accessible to patients and their families and friends, they are also able to maintain open, honest and sharing communications with all who are involved in the care process |

Family physicians are committed to fostering health and integrating health care for the whole person by humanizing medicine and providing science-based high-quality care.

Exactly how these characteristics are stated is less important than a recognition of their contemporary importance and that they enhance the core values of family physicians the public finds attractive and valuable. These key attributes and core values are what characterize family physicians (Table 3▶).

The public is hungry for these attributes as the current health care system becomes increasingly fragmented and impersonal.44,56–59 To realize fully the potential of the specialty and to meet completely the needs of patients, however, changes are needed in the following 3 broad areas: (1) clinical practice, or how family physicians’ medical practices are organized and function; (2) medical education, or how family physicians are trained and how they maintain and update their knowledge and skills throughout their careers; and (3) health system, or how the US health care system is organized and financed.

BRINGING ABOUT CHANGES IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Reintegration of Patient, Physician, and Practice Through a New Model

The current shortcomings and dissatisfaction with the US health care system provide family physicians with a compelling opportunity to improve the health of the nation and shape their own destinies by redesigning their model of practice. The 6 aims and 10 new rules identified in the IOM Chasm Report, along with the key characteristics and identity statement for family medicine developed as part of this study, point the way to a proposed new model of practice for family medicine (New Model) that is traditional enough to reflect and sustain enduring principles and values, familiar enough to be understandable, bold enough to attract interest and funding, and practical enough to be implemented in the immediate future.

A number of the elements of the New Model may seem familiar to and even part of the practices of many family physicians. What makes the model new is that it is centered primarily and explicitly on the needs of the patient, it incorporates new concepts from industrial engineering and customer service, and it integrates these needs and concepts into a coherent and comprehensive approach to care. Although some family physicians have incorporated one or more of the characteristics of the New Model into their practices, few, if any, have designed practices that integrate all of these elements.

The critical bridge between the expression of the core values of family medicine as a medical discipline and the New Model of care, in which the family physician’s patients will be cared for, is the relationship between the physician, the practice, and the patient. The family physician’s commitment to fostering health and integrating health care has major implications for the redesign of the specialty of family medicine. The challenge is one of configuring family medicine in such a way that patients will feel not only cared for but also guided appropriately through and represented within the larger health care system. Meeting this challenge will require a reintegration of the patient, the practice, and other providers and organizations in the context of the community and, ultimately, the larger health care system.60 Only through such a reintegration will safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable care be possible.

For family medicine to contribute substantially to this reintegration, family physicians will need to reconceptualize their role and redesign their practices accordingly. Looking to the future, family physicians must not only have the requisite skills in diagnosis, treatment, and performance of procedures, they must also demonstrate competencies in managing relationships, information, and processes.61–63

Managing Relationships

Because a continuous healing relationship is the essence of care, family physicians must be able to develop and sustain partnerships with patients over time, establish and maintain systems and procedures that support those relationships, and enable timely access to the services their patients need.

Managing Information

The complexity of caring for patients with acute and chronic problems over time and managing preventive services for populations of patients requires the involvement of many health care professionals working in well-organized systems and supported by information technology.64 It requires partnering with patients. Family physicians will rely increasingly on information systems and electronic health records to provide assessments, checklists, protocols, and access to patient education and clinical support. Clinical information must be maintained in a format that allows for ready search, retrieval, and information transfer while protecting the privacy and confidentiality of patients’ medical records. Having electronic health records with a relational database design and meeting national technical standards are essential. The paper medical record can no longer provide a sufficient foundation for clinical care and research within family medicine.

