Abstract

Product and marketing innovation is key to the tobacco industry’s success. One recent innovation was the development and marketing of flavored cigarettes as line extensions of 3 popular brands (Camel, Salem, and Kool). These products have distinctive blends and marketing as well as innovative packaging and have raised concerns in the public health community that they are targeted at youths.

Several policy initiatives have aimed at banning or limiting these types of products on that basis. We describe examples of the products and their marketing and discuss their potential implications (including increased smoking experimentation, consumption, and “someday smoking”), as well as their potential impact on young adults.

THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY HAS a long history of innovation in product development. Successful product innovations have included the introduction of filter, menthol, and low-tar cigarettes; changes in cigarette length and circumference (such as ultra long and ultra slim); and changes in cigarette packaging, such as the introduction of the 1950s flip top hard pack, to name a few.1 Innovation in products and marketing is driven by the desire to increase market share and therefore profits. It also may be fueled by industry research into target audience needs, product preferences, and smoking practices and by the need to respond to environmental factors, including litigation, consumer health concerns, public opinion, and tobacco control regulations.

Flavored line extensions of popular cigarette brands—specifically, Camel’s Exotic Blends, Kool’s Smooth Fusions, and Salem’s Silver Label—are a recent tobacco industry innovation.

Although the Wall Street Journal recently called sweet-flavored cigarettes “one of the hottest new product categories in the tobacco industry,”2 industry documents show that tobacco companies have researched and developed flavored cigarettes off and on for decades.3–9 Furthermore, flavored cigarettes such as Kretek International’s Dreams brand and a variety of other flavored tobacco products existed earlier in a “flavor niche” of the tobacco marketplace. However, compared with other flavored cigarettes on the market today, these 3 products, especially Camel Exotic Blends, have been more visible, more available, and, perhaps because of their visibility and availability, more controversial.

These flavored cigarettes may work as innovations intended to increase market share by both meeting product preferences of target audiences and by acting as a means of reaching desirable target audiences (namely, young people) in an environment of growing restrictions. Recent studies show that the 3 flavored products are being used primarily by young people. In surveys conducted in 2004, as many as 20% of smokers 17 to 19 years old had used flavored cigarettes in the last 30 days, whereas only 6% of smokers older than 25 were found to have smoked one of the 3 flavored lines.10 Use was highest for 17-year-olds (19.6%) and 18- to 19-year-olds (20.2%) and lowest for smokers older than 40.11 In terms of gender, 17- to 26-year-old males were more likely than females of the same age to use these products. Among the 3 flavored lines, Camel Exotic Blends was more commonly used than the other two.11 These data raise significant concerns regarding the implications of these products for smoking among youths and young adults.

METHODS

Information presented here was based on review of the scientific and popular literature and collection and analysis of tobacco industry products and promotions. Examples of the products themselves, magazine advertising, and direct mail promotions were drawn from Trinkets and Trash, a surveillance system that collects tobacco industry products and promotions and displays images and information on its Web site.12 From 2003 to 2005, Trinkets and Trash tracked and examined tobacco advertising in 20 general population (but not youth or teen) magazines and collected direct mail promotions from a convenience sample of Trinkets and Trash contributors who had received mail from Camel, Kool, and Salem. A total of 20 packs of flavored cigarettes (12 for Camel, 4 for Kool, 4 for Salem), 20 advertisements related to flavored brands (14 for Camel, 4 for Kool, 2 for Salem), and 21 direct mail pieces promoting the flavored brands (18 for Camel, 2 for Kool, 1 for Salem) were collected. The content of the advertisements, the direct mail pieces, and the packs themselves were analyzed to identify themes. Variables such as the models featured, the type of scene portrayed, and the use of color and font style were considered. In addition, the copy or descriptive words used in all of the pieces were recorded and analyzed. Although the sample may not have included all promotional materials for these flavored brands, we believe it was sufficient for making preliminary observations and for identifying trends and areas for future research.

FLAVORED CIGARETTES AS AN INNOVATION

In 1999, the RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company began marketing Camel Exotic Blends, a line of premium flavored cigarettes with designer wrappings packaged in flat full-color tins. The product line consists of 5 mainstay flavors and additional “special” or “limited time only” flavors featured in promotion with seasons, holidays, or other campaigns. Although initially available only through Camel events or special order, today they may be found in many outlets that sell tobacco, including convenience stores, gas stations, and tobacco stores.13 At least 18 different flavors of Exotic Blends have been introduced since 1999. The blends have used fruit flavors such as berry, lime, coconut and citrus; sweet flavors such as vanilla, cinnamon, chocolate, mint, and toffee; and alcohol flavors such as bourbon.

