Abstract

PURPOSE Medicine is traditionally considered a healing profession, but it has neither an operational definition of healing nor an explanation of its mechanisms beyond the physiological processes related to curing. The objective of this study was to determine a definition of healing that operationalizes its mechanisms and thereby identifies those repeatable actions that reliably assist physicians to promote holistic healing.

METHODS This study was a qualitative inquiry consisting of in-depth, open-ended, semistructured interviews with Drs. Eric J. Cassell, Carl A. Hammerschlag, Thomas S. Inui, Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, Cicely Saunders, Bernard S. Siegel, and G. Gayle Stephens. Their perceptions regarding the definition and mechanisms of healing were subjected to grounded theory content analysis.

RESULTS Healing was associated with themes of wholeness, narrative, and spirituality. Healing is an intensely personal, subjective experience involving a reconciliation of the meaning an individual ascribes to distressing events with his or her perception of wholeness as a person.

CONCLUSIONS Healing may be operationally defined as the personal experience of the transcendence of suffering. Physicians can enhance their abilities as healers by recognizing, diagnosing, minimizing, and relieving suffering, as well as helping patients transcend suffering.

Keywords: Healing; physician-patient relations; philosophy, medical

INTRODUCTION

Medicine is traditionally considered a healing profession, and modern medicine claims legitimacy to heal through its scientific approach to medicine.1 The marriage of science and medicine has empowered physicians to intervene actively in the course of disease, to effect cures, to prevent illness, and to eradicate disease.2 In the wake of such success, physicians, trained as biomedical scientists, have focused on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease.3 In the process, cure, not care, became the primary purpose of medicine, and the physician’s role became “curer of disease” rather than “healer of the sick.”4,5 Healing in a holistic sense has faded from medical attention and is rarely discussed in the medical literature.

Even so, other disciplines have continued an active contemplation of holistic healing. Anthropological explorations of healing involve an active response to distress and distinguish categories related to healing, such as diagnosis and treatment, medical (scientific and nonreligious) and nonmedical (unscientific and religious), technological and nontechnological, and Western and non-Western.6 Psychological conceptions of healing involve reordering an individual’s sense of position in the universe and define healing as “a process in the service of the evolution of the whole person ality towards ever greater and more complex wholeness.”7,8 These definitions of healing focus on issues of social organization, roles, meaning, and personal growth.

The nursing literature reflects increasing concern with healing and the role of the nurse as healer during the past 25 years.9,10 Healing has been defined as “the process of bringing together aspects of one’s self, body-mind-spirit, at deeper levels of inner knowing, leading toward integration and balance with each aspect having equal importance and value.”11 These conceptions associate healing with complexities of meaning and personal understanding that may be related to curing and reflect the traditional caring role of nurses as patient advocates.

The confusion concerning healing in medicine is evidenced by the lack of consensus about its meaning. Science values operational definitions. Yet, medicine promotes no operational definition of healing, nor does it provide any explanation of its mechanisms, save those describing narrow physiological processes associated with curing disease.12–14 Most medical literature addressing holistic healing and using the word in the title never defines the term.15,16 The MEDLINE electronic database reveals no single MeSH heading for “healing”; instead, it adds qualifiers associated with the spiritual and religious aspects of illness and recovery related to psychology and alternative medicine. It could be surmised that modern medicine considers holistic healing beyond its orthodoxy, leaving the promotion of healing to practitioners of alternative or aboriginal medicine17—the nonscientific, nonmedical practitioners described by anthropologists.

That medicine has no accepted definition of holistic healing is a curiosity. If healing is a core function of medicine, then exploration of its symbolic meaning compels organized research of healing phenomena,18 and an operational definition of healing in a holistic sense is warranted. Such a definition would allow the systematic exploration of healing through identifiable and repeatable operations to determine more precisely its phenomena. The knowledge acquired could help both medical trainees and practicing physicians become more effective healers during their therapeutic encounters with patients.19 This report describes the results of a qualitative study of healing, focusing on its operational definition to clarify its meaning.

