Abstract

In the 1930s and 1940s, smoking became the norm for both men and women in the United States, and a majority of physicians smoked. At the same time, there was rising public anxiety about the health risks of cigarette smoking. One strategic response of tobacco companies was to devise advertising referring directly to physicians. As ad campaigns featuring physicians developed through the early 1950s, tobacco executives used the doctor image to assure the consumer that their respective brands were safe.

These advertisements also suggested that the individual physicians’ clinical judgment should continue to be the arbiter of the harms of cigarette smoking even as systematic health evidence accumulated. However, by 1954, industry strategists deemed physician images in advertisements no longer credible in the face of growing public concern about the health evidence implicating cigarettes.

IN 1946, THE RJ REYNOLDS Tobacco Company initiated a major new advertising campaign for Camels, one of the most popular brands in the United States. Working to establish dominance in a highly competitive market, Reynolds centered their new campaign on the memorable slogan, “More doctors smoke Camels than any other cigarette.” This phrase would be the mainstay of their advertising for the next 6 years. Touting surveys conducted by “three leading independent research organizations,” one typical advertisement proclaimed that according to “nationwide” surveys of 113597 doctors “from every branch of medicine,” Camel was the brand smoked by most respondents. It also asserted that this statistic was an “actual fact,” not a “casual claim.”

In reality, this “independent” surveying was conducted by RJ Reynolds’s advertising agency, the William Esty Company, whose employees questioned physicians about their smoking habits at medical conferences and in their offices. It appears that most doctors were surveyed about their cigarette brand of choice just after being provided complimentary cartons of Camels.1

Even without the suspect nature of the data used in the “More Doctors” campaign, the frequent appearance of physicians in advertisements for cigarettes in this and many other ad campaigns is both striking and ironic from the vantage point of the early 21st century. Any association between physicians and cigarettes—the leading cause of death in the United States—is jarring given our current scientific knowledge about the relationship of smoking to disease and the fact that fewer than 4% of physicians in the United States now smoke.2

In 1930s and 1940s, however, smoking had become the norm for both men and women in the United States—and a majority of physicians smoked.3 At the same time, however, rising public and scientific anxiety existed about cigarettes’ risks to health, creating concern among the tobacco companies. The physician constituted an evocative, reassuring figure to include in their advertisements. In retrospect, these advertisements are a powerful reminder of the cultural authority physicians and medicine held in American society during the mid-20th century, and the manner in which tobacco executives aligned their product with that authority.

Even before modern epidemiological research would demonstrate the health risks of smoking at mid-century, there had already arisen considerable concern about the health impact of cigarette use.4 Questions of the moral and health consequences of cigarette smoking that had been prevalent at the beginning of the 20th century still lingered. Although many physicians were unconvinced by this older research, some had begun to recognize a disturbing increase in lung cancer, and some had also started to consider the respiratory and cardiovascular effects of smoking. A common theory held that cancer resulted from chronic irritation to the affected tissue, and many wondered whether cigarette smoke “irritated” lung tissue in this manner.5

Well aware of these concerns—and their impact on cigarette sales—the tobacco companies devised advertising and marketing strategies to (1) reassure the public of the competitive health advantages of their brands, (2) recruit physicians as crucial allies in the ongoing process of marketing tobacco, and (3) maintain the salience of individual clinical judgments about the health effects of smoking in the face of categorical scientific findings.

These elements would be of growing importance as the health effects of smoking came to be more fully elucidated. One aspect of these promotional strategies was to refer directly to physicians in both images and words. We explored how physicians were depicted in these advertisements and how the ad campaigns developed as health evidence implicating cigarette smoking accumulated by the early 1950s.

EARLY MEDICAL CLAIMS

American Tobacco, the leader in the splashy ad campaigns that had made its Lucky Strike brand dominant by the late 1920s, was the first to mention physicians in advertisements. The physician was just one piece of a much larger campaign on behalf of American Tobacco. As cigarette sales grew exponentially in the United States in the early 20th century, Lucky Strikes had become the preeminent brand largely because of its massive promotional efforts. Company president George Washington Hill worked with ad man Albert Lasker to develop a “reason why” consumers should purchase their brand. With no real scientific evidence to back their claims, American Tobacco insisted that the “toasting” process that Lucky Strikes tobacco underwent decreased throat irritation.6 In fact, Lucky Strikes’ curing process did not significantly differ from that of other brands.

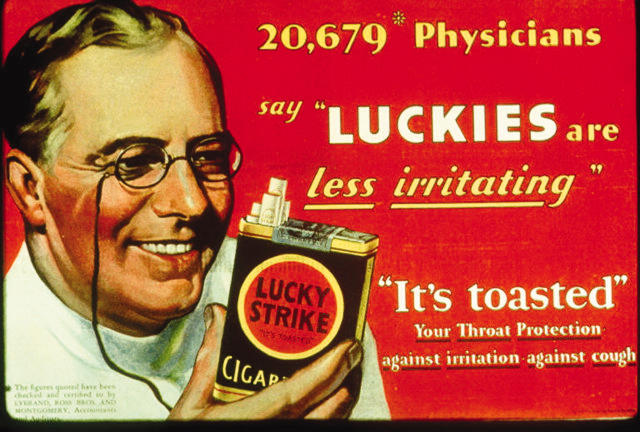

Related campaigns emphasized that “Luckies” would help consumers—especially women, their new market—to stay slim, since they could “Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet.” Along with these persistent health claims, a typical advertisement from 1930 boldly stated that “20,679 Physicians say ‘LUCKIES are less irritating’ ” and featured a white-haired, white-coated doctor with a reassuring smile (Figure 1 ▶).7

FIGURE 1—

Advertisement: “20,679* physicians say ‘LUCKIES are less irritating.’ ”

Source. Magazine of Wall Street . July 26, 1930.

In this manner, American Tobacco advertisements reflected an awareness of ongoing public concern about the potential health effects of cigarette smoking. Referring to a large number of physicians who they claimed backed up the superiority of Lucky Strikes, the ad text noted in small print that their accounting firm had “checked and certified” this number, independently validating the claim.8 Their advertising agency, Lord, Thomas and Logan, had sent cartons of cigarettes to physicians in 1926, 1927, and 1928 and asked them to answer whether “Lucky Strike Cigarettes . . . are less irritating to sensitive and tender throats than other cigarettes.”

