Abstract

Solid state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) has developed into one of the most informative and direct experimental approaches to the characterization of the molecular structures of amyloid fibrils, including those associated with Alzheimer's disease. In this article, essential aspects of solid state NMR methods are described briefly and results obtained to date regarding the supramolecular organization of amyloid fibrils and the conformations of peptides within amyloid fibrils are reviewed.

Keywords: amyloid structure, Alzheimer's disease, prions, protein aggregation, magnetic resonance

Introduction

The molecular structures of amyloid fibrils are of considerable current interest, as structural information is essential for an understanding of the interactions that drive amyloid formation, for a realistic understanding of fibrillization mechanisms and pathways, and for the design and understanding of fibrillization inhibitors. However, because amyloid fibrils are inherently insoluble and noncrystalline, conventional experimental approaches to biomolecular structure determination such as x-ray crystallography and multidimensional liquid state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) are of limited value in the amyloid field. Solid state NMR, meaning a class of NMR methods developed specifically for structural studies of biochemical (and other) systems in noncrystalline solid and solid-like states, has emerged as a principal methodology for structural studies of amyloid fibrils in the past decade [1-3]. Solid state NMR measurements have provided answers to central questions concerning the supramolecular organization of amyloid fibrils [4-16], peptide conformations within amyloid fibrils [6,8,10,11,17-23], and the diversity of amyloid structures [10-15,24]. Solid state NMR data have been used as the primary basis for experimentally-constrained structural models of amyloid fibrils, including fibrils formed by the 40-residue β-amyloid (Aβ1-40) peptide associated with Alzheimer's disease [11,22] and by shorter peptides derived from Aβ1-40 or other amyloid-forming proteins [4,5,7,8,10,14,16,25]. Basic aspects of solid state NMR measurements and results obtained for various types of amyloid fibrils are discussed below.

Basic principles of solid state NMR

Several types of solid state NMR measurements have been useful in structural studies of amyloid fibrils: (1) Isotropic 13C chemical shifts correlate strongly with secondary structure [26-30], allowing the locations of β-strand segments and other secondary structure elements within a peptide sequence to be determined. It has proven particularly valuable to measure the chemical shifts of many carbon sites simultaneously in two-dimensional (2D) 13C-13C correlation spectra of amyloid samples that contain multiple uniformly 15N,13C-labeled residues [10,20,22,31]; (2) Solid state NMR linewidths indicate the degree of structural order at a site-specific level, as static variations in conformation and inter-residue contacts produce variations in chemical shifts that typically are the dominant source of line broadening in rigid noncrystalline materials. Based on empirical observations [32-34], 13C NMR linewidths of approximately 2.5 ppm or less indicate a well-defined conformation in a noncrystalline environment. Broader lines indicate greater disorder. Thus, structurally ordered and disordered segments within an amyloid fibril can be determined from solid state NMR spectra [9,22]; (3) Nuclear magnetic dipole-dipole couplings depend on interatomic distances as 1/R3, allowing distances between specific pairs of carbon and/or nitrogen atoms to be determined, up to a limit of about 0.6 nm and with a precision of approximately 10%. Such distance measurements, which can constrain supramolecular organization [4-13,15,16] or molecular conformation [6,8,17-19,21-23], can be carried out on samples with labels at specific sites [4-12,15-19,23] or with multiple uniformly labeled residues [13,21,22] (4) Quantitative constraints on backbone and sidechain torsion angles can be obtained from ″tensor correlation″ techniques, i.e., solid state NMR measurements that are sensitive to the relative orientations of two chemical functional groups and/or bond directions [19,35-45]. Again, these techniques can be applied to amyloid samples with specific-site labels [23] or with uniformly labeled residues [21,45]; (5) Tertiary and quaternary contacts involved in β-sheet structure or other aspects of supramolecular organization can be identified from nonsequential or intermolecular crosspeaks in 2D 13C-13C exchange techniques that rely on spin diffusion among the labeled carbon sites or among directly bonded hydrogens [13,14].