METHODS

Data were gathered through semistructured interviews conducted by the author.20 Interviews lasted approximately 90 minutes each and were held in person, with the exception of 1 interview by telephone. The interviews consisted of open-ended questions designed to elicit responses of unspecified substance or perspectives.21 Respondents consented to be quoted and were encouraged to expand answers. The questionnaire was field-tested before implementation and shortened after the first interview to focus the inquiry more precisely. The final interview questionnaire is depicted in Table 1 ▶.

Table 1.

Research Interview Questionnaire

|

The author is a social worker and behavioral scientist in a community-based, university-affiliated family practice residency program. The research was initiated as the author’s doctoral dissertation project.22 Preparation for the interviews involved coaching with an anthropologist proficient in qualitative interviewing. Preparation for data analysis involved a review of relevant literature regarding healing, the patient-physician relationship, and medical training in the Western allopathic tradition. Data analysis continued during the decade after the original interviews were completed, stimulated by increasing reports of physician demoralization and dissatisfaction with medicine.

The study was based on the following assumptions: (1) healing remains a core function of medicine; (2) information concerning healing would benefit medical practitioners; (3) the personal, subjective nature of healing could best be explored through qualitative research; (4) useful information regarding healing in medicine might best be gathered from persons familiar with and experienced in the role of allopathic physician; and (5) information of the highest yield might be gained from physicians who have devoted their careers to addressing the topic of inquiry.

The study cohort represented a purposive sampling23 of 7 allopathic physicians, chosen for their “expertise in areas relevant to the research,”24 based on their publications on topics related to healing or their reputations as medical educators. A less-is-more premise that sample sizes of 8 or fewer facilitate a deeper, more detailed analysis determined sample size.25 Interviews were sought to allow spontaneous exploration of meaningful themes and concepts, which would be otherwise impossible through a literature review of the physicians’ published work. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seattle University, and all respondents agreed to be identified by name in this publication.

Six interviews were recorded and transcribed into verbatim transcripts; 1 interview was reconstructed from notes because of a recording failure. Verbatim transcripts were reviewed to check for accuracy and forwarded to the respondents for validation.26 The edited transcripts were loaded into a computer program for managing qualitative research data27 and coded to generate grounded theory as described by Strauss and Corbin.28 Themes, subthemes interrelating themes, and the central story line connecting themes were determined. Data collection and analysis occurred simultaneously, and data were winnowed to core concepts to facilitate manageability.29,30

RESULTS

The coding of the transcripts revealed 3 themes, each with 3 subthemes depicting the relationship of these themes. Verbatim definitions, themes, subthemes, and the central story line are summarized in Table 2 ▶.

Table 2.

Definitions of Healing and Codes

| Respondent | Definitions | Themes | Subthemes |

| Cassell | “Making whole again” | Wholeness | Transformation |

| Kubler-Ross | “Becoming whole again” | Wholeness | Loss/Isolation |

| Saunders | “Finding wholeness” | Wholeness | Suffering |

| Inui | “Well-being and function” | Narrative | Continuity |

| Siegel | “A state of mind” | Narrative | Personal |

| Hammerschlag | “A harmony between the mind, the body and the spirit” | Spirituality | Reconciliation |

| Stephens | “A spiritual experience” | Spirituality | Transcendence |

Story line: Healing is the personal experience of the transcendence of suffering.

Wholeness

Three definitions emphasized the concept of wholeness but differed in the stress on physician or patient experience or in the suggestion that wholeness is discovered as the illness experience unfolds. So defined, healing involves achieving or acquiring wholeness as a person. “If you become whole again,” Kubler-Ross observed, “you’re healed.”

The concept of wholeness as a definition of healing “lacks only one thing,” Cassell noted. “What anybody means by the word ‘whole’ and what it means to ‘make’ whole … much less the word ‘again,’ which implies that the person was whole prior to the healing … [i]f you mind that, then it’s a terrible definition.” For Cassell, to be whole again “is to be in relationship to yourself, is to be in relationship to your body, to the culture and significant others.” To be whole as a person is to be whole amongst others, and the respondents described wholeness of personhood as involving physical, emotional, intellectual, social, and spiritual aspects of human experience.

