Abstract

Objectives. We examined the association between breastfeeding duration and maternal smoking before, during, and after pregnancy.

Methods. Data from the 2000–2001 Oregon Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System were used. Early weaning was defined as not breastfeeding at 10 weeks postpartum.

Results. At 10 weeks after pregnancy, 25.7% of mothers who initiated breastfeeding no longer breastfed. After controlling for confounders, quitters (mothers who quit smoking during pregnancy and maintained quit status after pregnancy) and postpartum relapsers (mothers who quit smoking during pregnancy and resumed smoking after delivery) did not have significantly higher risk for early weaning than nonsmokers. However, persistent smokers (mothers who smoked before, during, and after pregnancy) were 2.18 times more likely not to breastfeed at 10 weeks (95% confidence interval=1.52, 2.97). Women who smoked10 or more cigarettes per day postpartum (i.e., heavy postpartum relapsers and heavy persistent smokers) were 2.3–2.4 times more likely to wean their infants before 10 weeks than were nonsmokers.

Conclusions. Maternal smoking is associated with early weaning. Stopping smoking during pregnancy and decreasing the number of cigarettes smoked postpartum may increase breastfeeding duration.

Breastfeeding is an important contributor to overall infant health, because human breast milk represents the most complete form of nutrition for infants. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that infants be exclusively breastfed for approximately the first 6 months of life.1 One of the United States’ national health goals for 2010 is that at least 75% of new mothers will initiate breastfeeding, at least 50% will continue to breastfeed their infants to 6 months, and 25% will continue to breastfeed their infants at 1 year.2 In 2002, 71.4% of postpartum women in the United States initially breastfed their infants; 35.1% were still breastfeeding to some extent at 6 months.3 To achieve the national goal for duration of breastfeeding by 2010, we must further study the factors affecting breastfeeding duration.

Maternal smoking is an important factor in early termination of breastfeeding. Many studies have found that mothers who smoke are less likely to initiate breastfeeding4–6 and breastfeed for a shorter time than nonsmokers.4–13 Smoking status, however, has been defined differently across studies: some studies have evaluated smoking status during pregnancy5,11,12 or during the postpartum period,5,9,13 whereas many other studies have not defined a time frame for smoking status.6–8,10 To our knowledge, no breastfeeding study has ever considered the changes in smoking patterns before, during, and after pregnancy. We know, however, that many mothers stop smoking during pregnancy to protect their fetuses, and that most resume after delivery.14,15 The duration of breastfeeding may differ between mothers who have never smoked, quitters, postpartum relapsers, and persistent smokers. A thorough understanding of how the mother’s smoking status around the time of pregnancy is associated with duration of breastfeeding is crucial to the design of programs that encourage smoking cessation as well as programs that promote breastfeeding.

Existing studies are also hampered by small sample size and their failure to account for multiple confounding factors.4 Restricted by the information available for analysis, many studies tend to dichotomize smoking status (i.e., smokers vs nonsmokers),6–8,10,11,13 even though studies have found differences in breastfeeding duration between light and heavy smokers.5,9,12,16

In summary, a need has emerged to reevaluate the association between maternal perinatal smoking and the duration of breastfeeding using a population-based sample, controlling for multiple confounding factors, and taking into account the changing pattern of smoking status during the perinatal period as well as the dose–response effect of smoking intensity. We examined 2 main research questions: (1) how do patterns of maternal smoking around the time of pregnancy relate to the duration of breastfeeding; and (2) is the association between maternal smoking and breastfeeding duration modified by the intensity of postpartum smoking?

METHODS

Data and Measures

The Oregon Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) is an ongoing, statewide, population-based surveillance system that collects information on new mothers’ behaviors and experiences before, during, and after pregnancy. Oregon PRAMS was modeled after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s multistate PRAMS program. Data from the 2000 and 2001 Oregon PRAMS were used in this analysis.

Each month, a stratified, systematic random sample of 200–300 new mothers who had delivered live infants within the past 2–6 months was selected from birth certificates. Mothers from racial/ethnic minorities were oversampled. Each selected mother was mailed up to 2 questionnaires; nonresponders were interviewed by telephone. The overall unweighted response rate for the 2000–2001 Oregon PRAMS was 72.6%. Each mother’s response was linked to her child’s birth certificate. Thus the final data included information from both the surveys and the birth certificates.