Managing Processes

All clinicians work in systems of care. Some family physicians work in small systems; others work in extremely large systems. Family physicians and their health professional colleagues must assume responsibility for the constant assessment and improvement of their care. Patients, the central focus of the family physician’s clinical enterprise, are crucial participants in many of the processes of care and must share responsibility for receiving appropriate and successful care. Working together on behalf of patients requires teamwork that occurs within a complex set of relationships and services. It requires skillful management with appropriate authority and collaboration as well as a mindset of vigilance and continuous process improvement.38 Table 4▶38,41,65–68 summarizes the orientation and characteristics that New Model practices will need to embrace.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the New Model of Family Medicine

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Personal medical home | The practice serves as a personal medical home for each patient, ensuring access to comprehensive, integrated care through an ongoing relationship |

| Patient-centered care | Patients are active participants in their health and health care. The practice has a patient-centered, relationship-oriented culture that emphasizes the importance of meeting patients’ needs, reaffirming that the fundamental basis for health care is “people taking care of people”65 |

| Team approach | An understanding that health care is not delivered by an individual, but rather by a system,66 which implies a multidisciplinary team approach for delivering and continually improving care for an identified population41,67 |

| Elimination of barriers to access | Elimination, to the extent possible, of barriers to access by patients through implementation of open scheduling, expanded office hours, and additional, convenient options for communication between patients and practice staff |

| Advanced information systems | The ability to use an information system to deliver and improve care, to provide effective practice administration, to communicate with patients, to network with other practices, and to monitor the health of the community.68 A standardized electronic health record (EHR), adapted to the specific needs of family physicians, constitutes the central nervous system of the practice |

| Redesigned offices | Offices should be redesigned to meet changing patient needs and expectations, to accommodate innovative work processes, and to ensure convenience, comfort, and efficiency for patients and clinicians |

| Whole-person orientation | A visible commitment to integrated, whole-person care through such mechanisms as developing cooperative alliances with services or organizations that extend beyond the practice setting, but which are essential for meeting the complete range of needs for a given patient population.38 The practice has the ability to help guide a patient through the health care system by integrating care—not simply coordinating it |

| Care provided within a community context | A culturally sensitive, community-oriented, population-perspective focus |

| Emphasis on quality and safety | Systems are in place for the ongoing assessment of performance and outcomes and for implementation of appropriate changes to enhance quality and safety |

| Enhanced practice finance | Improved practice margins are achieved through enhanced operating efficiencies and new revenue streams |

| Commitment to provide family medicine’s basket of services | A commitment to provide patients with family medicine’s full basket of services—either directly or indirectly through established relationships with other clinicians |

Two important points should be kept in mind in reviewing the characteristics of New Model practices. First, changes to current health care payment mechanisms that promote more equitable reimbursement will be necessary for some of the benefits of the New Model to be realized fully. Many aspects of the New Model, however, can be implemented independent of reimbursement reform. Second, although some of the New Model characteristics have been implemented on a piecemeal basis by innovative family physicians, it is the entire spectrum of characteristics that represents the change in orientation from the traditional model of family medicine to the New Model.

Personal Medical Home

In addition to the changes that family physicians can implement to enhance patient access to care, steps must be taken to ensure every American has a personal medical home* that serves as the focal point through which all individuals—regardless of age, sex, race, or socioeconomic status—receive a basket of acute, chronic, and preventive medical care services. Through their medical home, patients can be assured of care that is not only accessible but also accountable, comprehensive, integrated, patient-centered, safe, scientifically valid, and satisfying to both patients and their physicians.

Patient-Centered Care

The cornerstone of the New Model is patient-centered care based on a patient-physician relationship that is highly satisfying and humanizing to the patient and the physician (as well as other practice clinicians). The starting place for helping to foster health and integrate health care will be to establish a culture within each family medicine setting. In the New Model, the patient, not the physician, occupies center stage. From first contact through the completion of the care episode, the patient must meet with consistent and competent care. In the New Model, all patients will receive care that is culturally and linguistically appropriate.

New Model practices strive to meet patient and community needs for integrated care by giving patients what they want and need—including preventive care, acute care, rehabilitative care, chronic illness care, and supportive care—when they want and need it by anticipating patient needs and designing services to meet those needs.