Subthemes of transformation, loss and isolation, and suffering were associated with the theme of wholeness. Illness, according to Cassell, “denies most conceptions of what it means to be yourself.” Losses in capacity, “when you can’t do the things you used to do,” as Saunders observed, isolate the ill by compromising those connections supporting perceptions of wholeness. “We find we are not enough,” Hammerschlag noted. “It’s too isolating. It’s too disconnecting. The nature of the human experience is not solitary.” Ill patients experience a transformation in their sense of wholeness characterized by loss and isolation. Not being the persons they have known themselves to be, they suffer.

The study respondents did not associate wholeness with physical health or cure of disease. “You can find a degree of wholeness as a person,” Saunders observed, “whether you get better or not, whether you are suffering or not, and I certainly have seen people finding a wholeness as they die.” Inui emphasized that he was “resisting the notion that healing was curing or fixing,” whereas Siegel maintained that “you can be healed and still have a physically sick body.” Hammerschlag concurred, saying that “… it’s possible to be in health and to be healed without being cured.” “As far as I can see,” Cassell noted, “you can heal somebody. You can be complete about it. I’m not convinced that you make a bit of difference in the bodily disease.” Thus, healing is independent of illness, impairment, cure of disease, or death.

Narrative

Two definitions reflected the theme of healing as a narrative. Inui clarified that his definition opposed the concept of “physicians [as] biomedical experts who identify vulnerability and disease and then, by showing up vulnerability and by eradicating disease, assure health.” Siegel noted that healing is “a reinterpretation, in a sense, of life.” For these respondents, healing occurs within the life narrative of the person experiencing the phenomena.

Narrative subthemes involved a personal connection within the context of continuity of care. Healing is related to wholeness, and wholeness is experienced in connection with others. Illness can facilitate connection. Saunders recalled a patient who described this process as “bringing together illness … patient with patient, patient with family, patient with staff.” Hammerschlag noted: “A healer is somebody who’s going to help you make those connections between each other and everything around you.” Inui described healing as occurring in contexts of “real persons in connection with other real persons,” and Cassell maintained that “to be whole is always to be whole in the presence of others.” Life narratives are social constructions, stories fashioned in connection with others.

Continuity of care supports connection. “There’s a coterie of patients through continuity of care that do come to have a special relationship with the doctor,” Stephens noted, “and I think healing is more apt to occur under those circumstances.…” Through continuity, both patient and physician come to know one another as persons. “You are missing something, as well as the patient missing something,” Saunders emphasized, “unless you come not merely in a professional role but in a role of one human being meeting another.” Stephens maintained that “you have to know your patients in some meaningful way.” Continuity, according to Inui, facilitates “incredible shortcuts you can take once you really have a strong relationship with somebody.” In the process of healing, the physician becomes part of, is connected to, the patient’s life narrative.

“Bringing together” involves sharing vulnerability, which creates safety and fosters personal connection. Medicine, Inui observed, is done “in a highly interpersonal manner” in which “people do take risks with one another … in order to be as powerful as possible in the process of sustaining health.” “When you become vulnerable and open,” Siegel maintained, “then they (patients) do because they know it’s safe.…” This type of sharing allows the patient to lay down his or her burdens and begin the process of developing a new life narrative that incorporates the experience of brokenness. “Until they’ve (patients) told you the story,” Cassell noted, “they can not reconstitute.” Inui observed that personal connection helps reduce the “loneliness that people feel.” Narratives of healing are created in close physician-patient relationships that are personal in nature and supported by continuity of care.

Spirituality

Two definitions emphasized the theme of spirituality. Stephens described the spiritual as “the will, the emotions, the meanings, the intimate relationships of a person’s life that are more than the machinery of the body.” Hammerschlag emphasized “a harmony” between mind, body, and spirit, with spirit being the “ineffable quality that we have that propels us forward.” For Hammerschlag, harmony occurs “when what you know, and what you say, and what you feel are in balance.” With harmony comes health; therefore, spirituality is an important aspect of healing.

