Abstract

This article characterizes the large research domain of family medicine. It is a domain that can be productively explored from different perspectives, including: (1) the ecology of medical care and its focus on the environments of health care and interactions among them; (2) the realm of causation and important opportunities to discover how people lose and regain their health; (3) knowing medicine in different ways, focusing on what things mean in the inner and outer realities of individuals and groups of individuals; (4) the nature of the work of family physicians, such as first-contact care for any type of problem, sticking with patients regardless of their diagnoses, incorporating context into decision making, development of relevant technologies, articulating useful theory, and measuring what happens in family medicine; (5) the standard research categories of basic, clinical, health services, health policy, and educational research; and (6) thinking of family medicine research as both a linear process of translation and a wheel of knowledge with iterative loops of discovery that come from within family medicine. The domain of family medicine research is important and ripe for fuller discovery, and it invites the thinking and imagination of the best investigators. It seems unlikely that medical research can ever be complete without a robust family medicine research enterprise. As the domain of family medicine research is explored, not a few, but billions of people will benefit.

Keywords: Primary health care, family practice, family medicine, research domain, research agenda

INTRODUCTION

Like miners harvesting ore at the rock face, family physicians dwell and work where medicine meets people living out their lives in the particulars of their own circumstances. Family physicians, sometimes called generalists or general practitioners, accept whatever any of the individuals in their communities choose to put forward for consideration by their personal doctor and attempt to make sense of it. For most people, most of the time, the problem is managed effectively right there in the family physician’s office, but many problems require additional interventions, possibly involving a host of medical specialists, other health professionals, and community resources. It is the task of the family physician to work with patients to integrate whatever care and services are necessary and possible so that an individual patient’s concern can be addressed optimally. This integration is a complex, intellectual task, not merely administrative coordination. Integration involves recognition of perhaps hidden relationships and pulling together all the sometimes disparate parts into a coherent whole that has meaning, not just for other doctors or health care systems, but for a particular person who needs some help becoming whole.

Such a realm of endeavor is vast in its scope, full of opportunities for the curious mind to learn about the origin and nature of health, disease, and illness and how people get sick and how they get well. It resists a sharp demarcation that announces with resounding clarity what is in and what is out of the domain. While the domain of family physicians is informed by labeling and counting the problems patients bring, it is not adequately captured by merely summing diagnoses seen at various frequencies. Indeed, since by definition all medical and health problems exist in family medicine, the common approach of defining a research domain by the problem it aims to address is not especially helpful in an effort to exclude items from the domain of family physicians. Further, since no particular technology or single research method clearly demarcates the domain, it eludes containment from these perspectives. In short, the case for absolute exclusion of any of the phenomena of medicine and health care from family medicine may not be sustainable in every instance, leaving the borders vague, disputable, and possibly frustrating to those wanting a clear boundary or a definite research agenda.

Nonetheless, it is illogical to claim that something does not exist just because one cannot find its boundaries (such as the universe). Despite the absence of tight jurisdictional boundaries, family medicine is widely recognized to be a coherent and important enterprise, amenable to discovery, development, and implementation. As nations struggle to organize effective, sustainable health care systems for all their people, a foundation of primary care (first, foremost, fundamental care) is known to be essential,1–3 and family physicians have been unequivocally identified as providers of this foundation of care.4 Learning how best to provide health care depends to a large extent on the willingness of family physicians to discover, understand, invent, and innovate. Others can exhort, but family physicians must seize the opportunities available to them, sometimes only to them, in their daily partnerships with their patients if people are to benefit fully from the collective investments made in their country’s health care enterprise.

While there are heralded saints of research among family physicians,5–8 the research enterprise has yet to be institutionalized worldwide into the core of family medicine. The purpose of this article is to contribute to deliberations about how to correct this disciplinary deficiency by drawing on decades of thoughtful consideration by others to characterize the research domain of family physicians. The intent is not to pronounce a tidy, correct answer, nor to exhaust the possibilities. Rather, the intent is to present 6 perspectives to reveal that without doubt there is a domain of family medicine research that is important and ripe for development.