The techniques mentioned above are usually used in combination with magic-angle spinning (MAS), i.e., rapid sample rotation about an axis at the angle to the external magnetic field, which produces a dramatic enhancement of resolution and sensitivity in solid state 13C and 15N NMR by averaging out chemical shift anisotropies and dipole-dipole couplings. To restore the relevant dipole-dipole couplings in distance measurements, tensor correlation measurements, and 2D correlation measurements, radio-frequency pulse sequences (called ”dipolar recoupling” techniques [31,46-55]) are applied in synchrony with the sample rotation. The techniques mentioned above have been applied to amyloid fibril samples that are either in a hydrated or in a lyophilized state and are not aligned. In our laboratory, 13C NMR spectra of hydrated and lyophilized amyloid fibrils exhibit identical chemical shifts and only minor differences in linewidths [14], especially for structurally ordered sites. Recently, we have demonstrated that solid state NMR measurements on aligned amyloid fibrils, prepared by drying fibril solutions on planar substrates such as mica, provide useful structural information in the form of constraints on the orientation of 13C-labeled chemical groups relative to the fibril axis [56].

Several practical considerations contribute to the success of solid state NMR studies of amyloid fibrils: (1) The structures are generally well-ordered, leading to relatively sharp NMR lines and high-quality spectra. In fact, the observation of relatively sharp solid state NMR lines proves that amyloid fibrils are not highly disordered at the molecular level, a fundamental aspect of their properties that would not be clear from other experimental measurements; (2) Biomedically significant amyloid-forming peptides, including Aβ1-40 and amylin, are small enough that they can be synthesized by automated solid phase methods in high yield, allowing isotopic labeling of specific sites or specific residues, depending on the requirements of the measurement; (3) Amyloid fibril samples are highly concentrated, either as lyophilized powders or as centrifuged pellets. The sample quantity required for adequate experimental signal-to-noise, typically 0.2-2 μmol for measurements near room temperature with modern hardware, can therefore be contained in a 10-100 μl volume. This permits high-speed MAS and high radio-frequency fields, facilitating many measurements and generally enhancing the quality of the data. In contrast, solid state NMR measurements on membrane proteins or frozen protein solutions often necessarily involve lower protein concentrations and larger volumes, making those measurements more difficult.

Results from solid state NMR

The first solid state NMR studies of amyloid fibrils were performed by Griffin, Lansbury, and coworkers [4,17-19]. In particular, they applied dipolar recoupling techniques to samples of Aβ34-42 fibrils (where Aβn-m represents residues n through m of the full-length β-amyloid sequence) prepared with pairs of 13C labels and obtained constraints on both the peptide conformation and the intermolecular alignment within the β-sheets of these fibrils. From these constraints, they developed a structural model for Aβ34-42fibrils that includes antiparallel β-sheets with an alternating hydrogen bond registry [4]. Subsequently, Lynn, Meredith, Botto, and coworkers carried out extensive studies of Aβ10-35 fibrils, applying dipolar recoupling techniques to singly- and doubly-labeled samples to obtain constraints on β-sheet organization and peptide conformation [5-8]. These studies of Aβ10-35 fibrils were the first to reveal the parallel, in-register β-sheet organization that has since been found in other systems and is now widely believed to be the most common (but not universal) β-sheet organization in amyloid fibrils [9,11,12,25,57-62], especially for fibrils formed by relatively long polypeptide chains.