Subthemes illuminating the theme of spirituality involved meaning, reconciliation, and transcendence. Patients experiencing healing were described as seeking or discovering meaning in their afflictions. “You learn why you’re here,” Siegel noted. Saunders observed that the spiritual involves “the search to be human.” “You read pathographies of people,” Cassell observed, “almost universally … illness awakened them to a meaning of what’s important in life, right? And if illness did that to them, we have to presume they didn’t know that beforehand.” Hammerschlag observed, “Healing has as much to do with how you come to what it is you’ve got as what it is you’ve got. How you come to it is at least as important as to whatever it is that comes to you.”

The discovery of meaning in the illness experience helps patients reconcile their distress and leads to a transcendence of suffering. Saunders described this process as “things fall into place” and observed that dying patients who had experienced healing were “quietly accepting it with the heart.” “‘I can’t see round the next bend,’ she recalled a patient telling her, ‘but I know it will be all right.’” Inui maintained: “If you look at what healers do in traditional cultures, they’re not fix-it men.… They also help people to live with it, derive meaning from … this experience of distress.”

Kubler-Ross associated suffering with the development of spirituality. “Nothing is a faster teacher,” she noted, “than suffering. The more we suffer, the earlier the spiritual quadrant opens and matures.” Stephens linked suffering with reconciliation. “Genuine reconciliation,” he said, “probably involves some kind of suffering.” Saunders described a similar process: “We do have a surprising number of people who find this capacity to reconcile family difficulties and differences and to reach the place of … an acceptance of what is happening.” Spiritual growth is the progeny of suffering and fosters reconciliation, which helps patients transcend suffering.

In summary, healing was defined in terms of developing a sense of personal wholeness that involves physical, mental, emotional, social and spiritual aspects of human experience. Illness threatens the integrity of personhood, isolating the patient and engendering suffering. Suffering is relieved by removal of the threat and restatement of the previous sense of personhood. Suffering is transcended when invested with meaning congruent with a new sense of personal wholeness. Wholeness of personhood is facilitated through personal relationships that are marked by continuity. Thus understood, the central story line of this cohort’s responses provides an operational definition of healing: Healing is the personal experience of the transcendence of suffering.

DISCUSSION

Themes of wholeness, narrative, and spirituality are congruent with the derivation of the term “healing.” Heal means “to make sound or whole” and stems from the root, haelan, the condition or state of being hal, whole.31 Hal is also the root of “holy,” defined as “spiritually pure.”31 Derivation from the same medieval root indicates a centuries-old association between healing and perceptions of wholeness and spirituality that challenges biomedical thinking. Medicine has no model of what it means to be whole as a person,32 values objective more than subjective data,33 and gives negligible consideration to spirituality.34 Though true to the derivation of the word, these themes fail to illumine the operations of healing to help clinicians better facilitate the process.

The operational definition that is the central story line of this study resolves some of this dilemma. Ill persons undergo transformations in which they are unable to be the persons they once were. This threat to wholeness generates suffering35 and involves the physical, social, psychological, and spiritual dimensions of personhood described in this study.36 Suffering is an inherently unpleasant experience reflecting perceptions of helplessness.37 It may involve pain, but it is an anguish of a different order from pain38,39 that alienates the sufferer from self and society.40 Suffering engenders a “crisis of meaning,”36 a spiritual consideration of life’s ultimate importance,34 and it is reflected as an intensely personal narrative.41 Thus, suffering subsumes the themes of wholeness, narrative, and spirituality and has major implications for facilitating healing.

