Abstract

A time-dependent theory for the evolution of water on Mars is presented. Using this theory and invoking a large number of observational constraints, I argue that these constraints require that a large reservoir of water exists in the Martian crust at depths shallow enough to interact strongly with the atmosphere. The constraints include the abundance of atmospheric water vapor, escape fluxes of hydrogen and deuterium, D/H ratios in the atmosphere and in hydrous minerals found in one Martian meteorite, alteration of minerals in other meteorites, and fluvial features on the Martian surface. These results are consonant with visual evidence for recent groundwater seepage obtained by the Mars Global Surveyor satellite.

Given the low temperature and pressure at the surface of Mars, the existence of liquid water at shallow depths was considered once to be impossible at the present epoch. Nevertheless, the Mars Orbiter camera on the Mars Global Surveyor spacecraft apparently has produced the first visual evidence of recent transport of a fluid, presumably water, from the interior to the surface of Mars (1). These observations actually are the culmination of a series of discoveries strongly suggesting the presence in the Martian crust of liquid water that interacts efficiently with the atmosphere. This evidence involves the presence of modified minerals in Martian meteorite samples that require the intervention of liquid water (2–4) and, in particular, measurements of the D/H ratios in hydrous minerals created hundreds of millions of years ago (5) that can be virtually identical with the atmospheric D/H ratio at the present time (6).† It has been argued that this surprising result requires efficient exchange of water between the atmosphere and an underground reservoir containing much more water than the atmosphere, such that the amount of hydrogen and deuterium lost by escape from space over the past several hundred millions of years is small compared with that in the underground (or polar-cap) reservoirs (7, 8). On the other hand, to account for the amount of isotopic fractionation in atmospheric water vapor, very large escape fluxes at very early times and a water supply hundreds of meters deep, sufficient to create fluvial features, were required. In this paper, a time-dependent treatment of hydrogen and deuterium evolution, developed for a study of the evolution of water on Venus (9), will be applied to the Martian problem. A model that explains the evolution of Martian water adequately must be able to account for the near equality of D/H ratio in contemporaneous water vapor and water of hydration in minerals formed many hundreds of million years ago, the presence of crustal liquid water capable of modifying other crystals in Martian meteorite samples, today's atmospheric D/H ratio, and the presence of enough water at early times to account for surface fluvial features. It is desirable also that the model be insensitive to the relative efficiency of D and H escape and the D/H ratio in primitive Martian water. I shall argue that satisfying these constraints excludes a large number of mechanisms that might account for the present D/H ratio in favor of one involving efficient exchange of water between atmosphere and crust now and in times past.

Evolution of Hydrogen on a Planet.

General considerations.

The evolution of hydrogen and deuterium on a planet under certain circumstances can be described by the relationships

|

1 |

|

2 |

where H and D are the total column abundances of hydrogen and deuterium in all forms, such as H2O, HDO, H2, HD, H, and D; φ is the hydrogen escape flux; f, the fractionation factor, is the relative efficiency of D and H escape; and P1 is the strength of endogenic and exogenic sources of H with D/H ratio Rs. Ro is the initial D/H ratio in the reservoir. It is necessary to assume that f is constant and that the escape flux φ is proportional to H at a constant ratio k,

|

3 |

for the relationships in Eqs. 1 and 2 to hold (9). k can be evaluated if the flux φ1 and the size of the reservoir H1 are known at any given time, i.e., today. Under these circumstances, the time for an enhancement ρ in the D/H ratio R relative to Ro to be attained (9, 10) is given by

|

4 |

which means

|

5 |

Comet fluences on the terrestrial planets seem to be small enough (9, 11–13) that P1/φ1 can be taken to vanish as far as exogenic sources are concerned. Eventually, I shall consider cases in which endogenic sources on Mars might be appreciable. If P1/φ1 vanish

|

6 |

|

7 |

Thus, the size of the present hydrogen or water reservoir, H1, can be determined if ρ, f, and t1 are known. Conversely, t1 can be determined if the size of today's reservoir H1 and the fractionation factor f are specified. With k constant, Ho can then be calculated from Eq. 1 as a function of f.

Earth.

In the case of Earth, the escape flux, 2.7 × 108 cm−2⋅s−1 (14), is so small compared with the size of the reservoir, which is the ocean, that

|

8 |

In 4,500 million years (Myr), the enhancement in D/H is given by

|

9 |

and ρ lies between 1.0015 and 1.002, no matter what the relative efficiency of D and H escape f may be.

Venus.