The 2000–2001 Oregon PRAMS assessed breastfeeding status among 3881 mothers whose babies lived with them at the time of the interview. We examined the prevalence of breastfeeding initiation, defined as a mother breastfeeding or pumping breast milk to feed her baby after delivery. Because 99.7% of the children in the study were at least 10 weeks of age at the time of the interview, we also studied not breastfeeding at 10 weeks (hereafter termed “early weaning”) among mothers who initiated breastfeeding.

Only mothers who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime were asked to provide information on their average daily cigarette consumption for the following 5 time periods: the 3 months before pregnancy; the first, second, and third trimesters during pregnancy; and the time of the survey, which was 10 to 26 weeks after delivery for 97% of all respondents. To explore changes in smoking behavior before, during, and after the time of pregnancy, we used the information on each mother’s smoking status report for all 5 periods and then grouped the mothers into 4 mutually exclusive categories: (1) nonsmokers, who neither smoked during the 3 months before pregnancy nor throughout the pregnancy; (2) quitters, who smoked before pregnancy, quit during pregnancy, and maintained quit status after pregnancy; (3) postpartum relapsers, who smoked before pregnancy, quit during pregnancy, but resumed smoking after pregnancy; and (4) persistent smokers, who reported smoking before, during, and after pregnancy (Table 1 ▶). A mother who had smoked less than 100 cigarettes during her entire life was treated as a nonsmoker in this analysis. We excluded 167 (4.3%) mothers with missing or incomplete smoking pattern data and 63 (1.6%) mothers with smoking patterns that did not fit into 1 of our categories.

TABLE 1—

Patterns of Maternal Perinatal Smoking Status: Oregon PRAMS, 2000–2001

| Self-Reported Smoking Status | |||||||

| Patterns of Perinatal Cigarette Usea | 3 Months Before Pregnancy | 1st Trimester | 2nd Trimester | 3rd Trimester | Postpartum Period | No. of Women,b n = 3047 | Weighted Distribution, % |

| Nonsmokers | N | N | N | N | N | 2465 | 79.1 |

| Quitters | Y | N | N | N | N | 138 | 5.8 |

| Y | N | Y | N | N | 1 | 0.0 | |

| Y | Y | N | N | N | 52 | 1.5 | |

| Y | Y | Y | N | N | 14 | 0.6 | |

| Subtotal | 205 | 7.8 | |||||

| Light postpartum relapsers | Y | N | N | N | Y-low | 50 | 1.8 |

| Y | Y | N | N | Y-low | 40 | 1.1 | |

| Y | Y | Y | N | Y-low | 18 | 0.8 | |

| Y | N | Y | N | Y-low | 3 | 0.1 | |

| Subtotal | 111 | 3.7 | |||||

| Heavy postpartum relapsers | Y | N | N | N | Y-high | 17 | 0.6 |

| Y | Y | N | N | Y-high | 20 | 0.6 | |

| Y | Y | Y | N | Y-high | 9 | 0.5 | |

| Subtotal | 46 | 1.6 | |||||

| Light persistent smokers | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y-low | 74 | 1.7 |

| Heavy persistent smokers | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y-high | 146 | 6.1 |

Note. N = did not smoke during the period; Y = did smoke during the period; Y-low = smoked 1–9 cigarettes per day during the period; Y-high = smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day during the period.

aAmong the total sample of 3881 mothers, we excluded 167 mothers with missing or incomplete smoking pattern data and 63 mothers with smoking patterns that did not fit into 1 of our categories.

bUnweighted sample distribution.

We used only the average daily number of cigarettes smoked at the time of the survey (i.e., postpartum) to examine the dose–response effect of maternal smoking on breastfeeding status. Because of its close proximity to the time of the interview, this time period was less likely to be affected by recall bias. In addition, the number of cigarettes smoked during pregnancy was highly correlated with the number of cigarettes smoked during the postpartum period (correlation coefficients ranged from 0.76 to 0.79 in our data). The postpartum relapsers and the persistent smokers were further divided into light and heavy postpartum smokers (< 10 vs ≥ 10 cigarettes per day). Therefore, a 6-category composite (nonsmokers, quitters, light postpartum relapsers, heavy postpartum relapsers, light persistent smokers, and heavy persistent smokers) was also used to describe perinatal smoking status (Table 1 ▶). This composite reflects both the change in smoking behavior around the time of pregnancy and the intensity of smoking during the postpartum period.

