Abstract

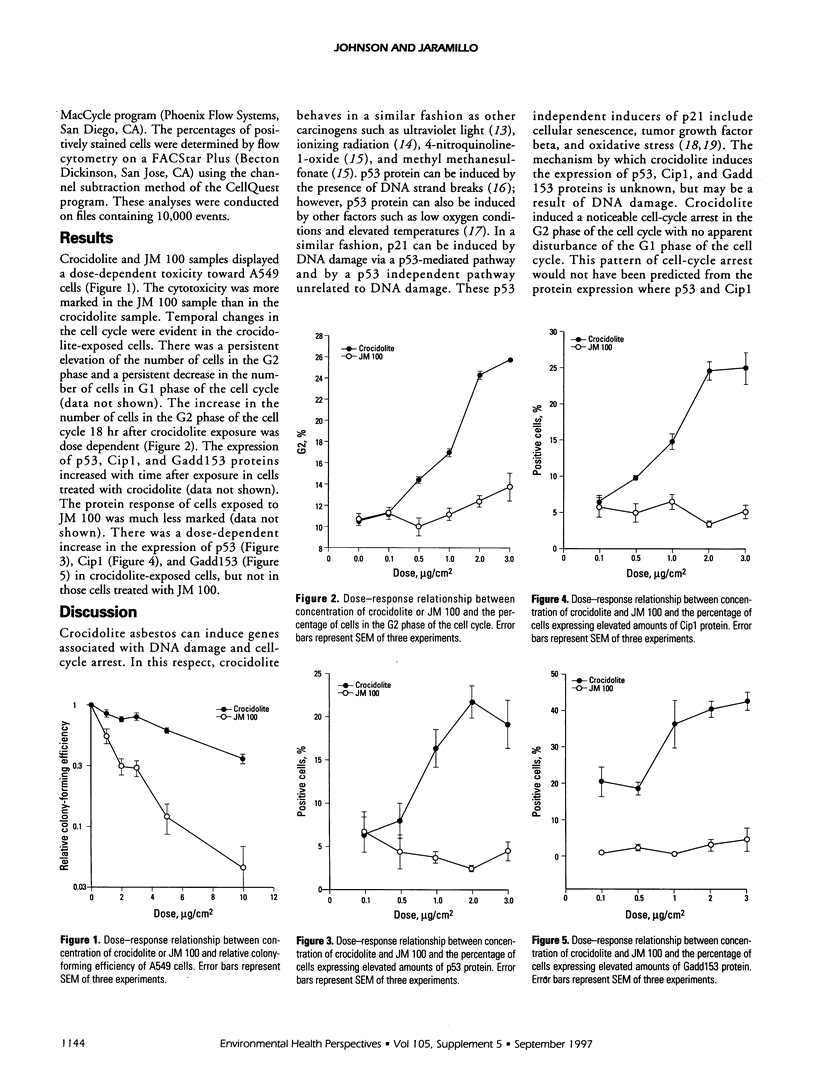

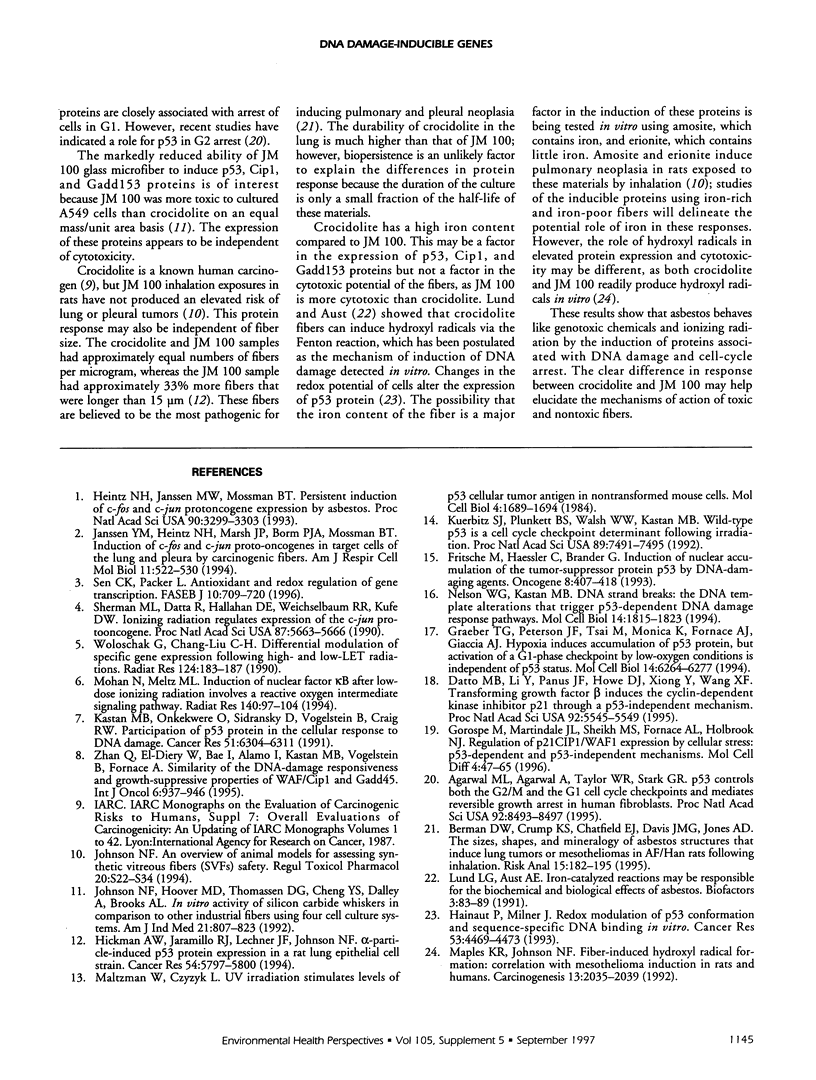

DNA damage induced by chemicals and ionizing radiation is associated with the expression of negative regulators of the cell cycle. The arrest of cells in G1 and G2 phases of the cell cycle provides time for DNA repair. Asbestos fibers are carcinogenic when inhaled by both humans and animals; however, the mechanism by which the fibers exert their effect is unknown. This work was undertaken to determine whether the expression of DNA damage-inducible genes differs between crocidolite, a fiber positive for lung tumors, and JM 100 glass microfiber, which is negative for lung tumors when inhaled by rats. Temporal and dose-related expressions of p53, Cip1, and Gadd153 proteins were determined in cultured A549 cells treated with either Union Internationale Contre le Cancer crocidolite or JM 100 for 20 hr and cultured in fresh media. Immunolabeled cells were analyzed by flow cytometry, and the increased number of protein-expressing cells was determined by subtracting the expression in unexposed cells from exposed cells. Crocidolite induced the expression of all three proteins with a maximum expression after approximately 18 hr in fresh media. At a similar time point, JM 100 did not markedly induce the three proteins. Crocidolite also induced a dose-dependent increase in the number of cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle. These results show that asbestos behaves like ionizing radiation and genotoxic chemicals by inducing proteins associated with DNA damage and cell-cycle arrest. The clear difference in response between crocidolite and JM 100 may help elucidate the mechanism of action of toxic and nontoxic fibers.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Agarwal M. L., Agarwal A., Taylor W. R., Stark G. R. p53 controls both the G2/M and the G1 cell cycle checkpoints and mediates reversible growth arrest in human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Aug 29;92(18):8493–8497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman D. W., Crump K. S., Chatfield E. J., Davis J. M., Jones A. D. The sizes, shapes, and mineralogy of asbestos structures that induce lung tumors or mesothelioma in AF/HAN rats following inhalation. Risk Anal. 1995 Apr;15(2):181–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1995.tb00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datto M. B., Li