Touting the toasting process in the accompanying cover letter, advertising executive Thomas Logan pointed out the virtues of Lucky Strikes and claimed that they had heard from “a good many people” that they could smoke Lucky Strikes “with perfect comfort to their throats.” American Tobacco used the physicians’ responses to this survey to validate their claim that Lucky Strikes were “less irritating,” claiming it confirmed their enduring assertion that their “toasting” process made cigarettes less irritating. Toasting, the advertisement went on to explain, was “your throat protection against irritation—against cough.”9 Although there was no substantive evidence that this process of curing tobacco was superior to the methods used by other companies, American Tobacco made the bold claim and tied it to physicians.

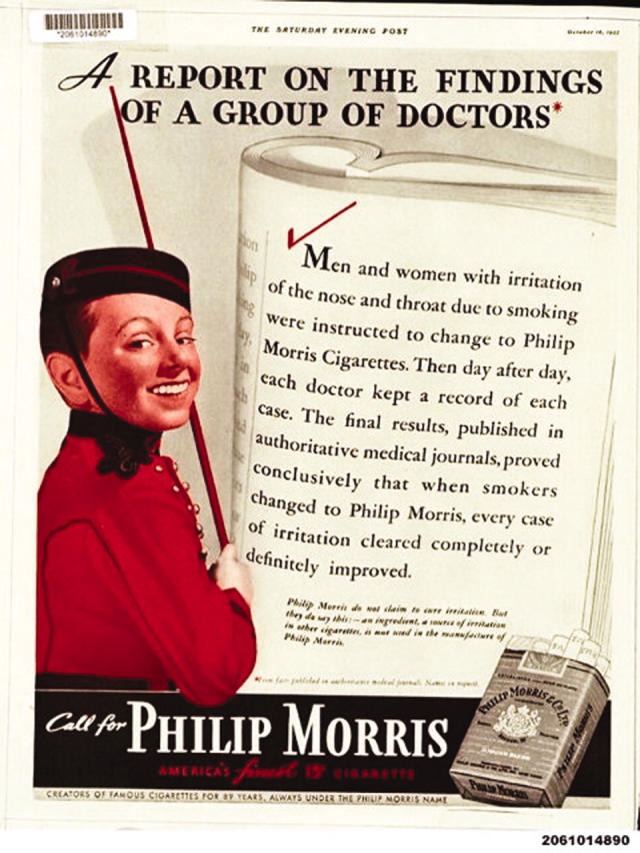

By the mid-1930s, Philip Morris, a newcomer to the market, took the use of health claims a step further, designing a campaign that used a new strategy of referring directly to research conducted by physicians. Both in magazines targeted to the general public and in medical journals, Philip Morris claimed that their cigarettes were proven to be “less irritating.” For example, in a 1937 Saturday Evening Post advertisement, Philip Morris’s hallmark spokesman, bellhop Johnny Roventini, announced that according to “a report on the findings of a group of doctors . . . when smokers changed to Philip Morris, every case of irritation cleared completely and definitely improved” (Figure 2 ▶). The text referred specifically to faithful doctors “day after day. . . [keeping] a record” to “prove conclusively” the decrease in irritation.10

FIGURE 2—

Advertisement: “A report on the findings of a group of doctors.*”

Source. Saturday Evening Post. October 16, 1937.

These “findings” resulted from an aggressive pursuit of physicians and focused on the concept that adding a chemical to their cigarettes, diethylene-glycol, made them moister and less irritating than other brands. As Alan Blum, editor of the New York State Journal of Medicine, explained in his 1983 assessment of cigarette advertisements that had appeared in the journal from 1927 to 1953, Philip Morris—armed with papers written by researchers that the company had sponsored—attempted to use “clinical proof” to establish the superiority of their brand.11 Specifically, Columbia University pharmacologist Michael Mulinos and physiologist Frederick Flinn produced findings (on the basis of the injection of diethylene-glycol into the eyes of rabbits) that became the centerpiece of the Philip Morris claim that diethylene-glycol was less irritating, although other researchers not sponsored by Philip Morris disputed these findings.12

This highly successful campaign made Philip Morris into a major brand for the first time.13 As a 1943 advertisement in the Saturday Evening Post proclaimed, Philip Morris provided “[f]ull reports in medical journals by men, high in their profession—regularly offered to physicians on request.”14

These advertisements used physicians and science to make their particular brand appeal to the broader public while at the same time they curried favor with physicians. Company operatives appeared at medical conventions and in physicians’ private offices, providing physicians with free cigarettes and reprints of scientific articles on the subject. As a 1936 Fortune Magazine profile of Philip Morris & Company made clear:

The object of all this propaganda is not only to make doctors smoke Philip Morris cigarettes, thus setting an example for impressionable patients, but also to implant the findings of Mulinos so strongly in the medical mind that the doctors will actually advise their coughing, rheumy, and fur-tongued patients to switch to Philip Morris on the ground that they are less irritating.15

With careful, deferential appeals to physicians, Philip Morris aimed to gain their approval. The specific positive references to clinical evidence that had appeared in medical journals helped to establish and maintain this connection between physicians and tobacco companies, and between health and cigarettes.

TOBACCO INDUSTRY COURTS DOCTORS

According to a number of accounts, medical professionals—having themselves joined the ranks of inveterate smokers—doubted the connection between smoking and disease after 1930.16 Although hygienic and physiological concerns continued to be voiced, clinical medicine claimed that individual assessment and judgment was required.17 During this era, there was a strong tendency to avoid altogether causal hypotheses in matters so clearly complex. There was—and would remain—a powerful notion that risk is largely variable and thus, most appropriately evaluated and monitored at the individual, clinical level.18

According to this logic, some people could smoke without risk to health, whereas others apparently suffered untoward and sometimes serious consequences. As cigarette smoking became increasingly popular in the early decades of the 20th century, medicine offered no new insight into how best to evaluate such variability other than on an individual post hoc basis. If, and when, an individual developed symptoms, a physician might appropriately advise restricting or eliminating tobacco. As a result, rather than being located within the sphere of public health, cigarette use remained within the domain of clinical assessment and prescription. The tobacco industry would actively seek to keep cigarettes within this clinical domain.

For the tobacco companies, physicians’ approval of their product could prove to be essential, especially since patients often brought smoking-related symptoms and health concerns to the attention of their doctors. Through advertisements appearing in the pages of medical journals for the first time in the 1930s, tobacco companies worked to develop close, mutually beneficial relationships with physicians and their professional organizations. These advertisements became a ready source of income for numerous medical organizations and journals, including the New England Journal of Medicine and the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), as well as many branches and bulletins of local medical associations.19

Coming during the Great Depression, the placement of advertisements in medical journals helped to keep medical organizations financially solvent when resources were scarce. Philip Morris praised physicians in these advertisements with taglines like “Every doctor is a doubter” and “Doctor as judge” as they appealed to physicians’ expert ability to evaluate the evidence, referring them to scientific articles that they claimed illustrated the superiority of their brand. As one such advertisement explained in its entirety in 1939, “If you advise patients on smoking—and what doctor does not—you will find highly important data in the studies listed below. May we send you a set of reprints?”20

Not only, then, did physicians’ findings help to make the Philip Morris brand appear superior in the eyes of the public, but the company also turned to physicians with great effect. Physicians became, through this process, an increasingly important conduit in the marketing process.