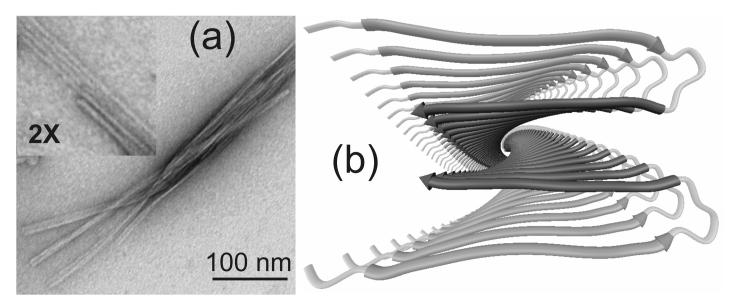

Stimulated by these earlier results, my laboratory has undertaken solid state NMR studies of fibrils formed by the full-length β-amyloid peptides Aβ1-40 [9,12,22-24,56] and Aβ1-42 [11], and by the fragments Aβ16-22 [10,13] and Aβ11-25 [13,14], employing all of the techniques and structural parameters discussed above. Constraints available in 2002 were used to develop the structural model for Aβ1-40 fibrils [1,2,22] depicted in Figure 1. Although certain aspects of this model are not yet determined uniquely by experimental constraints [22], the model is also largely consistent with data from non-NMR techniques [63-66] and shows explicitly how a structure with apparently favorable hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions can be formed by full-length β-amyloid. Independently, a model for Aβ10-35 fibrils very similar to our published model for Aβ1-40 fibrils was proposed by Ma and Nussinov [67] and shown to be stable in water over the course of a 1.2 ns molecular dynamics simulation. There is reason to believe that the molecular structures of fibrils formed by unrelated peptides and proteins may also resemble the model in Figure 1 in certain respects, especially the formation of a double-layered (or multilayered) cross-β motif by a single layer of molecules [25,68,69].

Figure 1.

(a) Transmission electron microscope image of Aβ1-40 fibrils, negatively stained with uranyl acetate. Fibrils were grown at 25° C, pH 7.4, 10 mM phosphate buffer, 210 μM peptide concentration, with gentle agitation [11,22,24]. Fibrils appear to be comprised of finer protofilaments, with diameters of approximately 5 nm. (b) Ribbon representation of a structural model for the Aβ1-40 protofilament, based on solid state NMR and electron microscopy data [2, 22], viewed along its long axis. The β-sheets in the cross-β motif are parallel and in-register, and are formed by two β-strand segments from each Aβ1-40 molecule (medium and darkest gray segments) that are separated by a loop (lightest gray segment). Two molecular layers form a four-layered structure with a predominantly hydrophobic core.

Elevated levels of the 42-residue version of the β-amyloid peptide (Aβ1-42) in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma are observed in familial and sporadic forms of Alzheimer's disease [70]. The limited number of solid state NMR measurements carried out on Aβ1-42 to date indicate that the structure of Aβ1-42 fibrils is not qualitatively different from that of Aβ1-40 fibrils [11]. In addition, Aβ1-42 has been shown to cofibrillize with Aβ1-40, with molecular-level mixing of the two peptides within individual fibrils [66]. Thus, the available experimental evidence suggests that the association of Aβ1-42 with Alzheimer's disease does not have a simple and exclusive basis in fibril structure.

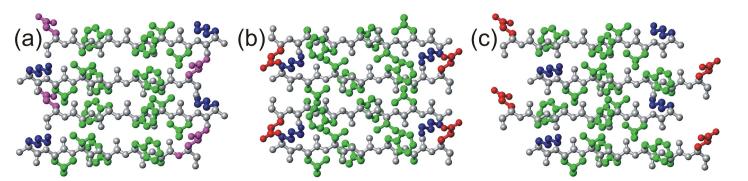

Our data on Aβ16-22 fibrils [10,13] and Aβ11-25 fibrils [14] indicate the antiparallel β-sheet structures shown in Figure 2. To date, antiparallel β-sheet structures have been identified only in fibrils formed by relatively short peptides, which contain only one β-strand segment. It is particularly interesting that the precise registry of hydrogen bonds in these structures is not determined uniquely by amino acid sequence at the level of 7-residue or 15-residue segments, indicating that studies of model peptides can not generally be used to infer structural properties of full-length amyloid-forming sequences. It is also interesting that pH-dependent variations in registry are observed, indicating that the registry is determined by a balance of hydrophobic, electrostatic, and possibly other intermolecular interactions. Finally, it is interesting that ”registry-shift” defects and coexistence of distinct registries have not been detected in our solid state NMR data [13,14], despite the fact that various registries are possible and presumably have similar free energies. Assuming that the fibrils grow primarily by addition of monomeric or oligomeric peptides to their ends, the absence of detectable defects in the β-sheet organization suggests that a structural annealing process occurs at the ends, which may be a rate-limiting step for fibril growth [71].

Figure 2.