Y., Panus J. F., Howe D. J., Xiong Y., Wang X. F. Transforming growth factor beta induces the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 through a p53-independent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Jun 6;92(12):5545–5549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeber T. G., Peterson J. F., Tsai M., Monica K., Fornace A. J., Jr, Giaccia A. J. Hypoxia induces accumulation of p53 protein, but activation of a G1-phase checkpoint by low-oxygen conditions is independent of p53 status. Mol Cell Biol. 1994 Sep;14(9):6264–6277. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainaut P., Milner J. Redox modulation of p53 conformation and sequence-specific DNA binding in vitro. Cancer Res. 1993 Oct 1;53(19):4469–4473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintz N. H., Janssen Y. M., Mossman B. T. Persistent induction of c-fos and c-jun expression by asbestos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Apr 15;90(8):3299–3303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman A. W., Jaramillo R. J., Lechner J. F., Johnson N. F. Alpha-particle-induced p53 protein expression in a rat lung epithelial cell strain. Cancer Res. 1994 Nov 15;54(22):5797–5800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen Y. M., Heintz N. H., Marsh J. P., Borm P. J., Mossman B. T. Induction of c-fos and c-jun proto-oncogenes in target cells of the lung and pleura by carcinogenic fibers. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994 Nov;11(5):522–530. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.11.5.7946382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N. F., Hoover M. D., Thomassen D. G., Cheng Y. S., Dalley A., Brooks A. L. In vitro activity of silicon carbide whiskers in comparison to other industrial fibers using four cell culture systems. Am J Ind Med. 1992;21(6):807–823. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700210604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastan M. B., Onyekwere O., Sidransky D., Vogelstein B., Craig R. W. Participation of p53 protein in the cellular response to DNA damage. Cancer Res. 1991 Dec 1;51(23 Pt 1):6304–6311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuerbitz S. J., Plunkett B. S., Walsh W. V., Kastan M. B. Wild-type p53 is a cell cycle checkpoint determinant following irradiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Aug 15;89(16):7491–7495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund L. G., Aust A. E. Iron-catalyzed reactions may be responsible for the biochemical and biological effects of asbestos. Biofactors. 