The Exotic Blends line was followed by flavored extensions of 2 major menthol cigarette brands: RJ Reynolds’ Salem Silver Label, a collection of 4 flavored blends introduced in 2003, and Brown and Williamson’s 4 flavored menthols, Kool Smooth Fusions, a limited edition line introduced in 2004. These 2 brands combined menthol with such flavors as berry, vanilla, and mint. It should be noted that Camel Exotic Blends is the only one of these brands to have continued sales into 2005.

PRODUCT AND BRAND IDENTITY

Package Design

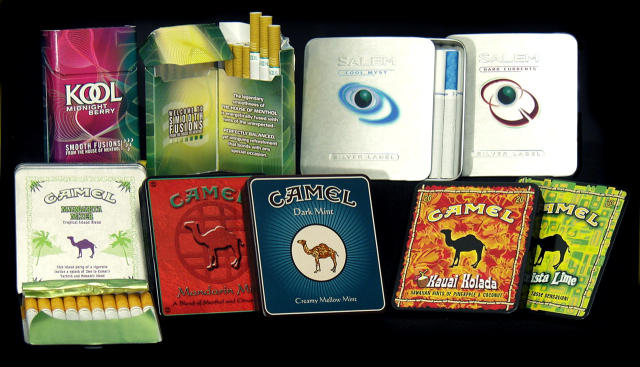

The products under discussion are presented in unique and graphically appealing packages and are designed to create a visual impact (Figure 1 ▶). Package design is a key part of a product’s brand identity and is especially important for cigarettes.14,15 Unlike many other products, cigarette packs are not discarded after being opened but rather are retained and reopened (often in view of others) until the last cigarette has been smoked. The social visibility of the packs and, in the case of distinctive cigarettes, the cigarettes themselves make them “badge products,” wherein the use of the product associates the user with the brand image.15–17 According to a Brown and Williamson executive, consumer response described Kool Smooth Fusions as “a pack to be seen with.”18 Furthermore, the distinctive look of the cigarette pack itself serves as a traveling advertisement of the brand when carried by a smoker; when placed together in a retail setting, the packs act as mini-billboards for the brand at the point of sale.14 Packaging may be particularly important in promoting a new cigarette, especially at the point of sale, where customers choose among the clutter of competitive brands and may meet new brands for the first time.15

FIGURE 1—

Distinctive packaging sets the flavored cigarettes apart. Kool’s Smooth Fusions utilize a completely new cigarette package design—a hard pack that opens up in the middle into 2 halves like a book, with cigarettes held vertically in each side (upper left). For Silver Label, Salem replaced its standard green or black “slide box” hard park with a sleek, silver, slightly curved, tin/aluminum case (upper right). Camel’s Exotic Blends come in embossed foil-wrapped lining paper within elegant and sleek colored tins, following the traditional style of luxury cigarette packaging (bottom row).

Source. Image courtesy of Trinkets and Trash (www.trinketsandtrash.org).

The Camel, Salem, and Kool flavored product lines share a number of other commonalities that also differentiate them from most cigarettes and present them as being new. In addition to innovative packaging, varied leaf blends, and intense flavorings and aromas, the cigarettes themselves have distinctive looks, with designer tipping and wrapping papers that highlight brand logos and match the color and look of the flavor’s pack (Figure 2 ▶). Finally, carefully crafted descriptions of the flavor are provided with the pack to further communicate the identity of both the individual flavor and the flavored brand line overall. For example, the wording on Kool’s Mintrigue pack describes the flavor as “A deeply rewarding menthol experience that tantalizes, yet leaves you guessing as to the secret of its intriguing refreshment.” This “mysterious” sentiment is echoed on the packs of the other Kool flavors, which are described as “alluring,” “enchanting,” and “enticing,” and is again reinforced in the advertising of these flavors (Figure 3 ▶).

FIGURE 2—

The look, smell, and taste of the 3 flavored cigarette lines set them apart from others. These cigarettes highlight brand logos and use designer tipping and wrapping papers that match their brand and flavor image. Cigarettes from left to right: 3 Camel Exotic Blends, 1 Salem Silver Label, 2 Kool Smooth Fusions.

Source. Image courtesy of Trinkets and Trash (www.trinketsandtrash.org).

