Abstract

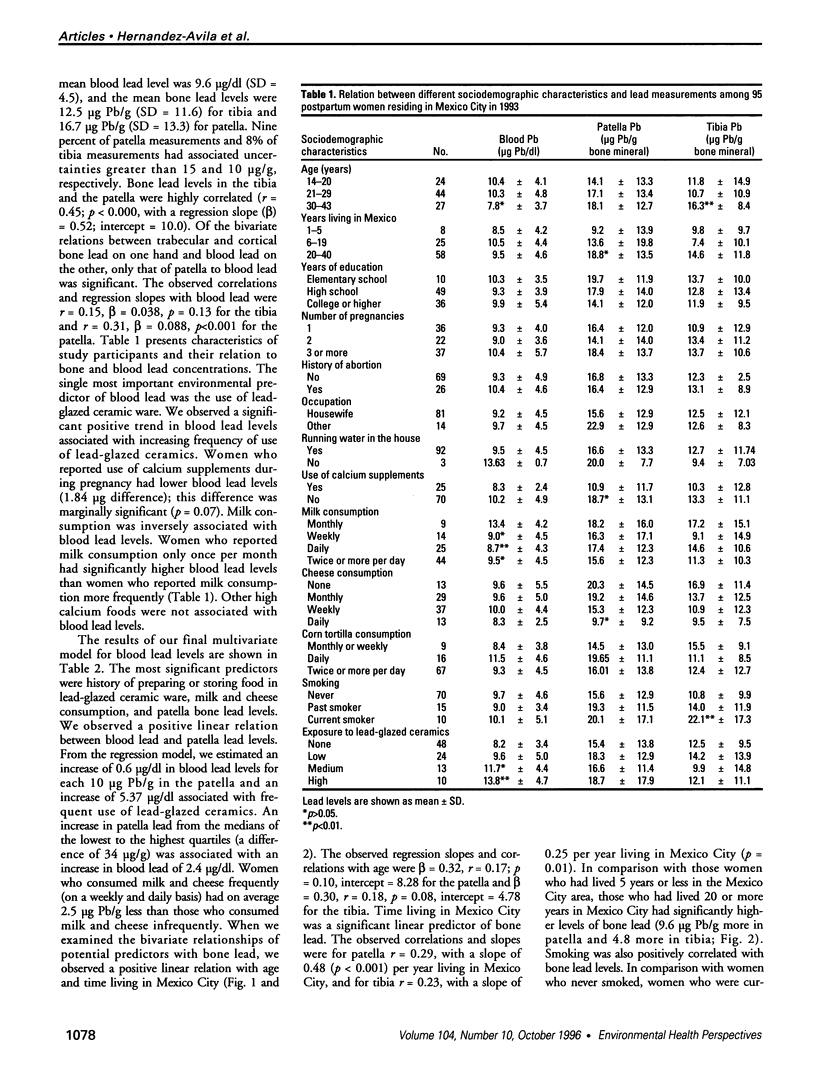

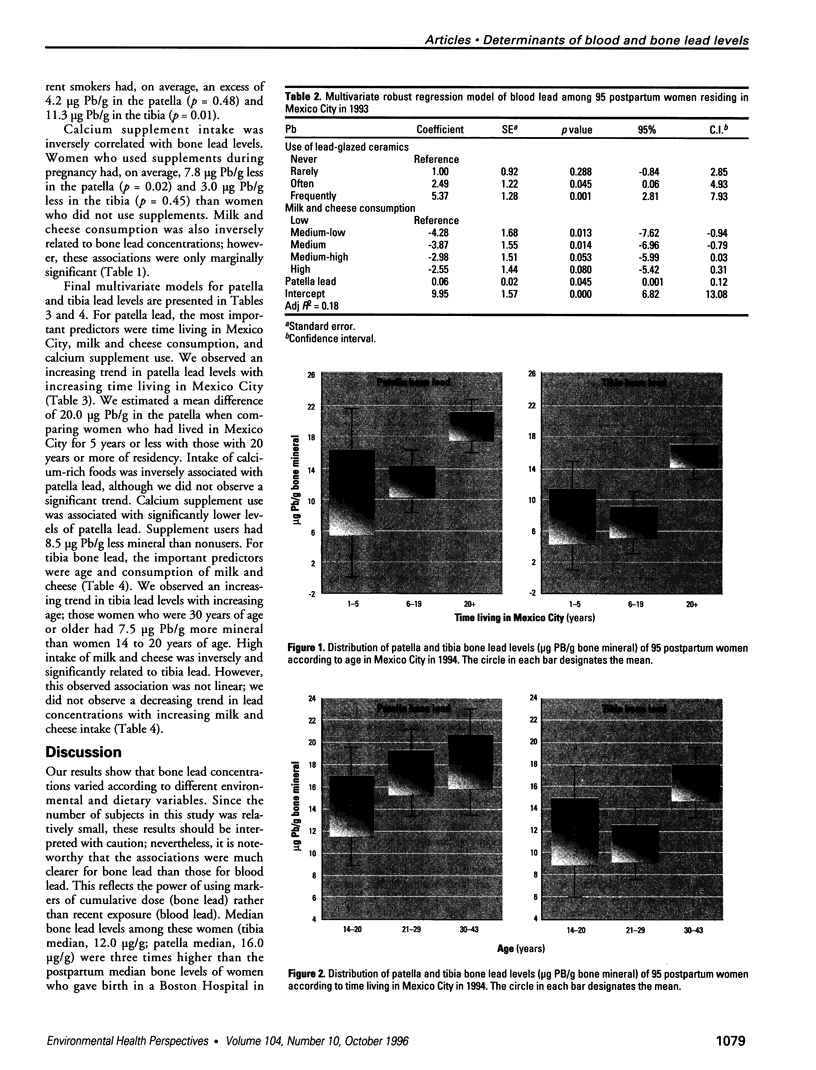

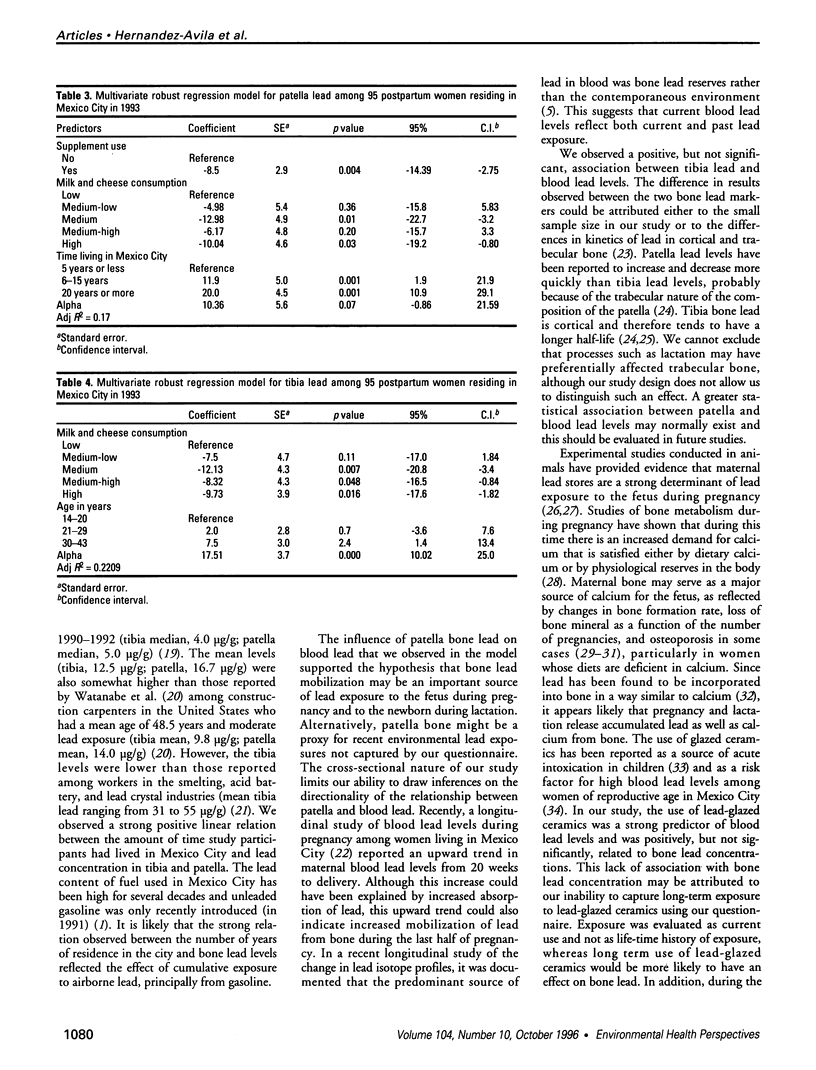

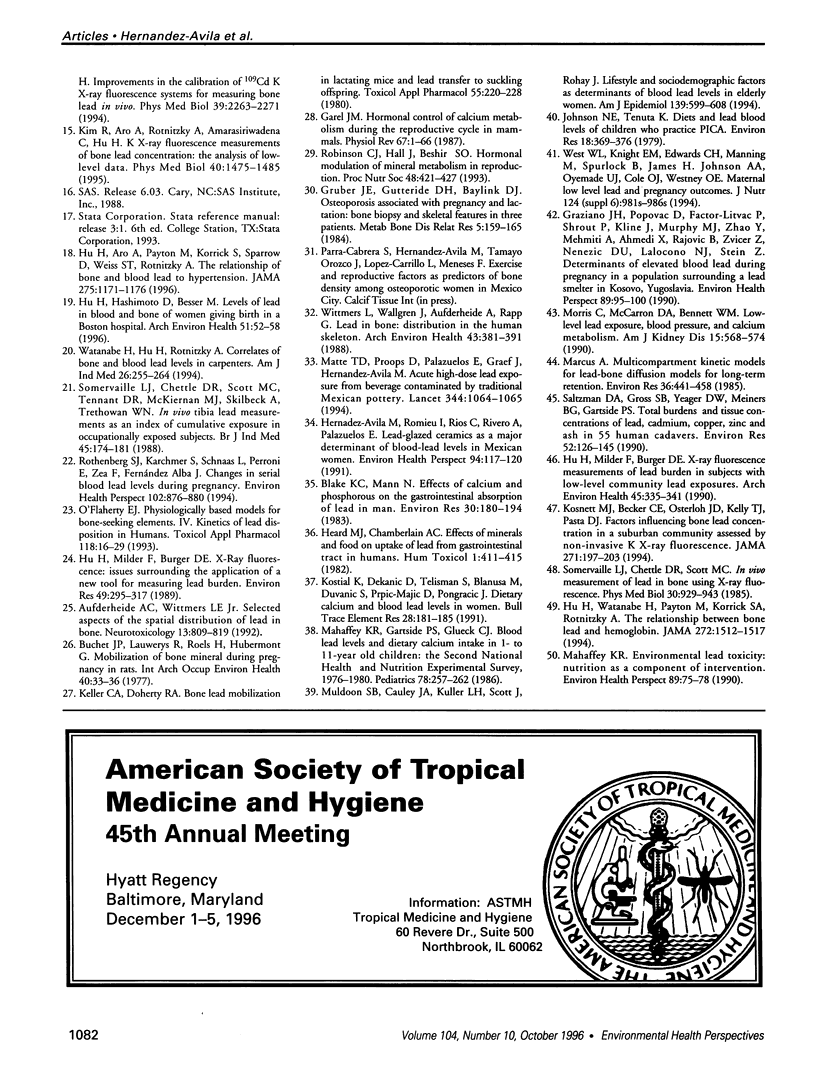

Despite the recent declines in environmental lead exposure in the United States and Mexico, the potential for delayed toxicity from bone lead stores remains a significant public health concern. Some evidence indicates that mobilization of lead from bone may be markedly enhanced during the increased bone turnover of pregnancy and lactation, resulting in lead exposure to the fetus and the breast-fed infant. We conducted a cross-sectional investigation of the interrelationships between environmental, dietary, and lifestyle histories, blood lead levels, and bone lead levels among 98 recently postpartum women living in Mexico City. Lead levels in the patella (representing trabecular bone) and tibia (representing cortical bone) were measured by K X-ray fluorescence (KXRF). Multivariate linear regression models showed that significant predictors of higher blood lead included a history of preparing or storing food in lead-glazed ceramic ware, lower milk consumption, and higher levels of lead in patella bone. A 34 micrograms/g increase in patella lead (from the medians of the lowest to the highest quartiles) was associated with an increase in blood lead of 2.4 micrograms/dl. Given the measurement error associated with KXRF and the extrapolation of lead burden from a single bone site, this contribution probably represents an underestimate of the influence of trabecular bone on blood lead. Significant predictors of bone lead in multivariate models included years living in Mexico City, lower consumption of high calcium content foods, and nonuse of calcium supplements for the patella and years living in Mexico City, older age, and lower calcium intake for tibia bone. Low consumption of milk and cheese, as compared to the highest consumption category (every day), was associated with an increase in tibia bone lead of 9.7 micrograms Pb/g bone mineral. The findings of this cross-sectional study suggest that patella bone is a significant contributor to blood lead during lactation and that consumption of high calcium content foods may protect against the accumulation of lead in bone.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aufderheide A. C., Wittmers L. E., Jr Selected aspects of the spatial distribution of lead in bone. Neurotoxicology. 1992 Winter;13(4):809–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry P. S., Mossman D. B. Lead concentrations in human tissues. Br J Ind Med. 1970 Oct;27(4):339–351. doi: 10.1136/oem.27.4.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger D., Hu H., Titlebaum L., Needleman H. L. Attentional correlates of dentin and bone lead levels in adolescents. Arch Environ Health. 