RJ REYNOLDS’S MEDICAL RELATIONS DIVISION

Although Philip Morris may have created this strategy—and gained a leg up in the competitive cigarette market—RJ Reynolds became the leading force in soliciting physicians. Reynolds created a Medical Relations Division (MRD) in the early 1940s that became the base of their aggressive physician/health claims promotional strategy. They directly solicited doctors in a 1942 advertisement that appeared in medical journals describing the MRD. Declaring that “[t]he most significant medical data is derived from the every-day records of practising [sic] physicians,” the text asserted “your office record reports in such cases should prove interesting to study.”21

The MRD, including its long-time director, A. Grant Clarke, was in fact a part of RJ Reynolds’s advertising firm, rather than any kind of professional scientific division of the company. The MRD’s mailing address was the side door of the William Esty Advertising Company.22 The work of the MRD focused on promoting Camels mainly through finding and courting researchers to help substantiate the health claims RJ Reynolds made in their advertisements.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Clarke—who had no medical or scientific training—corresponded with many researchers who were pursuing questions relating to smoking and health. The MRD financed research that Reynolds then referred to in advertisements. Rather than emphasizing claims of moistness as Philip Morris had done, RJ Reynolds focused on nicotine absorption, insisting that Camels were the slowest burning of all cigarettes. The safety of nicotine—like the issue of chronic irritation—was a source of ongoing concern; Reynolds maintained that nicotine was “the chief component of pharmacologic and physiological significance.” Camels’ slow burning rate, their advertisements now asserted, decreased nicotine absorption; as a result, Camels offered smokers an advantage over other, faster-burning brands.23

As they made this claim, RJ Reynolds also asked physicians to use the information when advising their patients. They referred to “a number of reports from physicians who recommend Camels” and called on those reading the advertisement to send in their own clinical experiences and to request copies of medical journal articles from the MRD that proved their assertions. The offer served to legitimate RJ Reynolds’s claims. The main article cited did not in fact address Camels specifically, although it did make the claim that slow-burning cigarettes were superior.24 With no clear knowledge about whether nicotine absorption was even an area that should concern smokers, and with very little data showing Camels’ slower absorption, the scientific basis for Reynolds’s claim remained obscure.

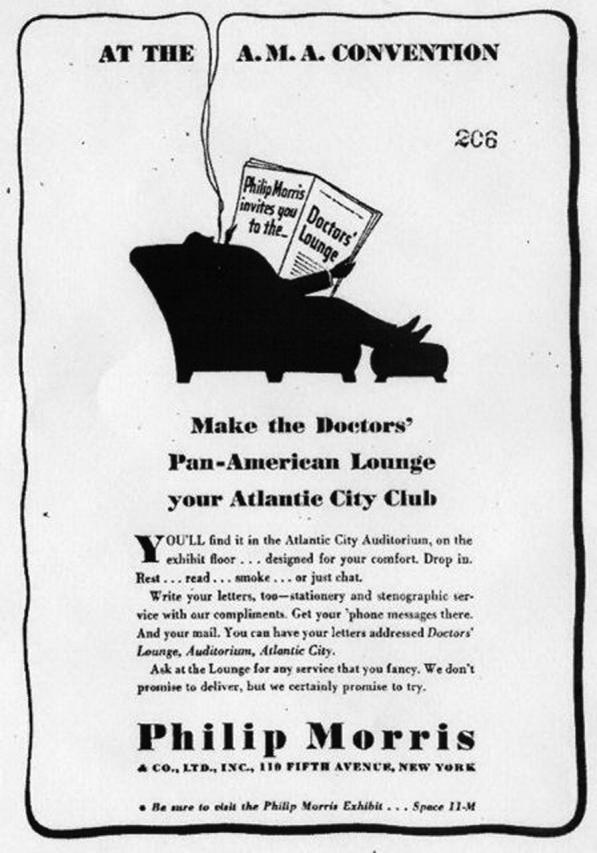

Nonetheless, such health claims would become the basis for the aggressive recruitment of physicians as allies in the promotion of their products and brands. Tobacco companies’ participation in medical conventions provided a clear example of their efforts to appeal to physicians. For example, social commentator Bernard Devoto described the exhibit hall of the 1947 American Medical Association (AMA) convention in Atlantic City, where doctors “lined up by the hundred” to receive free cigarettes.25 At the 1942 AMA annual convention, Philip Morris provided a lounge in which doctors could relax and socialize. The lounge, an advertisement explained, was “designed for your comfort. Drop in. Rest . . . read . . . smoke . . . or just chat”26 (Figure 3 ▶).

FIGURE 3—

Advertisement: “Philip Morris invites you to the . . . Doctor’s Lounge.”26

Besides welcoming physicians to the convention, Reynolds touted their scientific research into cigarettes. In an advertisement that appeared in medical journals across the country in the weeks before the 1942 AMA meeting, Reynolds reiterated their claim that “[t]he smoke of slow-burning CAMELS contained less nicotine than that of the 4 other largest-selling brands tested,” and continued to direct its health theme at doctors. The advertisement also referred to “the interesting features of the Camel cigarette exhibit,” including “the dramatic visualization of nicotine absorption from cigarette smoke in the human respiratory tract” and “giant photo-murals of Camel laboratory research experiments.” At a time when laboratory science had garnered especial admiration, the advertisement linked clinical medicine to the authority of investigative science.27

Along with directly soliciting physicians, the tobacco advertisements portrayed a glowing image of physicians in both medical journals and popular magazines. In advertisements that were precursors to the “More Doctors” slogan, RJ Reynolds specifically featured dedicated physicians serving their country and its soldiers during World War II. As a 1944 advertisement that appeared in Life Magazine entitled “Doctor of Medicine . . . and Morale” illustrated, doctors on the front received hero status:

He wears the same uniform. . . . He shares the same risks as the man with the gun. . . . Yes, the medical man in the service today is a fighting man through and through, except he fights without a gun. . . . [H]e’s a trusted friend to every fighting man. . . .[H]e well knows the comfort and cheer there is in a few moments’ relaxation with a good cigarette . . . like Camel . . . the favorite cigarette with men in all the services.28

With this and similar advertisements, the positive place that physicians held in American culture was both exploited and underlined by RJ Reynolds’s advertising scribes. Linking physicians to wartime patriotism further elevated their status and, with it, Camel cigarettes.