THE ECOLOGY OF MEDICAL CARE

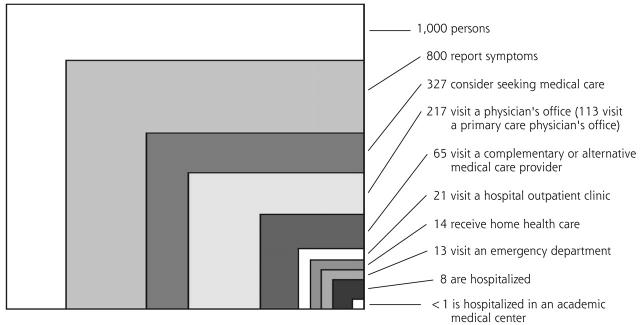

For nearly half a century this model has been used to show the importance of balance in education and research in order to respond to all the medical and health needs of people.9 Updated, it shows a stubborn persistence of the physician’s office as the major platform on which health care occurs for most people in a typical month.10 When organized into the boxes as shown in Figure 1▶, one notion of the domain of family medicine research leaps forth—the investigation of what goes on between approximately one quarter of the population every month and their physicians, specifically in their consultations with their family physicians. This box in the ecology model, as well as its interfaces with public health, self-care, and care in all the other settings, is a domain that is much more than mere constellations of service. It conceptually represents the most prevalent entry point for free-living people into the world of medicine, likely to be rich with the earliest manifestations of disease and equally rich with possible preventive and ameliorating solutions based in knowledge spanning genetics to anthropology to complexity science.

Figure 1.

The ecology of medical care revisited.

Note: All numbers refer to discrete individual persons and whether or not they received care in each setting in a typical month.

From: Green LA, Fryer GE Jr, Yawn BP, Lanier D, Dovey SM. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:2021–2025.10 Reprinted with permission from the Massachusetts Medical Society. Copyright© 2001 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

THE REALM OF CAUSATION

Kerr White has repeatedly challenged family physicians to ask and answer important questions about the origin and relief of disease. He argues that genes and germs are important but rarely sufficient to cause disease, requiring a broadening of our notions of causation. He illustrates part of the domain of family medicine research by pointing out that family physicians are well-positioned to discover answers to 5 types of questions related to what causes people to get and stay sick: circumstances present at the onset of problems, concomitant factors, predisposing factors, factors that precipitate a person to seek health care, and the nature of the therapeutic environment.11 These poorly understood, but discoverable, areas of inquiry about the causes of disease and illness are important to family physicians and their patients and the rest of medicine. They are not trivial, and because much of the phenomena of interest exist in family medicine, but not elsewhere, this domain probably must be researched in family medicine.

KNOWING MEDICINE IN DIFFERENT WAYS

Because research develops knowledge, the ways family physicians know or can know offer other frameworks in which to contemplate family medicine’s domain of research. This complex terrain has been scouted for centuries and mapped by some. Perspectives vary, as illustrated by the following examples.

Tolmin12 examined the claim that during the last 100 years the practice of medicine has been transformed into biomedical science, a transformation that tends to know people, not so much by name, but as body-machines in need of repair by appropriate technicians. He identified as a critical challenge the inclination of contemporary physicians “to know and treat their clients as cases rather than persons, objects of theoretical knowledge rather than subjects for clinical understanding.” He speculated about just how far the fusion of medicine with biological science can afford to go, drawing from epistemological distinctions dating from ancient Greece concerning the relationship of theoretical and practical knowledge and scientific and historical knowledge.

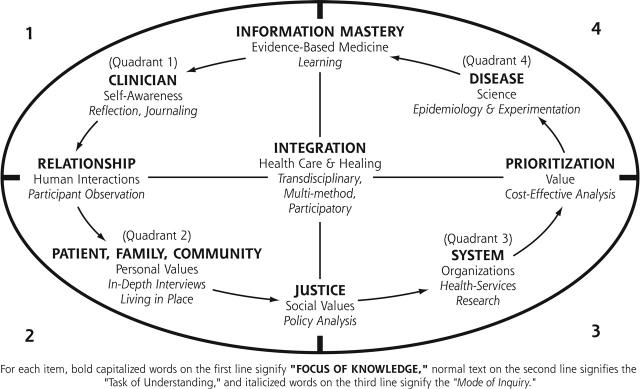

Similarly, the work of Ken Wilber13 organizes what can be known into 4 quadrants: the inner and outer realities of individuals and groups of individuals. This approach has been elaborated by family physicians to identify why and how family physicians can and do seek knowledge, as shown in Table 1▶.14 The domain of family medicine research can include or emphasize each of these ways of knowing, and perhaps most importantly, how these different ways of knowing can be integrated into a coherent whole that has meaning for the patient. It is important to focus intentionally on understanding and meaning, not just mechanical repairs through pharmaceuticals and procedures. Herein lies important opportunities for participatory research in which patients are partners.15 Because many family physicians are open to all these ways of learning and knowing, they represent an important resource to all of medicine, because they can use a spectrum of qualitative and quantitative methods and follow people over time to enlarge what is known about health, disease, and treatment as experienced by individuals and groups of individuals.