1994 Mar-Apr;49(2):98–105. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1994.9937461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake K. C., Mann M. Effect of calcium and phosphorus on the gastrointestinal absorption of 203Pb in man. Environ Res. 1983 Feb;30(1):188–194. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(83)90179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchet J. P., Lauwerys R., Roels H., Hubermont G. Mobilization of lead during pregnancy in rats. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1977 Oct 17;40(1):33–36. doi: 10.1007/BF00435515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersson J. O., Ahlgren L., Schütz A., Skerfving S., Mattsson S. Decrease of skeletal lead levels in man after end of occupational exposure. Arch Environ Health. 1986 Sep-Oct;41(5):312–318. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1986.9936703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garel J. M. Hormonal control of calcium metabolism during the reproductive cycle in mammals. Physiol Rev. 1987 Jan;67(1):1–66. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1987.67.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano J. H., Popovac D., Factor-Litvak P., Shrout P., Kline J., Murphy M. J., Zhao Y. H., Mehmeti A., Ahmedi X., Rajovic B. Determinants of elevated blood lead during pregnancy in a population surrounding a lead smelter in Kosovo, Yugoslavia. Environ Health Perspect. 1990 Nov;89:95–100. doi: 10.1289/ehp.908995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber H. E., Gutteridge D. H., Baylink D. J. Osteoporosis associated with pregnancy and lactation: bone biopsy and skeletal features in three patients. Metab Bone Dis Relat Res. 1984;5(4):159–165. doi: 10.1016/0221-8747(84)90023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulson B. L., Mahaffey K. R., Mizon K. J., Korsch M. J., Cameron M. A., Vimpani G. Contribution of tissue lead to blood lead in adult female subjects based on stable lead isotope methods. J Lab Clin Med. 1995 Jun;125(6):703–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heard M. J., Chamberlain A. C. Effect of minerals and food on uptake of lead from the gastrointestinal tract in humans. Hum Toxicol. 1982 Oct;1(4):411–415. doi: 10.1177/096032718200100407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez Avila M., Romieu I., Rios C., Rivero A., Palazuelos E. Lead-glazed ceramics as major determinants of blood lead levels in Mexican women. Environ Health Perspect. 1991 Aug;94:117–120. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94-1567967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H., Aro A., Payton M., Korrick S., Sparrow D., Weiss S. T., Rotnitzky A. The relationship of bone and blood lead to hypertension. The Normative Aging Study. JAMA. 1996 Apr 17;275(15):1171–1176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H., Aro A., Rotnitzky A. Bone lead measured by X-ray fluorescence: epidemiologic methods. Environ Health Perspect. 1995 Feb;103 (Suppl 1):105–110. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H., Hashimoto D., Besser M. Levels of lead in blood and bone of women giving birth in a Boston hospital. Arch Environ Health. 1996 Jan-Feb;51(1):52–58. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1996.9935994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H., Milder F. L., Burger D. E. X-ray fluorescence measurements of lead burden in subjects with low-level community lead exposure. Arch Environ Health. 1990 Nov-Dec;45(6):335–341. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1990.10118752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H., Milder F. L., Burger D. E. X-ray fluorescence: issues surrounding the application of a new tool for measuring burden of lead. Environ Res. 1989 Aug;49(2):295–317. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(89)80074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H., Watanabe H., Payton M., Korrick S., Rotnitzky A. The relationship between bone lead and hemoglobin. JAMA. 1994 Nov 16;272(19):1512–1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N. E., Tenuta K. Diets and lead blood levels of children who practice pica. Environ Res. 1979 Apr;18(2):369–376. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(79)90113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C. A., Doherty R. A. Bone lead mobilization in lactating mice and lead transfer to suckling offspring. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1980 Sep 15;55(2):220–228. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(80)90083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim R., Aro A., Rotnitzky A., Amarasiriwardena C., Hu H. K x-ray fluorescence measurements of bone lead concentration: the analysis of low-level data. Phys Med Biol. 1995 Sep;40(9):1475–1485. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/40/9/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosnett M. J., Becker C. E., Osterloh J. D., Kelly T. J., Pasta D. J. Factors influencing bone lead concentration in a suburban community assessed by noninvasive K x-ray fluorescence. JAMA. 1994 Jan 19;271(3):197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostial K., Dekanić D., Telisman S., Blanusa M., Duvancić S., Prpić-Majić D., Pongracić J. Dietary calcium and blood lead levels in women. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1991 Mar;28(3):181–185. doi: 10.1007/BF02990465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahaffey K. R. Environmental lead toxicity: nutrition as a component of intervention. Environ Health Perspect. 