Whole-Person Orientation

The focus of New Model practices will be comprehensive, integrative care designed to meet the complete range of needs of the community served by the practice.37 Although patients are ultimately responsible for their health, the family physician in a New Model practice will conceive of himself or herself as the chief consultant and advisor for each patient’s health care. The practice will provide or integrate all of their patients’ care. Family physicians will consider not only what they can do for their patients but also what other resources and services are available in the community to meet patient needs. When a family physician cannot provide specific services personally, he or she will refer patients to the appropriate source of care for their particular needs.

The New Model practice will continue to provide care for both sexes, across all ages, socioeconomic classes, and settings. Accepting the complexity of health and health care, the New Model practice will provide multiple ways for patients to access care and will ensure optimal care to people regardless of socioeconomic status. Such a practice will be a system that models the very whole-person orientation that patients can expect in the care they receive. Although the office setting will continue to be an important site for care, it is important to emphasize that to integrate patient care effectively, future family physicians will need to be prepared to provide services in a variety of settings, including hospitals and long-term care facilities; in short, they will provide care wherever the family physician’s services are needed by patients.

Team Approach

Patient care in the New Model will be provided through a multidisciplinary team approach and grounded in a thorough understanding of the population served by the practice. In addition to nurses and clerical personnel, staffing will often include physician assistants and nurse practitioners as well as nutritionists, health educators, behavioral scientists, and other professional and lay partners. Some of these staff may work in the practice only on a part-time basis. Depending on the particular circumstances, patients may receive care from any one of several members of the multidisciplinary team rather than from a family physician.

A cooperative effort among all clinicians will be the cultural norm, and it will be understood that the practice is more than the sum of its individual parts. Practice staff will share in decision making regarding patient care with explicit accountability for their performance to patients, to each other, and to each patient’s personal physician. Systems of care will be honored and supported. New Model practices will develop collaborative relationships with sub-specialists for the purposes of improving and better integrating patient care. In some cases, subspecialists may see patients on-site at New Model practice facilities.

Elimination of Barriers to Access

Under the New Model, barriers to patient access will be minimized. Practices will use an open scheduling model for patient visits (ie, the patient usually will be able to make an appointment for the same day, regardless of the type of problem or visit required), while offering flexible and expanded office hours. The practice will provide a convenient mechanism for asynchronous communication for nonurgent issues (eg, voice mail and e-mail), as well as telephone communication with a person—not an answering machine or voice mail—24 hours a day, 7 days a week for urgent matters. In areas where multiple practices exist, New Model practices will be networked for providing urgent services on site in one practice when other practices are closed, with communication links in place to assure seamless communication to the patient’s physician regarding the urgent care provided.

Interactions will not be limited to traditional, individual, face-to-face encounters between the patient and the family physician. Where feasible and as systems evolve, New Model practices will develop a Web portal and will use secure e-mail to provide additional, convenient options for communication between patients and practice staff. Patients will be able to make appointments online through the practice Web site and will be able to access online patient education materials appropriate to their health status.

Information Systems

A standardized electronic health record, adapted to the specific needs of family physicians and the patients they serve, will constitute the central nervous system of the New Model practice. However the electronic health record is structured, high priority must be given to assuring that information from multiple, diverse sources (hospital, office, long-term care facility, etc) is integrated into a single system to support the comprehensive information needs on which primary care practices depend. Similarly, electronic health record systems must permit the collection, analysis, and reporting of the clinical decisions and their outcomes that primary care clinicians make every day. The system should provide an informatics infrastructure that supports practice-based research, quality improvement, and the generation of new knowledge.

This electronic information system must integrate easily into the daily practice of family physicians, must be accessible at reasonable cost, and must result in a major enhancement to the efficiency and quality of the care that is delivered. As a replacement for or an important adjunct to traditional record keeping, the system must be user friendly, flexible enough to integrate a variety of management tasks, stable and reliable, and delivered with appropriate training for physicians with highly variable levels of comfort and experience with such systems.

The information system for the New Model practice should be based on common health information technology standards, should be interoperable across all levels of care, and should be capable of collecting a wide range of demographic information about the patient population. The system should contain an up-to-date and accurate problem and medications list for each patient and information about each patient encounter. It also should have an export function that is capable of sharing data elements in a standardized format so they can be analyzed in conjunction with data from other practices to create quality parameters and assessment measures.