THE “MORE DOCTORS” CAMPAIGN

When the “More Doctors” campaign began in January 1946, it also focused on the respected and romantic image the medical profession had achieved in American society.29 Featuring 6 illustrations of physicians with patients—in the laboratory or sitting back with cigarette in hand—this first advertisement personalized the physician for the readers of such popular magazines as Ladies’ Home Journal and Time.30 Prefaced with the bold statement that “Every doctor in private practice was asked:—family physicians, surgeons, specialists . . . doctors in every branch of medicine,” the advertisement touted the thoroughness of their survey and insisted that “yes, your doctor was asked . . . along with thousands and thousands of other doctors from Maine to California.”

By linking their depiction of physicians to the consumer’s own physician, Reynolds brought immediacy to their claims. Any fears that smoking might be harmful were also easily contradicted by the physician’s being a smoker himself. Admirable, forthright physicians—including the consumer’s own—had “named their choice,” and that choice, the advertisement insisted, was Camels, hands down.

Even though a few of these advertisements did appear in print, the Reynolds advertising department soon realized that they might have overstepped their evidence. With the Federal Trade Commission already challenging suspected health claims in cigarette advertisements, RJ Reynolds toned down their copy, quickly shifting their claim to “113,597 physicians” surveyed rather than all physicians.31

At least some individual physicians questioned the original claim. In a letter to Howard T. Behrman, a physician who had requested “more specific information concerning the survey of physicians’ smoking preference,” RJ Reynolds advertising executive W. T. Smither assured him that the surveying had been thorough and scientific. Explaining that the question about brand preference had been embedded in a survey that included less relevant topics—such as medical journals, medical conventions, and numerous consumer products—Smither emphasized how 3 independent surveys had garnered “similar findings, and in doing so, served to confirm the accuracy of each other.”32

Beyond the questionable methods used to gather data, Reynolds was also careful how they described the survey findings in advertising copy, making sure to avoid conflating doctors’ choice of a cigarette with any belief on their part that Camels were healthier. In their advertisements, they asserted, “Doctors smoke for pleasure just like the rest of us.”33 Internally, Reynolds’s advertising executives cautioned William Esty, their advertising company, to be careful of what they claimed, insisting that “in no way [should] the copy. . . intimate that doctors recommended smoking of CAMELS, [or] that CAMELS are good for health.”34 This cautionary approach reflected the growing industry concern about potential regulation and litigation.35

Even so, the “More Doctors” campaign resonated effectively with American cultural values about contemporary medicine. Throughout 1946, the slogan flooded print, radio, and television media. Doctors were often idealized, as in the 1946 advertisement “I’ll be right over!” Here, a middle-aged physician, in bed in his pajamas, telephone in hand, is about to grab the black bag lying ready on his bedside table and make a middle-of-the-night visit to a patient in need:

24 hours a day your doctor is “on duty.” . . . [I]n his daily routine he lives more drama, and displays more devotion to the oath he has taken, than the most imaginative mind could ever invent. And he asks no special credit. When there’s a job to do, he does it. A few winks of sleep. . . a few puffs of a cigarette. . . and he’s back at the job again.36

This neighborhood family physician is saintly and deserving of trust, representing (as another 1946 advertisement explained) “an honored profession . . . his professional reputation and his record of service are his most cherished possessions.”37 The importance of professional autonomy loomed large, and the industry was eager to sustain this view. As physicians geared up to fight the Truman administration’s national health insurance proposals, their image as loyal and deserving of respect was especially important.38

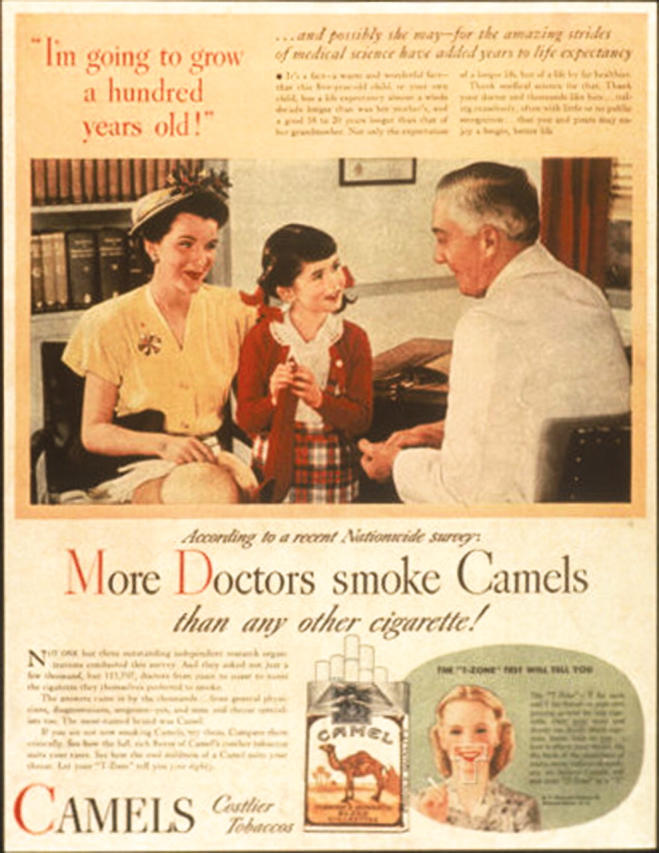

Along with providing images of professional trustworthiness and dedication, the “More Doctors” ad campaign also exploited the popular faith and admiration of medical science and technology. In one such “More Doctors” ad, a 5-year-old girl sits next to her mother in a doctor’s office and proclaims, “I’m going to grow a hundred years old” to the kindly man in white (Figure 4 ▶). Referring to the “amazing strides in medical science [that] have added years to life expectancy,” the advertisement goes on to “thank medical science for that. Thank your doctor and thousands like him. . . toiling ceaselessly. . . that you and yours may enjoy a longer, better life.”39 With medical advances having captured popular imagination, connections drawn between scientific discovery and Camel-smoking doctors added to the appeal of their cigarette of choice.40

FIGURE 4—

Advertisement from the Camels “More Doctors” series: “I’m going to grow a hundred years old!”

Source. Good Housekeeping. July 1946.

