Abstract

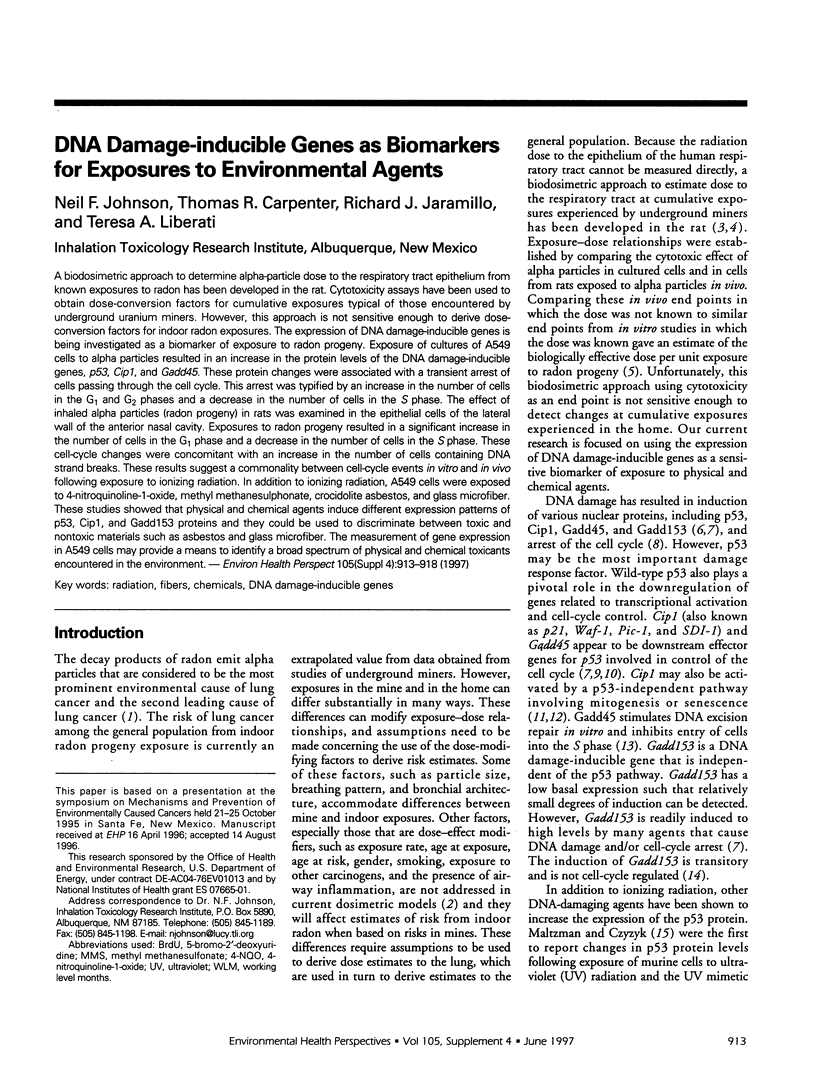

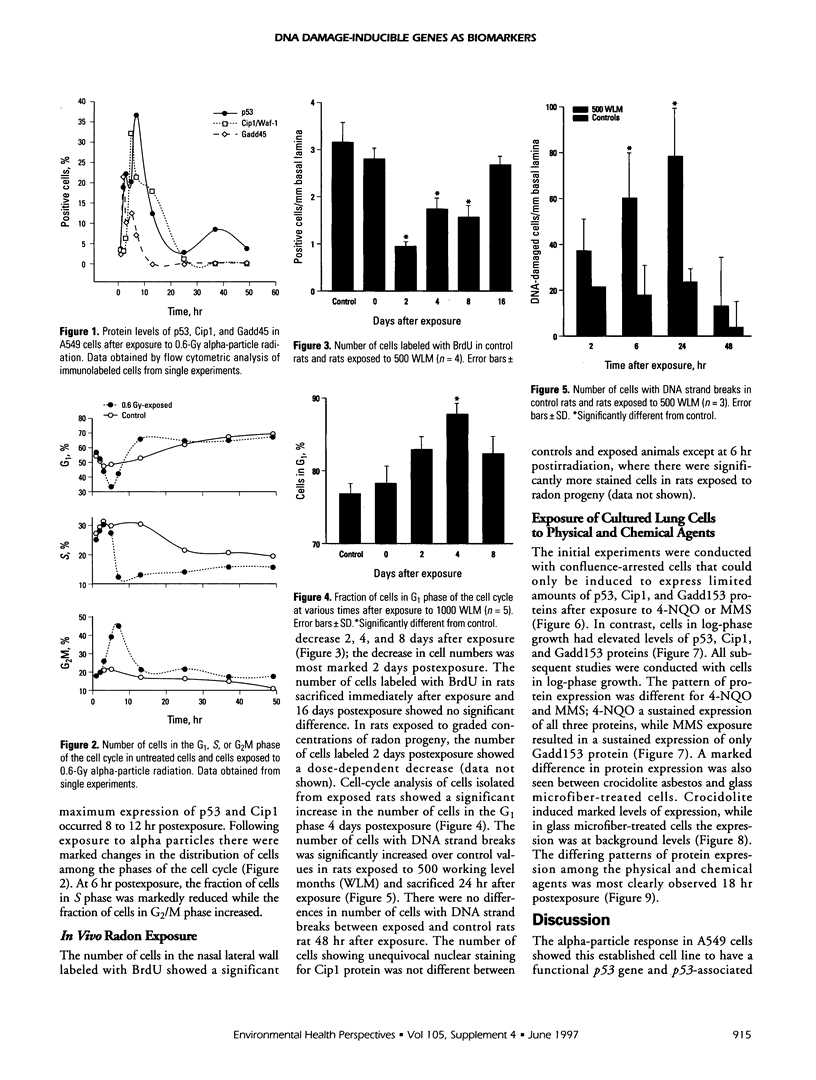

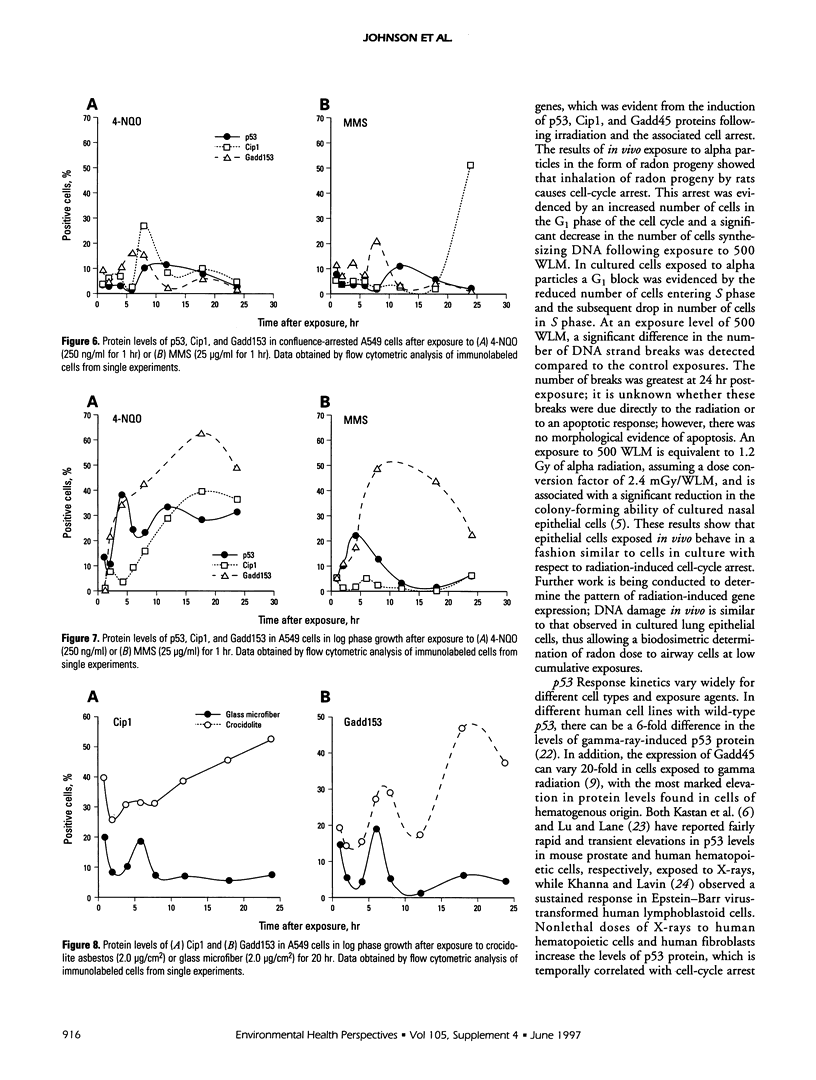

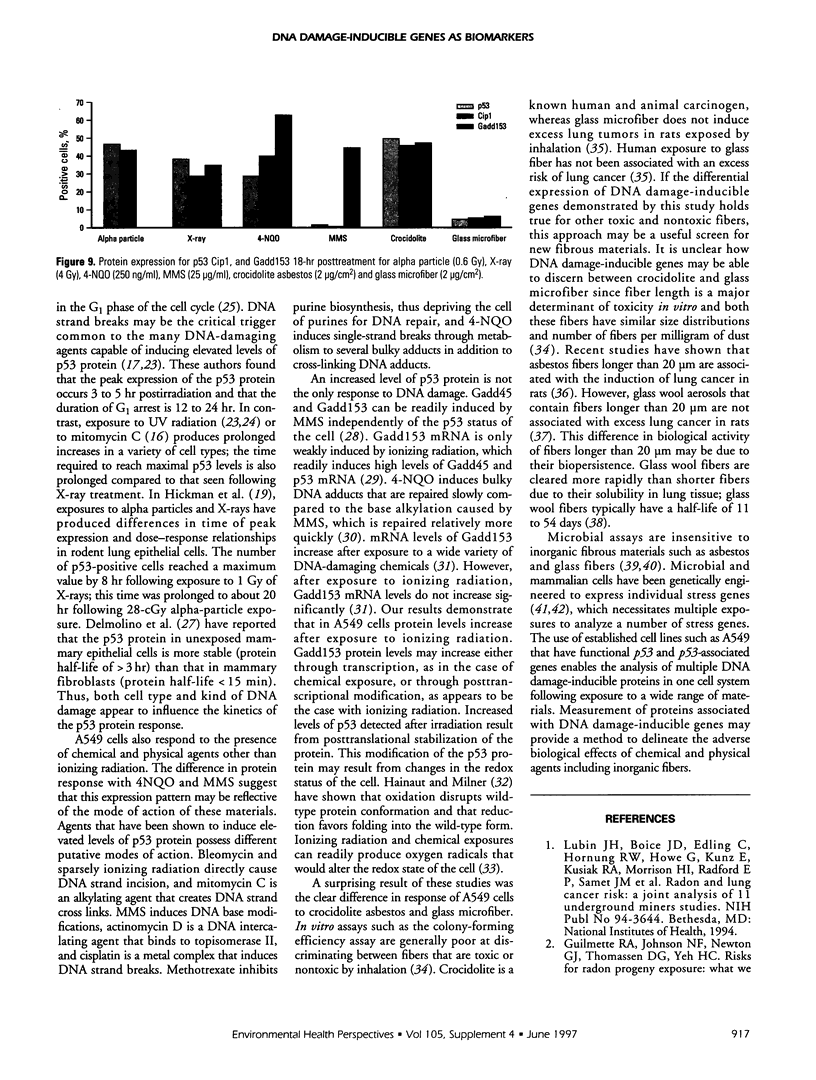

A biodosimetric approach to determine alpha-particle dose to the respiratory tract epithelium from known exposures to radon has been developed in the rat. Cytotoxicity assays have been used to obtain dose-conversion factors for cumulative exposures typical of those encountered by underground uranium miners. However, this approach is not sensitive enough to derive dose-conversion factors for indoor radon exposures. The expression of DNA damage-inducible genes is being investigated as a biomarker of exposure to radon progeny. Exposure of cultures of A549 cells to alpha particles resulted in an increase in the protein levels of the DNA damage-inducible genes, p53, Cip1, and Gadd45. These protein changes were associated with a transient arrest of cells passing through the cell cycle. This arrest was typified by an increase in the number of cells in the G1 and G2 phases and a decrease in the number of cells in the S phase. The effect of inhaled alpha particles (radon progeny) in rats was examined in the epithelial cells of the lateral well of the anterior nasal cavity. Exposures to radon progeny resulted in a significant increase in the number of cells in the G1 phase and a decrease in the number of cells in the S phase. These cell-cycle changes were concomitant with an increase in the number of cells containing DNA strand breaks. These results suggest a commonality between cell-cycle events in vitro and in vivo following exposure to ionizing radiation. In addition to ionizing radiation, A549 cells were exposed to 4-nitroquinoline-1-oxide, methyl methanesulphonate, crocidolite asbestos, and glass microfiber. These studies showed that physical and chemical agents induce different expression patterns of p53, Cip1, and Gadd153 proteins and they could be used to discriminate between toxic and nontoxic materials such as asbestos and glass microfiber. The measurement of gene expression in A549 cells may provide a means to identify a broad spectrum of physical and chemical toxicants encountered in the environment.