Abstract

Objectives. We examined the association between 2 important public health problems in the developing world: parental domestic violence and depressive symptoms during adolescence.

Methods. Data on depressive symptoms and witnessing of domestic violence were obtained during private face-to-face interviews conducted in 2002 with 2051 Filipino adolescents 17–19 years of age.

Results. Symptoms of depression were common; 11% of young men and 19% of young women reported wishing that they were dead occasionally or most of the time, and nearly half of all respondents recalled parental domestic violence. Female adolescents had significantly higher scores than male adolescents on a 12-item index of depressive symptoms. Both male and female adolescents who had witnessed parental domestic violence reported more depressive symptoms.

Conclusions. Filipino adolescents who have witnessed parental domestic violence are significantly more likely to report depressive symptoms.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), up to 20% of all children and adolescents suffer from a disabling mental illness.1 Globally, suicide is the third leading cause of death among adolescents.2 Although adolescent mental health issues have been relatively understudied, there is increasing evidence that a significant proportion of adolescents experience depression and that these symptoms can have lasting negative effects into adulthood. Worldwide, it is estimated that three quarters of childhood and adolescent mental disorders remain untreated, and in developing nations it is likely that 90% are not treated.3 Even in developed nations with “well-organized” health care systems, between 44% and 70% of such disorders remain untreated.3 In many lower income countries, there are fewer than 10 psychiatrists or psychologists per 1 million residents.4

Although overall rates of mental health disorders and behavioral disorders are similar among men and women, there are clear gender and age differences in depression.1 Depressive disorders are more common among women,5 whereas substance use and antisocial personality disorders are more common among men.4 Gender differences in levels of depression emerge during adolescence.6–8

In addition, the connections between domestic violence and mental health problems have been well documented in adult women.1,8–10 Several studies, mostly conducted in the United States, have shown that experiencing adverse events in childhood is associated with poorer mental health status in adulthood.11–15 Only limited data are available on depressive symptoms among adolescents and the relationship between such symptoms and parental domestic violence. We attempted to quantify levels of depressive symptoms in a cohort of more than 2000 Filipino adolescents and to assess the relationship of these symptoms to recall of parental domestic violence.

METHODS

We used data from the Cebu Longitudinal Health and Nutrition Survey, administered by the Office of Population Studies at the University of San Carlos in Cebu, the Philippines. All pregnant women in 33 randomly selected communities (barangays) in metropolitan Cebu were contacted, and 3327 women were included in the baseline survey in 1983. Follow-up surveys were conducted in 1984 to 1986, 1991, 1994, 1999, and 2002. In these follow-ups, data were also gathered on the women’s live-born, nontwin children (n=3080).16,17 We focused on data collected from 2051 adolescents (i.e., the sons and daughters of the original participants) during the 2002 survey, when these young men and women were aged 17 to 19 years. The surveys included modules on diet, education, health, and employment. The 2002 survey also included modules on mental health and domestic violence. All of the survey instruments were translated and back-translated from English into Cebuano, the local language in Cebu.

In assessing their mental health status, adolescents responded to a series of questions asking how often in the preceding 4 weeks they had experienced 12 common feelings or problems (Table 1 ▶). Ratings were made on a scale ranging from none of the time (1) to most of the time (3). We created a dichotomous variable for each of the 12 items (0= none of the time, 1=occasionally or most of the time). Also, we created an index of symptoms by summing scores on these variables. The index showed a high degree of reliability (Cronbach α =0.80). (When the analyses were conducted with indexes of symptoms that were both smaller and larger in size, the results were the same as with the 12-item index. The 12-item index had the highest degree of reliability in this sample.)

TABLE 1—

Measures of Depressive Symptoms Used

How frequently in the past 4 weeks did you experience these common feelings or problems?

|

Note. Response options were none of the time, occasionally, and most of the time.

The key independent variables were derived from a series of questions asked of adolescents regarding their recall of abuse committed by one of their parents against the other. Initially, adolescents were asked “Do you remember if either of your parents/caretakers ever hit, slapped, kicked, or used other means like pushing or shoving to try to hurt the other physically when you were growing up?” If they answered affirmatively, 2 follow-up questions were asked: “Who hurt the other physically?” (father, mother, both, or other) and “Do you ever recall one of your parents/caretakers needing medical attention as a result of being physically hurt by the other parent/caretaker?”