A total of 3557 mothers were included in the analysis of breastfeeding initiation after the exclusion of 63 mothers with smoking patterns that did not fit into 1 of our categories and 261 mothers with missing information on breastfeeding initiation (94) and smoking pattern (167). Subsequently, a total of 3047 mothers were included in the analysis of breastfeeding at 10 weeks, after we excluded 341 mothers who did not initiate breastfeeding, 52 mothers with missing information on the duration of breastfeeding, and 117 mothers with missing information on any control variables mentioned in the following section. In terms of control variables, there were 49 missing values in mother’s education and 56 for pregnancy intention variable; all other control variables had missing values ranging from 0 to 10.

Statistical Analysis

The percentage of mothers who initiated breastfeeding and the percentage of mothers who did not breastfeed at 10 weeks were calculated by perinatal smoking status. For breastfeeding initiation, we only used the 4-category classification of perinatal smoking status. The χ2 statistic was used to check the association between breastfeeding and perinatal smoking status.

The Kaplan-Meier life table method was used to determine whether the cumulative probabilities of weaning at a given week after delivery differed by perinatal smoking status. Mothers who were still breastfeeding at the time of the interview were classified as not having the event of interest (i.e., censored) in this analysis; these women contributed the number of weeks since delivery to the survey time, or 25 weeks, whichever was shorter.

Logistic regression models were estimated to evaluate the probability of not breastfeeding at 10 weeks by smoking status after controlling for confounders. After reviewing the previous literature on the factors affecting postpartum smoking and breastfeeding duration, we adjusted for the following potential confounding variables: mother’s age in years (<20, 20–29, and ≥ 30), years of education (<12, ≥ 12), marital status, race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, other), and health insurance status at time of delivery; child’s gender, parity (1, 2, ≥ 3), and birthweight; pregnancy intention; participation in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); first-trimester initiation of prenatal care; and presence of smokers at home (Table 2 ▶).3,5,9,11,17,18 All control variables were entered simultaneously as indicator variables into the logistic regression models. We considered the possible interactions between maternal smoking, mother’s education, and child’s birth-weight by entering interaction terms into logistic regression models 1 at a time. Interaction terms with P values not significant at the 0.05 level were dropped from the final model. Because the prevalence of not breastfeeding at 10 weeks in this population was far above 10%, the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) would have overestimated the magnitude of the association between breastfeeding and mother’s smoking status. Accordingly, we used the method developed by Zhang and Yu to estimate an adjusted relative risk (RR)19 and the Bootstrap method with 1000 loops to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the RRs.20

TABLE 2—

Sample Characteristics According to Perinatal Smoking Status: Oregon PRAMS, 2000–2001

| Total, (n = 3047) No.a (%)b | Nonsmokers, (n = 2465) No.a (%)b | Quitters, (n = 205) No.a (%)b | Postpartum Relapsers, (n = 157) No.a (%)b | Persistent Smokers, (n = 220) No.a (%)b | |

| No. cigarettes smoked during postpartum period | |||||

| 0 | 2670 (86.9) | 2465 (100.0) | 205 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 1–9 | 185 (5.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 111 (70.7) | 74 (33.6) |

| ≥ 10 | 192 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 46 (29.3) | 146 (66.4) |

| Mother’s age, y | |||||

| < 20 | 345 (9.1) | 222 (7.1) | 38 (10.4) | 39 (25.7) | 46 (16.8) |

| 20–29 | 1741 (56.7) | 1383 (54.4) | 132 (68.6) | 99 (62.8) | 127 (64.1) |

| ≥ 30 | 961 (34.2) | 860 (38.5) | 35 (21.1) | 19 (11.5) | 47 (19.1) |

| Mother’s education | |||||

| < 12 | 792 (19.2) | 629 (16.7) | 41 (16.6) | 43 (30.3) | 79 (39.3) |

| ≥ 12 | 2255 (80.9) | 1836 (83.3) | 164 (83.4) | 114 (69.7) | 141 (60.7) |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 998 (75.1) | 730 (71.8) | 93 (86.8) | 62 (85.6) | 113 (89.2) |