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Berman D. W., Crump K. S., Chatfield E. J., Davis J. M., Jones A. D. The sizes, shapes, and mineralogy of asbestos structures that induce lung tumors or mesothelioma in AF/HAN rats following inhalation. Risk Anal. 1995 Apr;15(2):181–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1995.tb00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain M., Tarmy E. M. Asbestos and glass fibres in bacterial mutation tests. Mutat Res. 1977 May;43(2):159–164. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(77)90001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmolino L., Band H., Band V. Expression and stability of p53 protein in normal human mammary epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis. 1993 May;14(5):827–832. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.5.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornace A. J., Jr, Nebert D. W., Hollander M. C., Luethy J. D., Papathanasiou M., Fargnoli J., Holbrook N. J. Mammalian genes coordinately regulated by growth arrest signals and DNA-damaging agents. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Oct;9(10):4196–4203. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.10.4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsche M., Haessler C., Brandner G. Induction of nuclear accumulation of the tumor-suppressor protein p53 by DNA-damaging agents. Oncogene. 1993 Feb;8(2):307–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gately D. P., Jones J. A., Christen R., Barton R. M., Los G., Howell S. B. Induction of the growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene GADD153 by cisplatin in vitro and in vivo. Br J Cancer. 1994 Dec;70(6):1102–1106. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilmette R. A., Johnson N. F., Newton G. J., Thomassen D. G., Yeh H. C. Risks from radon progeny exposure: what we know, and what we need to know. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1991;31:569–601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.31.040191.003033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainaut P., Milner J. Redox modulation of p53 conformation and sequence-specific DNA binding in vitro. Cancer Res. 1993 Oct 1;53(19):4469–4473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall P. A., McKee P. H., Menage H. D., Dover R., Lane D. P. High levels of p53 protein in UV-irradiated normal human skin. Oncogene. 