Table 1.

Ways of Knowing and Seeking Medical Knowledge

| Inner Reality | Outer Reality | |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | Quadrant 1 | Quadrant 4 |

| Type of knowledge | “I” knowledge | “It” knowledge |

| Why | Understanding the clinician is essential to family practice, since in part “the doctor is the drug” | Understanding that natural phenomena and interventions to affect them comprise the biological basis of medical practices |

| What | Knowledge of the clinician | Disease-specific knowledge of clinical phenomena |

| How | Self-reflection, journaling | Observation, epidemiology, experimentation |

| Who | Reflective clinicians | Detached observers |

| Where | Practice | People or parts of people |

| Collective | Quadrant 2 | Quadrant 3 |

| Type of knowledge | “We” knowledge | “It” knowledge |

| Why | The voices of patients, families, and communities are central to the goals and effectiveness of family practice | Family practice operates within a systems context, which must be understood to enhance its effectiveness |

| What | Knowledge of the patient in context | Systems knowledge |

| How | Participatory research | Health services research |

| Who | Participant observers | Health services researchers |

| Where | Community or practice | Health care system |

THE NATURE OF THE WORK OF FAMILY PHYSICIANS

The practice setting provides an organizing framework for conceptualizing the research domain of family medicine. Rudebeck,16 reflecting on real-life situations in practice, noted that the field of potentially relevant knowledge and skills (for family physicians) is infinite, yet it requires specification to be accomplished. His perspective and review of influential texts and articles evolved a list of specifications of family medicine that characterize the work of family physicians. He summarized these as follows: serving as the point of first contact (with implications of treating symptoms without disease, probabilistic problem-solving, early diagnosis, accepting uncertainty inherent in complexity), committing to a person as well as a disease, adopting a family orientation, incorporating the context in which the patient lives, preventing disease and promoting health, encouraging autonomy of patients, and accepting any type of problem. This stipulation of the work of family medicine provides a functional and task-oriented categorization of the domain of family medicine, each component of which is amenable to enhancements through research.

Taking a medium-term view, Ian McWhinney formulated the unfinished business of family medicine research into 3 areas embedded in the work of family physicians: appropriate technology for primary care, making the implicit explicit, and the articulation of theory.17 He used the term technology to mean more than tools used with hands, such as rapid diagnostic tests, clinical procedures, and monitoring devices, to include the way practice is organized to accomplish specific objectives, eg, prevention, home care, and integration of care. Part of what needs to be made explicit is how family physicians diagnose and manage conditions, how family physicians learn in practice, and how family physicians refute erroneous advice. He suggested that the theory on which family medicine is based is about the connections among human experience, life events, and relationships, and how they interact with health and illness. This formulation of unfinished research business for family medicine exposes immediate, tantalizing opportunities in the domain of family medicine research. Seizing them requires a mix of scientific methods intellectually suitable for a domain in which (1) what things mean to humans matters, (2) the limited relevance of generalization in family medicine is appreciated, (3) the importance of the context in which events occur is recognized, (4) the limitations of causal thinking are accepted, and (5) the impracticality of expecting to accomplish perfect prediction in human affairs is not considered a failure.17

A further means of focusing research on the work of family physicians is by classifying and counting the reasons people come for consultation, the diagnoses made, the assessments and treatments pursued, and measures of results. Lists have been developed that permit quantification of what occurs most often in family medicine, and there is widespread agreement that mastery of the common conditions is a critical part of being a family physician.18–20 When symptoms and problems are followed over time and organized into episodes, a much richer tapestry emerges that permits investigation of the natural history of conditions and the transitions of symptoms and problems as time goes on.21–23 It is difficult to imagine how this type of naturalistic inquiry24 can be accomplished absent vigorous exploration in family practice.

These 3 ways of looking at the work of family physicians signal a large domain of research that effects not a few, but millions of people on a daily basis. There is probably no one better positioned than the family physician to investigate for people of all ages and walks of life the nature and results of what happens in daily, frontline medical practice.

CATEGORIES RESEARCHERS LIKE TO USE

Health services researchers often divide health care into primary, secondary, and tertiary care, and each of these levels of care can be studied (although people with their problems and diseases have a nasty habit of not respecting these levels of care). Family physicians may work at each of these levels. Research can be about any or all 3 of the levels and further classified at each level as follows: basic research about mechanisms, methods, and theory; clinical research (recently defined as “a component of medical and health research intended to produce knowledge valuable for understanding human disease, preventing and treating illness, and promoting health.”)25; health care (services) research, including studying the structure, function, and outcomes of health care26; and health systems (policy) research. Another important category of research is educational research, and when it concerns the education and training of family physicians, it would readily qualify for membership in the domain of family medicine. The inclusion of clinical research, health care research, and educational research in the domain of family medicine has been obvious, but basic research and policy research probably have not been so frequently identified with family physicians.

