Abstract

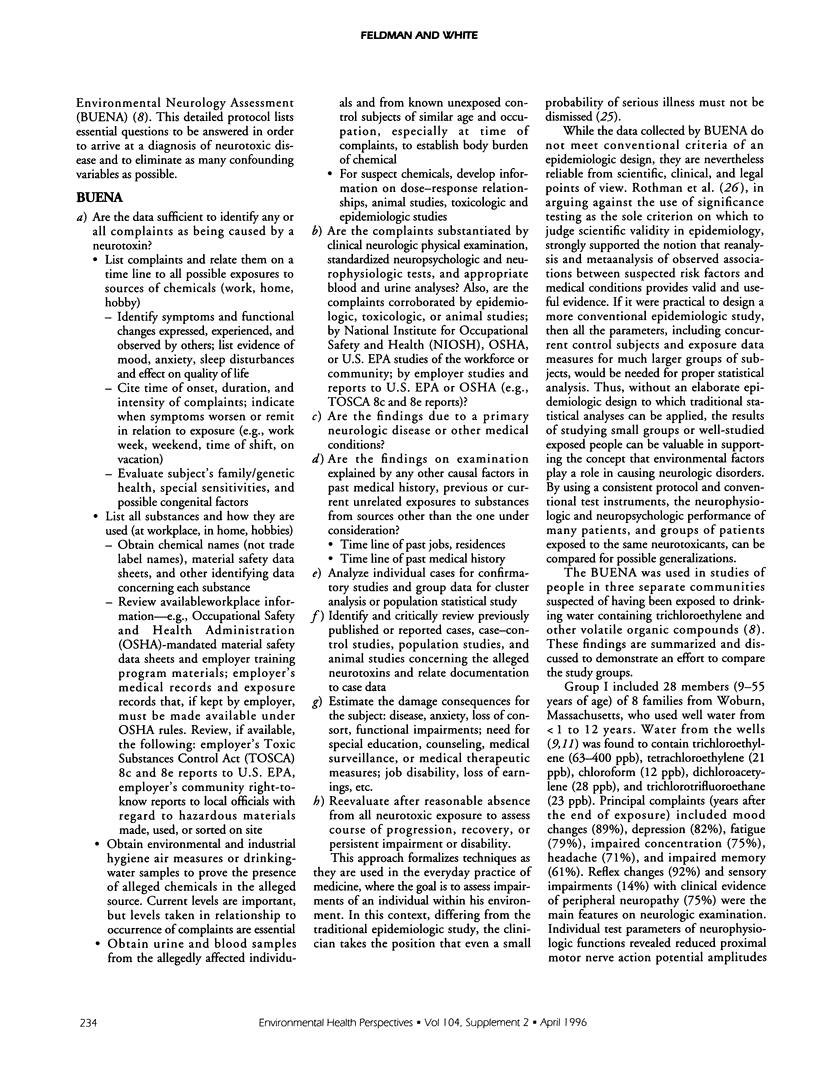

This review describes strategies used by a clinical neurologist in the investigation of neurotoxic disease. It emphasizes the need for a high level of suspicion that environmental substances are capable of producing impairments in neurologic and neurobehavioral functions. Because of the difficulties in differentiating neurotoxic from nonneurotoxic disease when presented with common neurological symptoms, it is necessary to rely upon corroborative evidence from past medical records, work and environmental histories, and exposure data, as well as detailed neurological examinations, to reach a conclusion about causation. Sensitive electrophysiologic and neuropsychologic test batteries are useful in identifying subclinical impairments and in providing objective confirmation of abnormalities in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Combining scientific and epidemiologic information with experience and clinical judgment, these sources of information are used in the formulation of a clinical diagnosis. When many patients among a group of people are exposed to neurotoxicants, the effects of the exposure may vary from one to another because of differences in susceptibility, duration of exposure and dosage of neurotoxicant, and other possible risk factors. Group statistics may obscure a significant effect for the larger group, despite clinically obvious effects in an individual. The neurologist applies clinical skills and refers to the accumulated neurotoxicologic literature as a frame of reference to make a diagnosis about an individual patient or a group of patients who have been exposed to particular neurotoxicants. The Boston University Environmental Neurology Assessment (BUENA) is a scheme that attempts to combine epidemiologic methodology and clinical approaches to detect effects of neurotoxic exposure. The advantages and limitations of such a strategy are discussed.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Buffler P. A., Crane M., Key M. M. Possibilities of detecting health effects by studies of populations exposed to chemicals from waste disposal sites. Environ Health Perspect. 1985 Oct;62:423–456. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8562423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R. G., Chirico-Post J., Proctor S. P. Blink reflex latency after exposure to trichloroethylene in well water. Arch Environ Health. 1988 Mar-Apr;43(2):143–148. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1988.9935843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R. G., Niles C. A., Kelly-Hayes M., Sax D. S., Dixon W. J., Thompson D. J., Landau E. Peripheral neuropathy in arsenic smelter workers. Neurology. 1979 Jul;29(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.29.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson L. R., Temkin N. R., Fujimoto W. Y., Stolov W. C. Effect of statistical methodology on normal limits in nerve conduction studies. Muscle Nerve. 1991 Nov;14(11):1084–1090. doi: 10.1002/mus.880141108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppäläinen A. M., Antti-Poika M. Time course of electrophysiological findings for patients with solvent poisoning. A descriptive study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1983 Feb;9(1):15–24. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]