Antiparallel β-sheet structures determined by solid state NMR for fibrils formed by Aβ11-25 at pH 2.4, Aβ16-22 at pH 7.4, and Aβ11-25 at pH 7.4 (a-c, respectively). Residues 16-22 are shown in each case (amino acid sequence KLVFFAE). Hydrophobic, negatively charged, positively charged, and polar sidechains are colored green, red, blue, and magenta, respectively. Sidechain conformations are chosen arbitrarily. The same seven-residue segment adopts three different and highly-ordered registries of backbone hydrogen bonding, depending on the full sequence and on pH. (Figure generated with MOLMOL [96].)

In a recent collaboration between Cambridge groups (in Massachusetts and England), Jaroniec et al. [20,21] developed a high-resolution model for the full molecular conformation in fibrils formed by residues 105-115 of transthyretin (TTR105-115). This model is based on a large set of chemical shift, distance, and torsion angle constraints, analyzed in a manner similar to that used in liquid state NMR to determine structures of soluble proteins. These studies demonstrate many of the capabilities of state-of-the-art solid state NMR methods.

A solid state NMR study of fibrils formed by the designed 17-residue peptide ccβ was recently reported by Kammerer et al. [16]. The ccβ peptide was designed to form a trimeric helical coiled-coil structure, as verified by x-ray crystallography [16], but was also found to form amyloid fibrils at elevated temperatures in an apparently irreversible structural conversion. Measurements of 15N-13C dipole-dipole couplings in selectively isotopically labeled samples support an antiparallel β-sheet structure in ccβ fibrils, apparently stabilized by both hydrophobic and electrostatic intrasheet interactions. Kammerer et al. proposed a model for intersheet contacts, which also involve favorable hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions, but this model has not yet been verified by solid state NMR data.

Laws et al. [72] have reported solid state NMR studies of synthetic peptides representing residues 89-143 of mammalian prion proteins (PrP89-143). In these studies, one-dimensional 13C MAS NMR spectra of selectively labeled samples prepared by slow fibrillization in an acetonitrile/water buffer and by more rapid drying in air were compared. Differences in β-sheet content revealed by 13C NMR chemical shifts were used to assess the relative propensities of the mouse-derived and Syrian hamster-derived sequences to form β-sheet aggregates. The solid state NMR results correlated well with biological observations regarding the ability of these peptides to induce prion-like diseases, and with the effects of specific mutations on the biological results.

High-quality electron microscope (EM) and atomic force microscope images of amyloid fibrils commonly show several distinct fibril morphologies, all formed by the same peptide or protein [68,73-76]. It has been unclear whether distinct morphologies arise from significant variations in molecular structure within protofilaments (i.e., filamentous subunits that associate to form the observed fibril), or merely from variations in the mode of association of protofilaments. Cryo-EM images have been presented by Jimenez et al. as evidence for a single protofilament structure in insulin fibrils with diverse morphologies [68]. However, recent solid state NMR and EM experiments on Aβ1-40 fibrils in our laboratory show that morphological differences correlate with underlying differences in molecular structure at the protofilament level [24]. In these experiments, fibril growth conditions (termed ”quiescent” and ”agitated”) that lead to distinct predominant morphologies were discovered. Quiescent and agitated Aβ1-40 fibrils were found to have significantly different sets of 13C chemical shifts, differences in tertiary contacts identified from dipolar recoupling data, and differences in protofilament mass-per-length (MPL). The morphological and structural features were found to propagate together when preformed fibrils were used as seeds to generate subsequent samples. These results support the proposal that distinct strains of mammalian and yeast prion diseases may arise from structurally distinct and self-propagating amyloid-like forms of prion proteins [77-81]. In our experiments, quiescent and agitated fibrils were also found to have significantly different toxicities in cultures of primary rat embryonic hippocampal neurons [24]. Perhaps amyloid diseases such as Alzheimer's disease also have ”strains”, i.e., certain amyloid structures may be more effective than others at producing disease symptoms in humans.