Perhaps the relative inattention to policy and to measuring the effects of family medicine in a coherent, theoretical framework partially explains why it remains necessary in many countries to reexplain what family medicine is and what family physicians do that matters.27–30 A heavy emphasis in the domain of family medicine research on the level of primary care may partially explain the often unrealized integration of care across the full spectrum of services involving several levels of care. There is no readily apparent reason why the research domain of family physicians should be restricted to only one level of care. To the extent that family physicians integrate care for individuals, imagine causal webs and innovations, and teach next generations of clinicians, their research domain will of necessity cut across these levels of care.

THE WHEEL OF KNOWLEDGE

Some conceive of the research domain of family medicine as being a locus of the scholarship of application, or engineering into practice what others discover. This line of thought is indeed linear, typically beginning with an idea or opportunity in another field which matures in a way that leads someone to think family physicians should do something in their practices because of what was discovered. In this view, family physicians are seen as recipients of knowledge, and their investigative domain focuses on translating research into their practices through applications that can work for their patients, possibly measuring subsequent impact. For example, health behavior counseling concerning physical inactivity that is demonstrated to work in a research setting quite different from daily practice could be modified to fit into daily routines achievable in the family physician’s office, and whether or not it worked there could be assessed. This type of inquiry can be very important and have a large impact on patients.

This conceptualization can be expanded into a wheel of knowledge14 (Figure 2▶) that creates within family medicine iterative loops of discovery. In this way of thinking, rather than serving as a relatively passive recipient of breakthroughs in knowledge from elsewhere, reflective family physicians are initiators of research by constantly identifying challenges and opportunities within their practices. They then seek remedies that are evidence based, just, and placed into context amidst other priorities. Assessing what happens may lead to a revision of ideas and a never-ending quest of improvement. In this framework, the research domain is seen to be derived from practice experience, be about practice, and be used in practice in a recurring cycle. Some would identify in the wheel elements they would label as quality improvement and practice audit, instead of research. Nonetheless, this process reflects a scientific enterprise that can be incorporated into the domain of family medicine research.

Figure 2.

Generalist wheel of knowledge, understanding, and inquiry.

FURTHER COMMENTS

These perspectives, broad as they are, do not exhaust the description of the domain of family medicine research, and yet these perspectives alone present a potentially immobilizing panoply of opportunity and duty. Lacking the relative simplicity and singular focus of a domain bounded by one organ or disease, family physicians are challenged to enter their research domain without getting lost. While the natural predisposition of most family physicians is that of the generalist, research requires adopting a selected focus and persistent attention to a particular question using explicit methods. The most compelling foci of investigation will vary among investigators in different countries, with their various challenges and resources, and are best identified locally.31 The tension between the broad perspective required in the full domain of family medicine and the specificity and granularity necessary in research is not an insurmountable challenge, as made obvious by the research contributions made now and throughout history by family physicians.

Successful exploration of vast domains, such as the research domain of family medicine, requires curiosity, courage, focus, training, collaboration, patience, resilience, and dedication—not unlike the requirements of being someone’s family physician. Just as family physicians focus on one patient at a time, even when dwelling in the midst of intractable health deficiencies afflicting an entire community, successful family medicine researchers take on questions one or two at a time, eating the proverbial elephant, “one bite at a time.”

All aspects of the domain of family medicine research will not be equally compelling at all times, and the versatility of family medicine researchers guarantees their relevance to the investigative enterprise of greatest interest in their locations. What at a conceptual level can seem too huge to begin can become immediately accessible and achievable when fertile areas for engagement are defined. For example, in the United States there are urgent needs for family medicine research focused on resolving disparities of health and health care associated with race, reliable delivery of health behavior counseling concerning the true causes of premature mortality (physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, tobacco use, risky drinking, unsafe sex), exploration of mind-body connections, integration of care for people with common chronic diseases (eg, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, depression), achieving continuity in the information age with asynchronous communication, and careful description of the natural history of symptoms and clinical conditions linked to new genetic knowledge. These areas of investigation are immediately available for discovery in the United States, but family physicians in other countries are likely to identify other areas of greater importance to them and their patients.