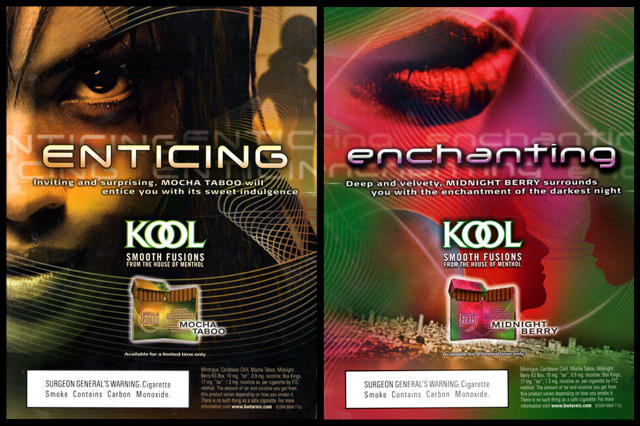

FIGURE 3—

Kool’s sexy Smooth Fusions magazine ads. Kool’s ads use a sexy theme of mystery and intrigue. These ads ran during June through August 2004 in such magazines as Ebony, Latina, Jane, Maxim, Blender, Cosmopolitan, and Playboy.

Source. Image courtesy of Trinkets and Trash (www.trinketsandtrash.org).

Marketing

Advertising is traditionally used to establish brand identity and shape consumers’ attitudes about a brand.15,19

Advertisements for the 2 flavored menthol brands make use of modern type fonts and computer-generated geometric designs and shapes and convey surreal or technological themes. The images for the 5 mainstay Camel Exotic Blends use drawn models with darker features and Middle East–inspired designs, themes, and colors. Their appearance and marketing taps into the current trend toward “new luxury” products that are somewhat more expensive but perceived as being of better quality and taste.20 Promotional messages describe the line as “a collection of sophisticated indulgences,” luxuries that can enhance pleasure. For example, vanilla-flavored Crema is described as delivering a “creamy, indulgent flavor that offers an intriguing and pleasurable smoking experience.”