The information systems of New Model will facilitate the integration of the care of the whole person in the context of their family and community. These systems will also include evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for enhancing the care of those individual conditions most commonly encountered by family physicians. They will have an order entry and referral tracking system, a managed care organization-specific pharmacy formulary, and Web-enabled access to data repositories, with appropriate levels of security.

Furthermore, information systems of the New Model practice will be able to generate chronic disease registries, which will ensure that patients can be recalled for care at appropriate time intervals, and able to track health maintenance interventions and generate physician and patient reminders for personalized preventive services. It will be integrated with common practice management and billing systems; have some availability to patients by means of a Web interface for entry of self-care data, patient history data, health-related quality-of-life measures, mental health screening questionnaires, and other applications; and be able to support practice-based clinical research using electronic audits concerning the costs, processes, and outcomes of care (including the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set or similar measures).

In addition to the electronic health record, the New Model practice will have computerized decision support systems—ideally Web based—to help patients make better, more informed health care decisions and to facilitate the process through which the family physician explains patient care options. In addition, just-in-time information systems for physicians will allow rapid retrieval of best, up-to-date evidence at the point of care. This system will be sufficiently standardized to allow access upon written release when patients require care away from their personal medical home.

Redesigned Offices

New Model practice facilities will be designed to accommodate staffing patterns that differ from the current model, including most notably a broader array of health professionals working together as part of a multidisciplinary team. Family medicine offices will be designed specifically to meet the needs and expectations of the local community. Offices will be convenient, attractive, and functional and will have private, comfortable space to accommodate group visits with selected patients who share common health concerns.

The traditional waiting room will be a thing of the past, replaced by a patient resource center with a patient library, computer work stations with ready access to online health education materials, and patient information-gathering stations. Practices will be equipped with sufficient technology, staff, and supplies to be able to provide on-site a comprehensive set of diagnostic services, testing for important genetic predispositions, and performance of common therapeutic procedures.

Focus on Quality and Safety

The New Model practice will seek to improve continuously the quality of patient care. Practices will document quality and safety through ongoing analyses of practice patient care data. Patient feedback will be solicited to ensure that the practice is meeting patients’ expectations, satisfying their needs for access to the practice, and responding to the needs of increasingly diverse populations. Each practice will develop and use a structured, recurring administrative mechanism to examine the measurements of the practice and the patients under care. Practice staff, along with representative patients, will be included in these quality improvement processes. New Model practices will place a high priority on taking steps to ensure patients’ safety within the practice, including use of electronic data and decision support systems.

Enhanced Practice Finance

While vigorous efforts are pursued to secure equitable reimbursement for the services provided by family physicians, the dictum “no margin, no mission” will be taken seriously within New Model practices. Improved operating efficiencies will decrease practice expenses and contribute to improved practice margins. Practices will compete for gaining a portion of patients’ discretionary health care spending. New Model practices will be organized to accommodate all payment options while advocating for health insurance coverage of all Americans.

The Basket of Services in the New Model

The New Model practice will commit to providing the full basket of clinical services offered by family medicine* (Table 5▶), either directly through its own clinicians or indirectly through established, ongoing relationships with experienced clinicians outside the practice. Even if the practice does not have the expertise or interest to provide directly a particular type of care within the basket of services, the patient nevertheless will be assured of receiving that care and having that care effectively coordinated and integrated.

Table 5.

Basket of Services in the New Model of Family Medicine

| Health care provided to children and adults |

| Integration of personal health care (coordinate and facilitate care) |

| Health assessment (evaluate health and risk status) |

| Disease prevention (early detection of asymptomatic disease) |

| Health promotion (primary prevention and health behavior/lifestyle modification) |