| Hispanic | 910 (16.8) | 845 (19.8) | 32 (7.5) | 16 (5.5) | 17 (4.1) |

| Other | 1139 (8.1) | 890 (8.4) | 80 (5.8) | 79 (8.9) | 90 (6.8) |

| Mother’s marital status | |||||

| Married | 2022 (73.5) | 1803 (81.1) | 90 (49.5) | 50 (37.9) | 79 (44.4) |

| Unmarried | 1025 (26.6) | 662 (18.9) | 115 (50.5) | 107 (62.1) | 141 (55.6) |

| Health insurance status at delivery | |||||

| Yes | 2863 (95.8) | 2299 (95.5) | 196 (96.1) | 155 (99.9) | 213 (96.2) |

| No | 184 (4.2) | 166 (4.5) | 9 (3.9) | 2 (0.1) | 7 (3.8) |

| Child’s gender | |||||

| Female | 1521 (50.5) | 1260 (51.2) | 93 (50.1) | 74 (44.4) | 94 (48.8) |

| Male | 1526 (49.5) | 1205 (48.8) | 112 (49.9) | 83 (55.6) | 126 (51.2) |

| Parity | |||||

| 1 | 1341 (43.2) | 1073 (41.2) | 111 (56.7) | 68 (49.7) | 89 (44.8) |

| 2 | 943 (32.9) | 775 (33.9) | 52 (27.8) | 54 (31.6) | 62 (28.5) |

| ≥ 3 | 763 (23.9) | 617 (24.9) | 42 (15.5) | 35 (18.7) | 69 (26.8) |

| Birthweight below 2500 g | |||||

| Yes | 531 (4.6) | 378 (4.3) | 46 (4.8) | 34 (4.9) | 73 (7.6) |

| No | 2516 (95.4) | 2087 (95.7) | 159 (95.2) | 123 (95.1) | 147 (92.4) |

| Pregnancy intention | |||||

| Intended | 1805 (63.5) | 1562 (67.2) | 101 (56.7) | 61 (52.7) | 81 (40.2) |

| Unintended | 1242 (36.5) | 903 (32.8) | 104 (43.3) | 96 (47.4) | 139 (59.8) |

| WIC participation during pregnancy | |||||

| Yes | 1338 (36.1) | 1006 (31.4) | 109 (45.7) | 91 (61.6) | 132 (56.2) |

| No | 1709 (63.9) | 1459 (68.6) | 96 (54.3) | 66 (38.4) | 88 (43.8) |

| First trimester initiation of prenatal care | |||||

| Yes | 2594 (89.4) | 2120 (90.0) | 172 (91.4) | 126 (86.8) | 176 (83.1) |

| No | 453 (10.6) | 345 (10.0) | 33 (8.6) | 31 (13.2) | 44 (16.9) |

| Presence of smokers at home | |||||

| Yes | 727 (23.0) | 360 (13.2) | 75 (39.8) | 118 (71.7) | 174 (71.9) |

| No | 2320 (77.0) | 2105 (86.8) | 130 (60.2) | 39 (28.3) | 46 (28.1) |

Note. WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

aNumbers of women were from unweighted sample distribution.

bPercentages were weighted to account for survey oversampling, nonresponse, and noncoverage.

To examine the dose–response effect of maternal smoking on early weaning, we first grouped the number of cigarettes smoked during the postpartum period into 5 categories (0, 1–4, 5–9, 10–14, and ≥ 15 cigarettes), which were represented by a score variable with the coding 1–5 and 4 indicator variables (0 was the referent). By entering the score variable into the multiple logistic regression model, we were able to determine whether there was a significant linear trend using the Wald test. The cut-off point (10) for the number of cigarettes smoked postpartum was selected based on the adjusted ORs for 4 indicator variables after collapsing nondifferential categories into 1 category while keeping nonsmokers as a referent.

Database management and statistical analyses were performed with SAS software, version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and SAS-callable SUDAAN.21 Responses were weighted for oversampling, nonresponse, and noncoverage to be representative of all Oregon live-births. All percentages reported here are weighted, and all differences discussed are significant at the 0.05 level, unless noted otherwise.

