WHEN NAPOLEON’S TROOPS invaded Spain in 1808, the artist Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828) was over 60 years old and already known for his subversive paintings mocking political and religious hypocrisy.1 Napoleon’s military campaigns always included teams of professional artists who painted heroic scenes of famous battles, following instructions from Napoleon’s minister of the arts.2 At the same time, Goya was recording a very different face of war: the struggle of the Spanish people against the invaders and the many horrors of warfare.

During Napoleon’s invasion and occupation of Spain, Goya witnessed what he termed “el desmembramiento d’España”—the dismemberment of Spain—recorded in his haunting series Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War)3 as well as the renowned painting El Tres de Mayo de 1808 (The Third of May, 1808). The French occupation lasted until 1814, when, with Spain in shreds, the Bourbons were restored to power. Throughout this time, Goya visited battle sites, witnessing and recording the Spanish resistance (including the participation of women), atrocities on both sides, and the subsequent famine. Goya’s subjects are anonymous figures from the Spanish under-class, often showing desperate courage in the face of overwhelming force.

In his print series, The Disasters of War, Goya shows war, for the first time, as utterly lacking in glory. His is a vision of war without the consolation of chivalry, religion without mercy, and despair without redemption. Despite the ferocity of his critique, Goya retained a passionate empathy for the suffering he witnessed. His influence resounds in the work of the Expressionists, war photographers, and Picasso’s Guernica. His depictions of patients, torture, and complex psychological states transformed the unspeakable into fit subjects for art.

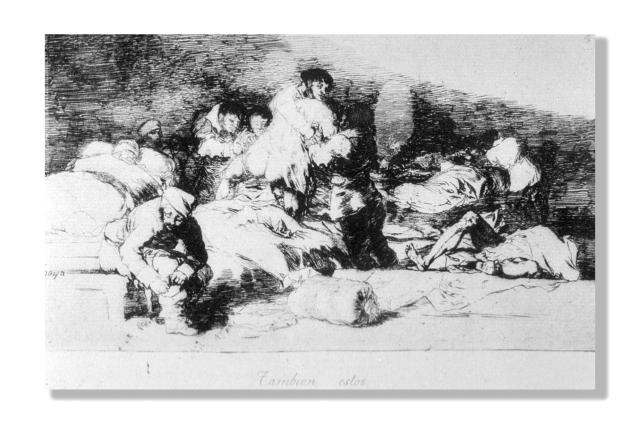

This print, Tambien estos (These Too), shows a roomful of wounded resistance fighters, some in bed and some struggling to stand, dress, and feed themselves. One lies in a grotesque posture, as if scrabbling to rise from the floor or to kick away the sheet hastily thrown over him. Yet if deprived of glory, these men are not without honor. One whose shirttails gape open to bare his backside—the emblem of the vulnerable patient—is being tenderly assisted by others. Of course, in this era before Florence Nightingale’s reforms in the mid-19th century, there would have been no professional nurses to care for the wounded, who largely were left to care for each other. Goya’s composition places them in a harmonious triangle, which balances the scene’s chaos and debilitation.

Goya remained in Spain throughout these “consequencias fatales” (fatal consequences), which he recorded in a series of 80 prints, which critic Robert Hughes calls “the greatest anti-war manifesto in the history of art.”4 None were published in Goya’s lifetime. He died in exile.

Figure 1.

Goya, Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War ), plate 25, Tambien estos (These Too), original etching, drypoint and burin; posthumous, 1862–1863. Fifth edition, late 19th century, 165 mm x 235 mm.

Source. Prints and Photographs Collection, History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Md.

References

- 1.Connell ES. Francisco Goya. New York, NY: Counterpoint; 2004.

- 2.Symmons S. Goya. London, England: Phaidon Press; 1998:233.

- 3.Harris T. Goya: Engravings and Lithographs. Oxford, England: Bruno Cassirer; 1964:215. Catalogue Raisonné; vol 2.

- 4.Hughes R. Goya. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf; 2003:304.