1993 Jan;8(1):203–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesterberg T. W., Miiller W. C., McConnell E. E., Chevalier J., Hadley J. G., Bernstein D. M., Thevenaz P., Anderson R. Chronic inhalation toxicity of size-separated glass fibers in Fischer 344 rats. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1993 May;20(4):464–476. doi: 10.1006/faat.1993.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman A. W., Jaramillo R. J., Lechner J. F., Johnson N. F. Alpha-particle-induced p53 protein expression in a rat lung epithelial cell strain. Cancer Res. 1994 Nov 15;54(22):5797–5800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M., Dimitrov D., Vojta P. J., Barrett J. C., Noda A., Pereira-Smith O. M., Smith J. R. Evidence for a p53-independent pathway for upregulation of SDI1/CIP1/WAF1/p21 RNA in human cells. Mol Carcinog. 1994 Oct;11(2):59–64. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940110202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N. F., Hoover M. D., Thomassen D. G., Cheng Y. S., Dalley A., Brooks A. L. In vitro activity of silicon carbide whiskers in comparison to other industrial fibers using four cell culture systems. Am J Ind Med. 1992;21(6):807–823. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700210604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N. F., Hotchkiss J. A., Harkema J. R., Henderson R. F. Proliferative responses of rat nasal epithelia to ozone. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1990 Mar 15;103(1):143–155. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(90)90270-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N. F., Newton G. J. Estimation of the dose of radon progeny to the peripheral lung and the effect of exposure to radon progeny on the alveolar macrophage. Radiat Res. 1994 Aug;139(2):163–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastan M. B., Onyekwere O., Sidransky D., Vogelstein B., Craig R. W. Participation of p53 protein in the cellular response to DNA damage. Cancer Res. 1991 Dec 1;51(23 Pt 1):6304–6311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastan M. B., Zhan Q., el-Deiry W. S., Carrier F., Jacks T., Walsh W. V., Plunkett B. S., Vogelstein B., Fornace A. J., Jr A mammalian cell cycle checkpoint pathway utilizing p53 and GADD45 is defective in ataxia-telangiectasia. Cell. 1992 Nov 13;71(4):587–597. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna K. K., Lavin M. F. Ionizing radiation and UV induction of p53 protein by different pathways in ataxia-telangiectasia cells. Oncogene. 1993 Dec;8(12):3307–3312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuerbitz S. J., Plunkett B. S., Walsh W. V., Kastan M. B. Wild-type p53 is a cell cycle checkpoint determinant following irradiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Aug 15;89(16):7491–7495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., Lane D. P. Differential induction of transcriptionally active p53 following UV or ionizing radiation: defects in chromosome instability syndromes? Cell. 1993 Nov 19;75(4):765–778. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90496-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luethy J. D., Holbrook N. J. Activation of the gadd153 promoter by genotoxic agents: a rapid and specific response to DNA damage. Cancer Res. 1992 Jan 1;52(1):5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltzman W., Czyzyk L. UV irradiation stimulates levels of p53 cellular tumor antigen in nontransformed mouse cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Sep;4(9):1689–1694. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.9.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlwrath A. J., Vasey P. A., Ross G. M., Brown R. Cell cycle arrests and radiosensitivity of human tumor cell lines: dependence on wild-type p53 for radiosensitivity. Cancer Res. 1994 Jul 15;54(14):3718–3722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michieli P., Chedid M., Lin D., Pierce J. H., Mercer W. E., Givol D. Induction of WAF1/CIP1 by a p53-independent pathway. Cancer Res. 1994 Jul 1;54(13):3391–3395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson W. G., Kastan M. B. DNA strand breaks: the DNA template alterations that trigger p53-dependent DNA damage response pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 1994 Mar;14(3):1815–1823. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. T. Cell line A549: a model system for the study of alveolar type II cell function. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977 Feb;115(2):285–293. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1977.115.