Some implications of the solid state NMR results

Solid state NMR data reveal that amyloid fibrils, particularly those formed by relatively short peptides, can have a level of structural order approaching that in a protein crystal. The strongest evidence for this is the observation of 13C and 15N linewidths in the 0.5-1.5 ppm range under MAS for TTR105-115 and Aβ11-25 fibrils [14,21]. X-ray diffraction and cryo-EM studies of Aβ11-25 fibrils also indicate a very high level of structural order [82,83]. In fibrils formed by longer peptides such as Aβ1-40, structurally ordered segments coexist with disordered segments [9,22,24]. Disorder within amyloid fibrils can be continuous (i.e., population of a continuous range of backbone or sidechain conformations within a single fibril for certain residues, leading to broad MAS NMR lines for these residues) or discrete (e.g., population of two distinct backbone or sidechain conformations, possibly within a single fibril, leading to two sets of MAS NMR lines for certain residues). As discussed above, the supramolecular organization within the β-sheets in amyloid fibrils is remarkably well ordered. No evidence for mixed parallel/antiparallel structures or for detectable levels of defects in the registry of intermolecular backbone hydrogen bonds has been reported to date.

Although amyloid fibrils have well-defined molecular structures, their structures can also exhibit considerable plasticity. As exemplified by the findings for Aβ1-40 fibrils discussed above [24], a single amino acid sequence can give rise to fibrils with multiple distinct morphologies and underlying molecular structures. Subtle variations in growth conditions, even at fixed temperature, pH, ionic strength, buffer composition, and peptide concentration, can favor one structure over another. This is presumably because the fibril structure is dictated by a nucleation event (i.e., an infrequent fluctuation in structure or oligomerization state, not yet understood in detail, that creates a peptide aggregate capable of growing to a fibril by subsequent addition of other peptide molecules), and more than one type of nucleation event is possible. Because of the structural plasticity of amyloid fibrils, it is important that fibril morphologies (e.g., in high-quality EM images) be examined carefully when one compares structural data from different research groups or different fibril samples. It is also important that one keep in mind the possibility that more than one fibril structure may be present in any structural measurement, unless structural homogeneity is established by solid state NMR (e.g., by the absence of multiple sets of 13C chemical shifts in spectra of samples with multiple uniformly labeled residues), high-resolution EM, or some other technique that is sensitive to structural variations. The structural plasticity of amyloid fibrils also complicates the interpretation of the effects of amino acid substitutions, chemical modifications, or other manipulations on the kinetics and thermodynamics of fibril formation and on biological effects (e.g., the association of particular mutations in Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 with familial forms of Alzheimer's disease [84]). Such manipulations may favor new or different nucleation events, leading to new or different structural endpoints.

The model in Figure 1 provides insight into the nature of the interactions that stabilize amyloid fibril structures. Through the combination of peptide conformation, parallel β-sheet structure, and supramolecular organization in Figure 1, the majority of hydrophobic amino acid sidechains are sequestered in the interior of the fibril. All nonhydrophobic and charged sidechains are freely accessible to aqueous solvent, with the exception of oppositely charged sidechains of Asp23 and Lys28. These sidechains form a network of salt bridges, thereby preventing the destabilization of the fibril structure through intermolecular electrostatic repulsions that one would expect if only isolated like charges were located in the hydrophobic fibril core. Thus, for full-length β-amyloid peptides, and probably for other peptides that contain hydrophobic segments, fibril formation is apparently driven by hydrophobic interactions, but it is essential that the detailed molecular structure be such that destabilizing electrostatic interactions in the fibril core are avoided [2,22].

The maximum length of continuous β-strand segments within amyloid fibrils appears to be roughly ten residues, based on reported solid state NMR data [22,24] and substantiated by results from other techniques [65,66,85,86]. Longer β-strand segments might be destabilized by the tendency of the peptide backbone to twist, preventing optimal interstrand hydrogen bonding geometries in longer β-strand segments [87]. When longer peptides (and bona fide proteins) form amyloid fibrils, their secondary structures are therefore likely to consist of alternating β-strand and loop (or bend, or turn) segments. This general pattern of secondary structure is contained in our Aβ1-40 structural model [11,22], as well as in earlier [68,69,88,89] and later [25,65] models for amyloid structures. This pattern of secondary structure naturally leads to a laminated β-sheet structure, as in Figure 1.