1990 Nov;89:75–78. doi: 10.1289/ehp.908975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahaffey K. R., Gartside P. S., Glueck C. J. Blood lead levels and dietary calcium intake in 1- to 11-year-old children: the Second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1976 to 1980. Pediatrics. 1986 Aug;78(2):257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus A. H. Multicompartment kinetic models for lead. I. Bone diffusion models for long-term retention. Environ Res. 1985 Apr;36(2):441–458. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(85)90037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matte T. D., Proops D., Palazuelos E., Graef J., Hernandez Avila M. Acute high-dose lead exposure from beverage contaminated by traditional Mexican pottery. Lancet. 1994 Oct 15;344(8929):1064–1065. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91715-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris C., McCarron D. A., Bennett W. M. Low-level lead exposure, blood pressure, and calcium metabolism. Am J Kidney Dis. 1990 Jun;15(6):568–574. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon S. B., Cauley J. A., Kuller L. H., Scott J., Rohay J. Lifestyle and sociodemographic factors as determinants of blood lead levels in elderly women. Am J Epidemiol. 1994 Mar 15;139(6):599–608. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman H. L., Schell A., Bellinger D., Leviton A., Allred E. N. The long-term effects of exposure to low doses of lead in childhood. An 11-year follow-up report. N Engl J Med. 1990 Jan 11;322(2):83–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199001113220203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Flaherty E. J. Physiologically based models for bone-seeking elements. IV. Kinetics of lead disposition in humans. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1993 Jan;118(1):16–29. doi: 10.1006/taap.1993.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romieu I., Palazuelos E., Hernandez Avila M., Rios C., Muñoz I., Jimenez C., Cahero G. Sources of lead exposure in Mexico City. Environ Health Perspect. 1994 Apr;102(4):384–389. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg S. J., Karchmer S., Schnaas L., Perroni E., Zea F., Fernández Alba J. Changes in serial blood lead levels during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 1994 Oct;102(10):876–880. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman B. E., Gross S. B., Yeager D. W., Meiners B. G., Gartside P. S. Total body burdens and tissue concentrations of lead, cadmium, copper, zinc, and ash in 55 human cadavers. Environ Res. 1990 Aug;52(2):126–145. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(05)80248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J. Low-level lead exposure and children's IQ: a meta-analysis and search for a threshold. Environ Res. 1994 Apr;65(1):42–55. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1994.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbergeld E. K. Lead in bone: implications for toxicology during pregnancy and lactation. Environ Health Perspect. 1991 Feb;91:63–70. doi: 10.1289/ehp.919163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somervaille L. J., Chettle D. R., Scott M. C. In vivo measurement of lead in bone using x-ray fluorescence. Phys Med Biol. 1985 Sep;30(9):929–943. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/30/9/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somervaille L. J., Chettle D. R., Scott M. C., Tennant D. R., McKiernan M. J., Skilbeck A., Trethowan W. N. In vivo tibia lead measurements as an index of cumulative exposure in occupationally exposed subjects. Br J Ind Med. 1988 Mar;45(3):174–181. doi: 10.1136/oem.45.3.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenhout A. Kinetics of lead storage in teeth and bones: an epidemiologic approach. Arch Environ Health. 1982 Jul-Aug;37(4):224–231. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1982.10667569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern M. P., Gonzalez C., Hernandex M., Knapp J. A., Hazuda H. P., Villapando E., Valdez R. A., Haffner S. M., Mitchell B. D. Performance of semiquantitative food frequency questionnaires in international comparisons. Mexico City versus San Antonio, Texas. Ann Epidemiol. 1993 May;3(3):300–307. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H., Hu H., Rotnitzky A. Correlates of bone and blood lead levels in carpenters. Am J Ind Med. 1994 Aug;26(2):255–264. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700260211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West W. L., Knight E. M., Edwards C. H., Manning M., Spurlock B., James H., Johnson A. A., Oyemade U. J., Cole O. J., Westney O. E. Maternal low level lead and pregnancy outcomes. J Nutr. 1994 Jun;124(6 Suppl):981S–986S. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.suppl_6.981S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett W. C., Sampson L., Stampfer M. J., Rosner B., Bain C., Witschi J., Hennekens C. H., Speizer F. E. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1985 Jul;122(1):51–65. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmers L. E., Jr, Aufderheide A. C., Wallgren J., Rapp G., Jr, Alich A. Lead in bone. IV. Distribution of lead in the human skeleton. Arch Environ Health. 1988 Nov-Dec;43(6):381–391. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1988.9935855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]