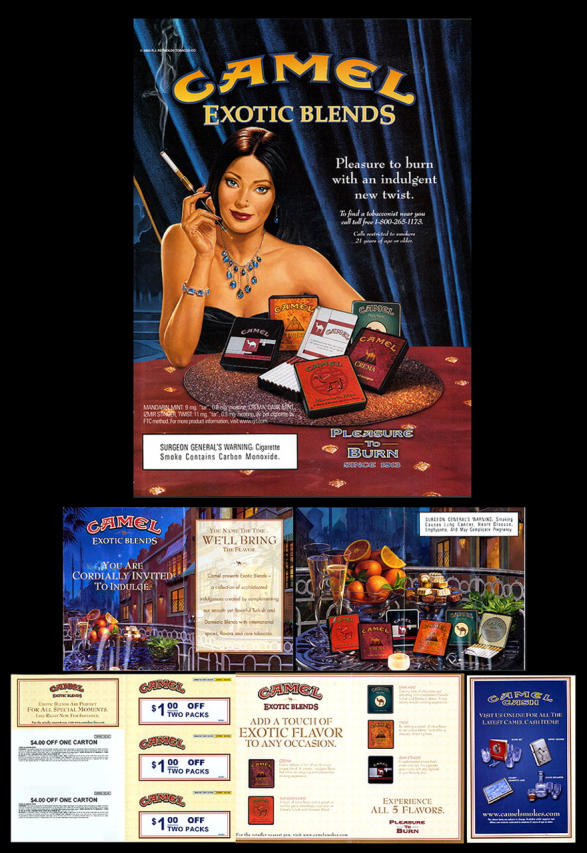

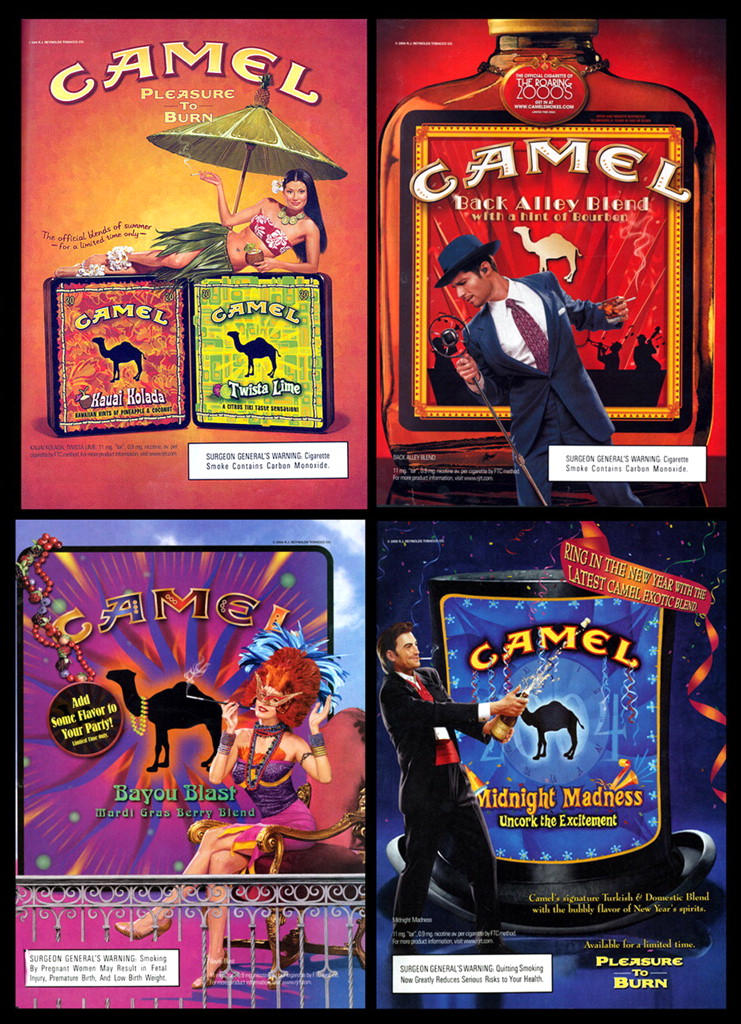

The idea of luxury is reinforced through advertisements portraying Exotic Blends as fine products served on platters and used with other select “indulgences” such as chocolates and champagne (Figure 4 ▶). In contrast, the imagery of the special or “limited edition” Exotic Blends are more colorful and active, as they portray models celebrating special occasions such as Mardi Gras, or enjoying seasons such as summer (Figure 5 ▶). These images frame smoking as a fun activity for special occasions, parties, and use with alcoholic drinks.

FIGURE 4—

Exotic and luxurious marketing images. Marketing images reinforce the overall exotic and luxurious brand identity of Camel’s mainstay Exotic Blends. This magazine ad (top) and direct mail piece (bottom) promote the Exotic Blends as fine products served on platters and used with other select “indulgences” such as chocolates and champagne (bottom). These products are often presented by attractive, luxuriously dressed, and exotic looking models (top). This direct mail piece from Camel (bottom) featured and described each of the five Exotic Blends and invited recipients to “add a touch of flavor to any occasion.”

Source. Image courtesy of Trinkets and Trash (www.trinketsandtrash.org).

FIGURE 5—

Smoking as a fun activity for special occasions. The festive ads for Camel’s “limited edition” Exotic Blends frame smoking as a fun activity for special occasions, parties, and for use with alcoholic drinks. The pineapple- and coconut-flavored Kauai Kolada and the lime-flavored Twista Lime were 2004’s summer blends (upper left). Back Alley Blend (upper right) was the bourbon-flavored featured cigarette of Camel’s Roaring 2000s campaign. Berry-flavored Bayou Blast celebrated Mardi Gras (bottom left), and in December 2003, Midnight Madness was marketed as the New Year’s promotional blend featuring the “bubbly flavor of New Year’s spirits” (bottom right).

Source. Image courtesy of Trinkets and Trash (www.trinketsandtrash.org).

DISSEMINATION OF THE INNOVATION

To diffuse these flavored lines, tobacco companies repeated the images and descriptions of these products across a variety of standard industry diffusion channels, including in-store promotions, magazine ads, direct mail, themed parties at bars/clubs, and interactive Web pages.

In the face of recent marketing restrictions, several studies have noted the tobacco industry’s growing reliance on point-of-sale promotions.21–24 For these flavored products, posters, signs, and other in-store displays—in addition to the packs themselves—encourage purchase.25

Advertising for Camel Exotic Blends was repeatedly found in popular magazines with a predominantly young adult (18–34 years) readership (as reported by individual magazine media kits’ circulation and readership data), including Blender, Cosmopolitan, FHM, GQ, Jane, Maxim, Playboy, and Rolling Stone (many of which may also attract teenaged readers). Smooth Fusions ads were also found in those popular magazines, as well as in Latina and Ebony, magazines aimed, respectively, at Latina and African American women.12