I have recently discussed the case of Venus (9). ρ is very large—about 150 if Ro is the same as in terrestrial water. Uncertainty in the H and D escape fluxes is still so great, however, that this high level of fractionation may require an early hydrogen reservoir Ho amounting to 150 to 225 m of water at a time t1 of about 4 billion years (Gyr). On the other hand, it might mean that today's water appeared on the surface only about 500 Myr ago and that Ho was only about 5 m. Thus, the water present today with its very high fractionation ratio might be the remnant of the global-resurfacing event several hundred million years ago.

Mars.

The case of Mars is considerably more complicated than that of the other two terrestrial planets on which water is present. Instruments on the Mariner and Viking spacecraft measured the density and temperature of hydrogen gas at the Martian exobase (15, 16) and the amount of water vapor above the surface in the atmosphere (17).‡ These measurements revealed that hydrogen was escaping from Mars by the Jeans mechanism at the rapid (globally and solar-cycle averaged) rate of 2.4 × 108 cm−2⋅s−1 (18), whereas the average atmospheric burden of water vapor was a meager 10 per μm. Actually, the Jeans loss rate, although large, provides only a lower limit to the total escape flux, because other, nonthermal modes of escape may also be important, as they are on Earth and Venus, where they dominate. Still, at the Jeans rate alone, water escapes from Mars at an annual rate of about 155,000 tonne. [Oxygen accompanies the escaping hydrogen in a nonthermal process at the rate of about one atom lost for every two hydrogen atoms (19, 20).] The lifetime of the atmospheric water vapor, with a global burden of 1.4 × 109 tonne, is thus only 8,800 yr. Furthermore, the D/H ratio in atmospheric water vapor is (8.1 ± 0.3) × 10−4 or (5.2 ± 0.2) × SMOW, the ratio in standard mean ocean terrestrial water (6).† This modest fractionation state would have been attained in a very short time by Rayleigh fractionation if this atmospheric sample has been isolated from its source and originally had a D/H ratio 1 or 2 times that of SMOW. If H1 is only 10−5 m, and φ1 is 2.4 × 108 cm−2⋅s−1, then

|

10 |

The value of f for Mars is controversial. Yung et al. (21) calculated a fractionation factor of 0.32 for Jeans escape; Krasnopolsky et al. (22) have concluded, from measurements of D Lyman-α, that it is only 0.02. It also seems from studies of the D/H ratio for water of hydration in Martian meteoritic hydrous minerals that Ro may be approximately twice as large as the D/H ratio in standard mean ocean terrestrial water (23). Hence, ρ may be as small as 2.6. In this paper I shall let f be a parameter with values in the range 0.02 to 0.4 and consider two values for ρ, 5.2 and 2.6. From Eq. 5 it follows that t1 is only between 15,000 and 24,000 yr if ρ is 5.2, or between 8.3 and 14,000 yr if ρ is 2.6. The initial amount of water, from Eq. 1, would have been 54–150 μm in the first case and 25–50 μm in the second. Thus, if the water vapor in the atmosphere today was produced by a singular event that released water, normally immobilized as ice, into the atmosphere, that event must have occurred very recently and involved the release of only 10-100 μm of water vapor. This result is a consequence of the large magnitude of the escape flux compared with the atmospheric hydrogen burden and the modest amount of fractionation that has occurred.

If, on the other hand, the atmospheric water vapor is communicating with a large reservoir somewhere on the planet continuously or at a sufficiently high frequency that the D/H ratio in the atmosphere and that in the reservoir are effectively the same at any given time, the situation becomes very different. In view of the short lifetime of today's atmospheric water vapor, it follows that this exchange between atmospheres and reservoirs needs to occur at an effective period that is short, perhaps as low as 104 yr. If there should be a subsurface liquid supply that vents regularly enough to the atmosphere, this condition could readily be satisfied. In this case, the relationship in Eq. 5 in the form

|

11 |

gives the size of the present reservoir in meters. If fractionation has been going on with a constant decay constant k for, say 4 Gyr, then

|

12 |

is somewhere between 1.6 and 2.7 m for ρ = 5.2 and between 2.8 and 4.6 m if ρ = 2.6 (Fig. 1). Eq. 1 then requires Ho, 4 Gyr ago, to have been between 2.6 and 15 m on the one hand, or 14 and 12.3 m on the other (Fig. l). Notice that, with a given escape flux and fractionation factor, the more modest fractionation requires a larger reservoir H1 at present but a smaller one originally. The ratio Ho/H1 is small enough and k is large enough that the same value of Ho is obtained from the classic Rayleigh fractionation relationship

|

13 |

as from Eq. 1.