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. L., Chen I. T., Zhan Q., Bae I., Chen C. Y., Gilmer T. M., Kastan M. B., O'Connor P. M., Fornace A. J., Jr Interaction of the p53-regulated protein Gadd45 with proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Science. 1994 Nov 25;266(5189):1376–1380. doi: 10.1126/science.7973727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtman E. R., Oliver C. N. Metal-catalyzed oxidation of proteins. Physiological consequences. J Biol Chem. 1991 Feb 5;266(4):2005–2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd M. D., Lee M. J., Williams J. L., Nalezny J. M., Gee P., Benjamin M. B., Farr S. B. The CAT-Tox (L) assay: a sensitive and specific measure of stress-induced transcription in transformed human liver cells. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1995 Nov;28(1):118–128. doi: 10.1006/faat.1995.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace S. S. DNA damages processed by base excision repair: biological consequences. Int J Radiat Biol. 1994 Nov;66(5):579–589. doi: 10.1080/09553009414551661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisburger J. H., Williams G. M. Carcinogen testing: current problems and new approaches. Science. 1981 Oct 23;214(4519):401–407. doi: 10.1126/science.7291981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y., Zhang H., Beach D. D type cyclins associate with multiple protein kinases and the DNA replication and repair factor PCNA. Cell. 1992 Oct 30;71(3):505–514. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90518-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Q., Bae I., Kastan M. B., Fornace A. J., Jr The p53-dependent gamma-ray response of GADD45. Cancer Res. 1994 May 15;54(10):2755–2760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Q., Carrier F., Fornace A. J., Jr Induction of cellular p53 activity by DNA-damaging agents and growth arrest. Mol Cell Biol. 1993 Jul;13(7):4242–4250. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Q., Lord K. A., Alamo I., Jr, Hollander M. C., Carrier F., Ron D., Kohn K. W., Hoffman B., Liebermann D. A., Fornace A. J., Jr The gadd and MyD genes define a novel set of mammalian genes encoding acidic proteins that synergistically suppress cell growth. Mol Cell Biol. 1994 Apr;14(4):2361–2371. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]