Although suffering may be resolved if the threat to wholeness is removed, distress is relieved, and integrity is reinstated, the ability of medicine to resolve suffering is limited. Suffering is inherent to human experience,42 and some types of suffering are beyond the purview of medicine.44 Still, suffering can be transcended by accepting the necessity to suffer42 and by finding meaning in the threatening events.44 “Suffering ceases to be suffering in some way,” Frankl observed, “at the moment it finds a meaning.”45

Sharing suffering creates interpersonal meaning and melds the life stories of patient and physician.46 Creating interpersonal meaning and melding life stories produce a connexional relationship, a “mutual experience of joining that results in a sensation of wholeness.”47 Connexional relationships reduce the alienation of suffering. As the physician becomes a part of patients’ life narratives and “experiences with” them,40,41,48–50 patients no longer suffer alone. Patients can use this intimate, transpersonal context to “edit” their life stories.51 By reconstructing identity, reforming purpose, and revising their life narratives to accept or find meaning and transcend suffering,52,53 patients experience healing.

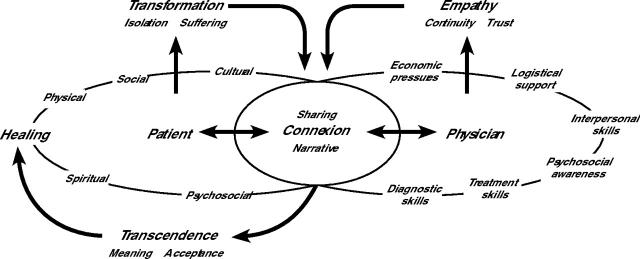

The role of the physician-healer is to establish connexional relationships with his or her patients and guide them in reworking of their life narratives to create meaning in and transcend their suffering.53,54 Even though it is the patient who must find the meaning that transcends his or her suffering, the physician can catalyze this process by sensitively attending to and engaging the patient in dialogue regarding the patient’s suffering. This process is depicted in Figure 1 ▶.

Figure 1.

The healing process.

Unfortunately, medicine does little to prepare physicians to guide sufferers.56,57 Physicians are not trained to hear patients’ stories, often fail to solicit the patient’s agenda or pick up on a patient’s clues, and often limit storytelling to maintain diagnostic clarity, support efficiency, and avoid confusion and unpleasant feelings.58–62 How to comfort the sick or hear sensitive patient disclosures is often left to common sense.63,64 Empathy offered inopportunely, however, exacerbates distress, and inordinately emphasizing biomedical data delegitimizes the suffering contained in the patient’s story.41,65,66 Some physicians question the legitimacy of being a guide for patients or find the moral authority associated with the role uncomfortable, whereas others fear the intense feelings encountered on the healing journey.48,53 Not knowing how to engage suffering risks iatrogenically inducing it.

Yet changes in medicine reflect progress in addressing holistic perspectives that conceivably might augment physician attempts to effect healing. Increasing research on the potential impacts of spirituality and religion on health outcomes67–71 has stimulated a vigorous dialogue regarding the place of spirituality in medicine.72–74 Nearly one half of medical schools in the United States now offer courses on spirituality in medicine, and all teach interviewing and interpersonal skills.68,75 Patient-centered approaches to clinical care are having positive impacts on the patient-physician relationship and health outcomes,76–78 and curricula for teaching patient-centered communication are extending into the clinical years of training.79–81 Conceivably, these efforts will better prepare physicians to establish connexional relationships, explore patients’ life narratives, and help patients finding meaning in their experience to transcend their suffering.

This study is subject to both methodologic and contextual limitations. It is the product of a single researcher doing an individual analysis of data obtained from a small sample of Western-trained allopathic physicians. Interviews with a larger group of physicians—especially those from other healing traditions—with analysis by multiple researchers would likely produce different results. Likewise, interviews with patients who considered themselves to have experienced healing would be enlightening and undoubtedly change the study results. The validity of the data presented is inherently intuitive. Congruent with the subjective nature of the phenomena of inquiry, readers must judge the generalizability of this study by their own experience.