As an alternative to a laminated β-sheet structure, several groups [57-59,90-93] have proposed that certain amyloid fibrils, including fibrils formed by Aβ1-40 or Aβ1-42 [59,90,91], may contain structures that resemble those of β-helical proteins[94,95]. Aβ-helical structure with a hollow, water-filled core, as suggested by certain groups [91,93], appears inconsistent with solid state NMR data for systems studied to date, including the observation of specific intersheet contacts in Aβ1-40 fibrils and the insensitivity of 13C NMR chemical shifts in amyloid fibrils to hydration level. However, a ”flattened” β-helical structure, without a hollow core, remains a possibility for Aβ1-40 and other fibrils. This issue, as well as many other issues regarding amyloid fibril structures and the interactions that stabilize them, is likely to be settled by solid state NMR measurements in the near future.

References

- [1].Tycko R. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tycko R. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3151–3159. doi: 10.1021/bi027378p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tycko R. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2003;42:53–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2023.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lansbury PT, Costa PR, Griffiths JM, Simon EJ, Auger M, Halverson KJ, Kocisko DA, Hendsch ZS, Ashburn TT, Spencer RGS, Tidor B, Griffin RG. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1995;2:990–998. doi: 10.1038/nsb1195-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Benzinger TLS, Gregory DM, Burkoth TS, Miller-Auer H, Lynn DG, Botto RE, Meredith SC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:13407–13412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gregory DM, Benzinger TLS, Burkoth TS, Miller-Auer H, Lynn DG, Meredith SC, Botto RE. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 1998;13:149–166. doi: 10.1016/s0926-2040(98)00086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Burkoth TS, Benzinger TLS, Urban V, Morgan DM, Gregory DM, Thiyagarajan P, Botto RE, Meredith SC, Lynn DG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:7883–7889. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Benzinger TLS, Gregory DM, Burkoth TS, Miller-Auer H, Lynn DG, Botto RE, Meredith SC. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3491–3499. doi: 10.1021/bi991527v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Antzutkin ON, Balbach JJ, Leapman RD, Rizzo NW, Reed J, Tycko R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:13045–13050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230315097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Balbach JJ, Ishii Y, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Rizzo NW, Dyda F, Reed J, Tycko R. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13748–13759. doi: 10.1021/bi0011330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Balbach JJ, Tycko R. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15436–15450. doi: 10.1021/bi0204185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Balbach JJ, Petkova AT, Oyler NA, Antzutkin ON, Gordon DJ, Meredith SC, Tycko R. Biophys. J. 2002;83:1205–1216. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75244-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tycko R, Ishii Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003 doi: 10.1021/ja0342042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Petkova AT, Buntkowsky G, Dyda F, Leapman RD, Yau WM, Tycko R. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;335:247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gordon DJ, Balbach JJ, Tycko R, Meredith SC. Biophys. J. 2004;86:428–434. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74119-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kammerer RA, Kostrewa D, Zurdo J, Detken A, Garcia-Echeverria C, Green JD, Muller SA, Meier BH, Winkler FK, Dobson CM, Steinmetz MO. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:4435–4440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306786101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Spencer RGS, Halverson KJ, Auger M, McDermott AE, Griffin RG, Lansbury PT. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10382–10387. doi: 10.1021/bi00107a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Griffiths JM, Ashburn TT, Auger M, Costa PR, Griffin RG, Lansbury PT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:3539–3546. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Costa PR, Kocisko DA, Sun BQ, Lansbury PT, Griffin RG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:10487–10493. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jaroniec CP, MacPhee CE, Astrof NS, Dobson CM, Griffin RG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:16748–16753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252625999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jaroniec CP, MacPhee CE, Bajaj VS, McMahon MT, Dobson CM, Griffin RG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:711–716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304849101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Petkova AT, Ishii Y, Balbach JJ, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Delaglio F, Tycko R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:16742–16747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262663499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Antzutkin ON, Balbach JJ, Tycko R. Biophys. J. 2003;84:3326–3335. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70057-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Petkova AT, Leapman RD, Guo Z, Ming W-M, Mattson MP, Tycko R. Science. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kajava AV, Baxa U, Wickner RB, Steven AC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:7885–7890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402427101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Saito H. Magn. Reson. Chem. 1986;24:835–852. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Spera S, Bax A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:5490–5492. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. J. Biomol. NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;222:311–333. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90214-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wishart DS, Case DA. Methods Enzymol. 2001;338:3–34. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)38214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ishii Y. J. Chem. Phys. 2001;114:8473–8483. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Long HW, Tycko R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:7039–7048. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Weliky DP, Bennett AE, Zvi A, Anglister J, Steinbach PJ, Tycko R. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:141–145. doi: 10.1038/5827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sharpe S, Kessler N, Anglister JA, Yau WM, Tycko R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:4979–4990. doi: 10.1021/ja0392162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Weliky DP, Dabbagh G, Tycko R. J. Magn. Reson. Ser. A. 1993;104:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tycko R, Weliky DP, Berger AE. J. Chem. Phys. 1996;105:7915–7930. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Weliky DP, Tycko R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8487–8488. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Blanco FJ, Tycko R. J. Magn. Reson. 2001;149:131–138. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Feng X, Lee YK, Sandstrom D, Eden M, Maisel H, Sebald A, Levitt MH. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996;257:314–320. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Feng X, Eden M, Brinkmann A, Luthman H, Eriksson L, Graslund A, Antzutkin ON, Levitt MH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:12006–12007. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Costa PR, Gross JD, Hong M, Griffin RG. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1997;280:95–103. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hong M, Gross JD, Griffin RG. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1997;101:5869–5874. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Reif B, Hohwy M, Jaroniec CP, Rienstra CM, Griffin RG. J. Magn. Reson. 2000;145:132–141. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ladizhansky V, Veshtort M, Griffin RG. J. Magn. Reson. 2002;154:317–324. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chan JCC, Tycko R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11828–11829. doi: 10.1021/ja0369820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Tycko R, Dabbagh G, Mirau PA. J. Magn. Reson. 1989;85:265–274. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Tycko R, Dabbagh G. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1990;173:461–465. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ishii Y, Balbach JJ, Tycko R. Chem. Phys. 2001;266:231–236. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Gullion T, Schaefer J. J. Magn. Reson. 1989;81:196–200. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Anderson RC, Gullion T, Joers JM, Shapiro M, Villhauer EB, Weber HP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:10546–10550. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Gullion T, Vega S. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1992;194:423–428. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Bennett AE, Ok JH, Griffin RG, Vega S. J. Chem. Phys. 1992;96:8624–8627. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Bennett AE, Weliky DP, Tycko R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:4897–4898. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Bennett AE, Rienstra CM, Griffiths JM, Zhen WG, Lansbury PT, Griffin RG. J. Chem. Phys. 1998;108:9463–9479. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Nomura K, Takegoshi K, Terao T, Uchida K, Kainosho M. J. Biomol. NMR. 2000;17:111–123. doi: 10.1023/a:1008398906753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Oyler NA, Tycko R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:4478–4479. doi: 10.1021/ja031719k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Wille H, Michelitsch MD, Guenebaut V, Supattapone S, Serban A, Cohen FE, Agard DA, Prusiner SB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:3563–3568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052703499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Govaerts C, Wille H, Prusiner SB, Cohen FE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:8342–8347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402254101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Guo JT, Wetzel R, Ying X. 2004;57:357–364. doi: 10.1002/prot.20222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Margittai M, Langen R. 2004;101:10278–10283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401911101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Der-Sarkissian A, Jao CC, Chen J, Langen R. 2003;278:37530–37535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Diaz-Avalos R, Long C, Fontano E, Balbirnie M, Grothe R, Eisenberg D, Caspar DLD. 2003;330:1165–1175. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00659-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Kheterpal I, Zhou S, Cook KD, Wetzel R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:13597–13601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250288897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kheterpal I, Williams A, Murphy C, Bledsoe B, Wetzel R. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11757–11767. doi: 10.1021/bi010805z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Williams AD, Portelius E, Kheterpal I, Guo JT, Cook KD, Xu Y, Wetzel R. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;335:833–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Torok M, Milton S, Kayed R, Wu P, McIntire T, Glabe CG, Langen R. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:40810–40815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205659200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Ma BY, Nussinov R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14126–14131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212206899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Jimenez JL, Nettleton EJ, Bouchard M, Robinson CV, Dobson CM, Saibil HR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:9196–9201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142459399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Jimenez JL, Guijarro JL, Orlova E, Zurdo J, Dobson CM, Sunde M, Saibil HR. Embo J. 1999;18:815–821. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.4.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Mayeux R, Tang MX, Jacobs DM, Manly J, Bell K, Merchant C, Small SA, Stern Y, Wisniewski HM, Mehta PD. Ann. Neurol. 1999;46:412–416. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199909)46:3<412::aid-ana19>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Collins SR, Douglass A, Vale RD, Weissman JS. PLOS Biology. 2004;2:1582–1590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Laws DD, Bitter HML, Liu K, Ball HL, Kaneko K, Wille H, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Pines A, Wemmer DE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:11686–11690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201404298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Goldsbury CS, Wirtz S, Muller SA, Sunderji S, Wicki P, Aebi U, Frey P. J. Struct. Biol. 2000;130:217–231. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Goldsbury C, Goldie K, Pellaud J, Seelig J, Frey P, Muller SA, Kistler J, Cooper GJS, Aebi U. J. Struct. Biol. 2000;130:352–362. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Jimenez JL, Tennent G, Pepys M, Saibil HR. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;311:241–247. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Harper JD, Lieber CM, Lansbury PT. Chem. Biol. 1997;4:951–959. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Chien P, Weissman JS. Nature. 2001;410:223–227. doi: 10.1038/35065632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Safar J, Wille H, Itrri V, Groth D, Serban H, Torchia M, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Nat. Med. 1998;4:1157–1165. doi: 10.1038/2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Telling GC, Parchi P, DeArmond SJ, Cortelli P, Montagna P, Gabizon R, Mastrianni J, Lugaresi E, Gambetti P, Prusiner SB. Science. 1996;274:2079–2082. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Bessen RA, Marsh RF. J. Virol. 1992;66:2096–2101. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2096-2101.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Tanaka M, Chien P, Naber N, Cooke R, Weissman JS. Nature. 2004;428:323–328. doi: 10.1038/nature02392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Serpell LC, Blake CCF, Fraser PE. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13269–13275. doi: 10.1021/bi000637v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Serpell LC, Smith JM. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;299:225–231. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Murakami K, Irie K, Morimoto A, Ohigashi H, Shindo M, Nagao M, Shimizu T, Shirasawa T. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2002;294:5–10. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00430-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Kheterpal I, Lashuel HA, Hartley DM, Wlaz T, Lansbury PT, Wetzel R. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14092–14098. doi: 10.1021/bi0357816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Thakur AK, Wetzel R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:17014–17019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252523899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Lakdawala AS, Morgan DM, Liotta DC, Lynn DG, Snyder JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:15150–15151. doi: 10.1021/ja0273290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Tjernberg LO, Callaway DJE, Tjernberg A, Hahne S, Lilliehook C, Terenius L, Thyberg J, Nordstedt C. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:12619–12625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Li LP, Darden TA, Bartolotti L, Kominos D, Pedersen LG. Biophys. J. 1999;76:2871–2878. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77442-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Lazo ND, Downing DT. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1731–1735. doi: 10.1021/bi971016d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Perutz MF, Finch JT, Berriman J, Lesk A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:5591–5595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042681399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Pickersgill RW. Structure. 2003;11:137–138. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Kishimoto A, Hasegawa K, Suzuki H, Taguchi H, Namba K, Yoshida M. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;315:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Emsley P, Charles IG, Fairweather NF, Isaacs NW. Nature. 1996;381:90–92. doi: 10.1038/381090a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Kamen DE, Griko Y, Woody RW. Biochemistry. 2000;39:15932–15943. doi: 10.1021/bi001900v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Koradi R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]