RESULTS

Of the 3047 women included in the analysis of early weaning, 90.9% were aged 20 years or older, 75.1% were non-Hispanic Whites, 73.5% were married, 95.8% were insured for the delivery, 76.1% were having their first or second birth, 95.4% had delivered a baby who weighed ≥ 2500 g, 63.5% reported the pregnancy as being intended, 63.9% were participating in WIC during the pregnancy, 89.4% had initiated prenatal care during the first trimester, and 77.0% had no smokers at home (Table 2 ▶). Most of the study population (79.1%) did not smoke before, during, or after the pregnancy (i.e., were nonsmokers), 7.8% quit smoking during pregnancy and did not resume after delivery (i.e., were quitters), 5.3% were postpartum relapsers, and 7.8% were persistent smokers (i.e., smoked throughout all the perinatal periods) (Table 1 ▶). Overall, during the postpartum period, 86.9% (nonsmokers plus quitters) of the study population did not smoke, 5.4% smoked less than 10 cigarettes per day, and 7.7% smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day (Table 2 ▶).

Breastfeeding initiation was common in Oregon (91.1%) and was significantly associated with perinatal smoking status: 92.8% of nonsmokers initiated breastfeeding, as did 94.1% of quitters, 82.1% of postpartum relapsers, and 79.0% of persistent smokers (P= .003; data not shown).

At 10 weeks after pregnancy, 25.7% of mothers who had initiated breastfeeding no longer breastfed (Table 3 ▶). The percentage of mothers who were not breastfeeding at 10 weeks was higher among the quitters (33.8%), postpartum relapsers (38.2%), and persistent smokers (56.2%) than among the nonsmokers (21.1%). The unadjusted RR of early weaning was 2.68 (95% CI = 2.07, 3.32) for mothers who smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day during the postpartum period (nonsmokers during the postpartum period were the referent).

TABLE 3—

Association of Early Weaning and Perinatal Smoking: Oregon PRAMS, 2000–2001

| Crude | Adjustedc | ||||

| Patterns of Perinatal Cigarette Use | No. of Womena | % (SE) | Pb | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) |

| Perinatal smoking status | |||||

| Nonsmokers | 2465 | 21.1 (1.3) | <.0001 | Reference | Reference |

| Quitters | 205 | 33.8 (5.4) | 1.60 (1.11, 2.19) | 1.36 (0.85, 1.90) | |

| Postpartum relapsers | 157 | 38.2 (6.6) | 1.81 (1.19, 2.51) | 1.33 (0.80, 2.05) | |

| Persistent smokers | 220 | 56.2 (5.8) | 2.67 (2.11, 3.38) | 2.18 (1.52, 2.97) | |

| No. cigarettes smoked per day during postpartum period | |||||

| 0 | 2670 | 22.2 (1.3) | <.0001 | Reference | Reference |

| 1–9 | 185 | 33.5 (6.2) | 1.50 (0.99, 2.09) | 1.06 (0.59, 1.65) | |

| ≥ 10 | 192 | 59.5 (5.9) | 2.68 (2.07, 3.32) | 2.22 (1.62, 2.96) | |

| Composite perinatal smoking status | |||||

| Nonsmokers | 2465 | 21.1 (1.3) | <.0001 | Reference | Reference |

| Quitters | 205 | 33.8 (5.4) | 1.60 (1.11, 2.19) | 1.37 (0.86, 2.01) | |

| Light postpartum relapsers | 111 | 29.3 (7.2) | 1.39 (0.75, 2.19) | 0.98 (0.46, 1.72) | |

| Heavy postpartum relapsers | 46 | 58.4 (12.8) | 2.78 (1.59, 4.13) | 2.32 (1.13, 3.95) | |

| Light persistent smokers | 74 | 42.9 (11.4) | 2.04 (1.03, 3.19) | 1.54 (0.72, 2.94) | |

| Heavy persistent smokers | 146 | 59.8 (6.6) | 2.84 (2.16, 3.62) | 2.39 (1.69, 3.27) | |

| Total | 3047 | 25.7 (1.3) | . . . | . . . | |

Note. RR = relative risk; CI = confidence interval; . . . = not applicable. Early weaning was defined as not breastfeeding at 10 weeks.

aOnly women who initiated breastfeeding were included.

bP value is from the χ2 test of independence between perinatal smoking status and early weaning.

cAdjusted for mother’s age, education, race/ethnicity, marital status, health insurance status at delivery; child’s gender; birthweight, parity; pregnancy intention, WIC participation, first trimester initiation of prenatal care, and presence of smokers at home.