| Patient education and support for self-care |

| Diagnosis and management of acute injuries and illnesses |

| Diagnosis and management of chronic diseases |

| Supportive care, including end-of-life care |

| Maternity care; hospital care |

| Primary mental health care |

| Consultation and referral services as necessary |

| Advocacy for the patient within the health care system |

| Quality improvement and practice-based research |

The basket of services that patients can be assured of receiving through a New Model practice will include the management and prevention of acute injuries and illnesses, chronic diseases, health promotion, well-child care, child development and anticipatory guidance services, and rehabilitation and supportive care across health care settings. State-of-the-art chronic disease management will be an important part of the services provided by New Model practices. The care of patients with chronic diseases will utilize a community population-based approach, including the use of disease registries and community-oriented primary care methods. The practice will adhere to evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, which will be embedded into the electronic health record, and will participate in continuous quality improvement and practice-based research. The management of patients with chronic diseases will involve the full multidisciplinary team and will include some care of patients in their homes. The use of telemedicine and other new technologies will be explored as ways of enhancing the management of these patients.

The New Model office will put into practice the most current public health concepts and strategies while providing excellent preventive care across the individual life cycle and age spectrum. Preventive interventions will be implemented based on the quality of supportive evidence. Standard and personalized health risk assessments will be utilized for risk factor identification. The electronic health record will play a key role in tracking adherence to prevention guidelines and in continuously improving the quality of the preventive care provided by the practice. Health behavior and lifestyle modification skills will be essential to the multidisciplinary team providing preventive care in the practice.

Family physicians will participate in the care of their hospitalized patients. Depending upon local circumstances, they might not always assume full or primary responsibility for patient care in the inpatient setting. In all cases, though, there will be seamless transitions between different settings of care, and the approach taken to hospital care will support the maintenance of continuing, healing relationships with patients.

The flexibility and adaptability of the New Model will accommodate variation from practice to practice in the specific services provided, depending on the geographic location of the practice, the unique needs of the community being served, the physicians’ interests and training, and the availability of staff. For example, practices will vary in the range of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures performed, in the amount and intensity of hospital care provided, and in the extent to which they provide intrapartum maternity care. All family physicians, however, will share a common commitment to provide or coordinate all care specified in the family physician’s basket of services, thereby serving as effective personal medical homes for their patients.

Table 6▶ presents a simple comparison between the traditional model of practice and the New Model.

Table 6.

Comparison of Traditional vs New Model Practices

| Traditional Model of Practice | New Model of Practice |

|---|---|

| Systems often disrupt the patient-physician relationship | Systems support continuous healing relationships |

| Care is provided to both sexes and all ages; includes all stages of the individual and family life cycles in continuous, healing relationships | Care is provided to both sexes and all ages; includes all stages of the individual and family life cycles in continuous, healing relationships |

| Physician is center stage | Patient is center stage |

| Unnecessary barriers to access by patients | Open access by patients |

| Care is mostly reactive | Care is both responsive and prospective |

| Care is often fragmented | Care is integrated |

| Paper medical record | Electronic health record |

| Unpredictable package of services is offered | Commitment to providing directly and/or coordinating a defined basket of services |

| Individual patient oriented | Individual and community oriented |

| Communication with practice is synchronous (in person or by telephone) | Communication with the practice is both synchronous and asynchronous (e-mail, Web portal, voice mail) |

| Quality and safety of care are assumed | Processes are in place for ongoing measurement and improvement of quality and safety |

| Physician is the main source of care | Multidisciplinary team is the source of care |

| Individual physician-patient visits | Individual and group visits involving several patients and members of the health care team |

| Consumes knowledge | Generates new knowledge through practice-based research |

| Experience based | Evidence based |

| Haphazard chronic disease management | Purposeful, organized chronic disease management |

| Struggles financially, undercapitalized | Positive financial margin, adequately capitalized |

BRINGING ABOUT CHANGES IN TRAINING AND CONTINUING DEVELOPMENT

Graduate Medical Education

Unlike many other specialties, family medicine is not defined by a specific disease, organ or body system, by the age or sex of the patient population served, or by the setting in which care is provided. Rather, the family physician’s knowledge, skills, and attitudes encompass all ages, both sexes, a myriad of complaints and illnesses, and multiple settings. As such, the education of the family physician is one that emphasizes a process: the patient-physician relationship and problem definition/prioritization. The family physician is an expert in this approach.