In contrast to magazines, which are visible to the general population, direct mail promotions go only to those on the tobacco industry’s extensive direct mail databases.26 Camel and Kool used direct mail to introduce, promote, and even allow sampling of their flavored blends. The Trinkets and Trash collection received 9 different direct mail pieces from Camel and 2 from Kool between 2003 and 2005 that specifically highlighted their flavored lines. Nine additional Camel pieces promoted Exotic Blends together with the regular blends. Kool used direct mail to introduce Smooth Fusions and provide free trial packs of the new line. One piece from Camel (Figure 4 ▶) presented and described each of the 5 mainstay Exotic Blends. Other Camel pieces promoted limited-time-only seasonal or holiday flavors, such as the New Year’s–themed Midnight Madness.12

Bar and club events are a natural channel for disseminating a “new” version of tobacco products27–29 such as flavored cigarettes. Camel promoted Exotic Blends with free cigarette samples during its 2001–2002 “7 Pleasures of the Exotic” theme party tour and followed this up with its 2004 “Roaring 2000s” bar/club tour to 11 different cities, featuring its bourbon-flavored limited-time cigarette, Back Alley Blend.

Web sites such as Camel’s offer a different kind of dissemination channel—one that is more exclusive (it is a “secured” site, where a login, password, and age verification are needed to explore) and more interactive than print materials. Camel advertisements and direct mail frequently direct readers to the Web site, where Camel devotes a section to promoting the Exotic Blends. The flavors are individually featured and described in various elaborately themed pages. A unique feature of this channel is the “Exotic Blends Store Locator,” a search engine that allows users to type in an address and search for the nearest stores that carry the Exotic Blends.13

IMPLICATIONS

The flavored cigarettes discussed here have come under fire from public health and tobacco control advocates, who say that these “candy flavored” products target youths.2,18,30,31 In addition, they say that flavored cigarettes mask the taste of tobacco (or “sweeten the poison”),10 thereby making it easier for new smokers, 90% of whom are teenagers or younger, to take up the habit.2,18 The tobacco industry denies that these products are targeted at youths and says that the flavors, rather than being candylike, are those that appeal to adults. These cigarettes, the industry claims, reflect a general trend toward flavored products for other adult-oriented products such as liquors and coffee and are made for, tested with, and marketed to adults.2,18

The distinction in target audiences is important for the future of these products. The Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) between the states and the tobacco industry outlawed advertising or promotions targeting youths (younger than 18 years) either directly or indirectly but did not impose significant restrictions on marketing to adults.32 Violation of the MSA through targeting youths could result in substantial penalties for the manufacturers and an end to the sales and marketing of these products. Thus far, tobacco control advocacy efforts and policy initiatives aimed at banning or limiting the sale of flavored products have primarily framed concerns in terms of targeting youths.

Although we agree that these products are indeed enticing to youths and at the very least are being marketed with them in mind, in this discussion we will focus on the tobacco industry’s stated target population of adults, principally young adults, who serve as role models for youths. Indeed, young adults constitute an appealing market for the industry for several reasons. In addition to being the youngest legal targets for the tobacco industry and a group not protected by the MSA, young adults (18–24 years) have some of the highest rates of cigarette smoking in the United States33,34 and are the one group for which smoking prevalence has not fallen in recent years.35 Tobacco companies recognize the importance of the youth and young adult market because brand preferences are established early in life, often with the first cigarette.36 Targeting young adults may be perceived as doubly beneficial in that it both captures 18- to 24-year-olds and indirectly influences teens, who may seek to emulate their older peers.

Whereas previous research found that approximately 90% of smokers began smoking during early adolescence, recent studies suggest that a growing number are initiating smoking as young adults.37–40 A number of factors have been suggested as playing a role in late initiation, including targeted marketing.29,41 In fact, review of previously secret tobacco documents has shown that the tobacco industry sees the process of becoming a smoker as something that begins in the teen years and extends into adulthood.41,42 In other words, getting someone to initiate smoking is just the first step; producing a pack-a-day addicted smoker requires nurturing.

This nurturing and development of a loyal customer depends not just on the degree to which a tobacco brand’s marketing employs images and words that resonate with an audience, but also on how well the product itself meets their needs and smoking preferences. The importance of the product’s blend and taste to its success is not unknown to the industry. Research has shown that tobacco companies have modified product designs to meet target audience preferences,43–45 with women and young people being notable target markets. According to tobacco industry documents, tobacco company research identified mildness, smoothness, sweetness, and less harsh-tasting cigarettes as being important preferences for younger smokers.45 In fact, RJ Reynolds spent much of the 1980s researching and developing new versions of Camel that were more appealing to the young adult smoker. During this time, flavoring was determined to be something that could increase perceptions of smoothness. In this way, flavored cigarettes may be considered as innovations developed for the purpose of gaining market share by building on known product preferences.