That the proposed definition of healing relies heavily upon issues of meaning, spirituality, and the physician-patient relationship for its operations is a limitation. The lack of precise definitions for spirituality inhibits systematic research in this area.71 Conceivably, those patients who do not wish to discuss their spirituality, who are mentally incapacitated, or who are incapable of or disinterested in a connexional relationship might not be amenable to the operations of healing described herein. Whether healing in some other guise occurs for these patients is a plausible question for further study, but it could be that healing, as is cure of disease, is not possible for all patients. For all these reasons, the definition of healing proffered in this study must be considered provisional, but it provides a good starting point for further discussion and study.

The industrialization of health care in the United States may render the results of this study superfluous.82 The episodic contact patients often have with subspecialty physicians undermines the trust generated by continuity of care83 that might be necessary for connexional relationships to form. The economics of primary care practice force patient volumes in time increments that make the intimate connection necessary for healing difficult. That healing remains a core function of medicine is questionable, because modern medicine focuses on the efficient dispersal of biomedical services, not healing. Still, patient care remains a core function.

“The secret of the care of the patient,” Peabody noted, “is caring for the patient.”84 Caring relationships are founded to foster personal growth.85 Transcending suffering is surely personal growth. By forging connexional relationships, grounding treatment choices in the person rather than the disease, maximizing function, and actively minimizing suffering, physicians strengthen patients with the goal of maintaining intactness and integrity.48,86–88 The requisite clinical methods, empathy, and communication skills for fostering connexional relationships are known and teachable,89–93 and the necessary attitudes and insight are being discussed.94–97 Still, research regarding the detection and management of suffering is sorely needed. By helping patients transcend suffering, physicians surpass their curative roles to claim their heritage as healers. In the process, medicine recapitulates its service ethic as “a work of the heart and soul”98 and maintains its tradition as a healing profession.

Acknowledgments

The author extends deep appreciation to the study participants whose generous gifts of time, clarity of thought, and passion for healing made this study possible. The author also wishes to thank Drs. Stuart J. Farber, Joan E. Halley, Kevin F. Murray, and Thomas E. Norris for their thoughtful review of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: none reported

REFERENCES

- 1.Starr P. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1982.

- 2.Ludmerer KM. Learning to Heal. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1985.

- 3.Toulmin S. On the nature of the physician’s understanding. J Med Philos. 1976;1:32–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cassell EJ. The Healer’s Art. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press; 1976.

- 5.Hauerwas S. Naming The Silences: God, Medicine, and the Problem of Suffering. Grand Rapids, Mich: Wm. B. Eerdsman Publishing Co; 1990.

- 6.Csordas TJ, Kleinman A. The therapeutic process. In: Medical Anthropology: Contemporary Theory And Method. Johnson TM, Sargent CF, ed. New York, NY: Praeger Publishers; 1990.

- 7.Comfort A. On healing Americans. J Operational Psychiatry. 1978;9: 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon R. Reflections on curing and healing. J Anal Psychol. 1979; 24:207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinn JF. The self as healer: reflections from a nurse’s journey. AACN Clin Issues. 2000;11:17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson C. Healing ourselves, healing others: first in a series. Holist Nurs Pract. 2004;18:67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dossey BM, Keegan L, Guzzetta CE, eds. Holistic Nursing: A Handbook for Practice. 4th ed. Sudbury, Mass: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2005.

- 12.Dossey L. Whatever Happened to Healers? Altern Ther Health Med. 1995;1:6–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weil A. Health And Healing. Boston, Mass: Houghton Mifflin; 1983.

- 14.Dorland’s Illustrated Medical Dictionary. 25th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1974.

- 15.Benjamin WW. Healing by the fundamentals. N Engl J Med. 1984; 311:595–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lown B. The Lost Art of Healing. Boston, Mass: Houghton Mifflin; 1996.

- 17.Murray RH, Rubel AJ. Physicians and healers--unwitting partners in health care. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:61–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleinman AM. Some issues for a comparative study of medical healing. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1973;19:159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reilly D. Enhancing human healing. BMJ. 2001;322:120–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. A qualitative approach to primary care research: the long interview. Fam Med. 1991;23:145–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spradley JP. The Ethnographic Interview. New York, NY: Rinehardt & Winston; 1979.