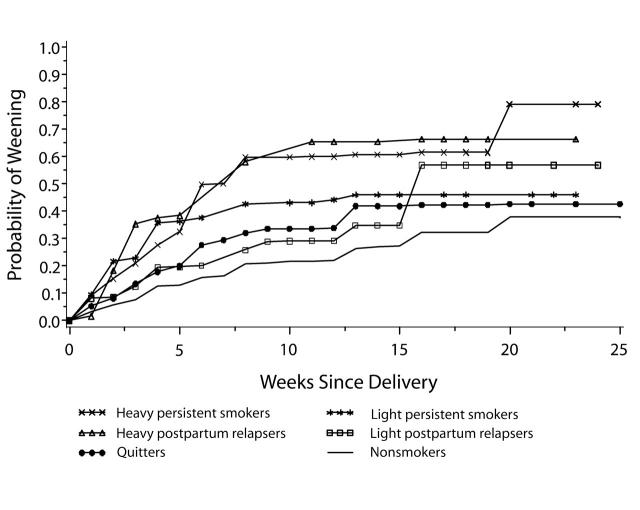

The probabilities of weaning at a specific week also varied by perinatal smoking status (Figure 1 ▶). The estimated probabilities of weaning for nonsmokers were consistently lower than those for smoking mothers. The probabilities of weaning for mothers who were heavy postpartum relapsers and heavy persistent smokers were similar to each other and were consistently higher than those for the mothers with other smoking patterns. The probabilities of weaning for quitters and light postpartum relapsers were similar up to 15 weeks after delivery.

FIGURE 1—

Kaplan–Meier estimates of probability of weaning, by postpartum week and perinatal smoking status.

To better understand the effect of maternal smoking on breastfeeding duration, we ran 3 multiple logistic regression models by entering perinatal smoking status in 3 different forms: (1) the 4-category classification; (2) the number of cigarettes smoked during the postpartum period; and (3) the 6-category classification (Table 3 ▶). After controlling for confounders, we found that the risks of early weaning were higher among quitters, postpartum relapsers, and persistent smokers compared to nonsmokers, but the adjusted RR was significant only among persistent smokers (RR=2.18; 95% CI=1.52, 2.97). Women who smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day during the postpartum period were more likely not to breastfeed at 10 weeks than were nonsmokers (adjusted RR=2.22; 95% CI=1.62, 2.96). This finding was further confirmed when we used the 6-category classification for smoking status. We found that the adjusted RR was significantly higher among heavy postpartum relapsers (2.32; 95% CI=1.13, 3.95) and heavy persistent smokers (2.39; 95% CI=1.69, 3.27) than among nonsmokers (the reference group). Finally, in all 3 models, both infant underweight (RR=1.36; 95% CI= 1.14, 1.60) and presence of smokers at home (RR=1.36; 95% CI=1.02, 1.76) were significant predictors of early weaning after adjusting for other confounders (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Using the data from a population-based survey and birth certificates in Oregon, we found that maternal perinatal smoking is strongly associated with the discontinuation of breastfeeding at 10 weeks. The persistent smokers (i.e., the mothers who smoked before, during, and after pregnancy) were the only group that had a significantly higher risk of not breastfeeding at 10 weeks than nonsmokers; the risk of early weaning among quitters and postpartum relapsers did not significantly differ from nonsmokers. Women who smoked heavily postpartum (≥ 10 cigarettes/day) were 2.3–2.4 times more likely not to breastfeed their infants at 10 weeks than were nonsmokers. These findings indicate that stopping smoking during pregnancy and cutting down on the number of cigarettes smoked during the postpartum period may increase the duration of breastfeeding.

Our results are consistent with the 3 other studies of maternal postpartum smoking.5,9,13 Unlike those 3 studies, however, the present study had a large, population-based sample, and we controlled for multiple potential confounders. Using the detailed history of maternal smoking status before, during, and after pregnancy, we were able to identify persistent smokers and mothers who smoked heavily postpartum, regardless of their smoking status during pregnancy, as the high-risk groups for discontinued breastfeeding at 10 weeks.