Advertising for Camel Exotic Blends frames the smoking of flavored cigarettes as sophisticated and exotic, an indulgence for “special occasions”46 that exemplifies the luxury concept of “smoking less but smoking better.”47,48 These cigarettes may therefore promote another behavior: the growing trend of nondaily or “someday smoking”49 (the highest rate of which is among 18- to 24-year-olds).34 In fact, according to an RJ Reynolds spokesman, Exotic Blends aim not at getting people to start smoking, but rather at adult smokers of competitive brands. “Instead of smoking two packs of mainstream cigarettes daily, we want them to only smoke a few of our cigarettes, but enjoy them more,”47 the spokesman said.

It is too early to estimate the extent to which these flavored products will be adopted or the influence they will have. As indicated in the introduction, recently released findings show that the flavored lines are being smoked by both youths and young adults. Further research into the prevalence of their use and the appeal of their advertising is being conducted. Additional research should focus not only on who is smoking these cigarettes, but also on how, when, and where smokers are using these products. How regularly are they smoked? Are these cigarettes mostly used by current smokers as complements to their existing brand of cigarettes? If so, when, or on what occasions, do smokers decide to use the flavored cigarettes instead? What percentage of flavored-cigarette smokers are new smokers? “Part-time” smokers? Are there people who smoke flavored cigarettes now instead of their regular brand (and instead of quitting)? What do young smokers and nonsmokers think about the advertising and packaging concepts and the product overall? Are the products viewed as less harmful, more attractive, or more acceptable?

It is also unclear to what extent the flavored products—even if they are used as occasional smokes, as their producers say they are intended—might increase sales of and influence attitudes toward the brand in general. Will smoking Camel’s Exotic Blends result in increased market share for regular Camels? Information from an ad agency, Gyro Worldwide, which reports on its Web site that it played an integral role in developing the Exotic Blends launch strategy,25 suggests this might be one of the aims of Camel’s flavored line. According to Gyro, the goal in the creation of the Exotic Blends was to “cast a positive halo across the entire Camel brand by raising product perceptions and dimensionalizing the brand’s unique exotic brand heritage.”25

Although much of the controversy over these flavored cigarettes has centered on their potential to encourage experimentation (while masking the taste of the tobacco) among nonsmokers, smoking initiation is not the only behavior they may influence. The products discussed here offer a variety of tempting tastes and smells that may entice current and transitional smokers to continue smoking, derail quitting attempts, and lure those who have quit smoking to take it up again. These, too, are questions that need to be explored.

It is difficult to gauge how these products are viewed by their respective companies, although it has been noted that in 2002, following the introduction of Exotic Blends, Camel’s sales rose 4% whereas Marlboro’s fell 6%.30 More information is needed about the development of the products (including how flavors are selected and how they are added), about the monetary investment in these products and their advertising, and about their adoption success and market share.

In the meantime, further regulation could work to impede the adoption of these products. As mentioned earlier, the MSA, while outlawing marketing to youths, did not significantly restrict marketing to adults and therefore left open a number of options for the tobacco industry. In keeping with the industry’s history of shifting strategies in response to regulation, public opinion, and other factors,50 the MSA has been followed by increased expenditures for and emphasis on marketing strategies and populations (including young adults) not bound by it, rather than a reduction in overall cigarette promotional spending.23,26,41,42,51,52 Unaddressed strategies include in-store advertising, advertising in magazines that lack a significant youth readership, sponsorship of adult-only events, direct mail, and Internet promotions, all of which have been used in promoting these flavored products. In addition, MSA provisions did not address the content or appearance of cigarettes or their packaging, leaving the door open for the development and promotion of such products as flavored cigarettes, as well as their attractive and innovative packaging.

Public health and tobacco control advocates have long called for government regulation of the design and content of tobacco products, as well as their marketing, as a way of limiting the industry’s ability to maximize both the appeal and addictiveness of their products.53 One provision of recently proposed legislation for the Food and Drug Administration regulation of tobacco calls for banning the use of flavoring other than menthol in cigarettes. Other policies that require plain or generic packaging of tobacco products could limit the appeal of these attractively packaged cigarettes by standardizing tobacco product packaging and design so it is the same from brand to brand.17,54 These policies would protect not only youths but also other susceptible target groups such as young adults.