CONCLUSION

The domain of family medicine research is large. It is knowable, at any given time, as the research done by reflective and curious family physicians. However conceived, within the domain of family medicine research are gaps in knowledge and understanding that are destined to remain gaps until family physicians and their colleagues examine them using relevant, scientific methods. Thus, the potential research domain is rich with opportunity, invites the best minds, is ready for exploration, and is poised to benefit not a few, but billions of people. Indeed, it seems unlikely that medical research can ever be complete without a robust family medicine research enterprise.

Conflicts of interest: none reported

REFERENCES

- 1.Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1992.

- 2.Starfield B. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998.

- 3.Starfield B. Is US health really the best in the world? JAMA. 2000; 284:483–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine. Donaldson JS, Yordy KD, Lohr KN, Vanselow NA ed. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [PubMed]

- 5.Mair A. Sir James Mackenzie MD. 1853–1925. General Practitioner. Edinburgh and London: Churchill Livingstone; 1973.

- 6.Pemberton J. Will Picles of Wensleydale. London: Geoffrey Bles; 1970.

- 7.Hames CG. Evans County Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Epidemiologic Study. Introduction. Arch Intern Med. 1971;128:883–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huygen FA. Family Medicine: The Medical Life History of Families. Nijmegan, The Netherlands: Decker en van de vegt; 1978.

- 9.White KL, Williams TF, Greenberg B. The ecology of medical care. N Engl J Med. 1961;265:885–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green LA, Fryer GE, Yawn BP, Lanier D, Dovey SM. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J of Med. 2001;344:2021–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White KL. Fundamental research at the primary care level. Lancet. 2000;355:1904–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tolman S. In: Delkeskamp-Hayes C, Gardell Cutter MA, eds. Science, Technology, and the Art of Medicine. The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1993:231–24.

- 13.Wilbur K. A Brief History of Everything. Boston, Mass: Shambhala Publications, Inc; 1996.

- 14.Stange KC, Miller WL, McWhinney I. Developing the knowledge base of family practice. Fam Med. 2001;33:286–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macaulay AC, Commanda LE, Freeman WL, et al. Participatory research maximises community and lay involvement. North American Primary Care Research Group. BMJ. 1999;319:774–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudebeck CE. General practice and the dialogue of clinical practice. On symptoms, symptom presentations, and bodily empathy. Scand J of Pri Health Care. 1992;Suppl 1:1–87.

- 17.McWhinney IR. Primary care research in the next twenty years. In: Norton PG, Stewart M, Tudiver F, Bass MJ, Dunn EV, eds. Primary Care Research. Traditional and Innovative Approaches. Newbury Park, London, and New Delhi: Sage Publications; 1991:1–12.

- 18.Fry J. Common Diseases. Their Nature, Incidence and Care. Lancaster, England: MTP Press Limited; 1979.

- 19.Green LA, Phillips RL, Fryer GE. The nature of primary medical care. In: Jones R, Britten N, Culpepper L, et al, eds. The Oxford Textbook of Primary Care. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003.

- 20.Saultz J. Comprehensive care. In: Textbook of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2000:79–10.

- 21.Lamberts H, Wood M. International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1987.

- 22.Lambert H, Brouwer JH, Mohrs J. Reason For Encounter and Episode and Process-Oriented Standard Output From the Transition Project. Amsterdam. Department of General Practice, University of Amsterdam; 1991.

- 23.Hofmans-Okkes IM, Lamberts H. The international classification of primary care (ICPC): new applications in research and computer-based patient records in family practice. Fam Pract. 1996;13:294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McWhinney IR. The naturalist tradition in general practice. J Fam Pract. 1977;5:375–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinig SJ, Quon AS, Meyer RE, Korn D. The changing landscape of clinical research. Acad Med. 1999;74:725–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Maeseneer JM, De Sutter. Why research in family medicine? A superfluous question. Ann Fam Med. 2004:2(Suppl):S17–S22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mold JW and Green LA. Primary care research. Revisiting its definition and rationale. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:206–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olesen F, Dickinson J, Hjortdahl P. Generalist practice—time for a new definition. BMJ. 2000;320:354–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Health I, Evans P, vanWeel C. The specialist of the discipline of general practice. Semantics and politics mustn’t impede the progress of general practice. BMJ. 2000;320:326–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WONCA Europe 2002. The European Definition of General Practice/Family Medicine. Evans P, ed. Available at: http://www.medisin.ntnu.no/wonca. Accessed January 15, 2003.

- 31.Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Ebell MH, et al. Analysis of questions asked by family doctors regarding patient care. BMJ. 1999;319:358–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]