These findings may reflect the physiological effect of nicotine on the mother’s hormonal system or on her breasts directly. Andersen et al.22 found that mothers who smoked at least 15 cigarettes per day had a lower basal prolactin concentration and weaned their infants significantly earlier than nonsmokers. Other studies have found that breast milk of smokers has a lower fat content.23 Smokers have lower breast milk volume because of their decreased concentration of prolactin secondary to nicotine intake24 or because of the release of adrenaline, which exerts a central inhibition of oxytocin, a key hormone in the let-down process (i.e., the transporting of milk to the breast duct).25 These findings may also reflect the possible psychological and behavioral impact of smoking on mothers’ intention to breastfeed.26 For instance, mothers who smoke may stop breastfeeding earlier because of their perceived low milk supply27 or because they fear the toxic effects of nicotine and other substances in the milk on their child.28 The breastfed infants of smokers are more likely to have colic or excessive crying than bottle-fed infants or breastfed infants of nonsmokers.29

The present study has several limitations. First is the reliance on self-reported smoking histories and the lack of data on cotinine concentrations to verify the self-reports. Several studies, however, have found that women’s reports of whether they smoked during pregnancy appear to be accurate.30–32 When asked about smoking status by trimester, mothers who smoke generally report reliably on the timing of their smoking during pregnancy.33 Second, we could not clearly determine whether the resumption of smoking preceded early weaning or if the mothers weaned their infants because they intended to resume smoking. Information on mothers’ intention to breastfeed before weaning, which was not available to us, would be helpful in understanding the direction of the relationship. Third, the Kaplan–Meier life table method has the advantage of using all available data on breastfeeding duration and it is a more powerful statistical technique than single-point prevalence. However, the time at which mothers responded to the PRAMS survey may be related to such health behaviors as smoking and breastfeeding. Although we cannot fully eliminate this concern, additional analysis has shown that, at the time of the interview, the responding time measured by postpartum week was not associated with smoking status and breastfeeding (data not shown). Fourth, previous studies have shown that retrospective reports of cigarettes smoked per day are less accurate.30–32 Because of this concern, the actual number of cigarettes smoked was used only for the postpartum period, which may be less susceptible to recall bias given its close proximity to the time of the interview. This concern has precluded our ability to examine whether there is a dose–response effect of cigarettes smoked during pregnancy on the duration of breastfeeding. Maternal smoking status before and during pregnancy by trimester has been added to the 2003 Revised US Standard Certificate of Live Birth.34 Because most states will implement the new birth certificate in the next few years, a need has emerged for methods to analyze this type of data. Fifth, although we were able to control for many confounders, we had no information on maternal employment, which may be associated with the behaviors of interest.3

Our findings have implications for programs that promote smoking cessation during the perinatal period. Many of these programs focus on encouraging women to stop smoking during pregnancy, but do not sufficiently educate women about the importance of remaining nonsmokers after delivery. In situations in which case managers or other staff work with mothers who are trying to quit smoking during pregnancy, the contact all too often ends when the woman has successfully quit before delivery. But follow-up after birth is important to help women remain quitters. Not smoking after birth would make breastfeeding easier for many mothers and would, of course, have other beneficial effects for both the mother and child.

Health care providers can use this study’s findings to counsel women who want to breastfeed. Pregnant women who smoke are often told that quitting will help them have healthier babies, but the adverse consequence of smoking on breastfeeding duration are frequently not mentioned. Our findings suggest that health care providers need to assist and help mothers who have previously smoked before and during (as well as after) their pregnancies to quit smoking during pregnancy and remain nonsmokers after delivery. Mothers who have successfully quit during pregnancy should be encouraged not to resume smoking after the baby is born. Even if mothers smoke during the postpartum period, they should be encouraged to continue breastfeeding while trying to reduce their smoking. By doing so, we may increase breastfeeding.

Acknowledgments

J. Liu was supported by a postgraduate fellowship appointment from the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the US Department of Energy and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Some funding for the Oregon Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System came from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the US Department of Health and Human Services.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the comments of James Gaudino, Bill Sappenfield, and Grace Wyshak on the study, and Zhiwei Yu’s analysis of data on PRAMS breastfeeding at the early stage of this study. We thank Patricia M. Dietz and Brian Morrow at the CDC for offering SAS programs for the bootstrap method. We also thank Tina Kent for her work on Oregon PRAMS.

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was needed for this study.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors J. Liu designed the study, conducted data analysis, and drafted the article. K. D. Rosenberg originated, initiated, and supervised the study. A. P. Sandoval assisted in data management. All authors helped to interpret findings and review drafts of the article.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Work Group on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 1997;100(6):1035–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US. Department of Health and Human Services. Chapter 16. Maternal, Infant, and Child Health. Healthy People 2010 (2nd Ed.): With Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health. Vol 2. Washington, DC: US. Governmental Printing Office; 2000.