MEDICAL AUTHORITY AND TOBACCO

After the initial onslaught of heroic physicians and medical miracles in 1946, the “More Doctors” advertisements in 1947 and 1948 continued to remind readers about the survey as the focus of the advertisements shifted. The main slogan of one such campaign was “Experience is the best teacher.” In this series of advertisements, RJ Reynolds explained that the cigarette shortage created by the war had forced many to smoke whatever brands were available, and this experience, they claimed, had made the superiority of Camels’ quality clearly evident. The smoker was able to tell the difference between brands, and such “experience” translated to other areas where someone might have know-how. When the slogan appeared in magazines like Life and Saturday Evening Post, the “experience” cited might be that of a talented celebrity athlete able to discern quality in his or her sport. In medical journals, the references were to famous scientific researchers. These advertisements championed physicians and medicine and reminded their audience again that “More doctors smoked Camels” as they also continued to praise science.41

But the idea of “experience” also figured into another prevalent theme communicated in RJ Reynolds’s advertising—that of individual authority, both the physician’s and the individual consumer’s. The question of throat irritation so central to many 1920s and 1930s ad campaigns again emerged here as RJ Reynolds introduced a “mildness” theme. With the central claim that Camels did not irritate the throat, Reynolds featured both the physician-researcher and the everyday smoker to convince readers of Camels’ mildness.

In July 1949 issues of both local and national medical journals, RJ Reynolds asked, “How mild can a cigarette be?” In answering this question, the advertisement juxtaposed a “doctors report”—illustrated with a physician, cigarette in hand and head mirror strapped around his brow—with a “smokers report”—illustrated with a smiling “Sylvia MacNeill, secretary.” Physicians, the advertisement explained, had concluded after scientific investigation that there was “not one single case of throat irritation” from smoking Camel cigarettes. In fact, “noted throat specialists” had conducted “weekly examinations” of patients in making this determination. Reynolds used this depiction of careful, clinical observation to substantiate their health claim (Figure 5 ▶).42

Figure 5—

Advertisement: “How mild can a cigarette be?”

Source. Ohio State Journal of Medicine. July 1949;45:670.

The advertisement went beyond medical authority, however, asserting that smokers didn’t even have to take their physicians’ word for it. Instead, they could take their “own personal 30-day test,” as Sylvia MacNeill had done. She concluded that she “knew” that “Camels are the mildest, best-tasting cigarette I ever smoked.” Advertisements in popular magazines took smokers’ ability to judge for themselves even further, with Elana O’Brian, real estate broker, declaring in a typical example, “I don’t need my doctor’s report to know Camels are mild.” The advertisement underlined her assertion with photos of 6 other smokers from various walks of life under the heading “Thousands more agree!”43

In another example, Anne Jeffreys, a stage and screen star, insisted, “The test was fun and it was sensible!” Parallel to earlier solicitation of physicians’ opinions, in this series of advertisements RJ Reynolds requested that smokers determine the safety of Camels on their own and praised their acumen. With some advertisements calling on smokers to “Prove it yourself!” and even guaranteeing a money-back guarantee for dissatisfied customers, Reynolds insisted on the superiority of their product.44 These advertisements worked to subvert the emerging population-based epidemiological findings by emphasizing the primacy of “individual” judgment.

By 1952, advertising copy went beyond the typical individual smoker to emphasize the sheer volume of people who chose Camels as their cigarette. Highlighting that Camel was “America’s most popular cigarette by billions,” the ad copy mentioned that “long before Camel reached those heights, repeated surveys showed that more doctors smoke Camels than any other cigarette.”45 The cigarette’s popularity in itself became a selling point: how could so many people be wrong? And physicians’ cigarette choice served to confirm this popularity. As the heading of a similar advertisement explained, “The doctors’ choice is America’s choice.”46

THE DISAPPEARING DOCTOR

Ultimately, however, the use of physicians in Camel advertisements could not be sustained as the health evidence against cigarettes accumulated. When disturbing scientific results connecting lung cancer and cigarettes began to emerge, Camel advertisements shifted away from physicians’ judgment and authority. In 1950, the publication of the now-famous work of Evarts Graham and Ernst Wynder in the United States—as well as that of A. Bradford Hill and Richard Doll in the United Kingdom—showed that there was cause for alarm.47 The reporting of their findings connecting lung cancer to cigarette smoking in national magazines like Time and Reader’s Digest—and the corresponding declines in sales and stock prices—forced tobacco executives to assess strategies for responding to growing medical and public concerns about their product.48

By 1953, when Wynder, Graham, and their colleague Adele Croninger published laboratory findings confirming that cigarettes were carcinogenic, scientific findings constituted a critical threat to the industry.49 Tobacco executives were well aware both of these findings and of the public attention they were receiving, and their statements and actions reflected an understanding that this new scientific evidence constituted a full-scale crisis for their corporations.

Most notably, company executives realized that they would have to work together in the face of the scientific evidence. Although each company still sought an advantage over its competitors, the new health evidence threatened the future of the entire industry. In December 1953, the tobacco executives met to devise a joint strategy. They hired prominent public relations firm Hill & Knowlton to aid in this effort. As a planning memo makes clear, health claims were considered to be no longer viable. According to Edward Dakin, a Hill & Knowlton executive, it would be critical to

Develop some understanding with companies that, on this problem, none is going to seek a competitive advantage by inferring to its public that its product is less risky than others. (No claims that special filters or toasting, or expert selection of tobacco, or extra length in the butt, or anything else, makes a given brand less likely to cause you-know-what. No “Play-Safe-with-Luckies” idea—or with Camels or with anything else.)50

Hill & Knowlton’s advice was that the industry as a whole must desist from health claims that had been a centerpiece of the advertising that featured physicians. Such claims, the agency now contended, would now draw attention to the “health scare,” as they professed to call it.51