Family medicine residency education began with a number of innovations more than 30 years ago, changes that have influenced residency education in other specialties. Its full potential has not yet been realized, however. The following changes in both the practice environment and in residency education since the specialty was created have resulted in a need to reevaluate and revise the traditional family medicine training model: few residency graduates now go into solo practice, only about one third include maternity care in their scope of services, and some provide little or no inpatient care.69 In addition, evidence-based, quality- and outcome-oriented medicine are driving forces today as opposed to being mere concepts 3 decades ago.

Given these and other changes, it is clear that the traditional family medicine curriculum, although successful in the past, will be challenged to meet the anticipated needs of the health care system of the future. Family medicine, at both the residency and medical school levels, must refocus and create models that support future needs by educating family physicians whose core knowledge, skills, and attitudes have been measured and whose special interests and competencies have been developed and locally adapted to a level of unquestioned excellence.

The core experience responsible for the formation of the family physician is residency training; therefore, the training of future family physicians will require a culture of innovation and experimentation to identify and evaluate new educational approaches. Family physicians of tomorrow will need to have knowledge, skills, and attitudes that go beyond diagnosis and treatment of disease, including skills in health promotion designed to maximize each patient’s potential. In addition, the family physician of the future will need to be an expert manager of knowledge, relationships, and processes.

In keeping with the FFM research findings, the results of other recent studies, and the mission of the FFM project, it is clear the training of future family physicians must be grounded in evidence-based medicine that is relevant to the care of the whole person in a relationship and community context. It also must be technologically up to date, built on a solid foundation of clinical science, and strong in the components of interpersonal and behavioral skills including cultural competency. Family medicine educators must be able to assure the public and other constituents that graduates of family medicine residency programs are qualified and competent to provide the full basket of services. Family physicians will continue to face challenges in health care, but they must learn to adapt, to be truly capable lifelong learners, to use new innovations and advances to further patient well-being, and to interact skillfully with every sector of the health care community.

Curriculum Changes

The family medicine residency curriculum has evolved substantially during the past 3 decades to meet the changing health care needs of the nation and to better prepare family physicians to deliver the kind of comprehensive, compassionate, and relationship-based care the public desires. Most curricular elements presently incorporated in family medicine graduate medical education remain pertinent and necessary. Some curricular elements, however, must evolve to remain relevant in a changing environment, new elements must be added to address emerging needs, and new knowledge of educational content delivery and assessment must be incorporated. In addition, longitudinal training elements need to be furthered.

Family physicians must continue to be broadly trained and have the competencies required to provide culturally effective and proficient care in a variety of settings. Specifically, family medicine residency programs must include training in community and population health, maternity care, and the care of hospitalized patients. Although it is important that maternity care continues to be included in the family medicine residency curriculum, training programs must be allowed to tailor that curriculum to be compatible with educational resources and anticipated practices. For example, the Residency Assistance Program criteria for excellence, approved in January 2003, describe 3 levels of maternity care curricula that address differing resources and needs. Similarly, although the care of hospitalized patients must remain an essential component of family medicine residency training, and all family medicine residency graduates must be able to demonstrate competencies in the care of inpatients, some programs might provide more extensive preparation than others.

Vision and Mission for Family Medicine Residency Education

The recent IOM report, Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality,70 concludes that health professions education has not kept pace with “changes in patient demographics, patient desires, changing health system expectations, evolving practice requirements and staffing arrangements, new information, a focus on improving quality, or new technologies.” The report calls for a new, overarching vision for all health professions education and proposes the following 5 competency areas as the foundation of education: (1) patient-centered care, (2) interdisciplinary team work, (3) evidence-based practice, (4) quality improvement, and (5) informatics. These attributes are central to the new vision of family medicine education. Building on the concepts in the IOM report on health professions education, the vision and mission for family medicine residency education can be stated as follows:

The vision for family medicine residency education is to transform family medicine residency education into an outcome-oriented experience that prepares and develops the family physician of the future to deliver, renew, and function within the New Model of practice and to deliver the best possible care to the American population.