- 22.Egnew TR. On Becoming a Healer: A Grounded Theory [dissertation]. Seattle, Wash: Seattle University; 1994.

- 23.Patton MQ. How To Use Qualitative Methods in Evaluation. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1987.

- 24.Marshall C, Rossman GB. Designing Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1989.

- 25.McCracken G. The Long Interview. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1988.

- 26.Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000;320:50–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seidel JV, Kjolseth R, Seymour E. The Ethnograph (v 3). Corvallis, Ore: Qualis Research Associates; 1988.

- 28.Strauss A, Corbin C. Basics of Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1990.

- 29.Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. New York, NY: Aldine; 1967.

- 30.Wolcott HF. Writing Up Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1990.

- 31.Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary. Springfield, Mass: G & C Merriam Company; 1979.

- 32.Cassell EJ. The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1991.

- 33.Eisenberg L. The subjective in medicine. Perspect Biol Med. 1983;27:48–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hiatt JF. Spirituality, medicine, and healing. South Med J. 1986;79:736–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cassell EJ. Recognizing suffering. Hastings Cent Rep. 1991;21:24–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barrett DA. Suffering and the process of transformation. J Pastoral Care. 1999;53:461–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chapman CR, Gavrin J. Suffering and its relationship to pain. J Palliat Care. 1993;9:5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donnelly WJ. Taking suffering seriously: a new role for the medical case history. Acad Med. 1996;71:730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macleod R. The pain of it all. N Z Fam Pract. 2004;31:65–66. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Younger JB. The alienation of the sufferer. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1995;17:53–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reich WT. Speaking of suffering: a moral account of compassion. Soundings. 1989;72:83–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia. Buddhism. 2004. Available at: http://encarta.msn.com. Accessed: February 18, 2004.

- 43.Fleischer TE. Suffering reclaimed: medicine according to Job. Perspect Biol Med. 1999;42:475–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brody H. Stories of Sickness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1987.

- 45.Frankl VE. Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy. New York, NY: Pocket Books; 1963.

- 46.Gadow G. Suffering and interpersonal meaning: commentary. J Clin Ethics. 1991;2:103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suchman AL, Matthews DA. What makes the patient-doctor relationship therapeutic? Exploring the connexional dimension of medical care. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Hooft S. Suffering and the goals of medicine. Med Health Care Philos. 1998;1:125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gunderman RB. Is suffering the enemy? Hastings Cent Rep. 2002;32: 40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pellegrino ED. The healing relationship: the architronics of clinical medicine. In: Shelp EA, ed. The Clinical Encounter: The Moral Fabric of the Physician-Patient Relationship. Dordrecht Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Co; 1983:153–172.

- 51.Farber SJ, Egnew TR, Farber A. What is a respectful death? In: Berzoff J, Silverman PR, eds. Living With Dying: A Handbook for End-Of-Life Healthcare Practitioners. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2004:102–127.

- 52.Stuart MR, Lieberman JAI. The Fifteen Minute Hour: Applied Psychotherapy for the Primary Care Physician. 2nd ed. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 1993.

- 53.Verhey A. Compassion: beyond the standard account. Second Opin. 1992;18:99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nuland SB. How We Die. New York, NY: Alfred A, Knopf; 1994.

- 55.Farber SJ, Egnew TR, Herman-Bertsch JL. Defining effective clinician roles in end-of-life care. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wanzer SH, Federman DD, Adelstein SJ, et al. The physician’s responsibility toward hopelessly ill patients. A second look. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:844–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gavrin J, Chapman CR. Clinical management of dying patients. West J Med. 1995;163:268–277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hunter KM. Doctor’s Stories: The Narrative Structure of Medical Knowledge. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1991.

- 59.Waitzkin H. The Politics of Medical Encounters: How Patients and Doctors Deal With Social Problems. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1991.