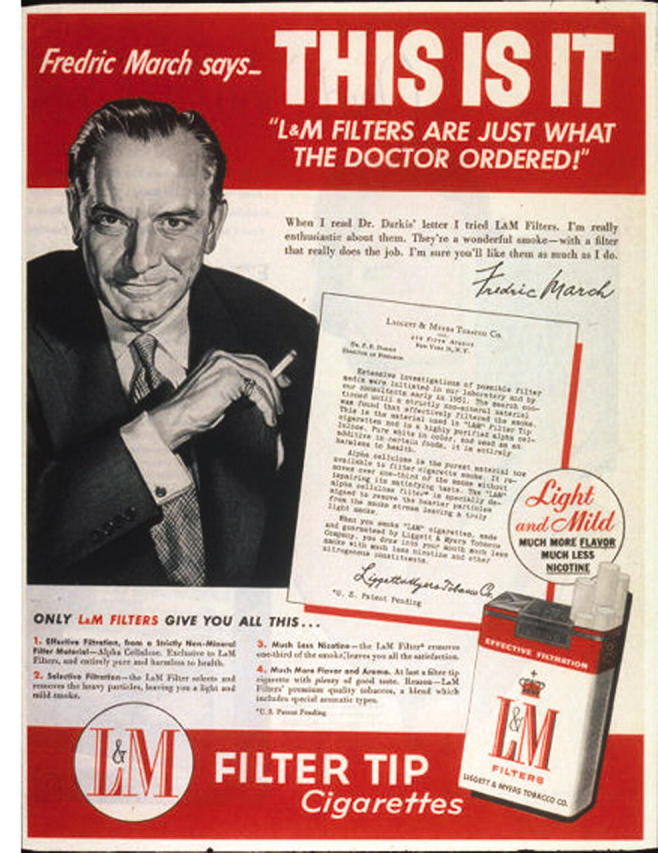

In popular magazines, the last notable reference to doctors in an advertisement came in 1954. After the other tobacco companies had left such marketing techniques behind, Liggett and Myers (which had declined participation in the joint industry program directed by Hill & Knowlton) made the claim that their L&M filter cigarette was “Just what the doctor ordered!” In a typical advertisement that appeared in a February issue of Life magazine, Hollywood star Fredric March made this assertion after having read the letter written by a “Dr Darkis” that was inset into the advertisement. Darkis explained in this letter that L&M filters used a “highly purified alpha cellulose” that was “entirely harmless” and “effectively filtered the smoke” (Figure 6 ▶).

FIGURE 6—

Actor Fredric March in an advertisement for L&M Filters: “This Is It.”

Source. Life Magazine . February 22, 1954.

Dr Darkis was in fact not a medical doctor at all but a research chemist, yet another example of misrepresentation in a tobacco ad.52 More significantly, this use of implicit doctor endorsement of cigarettes would not occur again in American advertising after this campaign. Much in the way that the industry had used doctors to reassure smokers in the 1940s, filter cigarettes were becoming the industry’s new strategy for appealing to consumers, whose concerns about the health risks of smoking would be repeatedly confirmed by new research studies. In 1950, filter cigarettes were 2% of the US cigarette market; by 1960, they were 50%.53

In medical journals, the last-gasp attempt by a tobacco company to ally itself with physicians came in 1953, when the Lorillard Company appealed to physicians as they promoted their new filter cigarette, Kent. These advertisements queried, “Have you tried this experiment, doctor?” and “Why is it, doctor, that one filter cigarette gives so much more protection than any other?” One advertisement mentioned how “thousands” of physicians at a recent AMA convention witnessed “a convincing demonstration. . . [of] the effectiveness of the MICRONITE FILTER” and included photos of the experiment demonstrated there. In their marketing of Kent, Lorillard had created a campaign reminiscent of those designed by Philip Morris and RJ Reynolds in the 1930s and early 1940s.54 Just as in those earlier advertisements, Lorillard called on physicians to interpret scientific results using their individual, clinical judgment. But the swift and vehement reaction to these advertisements clearly illustrated how the social and scientific climate had shifted. A 1954 JAMA editorial labeled the reference to physicians and the AMA convention an “unauthorized and medically unethical use of the prestige and reputation of the American Medical Association.”55 No longer could tobacco companies count on physicians to serve as public advocates of their product.

In fact, in 1953 JAMA had decided to stop accepting cigarette advertisements in its publications and banned cigarette companies from exhibiting their products at AMA conventions.56 After conducting its own survey of physicians, the AMA explained in a letter to tobacco companies that “a large percentage of physicians interviewed expressed their disapproval” of cigarette advertisements in medical journals. Other JAMA advertisers had come to dislike having their products appear next to cigarette advertisements as well.57 With the AMA publicly condemning the Kent ad campaign in 1954 as “hucksterism,” it became even more clear to tobacco companies that the purported allegiance with physicians was no longer feasible or effective.

One additional indicator of the growing medical disdain for cigarettes was the very fact that many physicians who followed the emerging health evidence began the process of giving up smoking. According to one study of physicians’ smoking practices in Massachusetts, nearly 52% had reported being regular smokers in 1954 (over 30% reported smoking at least a pack per day); just 5 years later, only 39% were regular smokers. Additionally, only 18% now reported consumption of a pack or more per day.58

Although the industry would continue to solicit physicians with materials disputing the relationship between smoking and disease and would also seek out physicians who doubted the harmfulness of cigarettes in order to undermine emerging scientific findings, such efforts would be greeted with rising skepticism.59 The era of explicit use of physicians and health claims to promote smoking had ended even though the AMA would not publicly acknowledge the harms of cigarette smoking until 1978.60 The smoking physician had become a visual oxymoron. The industry would turn to new images and more sophisticated strategies to hawk their dangerous product.

Acknowledgments

A. M. Brandt is the recipient of the William Cahan Distinguished Professor Award, granted by the Flight Attendants Medical Research Institute. This award provides financial support for research.

A. M. Brandt served as a consultant and expert witness on behalf of the Department of Justice in USA v Philip Morris et al. M. N. Gardner also served as a consultant in the case.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors Both authors developed, researched, and wrote the article. M. N. Gardner is principal author and A. M. Brandt is coauthor.

Endnotes

- 1.See Crist P., W. E. Marple, S. J. Kaczynski, and T. L. Abrams, “re. Jones/Day Liability Summary (‘Corporate Activity Project’),” pp. 379–381, 1986, Bates No. 681879254/9715, available at tobaccodocuments.org/ness/37575.html (accessed November 12, 2005, as were all Internet citations); “[Memo to John W. Hill] Re. RJR Claim of Doctor’s Use of Camels,” J. J. D. to John W. Hill, December 14, 1953, Wisconsin Historical Society, John W. Hill Papers, Box 110, Folder 10.

- 2.Nelson D. E., G. A. Giovino, S. L. Emont, et al., “Trends in Cigarette Smoking Among US Physicians and Nurses,” Journal of the American Medical Association 271 (1994): 1273–1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snegireff L. S. and O. M. Lombard, “Survey of Smoking Habits of Massachusetts Physicians,” New England Journal of Medicine 250 (24) (1954): 1042–1045; “The Physician and Tobacco,” Southwestern Medicine 36 (1955): 589–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lombard H. L. and C. R. Doering, “Cancer Studies in Massachusetts, II: Habits, Characteristics and Environment of Individuals With and Without Cancer,” New England Journal of Medicine 196 (10) (1928): 481–487; F. L. Hoffman, “Cancer and Smoking Habits,” Annals of Surgery 93 (1931): 50–67; A. Ochsner and M. DeBakey, “Symposium on Cancer: Primary Pulmonary Malignancy, Treatment by Total Pneumonectomy. Analysis of 79 Collected Cases and Presentation of 7 Personal Cases,” Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics 68 (1939): 435–451. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson J., The Dread Disease: Cancer and American Culture (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1987). See Ochsner and DeBakey, “Symposium on Cancer,” for a direct reference to “chronic irritation” and cancer (p. 446).