Whether further regulation of tobacco products, packaging, and marketing will someday be realized or not, the tobacco industry will undoubtedly continue to develop new strategies to ensure its existence and maximize sales within any regulatory environment it faces. For this reason, public health practitioners need to be aware of tobacco industry product development and marketing tactics in order to anticipate, address, and counter their potential impact. Ongoing surveillance of tobacco industry activities is therefore essential.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

We thank Bonnie Kantor and Pressing Issues for their work on the photography and images shown here and on Trinkets and Trash in general. Thanks also to Spiro Yulis for early research on this topic, Michael Greenberg and Gary Giovino for their helpful advice, and Cris Delnevo and Mary Hrywna for their input.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors M. J. Lewis conceptualized the essay and led the writing. O. Wackowski analyzed and described the brand image and dissemination channels and contributed to the writing and editing of drafts.

References

- 1.Borio G. Tobacco timeline. Available at: http://www.tobacco.org/resources/history/Tobacco_History20-2.html. Accessed May 21, 2005.

- 2.O’Connell V. Massachusetts tries to halt sale of “sweet” cigarettes. Wall Street Journal. May 20, 2004:B1.

- 3.Kapuler & Associates. Smokers reaction to a flavored cigarette concept—a qualitative study. Brown and Williamson. January 1984. Bates No. 679235846/5893. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xfb80f00. Accessed May 9, 2005.

- 4.RM Manko Associates. Summary report new flavors focus group sessions. Lorillard. August 1978. Bates No. 85093450/3480. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/blx31e00. Accessed May 9, 2005.

- 5.Jones J. Focus group results on full-flavored menthol cigarettes. Philip Morris. December 6, 1982. Bates No. 2023069326/9332. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ts148e00. Accessed May 11, 2005.

- 6.Distinctly flavored products. Philip Morris. 1990. Bates No. 2075651533. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jhj55c00. Accessed May 11, 2005.

- 7.Frank D, Riehl T. Cigarettes with recognizable flavors—a review. Brown and Williamson. May 10, 1972. Bates No. 621618728/8737. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ffo70f00. Accessed May 10, 2005.

- 8.Bonhomme J, Slone M. Flavored cigarette qualitative research. Philip Morris. July 30, 1993. Bates No. 2048886618/6619. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dko36e0. Accessed May 9, 2005.

- 9.Brown BH, Cantile A, Daniel HG, Johnston ME. 2305 flavor development national pol test 4022 five distinctively flavored cigarettes. June 14, 1977. Bates No. 2057753003/3008. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lno42e00. Accessed May 10, 2005.

- 10.Johnson M. Lawmakers seek ban on flavored cigarettes. Associated Press. May 11, 2005. Available at: http://www.bradenton.com/mld/bradenton/living/health/11623241.htm. Accessed June 29, 2005.

- 11.Giovino GA, Yang J, Tworek C, et al. Use of flavored cigarettes among older adolescent and adult smokers: United States, 2004. Paper presented at: National Conference on Tobacco or Health; May 2005; Chicago, Ill.

- 12.Trinkets and Trash: artifacts of the tobacco epidemic. Available at: http://www.trinketsandtrash.org. Accessed June 6, 2004.

- 13.Camel Exotic Blends store locater. Available at: http://www.smokerswelcome.com/CAM/pub/exotic_blend_retail/exotic_locator.jsp. Accessed December 1, 2004.

- 14.Slade J. Marketing policies. In: Rabin RL, Sugarman SD, eds. Regulating Tobacco. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001:72–110.

- 15.Wakefield M, Morley C, Horan JK, Cummings KM. The cigarette pack as image: new evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2002; 11(S1):i73–i80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wakefield M, Letcher T. My pack is cuter than your pack. Tob Control. 2002;11:154–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham R, Kyle K. The case for plain packaging. Tob Control. 1995; 4:80–86. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ives N. Flavored Kool cigarettes are attracting criticism. New York Times. March 9, 2004. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2004/03/09/business/media/09adco.html?ex=1079939261&ei=1. Accessed March 10, 2004.

- 19.Ogilvy D. Ogilvy on Advertising. New York, NY: Vintage Books; 1983.

- 20.Gardyn R. Oh, the good life. Am Demogr. November 2002:31–35.

- 21.Wakefield MA, Terry-McElrath YM, Chaloupka FJ, et al. Tobacco industry marketing at point of purchase after the 1998 MSA billboard advertising ban. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6): 937–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dewhirst T. POP goes the power wall? Taking aim at tobacco promotional strategies utilized at retail. Tob Control. 2004;13:209–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feighery EC, Ribisl KM, Schleicher N, Lee RE, Halvorson S. Cigarette advertising and promotional strategies in retail outlets: results of a statewide survey in California. Tob Control. 2001;10:184–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruel E, Mani N, Sandoval A, et al. After the Master Settlement Agreement: trends in the American retail environment from 1999 to 2002. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5(S3):S99–S110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gyro Worldwide Case Studies—Camel Exotic Blends. Available at: http://www.gyroworldwide.com/case_camelexotics.htm. Accessed June 27, 2005.