1991 Jun;3(2):83–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltzman W., Czyzyk L. UV irradiation stimulates levels of p53 cellular tumor antigen in nontransformed mouse cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Sep;4(9):1689–1694. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.9.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maples K. R., Johnson N. F. Fiber-induced hydroxyl radical formation: correlation with mesothelioma induction in rats and humans. Carcinogenesis. 1992 Nov;13(11):2035–2039. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.11.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell E. E. Synthetic vitreous fibers--inhalation studies. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1994 Dec;20(3 Pt 2):S22–S34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan N., Meltz M. L. Induction of nuclear factor kappa B after low-dose ionizing radiation involves a reactive oxygen intermediate signaling pathway. Radiat Res. 1994 Oct;140(1):97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson W. G., Kastan M. B. DNA strand breaks: the DNA template alterations that trigger p53-dependent DNA damage response pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 1994 Mar;14(3):1815–1823. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulverer B. J., Hughes K., Franklin C. C., Kraft A. S., Leevers S. J., Woodgett J. R. Co-purification of mitogen-activated protein kinases with phorbol ester-induced c-Jun kinase activity in U937 leukaemic cells. Oncogene. 1993 Feb;8(2):407–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen C. K., Packer L. Antioxidant and redox regulation of gene transcription. FASEB J. 1996 May;10(7):709–720. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.7.8635688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman M. L., Datta R., Hallahan D. E., Weichselbaum R. R., Kufe D. W. Ionizing radiation regulates expression of the c-jun protooncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Aug;87(15):5663–5666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woloschak G. E., Chang-Liu C. M. Differential modulation of specific gene expression following high- and low-LET radiations. Radiat Res. 1990 Nov;124(2):183–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]