- 6.See “Good Taste in Advertising,” Fortune 1 (1930): 60–61, and “The American Tobacco Co.,” Fortune 14 (1936): 96–102, 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchand R., Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 21–22; R. Sobel, They Satisfy: The Cigarette in American Life (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books; 1978), 101; G. H. Allen, “Albert Davis Lasker,” Advertising and Selling 19 (1932): 21–22, 36–37.

- 8.In a report to the Federal Trade Commission, American Tobacco Company detailed this survey. See American Tobacco Company, “United States of America, Federal Trade Commission: Memorandum Submitted by the American Tobacco Company,” pp. 18–22, 80–89, 1976, Bates No. 980306396/6603, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rum85f00.

- 9.Lucky Strike advertisement, from Golden Book 12 (70) (1930), available at http://tobaccodocuments.org/pollay_ads/Luck11.07.html.

- 10.Morris Philip, “Report on the Findings of a Group of Doctors Call for Philip Morris,” October 16, 1937, Bates No. 2061014890, available at http://tobaccodocuments.org/ads_pm/2061014890.html.

- 11.Blum A., “When ‘More Doctors Smoked Camels’: Cigarette Advertising in the Journal,” New York State Journal of Medicine 83 (1983): 1347–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulinos M. G. and R. L. Osborne, “Irritating Properties of Cigarette Smoke as Influenced by Hygroscopic Agents,” New York State Journal of Medicine 35 (1935): 1–3, and “Pharmacology of Inflammation, III: Influence of Hygroscopic Agents on Irritation From Cigarette Smoke,” Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine 32 (1934): 241–245. For dispute on their findings, see internal memos from H.R. Hanmer, research director at American Tobacco, to C. F. Nailey (August 29, 1935, Bates No. 90516197711978, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/noj54f00) and to E. Bogen (December 27, 1935, Bates No. 950143321/3328, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pko54f00). Howard C. Ballenger had findings that contradicted Mulinos in “Irritation of the Throat From Cigaret Smoke: A Study of Hygroscopic Agents,” Archives of Otolaryngology 29 (1939): 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- 13.“Philip Morris & Co.,” Fortune, March 1936, pp. 106–112, 114, 116, 119.

- 14.Morris Philip advertisement, from Saturday Evening Post, September 25, 1943, available at http://tobaccodocuments.org/pollay_ads/Phil03.04.html.

- 15.“Philip Morris & Co.,” 116.

- 16.Werner C. A., “The Triumph of the Cigarette,” American Mercury 6 (1925): 419–420; W. M. Johnson, “The Effects of Tobacco Smoking,” American Mercury 25 (1932): 451–454; A. G. Ingalls, “If You Smoke,” Scientific American 154 (1936): 310–313, 354–355. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burnham J. C., “American Physicians and Tobacco Use: Two Surgeons General, 1929 and 1964,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 63 (Spring 1989): 1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.See Aronowitz R. A., Making Sense of Illness: Science, Society and Disease (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 111–144.

- 19.Wolinsky H. and T. Brune, The Serpent on the Staff: The Unhealthy Politics of the American Medical Association (New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 1994), 145–147; “When ‘More Doctors Smoked Camels,’ ” 1347.

- 20.Morris Philip, “If You Advise Patients on Smoking,” August 1939, advertisement, Bates No. 2061011925, available at http://tobaccodocuments.org/ads_pm/2061011925.html.

- 21.Reynolds RJ, “The Medical Relations Division of Camel Cigarettes Believes That,” September 1942, advertisement, available at http://tobaccodocuments.org/pollay_ads/Came02.16.html.

- 22.Crist et al, “re. Jones/Day Liability Summary,” 379–381.

- 23.Reynolds RJ, “When You Record the Effectiveness of Nicotine Control-Less Nicotine in the Smoke. Camel—The Cigarette Of Costlier Tobaccos,” July 1942, advertisement, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sgt78d00.

- 24.Crampton C. W., “The Cigarette, the Soldier, and the Physician,” The Military Surgeon 89 (1941): 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeVoto B., “Doctors Along the Boardwalk,” in Harper’s magazine (1947), reprinted in DeVoto, The Easy Chair (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1955), 91.

- 26.Morris Philip, “At the AMA. Convention,” June 6, 1942, Bates No. 1003071327, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fvm02a00.

- 27.Reynolds RJ, “Camel Invites You to Enjoy the Interesting Features of the Camel Cigarette Exhibit at the AMA. Convention—June 8 to 12,” June 1942, Bates No. 502596871/6871, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cst78d00.

- 28.Reynolds RJ, “Camels Costlier Tobaccos,” advertisement, available at http://tobaccodocuments.org/pollay_ads/Came14.17.html. This ad appeared in Saturday Evening Post, Life, and Colliers in May 1944, and similar ones appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine and the Journal of the American Medical Association.

- 29.Burnham J. C., “American Medicine’s Golden Age: What Happened to It?” Science 215 (1982): 1474–1479. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Reynolds RJ, “Every Doctor in Private Practice Was Asked. According to a Recent Nationwide Survey: More Doctors Smoke Camels Than Any Other Cigarette!” March 1946, available at http://www.trinketsandtrash.org/results.asp. The Trinkets and Trash Web site notes that the ad appeared in the March 1946. Ladies Home Journal.

- 31.See letters from Tiemann Helen, secretary to William Esty, to the RJR Advertising Department dated January 9, 1946. (Bates No. 502597537, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ijs78d00) and December 26, 1945 (Bates No. 502597519, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qis78d00).

- 32.Letter from Smither W. T., RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company, to Dr Howard T. Behrman, February 22, 1946, Bates No. 2022238658/8660, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rtx74e00.

- 33.Reynolds RJ, “Every Doctor in Private Practice Was Asked.”

- 34.Smither W. T., “Memorandum of Visit to William Esty,” June 10, 1946, Bates No. 501889543, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/guv29d00.

- 35.See also Welch James T. to A. G. Clarke, February 4, 1952, Bates No. 502400834, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/blc19d00.