- 26.Lewis MJ, Yulis SG, Delnevo C, Hrywna M. Tobacco industry direct marketing after the Master Settlement Agreement. Health Promot Pract. 2004; 5(S3):S75–S83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.KBA Marketing. Comparative analysis: trend influence marketing vs traditional media. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company. 1994. Bates No. 516067080. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/igz82d00. Accessed July 10, 2003.

- 28.Katz SK, Lavacck AM. Tobacco related bar promotions: insights from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2002;11:92–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sepe E, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Smooth moves: bar and nightclub tobacco promotions that target young adults. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:414–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connolly GN. Sweet and spicy flavours: new brands for minorities and youth. Tob Control. 2004;13:211–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massachusetts takes action against “sweet” cigarettes. Join Together. May 21, 2004. Available at: http://www.jointogether.org/y/0,2521,571058,00.html. Accessed June 5, 2004.

- 32.National Association of Attorneys General. Master Settlement Agreement. Available at: http://www.naag.org/issues/tobacco/index.php?sdpid=919. Accessed November 3, 2005.

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(20): 427–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Prevalence data nationwide tobacco use—2003. Available at: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/age.asp?cat=TU&yr=2003&qkey=4394&state=US. Accessed November 9, 2004.

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(29): 642–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DiFranza JR, Eddy JJ, Brown LF, Ryan JL, Bogojavlensky A. Tobacco acquisition and cigarette brand selection among youth. Tob Control. 1994;3:334–338. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lantz PM. Smoking on the rise among young adults: implications for research and policy. Tob Control. 2003; 12(S1):i60–i70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moon-Howard J. African American women and smoking: starting later. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):418–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wechsler H, Rigotti N, Gledhill-Hoyt J, et al. Increased levels of cigarette use among college students. JAMA. 1998; 280:1673–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cairney J, Lawrence KA. Smoking on campus. An examination of smoking behaviors among postsecondary students in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2002;93(4):313–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: evidence from industry documents. Am J Public Health. 2002; 92(6):908–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Using tobacco-industry marketing research to design more effective tobacco control campaigns. JAMA. 2002;287(22): 2983–2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Connolly GN. Designing cigarettes for women: new findings from the tobacco industry documents. Addiction. 2005;100:837–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cook BL, Wayne GF, Keithly L, Connolly GN. One size does not fit all: how the tobacco industry has altered cigarette design to target consumer groups with special psychological needs. Addiction. 2003;98:1547–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wayne GF, Connolly GN. How cigarette design can affect youth initiation into smoking: Camel cigarettes 1983–93. Tob Control. 2002;11(S1): i32–i39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howington P. Cigarettes’ ads target black teens, critics say. Brown and Williamson defends hip-hop’s use. The Courier-Journal. April 1, 2004. Available at: http://medialit.med.sc.edu/kooltargetsblacks.htm. Accessed November 3, 2005.

- 47.Scott D. Luxury cigarettes targeting cigarettes’ big spenders. Smokeshop Online. Available at: http://www.gosmokeshop.com/0202/cover.htm. Accessed November 23, 2004.

- 48.Ashley B. Prestige sells. Smokeshop Online. Available at: http://www.gosmokeshop.com/0600/merchant.htm. Accessed November 23, 2004.

- 49.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of current cigarette smoking among adults and changes in prevalence of current and some day smoking—United States, 1996–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(14):303–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis MJ, Delnevo CD, Slade J. Tobacco industry direct mail marketing and participation by New Jersey adults. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(2): 257–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Celebucki CC, Diskin K. A longitudinal study of externally visible cigarette advertising on retail storefronts in Massachusetts before and after the Master Settlement Agreement. Tob Control. 2002;11:47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wakefield MA, Chaloupka FJ, Barker DC, Slater SJ, Clark PI, Giovino GA. Changes at the point-of-sale for tobacco following the 1999 tobacco billboard ban. Available at: http://tobaccofreekids.org/reports/stores/adbanpaper0717.pdf. Accessed November 22, 2004.

- 53.Henningfield JE, Benowitz NL, Connolly GN, et al. Reducing tobacco addiction through tobacco product regulation. Tob Control. 2004;13:132–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Slade J. The pack as advertisement. Tob Control. 1997;6:169–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]