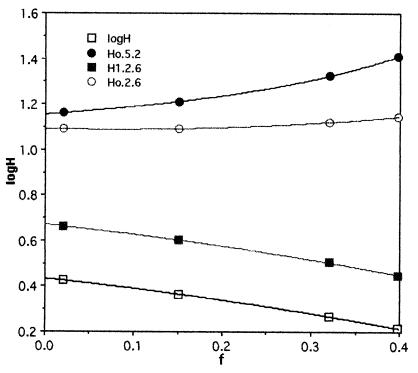

Figure 1.

The log of the globally averaged depth of water stored in the Martian crust today (H1) and at early times Ho for two values of ρ, the ratio of D/H in today's atmospheric water vapor to the primordial ratio (2.6 and 5.2). These results are for a simple unconstrained escape of hydrogen with a constant ratio of escape flux to H, the depth of the hydrogen supply.

Hydrous Minerals of the Shergotty, Nakhla, and Chassigny (SNC) Meteorite Class.

There is compelling evidence, indeed, that the water of the crust is in the liquid phase (2–5). Alterations of minerals in the crust manifested in Martian meteorite samples can be caused only by liquid water. Furthermore, it seems that this crustal water is exchanging efficiently with the atmosphere. Evidence for such an exchange has been provided by the study of the D/H ratio in hydrous minerals, particularly apatite, in the Martian meteorite Zagami (5). The D/H ratio in the water of hydration is not more than 4% below the present atmospheric ratio and may be taken to be arbitrarily close to that ratio, even though the intrusion and crystallization that produced the minerals occurred between 0.18 and 1.3 Gyr ago (5, 7, 8). In calculating the volume of the liquid reservoir, it was assumed that the escape flux was constant and at today's level for the entire period since crystallization. The present treatment permits the escape flux to follow the amount of water present at a constant ratio k. The liquid crustal reservoir implied by any assumed fractionation ρ, 1.04 or smaller, during the time tz since crystallization, follows again from the relationship in Eq. 11, with t1 replaced by tz = 1,300 or 180 Myr. Thus,

|

14 |

for tz = 180 Myr, and

|

15 |

for tz = 1.3 Gyr.

Hz can be calculated from Eq. 1 and Ho from Eq. 13. The results as a function of f are shown in Figs. 2 and 3 for tz = 1.3 and 0.18 Gyr, two values for ρ(tz) of 1.01 and 1.04 and two values for the overall fractionation of 2.6 and 5.2. If tz is as long as 1.3 Gyr, very large contemporary reservoirs in the range of 50–250 m are required, as are primordial depths between 200 and 2,000 m. If ρ(tz) is as small as 1.01 and f is 0.3 or larger, similarly large amounts of water are implied, even if tz is only 180 Myr (Fig. 3). Thus, early underground reservoirs able to supply the water needed to produce valley networks and catastrophic flood channels (24, 25) not only are consistent with the consequences of the Zagami and atmospheric measurements but are required by them.

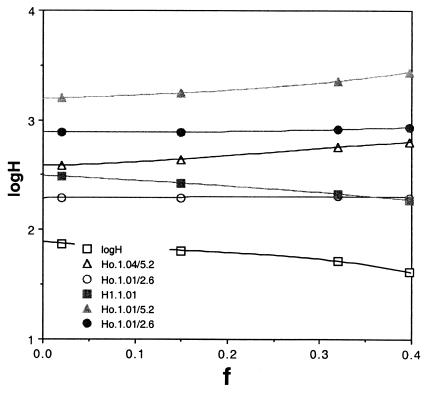

Figure 2.

The log of the globally averaged depth of water stored in the crust today (H1) and at early times Ho for two values of the total D/H fractionation ρ = 2.6 and 5.2 and for two possible values of the fractionation occurring during tz, the time when Zagami apatites were crystallized, 1.04 and 1.01. Here, tz is 1.3.

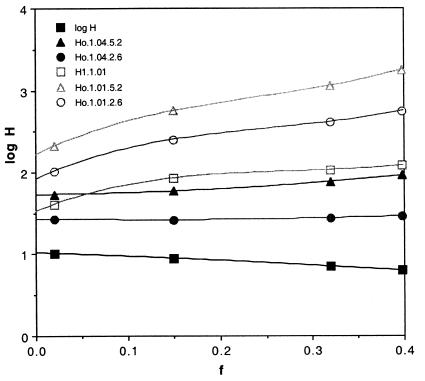

Figure 3.

