Abstract

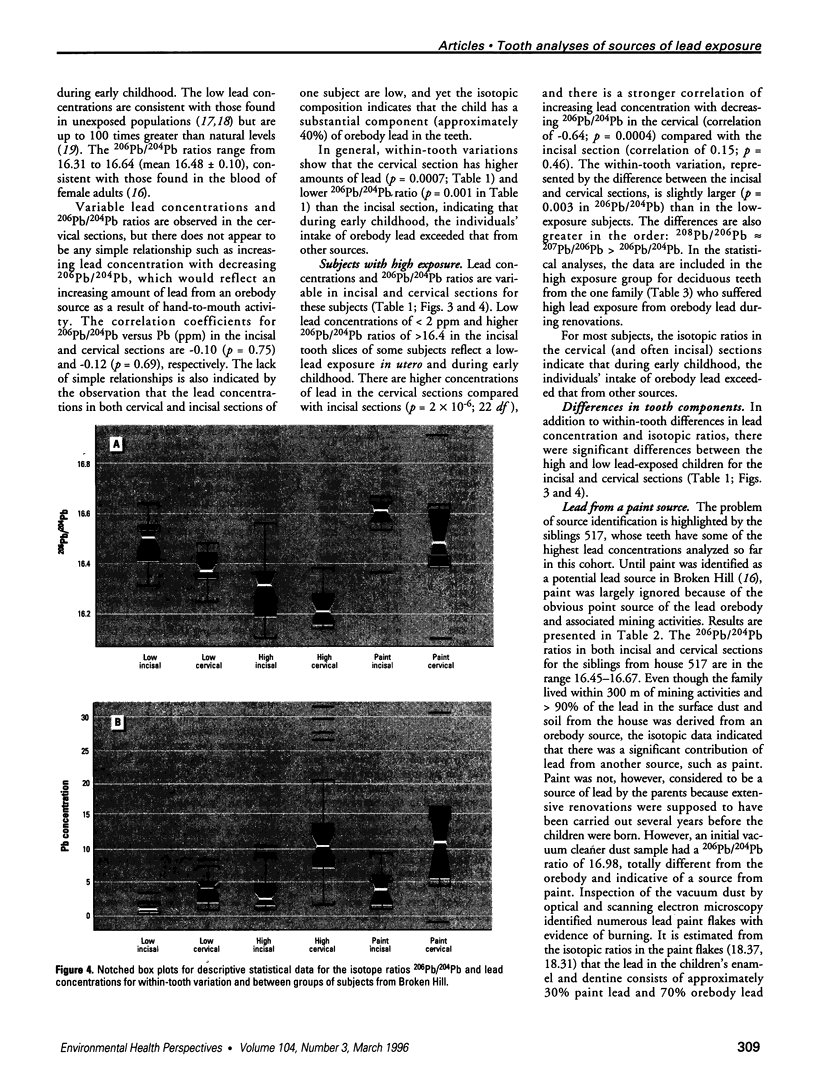

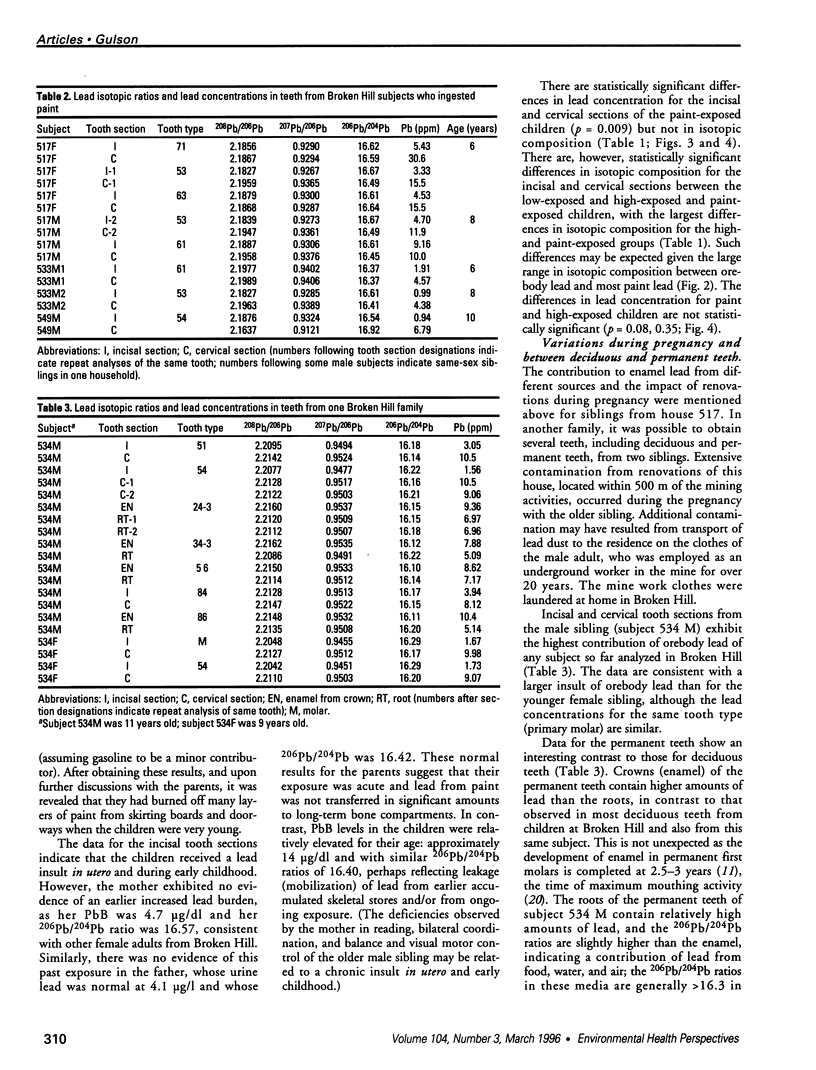

The sources and intensity of lead exposure in utero and in early childhood were determined using stable lead isotopic ratios and lead concentrations of incisal and cervical sections of deciduous teeth from 30 exposed and nonexposed children from the Broken Hill lead mining community in Australia. Incisal sections, consisting mostly of enamel, generally have low amounts of lead and isotopic compositions consistent with those expected in the mother during pregnancy. Cervical sections, consisting mostly of dentine with secondary dentine removed by resorption and reaming, generally have higher amounts of lead than the enamel and isotopic compositions consistent with the source of postnatal exposure. There are statistically significant differences in lead concentrations between incisal and cervical sections, representing within-tooth variation, for children with low and high lead exposure (p = 0.0007, 2 x 10(-6), respectively) and for those who have ingested leaded paint (p = 0.009). Statistically significant differences between incisal and cervical sections in these three exposure groups are also exhibited by the three sets of lead isotope ratios (e.g., p = 0.001 for 206Pb/204Pb ratio in the low exposure group). There are statistically significant differences between the low and high lead exposure groups for lead concentrations and isotopic ratios in incisal (p = 0.005 for lead concentration and 6 x 10(-6) for 206Pb/204Pb ratio) and cervical sections (p = 5 x 10(-5) for lead concentration and 6 x 10(-6) for 206Pb/204Pb ratio). The dentine results reflect an increased exposure to lead from the lead-zinc-silver mineral deposit (orebody lead) during early childhood, probably associated with hand-to-mouth activity. Leaded paint was identified as the source of elevated tooth lead in at least two cases. Increased exposure to lead from orebody and paint sources in utero was implicated in two cases, but there was no indication of previous exposure from the mothers' current blood leads, suggesting an acute rather than a chronic exposure for the mothers. Permanent teeth from one subject had lower amounts of lead in the roots compared with the crowns, and the isotopic composition of the crowns were consistent with the data for the deciduous teeth from the same subject. Based on changes in the isotopic composition of enamel and dentine, it is provisionally estimated that lead is added to dentine at a rate of approximately 2-3% per year.