- 60.Marvel MK, Epstein RM, Flowers K, Beckman HB. Soliciting the patient’s agenda: have we improved? JAMA. 1999;281:283–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA. 1997;277:678–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levinson W, Gorawara-Bhat R, Lamb J. A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. JAMA. 2000;284:1021–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Balint M. The Doctor, His Patient and the Illness. Rev ed. New York, NY: International Universities Press; 1964.

- 64.Hilfiker D. Healing the Wounds. New York, NY: Pantheon Books; 1985.

- 65.Morse JM. Toward a praxis theory of suffering. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2001;24:47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kleinman A, Kleinman J. Suffering and its professional transformation: toward an ethnography of interpersonal experience. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1991;15:275–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Byrd RC. Positive therapeutic effects of intercessory prayer in a coronary care unit population. South Med J. 1988;81:826–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McBride JL, Arthur G, Brooks R, Pilkington L. The relationship between a patient’s spirituality and health experiences. Fam Med. 1998;30:122–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Matthews DA, McCullough ME, Larson DB, et al. Religious commitment and health status: a review of the research and implications for family medicine. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Daaleman TP, Perera S, Studenski SA. Religion, spirituality, and health status in geriatric outpatients. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:49–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sloan RP, Bagiella E, Powell T. Religion, spirituality, and medicine. Lancet. 1999;353:664–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Koenig HG, Idler E, Kasl S, et al. Religion, spirituality, and medicine: a rebuttal to skeptics. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1999;29:123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sulmasy DP. Is medicine a spiritual practice? Acad Med. 1999;74:1002–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Novack DH, Volk G, Drossman DA, Lipkin M, Jr. Medical interviewing and interpersonal skills teaching in US medical schools. Progress, problems, and promise. JAMA. 1993;269:2101–2105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ. 2001;323:908–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Krupat E, Bell RA, Kravitz RL, Thom D, Azari R. When physicians and patients think alike: patient-centered beliefs and their impact on satisfaction and trust. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:1057–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Oh J, Segal R, Gordon J, Boal J, Jotkowitz A. Retention and use of patient-centered interviewing skills after intensive training. Acad Med. 2001;76:647–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yedidia MJ, Gillespie CC, Kachur E, et al. Effect of communications training on medical student performance. JAMA. 2003;290:1157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Egnew TR, Mauksch LB, Greer T, Farber SJ. Integrating communication training into a required family medicine clerkship. Acad Med. 2004;79:737–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rastegar DA. Health care becomes an industry. Ann Fam Med. 2004; 2:79–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mainous AG, 3rd, Baker R, Love MM, Gray DP, Gill JM. Continuity of care and trust in one’s physician: evidence from primary care in the United States and the United Kingdom. Fam Med. 2001;33:22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Peabody FW. The care of the patient. JAMA. 1927;88:877–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mayeroff M. On Caring. New York, NY: Harper Perennial; 1990.

- 86.Cassell EJ. The relief of suffering. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:522–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cassell EJ. The nature of suffering: physical, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects. NLN Publ. 1992:1–10. [PubMed]

- 88.Cassell EJ. Diagnosing suffering: a perspective. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:531–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Charon R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286:1897–1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zinn W. The empathic physician. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:306–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kurtz S, Silverman J, Draper J. Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine. Abingdon, UK: Radcliffe Medical Press; 1998.

- 92.Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, et al. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress. A randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1877–1884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, McWhinney IR, Freeman TR. Patient-Centered Medicine. Transforming the Clinical Method. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1995.

- 94.Novack DH, Suchman AL, Clark W, et al. Calibrating the physician. Personal awareness and effective patient care. Working Group on Promoting Physician Personal Awareness, American Academy on Physician and Patient. JAMA. 1997;278:502–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Novack DH, Epstein RM, Paulsen RH. Toward creating physician-healers: fostering medical students’ self-awareness, personal growth, and well-being. Acad Med. 1999;74:516–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999;282:833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.LeBaron S. Can the future of medicine be saved from the success of science? Acad Med. 2004;79:661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Remen RN. Recapturing the soul of medicine: physicians need to reclaim meaning in their working lives. West J Med. 2001;174:4–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]