The log of the globally averaged depth of water stored in the crust today (H1) and at times Ho for two values of the total D/H fractionation, ρ = 2.6 and 5.2, and for two possible values of the fractionation occurring during tz, the time when Zagami apatites were crystallized, 1.04 and 1.01. Here, tz is 180 Myr.

Polar Caps.

Obviously, the role of water stored in the polar caps needs to be considered. These polar caps (24) are large enough to cover the planet with 30 m of water if it should be mobilized. Clearly, they could be in play in episodic releases of water of the sort we have already discussed in Venus. The 30-m estimate is very large compared with the values of H1 obtained in the simple model represented in Fig. 1. Thus, if the polar caps are part of the reservoir presently exchanging with the atmosphere, k would be very large:

|

16 |

and

|

17 |

Tens of billions of years would be needed to fractionate Martian water at a constant k and leave 30 m of it today with ρ between 2.6 and 5.2. On the other hand, as we have seen in the Hydrous Minerals section and Figs. 2 and 3, the present-day reservoirs needed to explain the Zagami measurements can be equal to or greater than 30 m. Thus, the polar caps could be involved in the system if they can be mobilized with a frequency considerably greater than tz−1.

The discussion of the consequences of the level of fractionation in the Zagami water of hydration assumes that the crustal water involved was liquid before the intrusion. If that was not so, and the water was ice melted during the intrusion event, consequences would be otherwise. Because the D/H ratio in ice is 1.27 times larger than it is in the water vapor with which it is in equilibrium (21), the D/H ratio of atmospheric water vapor tz years ago would have been smaller than today's ratio by this factor of 1.27. The amount of water vapor present today and exchanging with the atmosphere at that time would need to have been at most approximately 20 m in depth (Table 1). The amount of water implied at early times Ho would amount to at most 55 m. This quantity would have been altogether inadequate to create the fluvial surface features on the Martian landscape.

Table 1.

Amount of water in meters required to produce ρ = 1.27 in a time tz

| f |

tz = 1.3

Gyr

|

tz = 180 Myr

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Hz |

Ho

|

H1 | Hz |

Ho

|

|||

| R1/Ro = 5.2 | R1/Ro = 2.6 | R1/Ro = 5.2 | R1/Ro = 2.6 | |||||

| 0.01 | 12.2 | 13.8 | 55.0 | 18.1 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 7.1 | 2.3 |

| 0.32 | 8.5 | 10.1 | 40.8 | 13.2 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 4.9 | 1.6 |

Thus, we must conclude that the crustal water of hydration for the Zagami meteorite apatites was in the liquid, not the solid, phase before intrusion occurred.

Steady State.

Suppose that water is being supplied to the atmosphere by mobilization of ice in the polar caps and crust or by some kind of volcanism or hydrothermal activity at about the same rate it is being lost to space (P1 = φ1), and that the D/H ratio in these sources Rs is the same as the primitive ratio Ro. Then Eq. 4 requires that the time t1 required to produce an amount fractionation ρ is given by

|

18 |

This interval is only about 4,000 yr. The largest value of ρ permitted is f−1. This enhancement is 50 for f = 0.02 and 3.12 for f = 0.32. Thus, ρ = 5.2 requires that f be less than 0.19 if such a steady state should exist. On the other hand, the atmospheric water vapor might be in a mature, steady state, where production of both D and H from crustal and polar-cap reservoirs is balanced by escape. In that case, ρ will be either 50 in the case of f = 0.02 or 3.12 in the case of f = 0.32. The former case would call for a D/H ratio of 1.7 × 10−5 in the water emerging from the reservoirs. The latter would require that it be 2.6 × 10−4. The first alternative is not supportable; the second is reasonable (23). However, it is not consonant with the evidence from Zagami that the water in the reservoir now and at tz have a D/H ratio of about 8.1 × 10−4. Thus, it is not likely that Martian atmospheric water vapor is in a steady state.

The analysis presented here is based on the assumption that the escape flux is dominated by the Jeans mechanism. The escape flux used and, hence, the decay constant k, are those calculated for Jeans escape. k is assumed to be constant so that φ increases linearly with H. If this condition should have prevailed at all times back to 4.5 Gyr ago, Ho would have been no greater than some tens of meters, except in the case of tz = 1.3 Gyr (Fig. 2). The values of Ho in Figs. 2 and 3 are calculated on the basis of the Rayleigh fractionation formula shown in Eq. 13. To obtain this large value of Ho/H1, the time available before the minerals in Zagami crystallized a decay constant k of about 2 × 10−5 would be required. This result would hold, if, for example, ρ at tz is 1.04 times ρ at t1 and tz = 1.3 Gyr. In 3 Gyr, according to Eq. 1, an amplification of only about 10% would have occurred. It was for this reason that it has been necessary to evoke very large escape fluxes from early Mars, driven by enhanced solar extreme UV (7, 8, 26). To achieve the hundreds of meters of water required for Martian fluvial features (24), the escape flux must have been on average about two orders of magnitude larger than it is today during the first billion years. Limits to solar radiance and limits on hydrogen diffusion would place constraints on the early escape flux (7, 8).