- 3.Ryan AS, Zhou W, Acosta A. Breastfeeding continues to increase into the new millennium. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6):1103–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amir LH, Donath SM. Does maternal smoking have a negative physiological effect on breastfeeding? The epidemiological evidence. Birth. 2002;29(2):112–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clements M, Mitchell E, Wright S, et al. Influences on breastfeeding in southeast England. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86:51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whichelow M, King B. Breast feeding and smoking. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1979;54:240–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill PD, Aldag JC. Smoking and breastfeeding status. Research in Nursing & Health. 1996;19:125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horta B, Kramer M, Platt R. Maternal smoking and the risk of early weaning: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:304–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horta B, Victoria C, Menezes A, Barros F. Environmental tobacco smoking and breastfeeding duration. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;146:128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labrecque M, Marcoux S, Tennina S. Association between maternal smoking and breast feeding. Can J Public Health. 1990;81:439–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Letson G, Rosenberg K, WU L. Association between smoking during pregnancy and breastfeeding at about 2 weeks of age. Journal of Human Lactation. 2002;18(4):368–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nafstad P, Jaakkola J, Hagen J, al. e. Weight gain during the first year of life in relation to maternal smoking and breast feeding in Norway. J. Epidemiol Community Health. 1997;51:261–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ratner PA, Johnson JL, Bottorff JL. Smoking relapse and early weaning among postpartum women: Is there an association? Birth. 1999;26(2):76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fingerhut LA, Kleinman JC, Kendrick JS. Smoking before, during and after pregnancy. American Journal of Public Health. 1990;80(5):541–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carmichael SL, Ahluwalia IB, The PRAMS Working Group. Correlates of Postpartum Smoking Relapse: Results from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS). American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;19(3):193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woodward A, Hand K. Smoking and reduced duration of breastfeeding (letter). Medical Journal of Australia. 1988;148:477–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertini G, Perugi S, Pezzati M, Tronchin M, Rubaltelli F. Maternal education and the incidence and duration of breast feeding: a prospective study. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2003;37(4):447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eriksen W. Breastfeeding, smoking and the presence of the child’s father in the household. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:1272–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280(19):1690–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1993.

- 21.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Software for the Statistical Analysis of Correlated Data. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 1997.

- 22.Andersen NA, Lund-Andersen C, Larsen FJ, et al. Suppressed prolactin but normal neurophysin levels in cigarette smoking breastfeeding women. Clinical Endocrinology. 1982;17:363–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hopkinson J, Schanler R, Fraley J, Garza C. Milk production by mothers of premature infants: influence of cigarettee smoking. Pediatrics. 1992;90:934–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vio F, Salazar G, Infante C. Smoking during pregnancy and lactation and its effects on breast-milk volume. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1991;54: 1011–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cross B. The hypothalamus and the mechanism of sympatheticoadrenal inhibition of milk ejection. Jounal of Endocrinology. 1955;12:15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amir LH. Maternal smoking and reduced duration of breastfeeding: a review of possible mechanisms. Early Human Development. 2001;64:45–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powers N. Slow weight gain and low milk supply in the breastfed dyad. Clin. Perinatol. 1999;26:399–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards N, Sims-Jones N. Smoking and smoking relapse during pregnancy and postpartum: Results of a qualitative study. Birth. 1998;25:94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matheson I, Rivrud G. The effect of smoking on lactation and infantile colic (letter). JAMA. 1989;261:42–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.English P, Eskenazi B, Christianson R. Black–white differences in serum cotinine levels among pregnant women and subsequent effects on infant birthweight. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:1439–1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klebanoff M, Levine R, Clemens J, DerSimonian R, Wilkins D. Serum cotinine concentration and self-reported smoking during pregnancy. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;148:259–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verkerk P, Buitendijk S, Verloove-Vanhorick S. Differential misclassification of alcohol and cigarette consumption by pregnancy outcome. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1994;23:1218–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kharrazi M, Epstein D, Hopkins B, et al. Evaluation of four maternal smoking questions. Public Health Reports. 1999;114(1):60–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Center for Health Statistics. 2003 Revisions of the US. Standard Certificates of Live Birth and Death and the Fetal Death Report. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/vital_certs_rev.htm. Accessed October 4, 2004.