The mission for family medicine residency education is to create a flexible model that trains family physicians to deliver patient-centered care consistently and lead an interdisciplinary team, emphasizing the biopsychosocial model, cultural proficiency, evidence-based practice, quality improvement, informatics, and practice-based research.

Educational Guidelines

As a visible demonstration of a commitment to these aims and rules, family medicine educators will need to translate them into guidelines for patient care within the medical education system.

Changes in the structure and content of residency programs should be made, as appropriate, to further the goals and values articulated above. Suggested program guidelines include flexibility and responsiveness, innovation and active experimentation, consistency and reliability, individualized to learners’ needs and the needs of communities. Program guidelines should also support critical thinking, competency-based education, scholarship and practice-based learning, integration of knowledge, medical informatics, biopsychosocial integration, professionalism, and collaboration and interdisciplinary approaches to learning (Table 7▶). For example, the discipline should actively experiment with 4-year residency programs that include additional training to add value to the role of family medicine graduates in the community.

Table 7.

Suggested Program Guidelines to Further the Vision and Mission of Family Medicine Resident Education

| Guideline | Description |

|---|---|

| Flexibility/responsiveness | Ability to provide education in areas needed to meet geographical and community needs |

| Innovation/active experimentation | Programs encouraged to try new methods of education, including 4-year curriculum pilot programs, and to teach the cutting edge of evidence-based medical knowledge |

| Consistency/reliability | Programs provide a basic core of knowledge and produce family physicians who exemplify the values of the health care system articulated by the Institute of Medicine |

| Individualized to learners’ needs and the needs of the communities in which they plan to serve | Programs offer enhanced educational opportunities in areas needed by graduates, such as maternity care, orthopedics, and emergency care |

| Supportive of critical thinking | Programs encourage and/or require research and expect a thorough understanding of evidence-based medical practice |

| Competency-based education | Programs stress a new paradigm for evaluation of resident performance based on competency assessments |

| Scholarship- and practice-based learning | Programs integrate scholarship and quality improvement through analysis and interventions built around patient care activities in the continuity setting |

| Integration of evidence-based and patient-centered knowledge | Programs model knowledge acquisition and processing from both perspectives in the patient care setting |

| Medical informatics | Programs go beyond just using an electronic health record (EHR) to modeling the broad-based acquisition, processing, and documentation potential within state-of-the-art informatics resources |

| Biopsychosocial integration | An emphasis on the interdependence and interplay among different levels of the system—whether it is the cardiovascular system, the individual, the family, the community, or the larger social context |

| Professionalism | Programs move beyond the simple objectives of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education professionalism curriculum requirements into a comprehensive monitoring and feedback system to residents during the critical developmental period of residency training |

| Collaborative and interdisciplinary approaches to all learning | Programs provide both support and role modeling for the effective use of teams and interdisciplinary approaches to patient care, including the involvement of other trainees in the process |

In addition to the above educational guidelines, residency training programs will need to take into consideration several factors.

As health care becomes more complex and medical care becomes more interdependent with other health care services, family physicians of the future will need to be experts at integrating all aspects of care. Given the commitment in family medicine to a biopsychosocial model of care, family physicians will have a special role in promoting better integration of medical and mental health services.

Family physicians will need to learn to work in teams and promote interdisciplinary collaboration in patient care, research, and education. To do so will require special skills in the areas of teamwork, collaboration, organizational management, and leadership.

With growing emphasis on cost resource management and systems-based care, family physicians of the future increasingly will be expected to be adept at weighing population-based and public health considerations in their medical decision making.

The ongoing development of the specialty and its need to contribute more substantially to the body of medical and health systems knowledge will depend on the growth of research and a greater commitment to a culture of ongoing inquiry in family medicine, both in academic and community settings.

To run the family medicine practice of the future efficiently, while adapting to a changing practice environment and striving to deliver optimal patient and population-based care, family physicians will need more in-depth training in practice management, particularly involving electronic health records and other information system applications.

Rearticulating and Redefining the Commitment of Family Medicine to Community and Family