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bellinger D. C. Interpreting the literature on lead and child development: the neglected role of the "experimental system". Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1995 May-Jun;17(3):201–212. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(94)00081-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies D. J., Thornton I., Watt J. M., Culbard E. B., Harvey P. G., Delves H. T., Sherlock J. C., Smart G. A., Thomas J. F., Quinn M. J. Lead intake and blood lead in two-year-old U.K. urban children. Sci Total Environ. 1990 Jan;90:13–29. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(90)90182-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delves H. T., Clayton B. E., Carmichael A., Bubear M., Smith M. An appraisal of the analytical significance of tooth-lead measurements as possible indices of environmental exposure of children to lead. Ann Clin Biochem. 1982 Sep;19(Pt 5):329–337. doi: 10.1177/000456328201900502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P., Lyngbye T., Hansen O. N. Lead concentration in deciduous teeth: variation related to tooth type and analytical technique. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1986;19(3):437–444. doi: 10.1080/15287398609530941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulson B. L., Mahaffey K. R., Mizon K. J., Korsch M. J., Cameron M. A., Vimpani G. Contribution of tissue lead to blood lead in adult female subjects based on stable lead isotope methods. J Lab Clin Med. 1995 Jun;125(6):703–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulson B., Wilson D. History of lead exposure in children revealed from isotopic analyses of teeth. Arch Environ Health. 1994 Jul-Aug;49(4):279–283. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1994.9937480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S. R., Fremlin J. H. A study of lead distribution in human teeth, using charged particle activation analysis. Caries Res. 1974;8(3):283–292. doi: 10.1159/000260117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manea-Krichten M., Patterson C., Miller G., Settle D., Erel Y. Comparative increases of lead and barium with age in human tooth enamel, rib and ulna. Sci Total Environ. 1991 Sep;107:179–203. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(91)90259-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manton W. I. Total contribution of airborne lead to blood lead. Br J Ind Med. 1985 Mar;42(3):168–172. doi: 10.1136/oem.42.3.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson C., Ericson J., Manea-Krichten M., Shirahata H. Natural skeletal levels of lead in Homo sapiens sapiens uncontaminated by technological lead. Sci Total Environ. 1991 Sep;107:205–236. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(91)90260-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz M. B., Leviton A., Bellinger D. C. Blood lead--tooth lead relationship among Boston children. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1989 Oct;43(4):485–492. doi: 10.1007/BF01701924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz M. B., Leviton A., Bellinger D. Relationships between serial blood lead levels and exfoliated tooth dentin lead levels: models of tooth lead kinetics. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993 Nov;53(5):338–341. doi: 10.1007/BF01351840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz M. B., Wetherill G. W., Kopple J. D. Kinetic analysis of lead metabolism in healthy humans. J Clin Invest. 1976 Aug;58(2):260–270. doi: 10.1172/JCI108467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro I. M., Mitchell G., Davidson I., Katz S. H. The lead content of teeth. Evidence establishing new minimal levels of exposure in a living preindustrialized human population. Arch Environ Health. 1975 Oct;30(10):483–486. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1975.10666758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbergeld E. K., Schwartz J., Mahaffey K. Lead and osteoporosis: mobilization of lead from bone in postmenopausal women. Environ Res. 1988 Oct;47(1):79–94. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(88)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenhout A. Kinetics of lead storage in teeth and bones: an epidemiologic approach. Arch Environ Health. 1982 Jul-Aug;37(4):224–231. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1982.10667569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson G. N., Robertson E. F., Fitzgerald S. Lead mobilization during pregnancy. Med J Aust. 1985 Aug 5;143(3):131–131. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1985.tb122859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]