- 36.Reynolds RJ, “More Doctors Smoke Camels,” advertisement, available at http://tobaccodocuments.org/pollay_ads/Came18.17.html. Internal RJ Reynolds records note that this advertisement appeared in Life, Look, Ladies’ Home Journal, Colliers, and Country Gentleman under the heading “I’ll Be Right Over!” RJ Reynolds, “According to a Recent Nationwide Survey: More Doctors Smoke Camels Than Any Other Cigarette!” May and June 1946, advertisement, Bates No. 502470699, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jvj88d00.

- 37.Reynolds RJ, “The Doctor Makes His Rounds: According to a Recent Nationwide Survey: More Doctors Smoke Camels Than Any Other Cigarette!” August and September 1946, Bates No. 502470743, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bxj88d00.

- 38.Compulsory Health Insurance: The Continuing American Debate, ed. R. L. Numbers (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1982).

- 39.Reynolds RJ internal document, Bates No. 502470717, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bwj88d00.

- 40.See De Kruif P., Microbe Hunters (New York: Blue Ribbon Books, 1926), and B. Sokoloff, The Miracle Drugs (Chicago: Ziff-Davis Pub Co, 1949).

- 41.Reynolds RJ, “Experience Is the Best Teacher. Sir Charles Bell,” March 1947, Bates No. 502470841, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/moj88d00, and RJ Reynolds, “Experience Is the Best Teacher. Mildred O’Donnell,” May and June 1947, Bates No. 502470864, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jpj88d00.

- 42.Reynolds RJ, “How Mild Can a Cigarette Be?” July 1949, Bates No. 502471375, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nfj88d00; RJ Reynolds, “How Mild Can a Cigarette Be?” July 1949, Bates No. 502598073, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ztr78d00. RJ Reynolds had also had a related long-term campaign in their ads, asking consumers to take a “30-day test” of their “T-Zone” so that they could decide for themselves about the effect of Camels on their throat.

- 43.Reynolds RJ, “Not One Single Case of Throat Irritation Because of Smoking Camels! Noted Throat Specialists Report on 30-Day Test of Camel Smokers,” January 1949, Bates No. 502598158, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/flr78d00.

- 44.Reynolds RJ, “30-Day Smoking Test Proves Camels Mildness!” November 20, December 4, 6, 7, 1948, January 1949, Bates No. 502597957, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/obs78d00.

- 45.Display ad, New York Times, August 25, 1952, p. 6.

- 46.Display ad, New York Times, June 16, 1952, p. 10.

- 47.Wynder E. L. and E. A. Graham, “Tobacco Smoking as a Possible Etiologic Factor in Bronchiogenic Carcinoma: A Study of 684 Proved Cases,” Journal of the American Medical Association 143 (1950): 320–336; R. Doll and A. B. Hill, “Smoking and Carcinoma of the Lung: Preliminary Report,” British Medical Journal 2 (1950): 739–748. For a discussion of the significance of these articles, see Ernst L. Wynder, “Tobacco as a Cause of Lung Cancer: Some Reflections,” American Journal of Epidemiology 146 (9) (1997): 687–694, and Allan M. Brandt, “The Cigarette, Risk, and American Culture,” Daedalus 119 (4) (1990): 155–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.For examples of coverage in the popular press, see R. Norr, “Cancer by the Carton,” Reader’s Digest, December 1952, pp. 7–8; “Smoking & Cancer,” Time, July 5, 1952, p. 34; “Beyond Any Doubt,” Time, November 30, 1953, pp. 60–61; L. M. Miller and J. Monahan, “The Facts Behind the Cigarette Controversy,” Reader’s Digest, July 1954, pp. 1–6; “Smoke Gets in the News,” Life, December 21, 1953, pp. 20–21. See also Hans H. Toch, Terrence M. Allen, and William Lazer, “Effects of the Cancer Scares: The Residue of News Impact,” Journalism Quarterly 33 (1961): 25–34.

- 49.Wynder Ernst L., Evarts A. Graham, and Adele B. Croninger, “Experimental Production of Carcinoma With Cigarette Tar,” Cancer Research 13 (1953): 855–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edwin Dakin and Hill & Knowlton, “Forwarding Memorandum: To Members of the Planning Committee,” December 15, 1953, Trial Exhibit 8,904, available at http://tobaccodocuments.org/ness/3793.html; also available at Wisconsin Historical Society, John W. Hill Papers, Box 110, Folder 2, pp. 8–9.

- 51.See Cummings K. M., C. P. Morley, and A. Hyland, “Failed Promises of the Cigarette Industry and Its Effect on Consumer Misperceptions About the Health Risks of Smoking,” Tobacco Control 11 (Suppl 1) (2002): I110–I117, and R. W. Pollay, “Propaganda, Puffing and the Public Interest: Cigarette Publicity Tactics, Strategies and Effects,” Public Relations Review 16 (1990): 27–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liggett and Myers, “Fredric March Says—This Is It: ‘L&M Filters Are Just What the Doctor Ordered,’ ” February 22, 1954, Bates No. 2021368933, available at http://tobaccodocuments.org/pm/2021368933.html.

- 53.See Pollay R. W., “The Dark Side of Marketing Seemingly ‘Light’ Cigarettes: Successful Images and Failed Fact,” Tobacco Control 11 (Suppl 1) (2002): I18–I30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lorillard, “Have You Heard the Story of New Kent Cigarettes, Doctor?” 1953, Bates No. 92373155, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/eej54a00; Lorillard, “Why Is It, Doctor, That One Filter Gives So Much More Protection Than Any Other? Kent. The Only Cigarette With the Micronite Filter for the Greatest Protection in Cigarette History,” 1953, Bates No. 92373147, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mej54a00; Lorillard, “Have You Tried This Experiment, Doctor?” 1953, Bates No. 92373153, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gej54a00; Lorillard, “Some Questions About Filter Cigarettes That May Have Occurred to You, Doctor and Their Answers by the Makers of Kent,” August 22, 1953, Bates No. 89749655, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dnm13c00.

- 55.“Cigarette Hucksterism and the AMA,” Journal of the American Medical Association, April 3, 1954, p. 1180.13142896

- 56.Serpent on the Staff, 152–154.

- 57.“ ‘AMA Journal’ Stops Taking Cigaret Ads,” Advertising Age 1 (1953): 93. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Snegireff L. S. and O. M. Lombard, “Smoking Habits of Massachusetts Physicians: Five-Year Follow-Up Study (1954–1959),” New England Journal of Medicine 261 (1959): 603–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.For a discussion of a newsletter distributed across the country in doctors’ and dentists’ offices, see Hill & Knowlton, “I. Tobacco and Health—1962,” (November 15, 1961, Bates No. 966046705/6719, available at http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zgo21a00.

- 60.Serpent on the Staff, 155.