Conclusions

The properties of atmospheric water vapor and the hydrogen isotopic ratio in it and in SNC crystals, together with other evidence for modification of minerals in those meteorites by liquid crustal water, require an efficient exchange of water between the planetary interior and the surface. The temporal evolution of the D/H ratio in Martian water implied by the Zagami apatite studies and by the presence of early outflow channels and valley networks can be accounted for by such an exchange, which has now been strongly suggested by the Mars Global Surveyor images of widespread contemporaneous or recent seepage of groundwater. An alternative explanation for the modest fractionation of atmospheric deuterium requiring a recent episode of mobilization of ordinarily frozen water, along with other scenarios requiring that crustal water be in the solid phase, are not credible in the face of the visual and mineralogical evidence.

Acknowledgments

I thank N. M. Donahue, J. M. Kasting, D. M. Hunten, B. Jakosky, and J. C. G. Walker for useful criticisms and suggestions.

Abbreviations

- Myr

million years

- Gyr

billion years

Footnotes

Bjoraker, G. L., Mumma, M. J. & Larson, H. P. (1989) Bull. Am. Astron. Soc. 21, 990 (abstr.).

Barker, E. S. (1974) Bull. Am. Astron. Soc. 6, 371 (abstr.).

References

- 1.Malin M C, Edgett K S. Science. 2000;288:2330–2344. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gooding J L, Wentworth S J, Zolensky M E. Meteoritics. 1991;26:135–143. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trieman A H, Barrett R A, Gooding J L. Meteoritics. 1993;28:86–97. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swindle T D, Grier B A, Bursland M K. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1995;50:1001–1055. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson L L, Hutcheon I D, Epstein S, Stolar E M. Science. 1994;265:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.265.5168.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owen T, Maillard J P, de Berg C, Lutz B L. Science. 1988;240:1767–1770. doi: 10.1126/science.240.4860.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donahue T M. Nature (London) 1995;374:432–434. doi: 10.1038/374432a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donahue T M. In: Volatiles in the Inner Solar System. Farley K A, editor. New York: Amer. Inst. Phys.; 1995. pp. 154–166. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donahue T M. Icarus. 1999;141:226–235. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gurwell M A. Nature (London) 1998;378:22–23. doi: 10.1038/378022b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shoemaker E, Wolfe R. In: The Satellites of Jupiter. Morrison D, editor. Tucson: Univ. of Arizona Press; 1982. pp. 277–339. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shoemaker E, Wolfe R, Shoemaker C. In: Global Catastrophes in Earth History. Sharpton V L, Ward P D, editors. Boulder, CO: Geol. Soc. of Am.; 1990. pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shoemaker E, Weissman P, Shoemaker C. In: Hazards Due to Comets and Asteroids. Gehrels T, editor. Tucson: Univ. of Arizona Press; 1994. pp. 313–335. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu S C, Donahue T M. J Atmos Sci. 1974;31:2238–2239. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson D E, Jr, Hord C W. J Geophys Res. 1971;28:6666–6672. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sief A, Kirk D B. J Geophys Res. 1977;82:4364–4379. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farmer C B, Davies D W, Holland A L, LaPorte D D, Doms P E. J Geophys Res. 1977;82:4225–4248. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krasnopolsky V A. Icarus. 1993;101:33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McElroy M B, Donahue T M. Science. 1972;177:986–988. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4053.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox J L. Geophys Res Lett. 1993;20:1747–1750. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yung Y L, Wen J-S, Pinto J P, Allen M, Pierce K K, Paulson S. Icarus. 1988;76:146–159. doi: 10.1016/0019-1035(88)90147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krasnopolsky V A, Mumma M J, Gladstone R R. Science. 1998;280:1576–1580. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leshin L L. Geophys Res Lett. 2000;27:2017–2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carr M H. Water on Mars. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carr M H. Icarus. 1990;87:210–215. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jakosky B. J Geophys Res. 1990;95:1475–1482. [Google Scholar]