Statistical Analyses

Data were entered into dBASE and transferred to Stata (Stata Corp, College Station, Tex) for analysis. Initially, we assessed the overall prevalence of adolescents’ reports of domestic violence between their parents and their levels of depressive symptoms. We used cross-tabulations and χ2 analyses to explore the relationships between depressive symptoms and (1) the sociodemographic variables and (2) reports of domestic violence between parents. We used the overall index of depressive symptoms described earlier as the dependent variable in multiple linear regression analyses. Regression models assessed whether adolescents’ recall of domestic violence was significantly associated with their depressive symptoms after control for sociodemographic factors and stratification by gender.

RESULTS

The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are described in Table 2 ▶. There were no gender differences in age, urban residence, or household wealth; however, female adolescents had approximately 1 more year of schooling on average than male adolescents, and they were significantly more likely to report being married or cohabiting. Nearly half of the sample (48% of male respondents and 45% of female respondents) recalled witnessing parental domestic violence. Overall, 13% of adolescents remembered their mothers acting violently toward their fathers, 25.4% recalled their fathers hurting their mothers, and 7.3% reported witnessing mutual violence between their parents. Five percent of the respondents reported that 1 of their parents needed medical attention as a result of such an episode of physical violence. None of these prevalence levels significantly differed according to respondent gender.

TABLE 2—

Characteristics of the Sample of Adolescents: Cebu, the Philippines, 2002 (n = 2051)

| Male Adolescents | Female Adolescents | P | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age in 2002, y, mean (SD) | 18.2 (0.4) | 18.2 (0.4) | .48 |

| Urban residence, % | 74.4 | 73.9 | .86 |

| Last school grade completed (range: 1–15), mean (SD) | 9.7 (2.8) | 10.8 (2.2) | .0001 |

| Household wealth,a mean (SD) | 5.0 (2.5) | 5.0 (2.4) | .43 |

| Married or cohabiting, % | 4.0 | 14.2 | .0001 |

| Recall of parental domestic violence, % | |||

| Either parent hurt the other | 48.2 | 45.4 | .21 |

| Mother hurt father | 13.0 | 14.0 | .51 |

| Father hurt mother | 26.7 | 22.9 | .14 |

| Both hurt each other | 7.6 | 7.0 | .57 |

| Injury required medical attention | 5.5 | 5.2 | .75 |

| Depression index score, mean (SD) | 4.10 (2.8) | 5.04 (2.9) | .0001 |

aNumber of household items (range: 0–10).

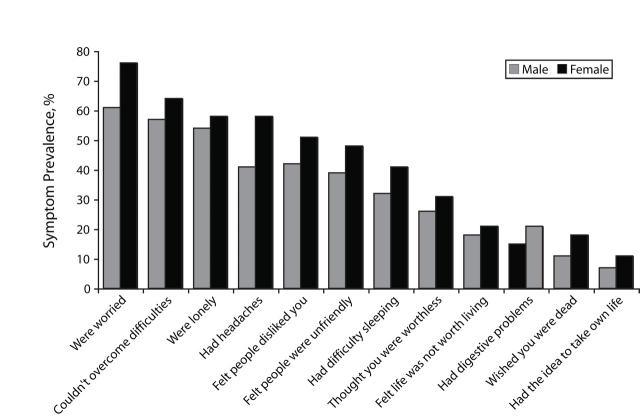

In contrast, there were significant gender differences in the levels of depressive symptoms reported. Female respondents had a significantly higher mean score (5.0) than male respondents (4.1) on the 12-item index of depressive symptoms (P<.0001). Figure 1 ▶ shows gender-specific levels of depressive symptoms. All of the gender differences depicted were significant at the .05 level with the exceptions of loneliness (P=.06) and thinking that life is not worth living (P=.09).

FIGURE 1—

Percentages of adolescents reporting symptoms of depression occasionally or most of the time during the previous 4 weeks, by gender.

Three quarters of young women and 61% of young men reported worrying occasionally or most of the time during the preceding 4 weeks, and more than half of the female respondents felt lonely, could not overcome difficulties, had headaches, felt disliked, and reported difficulty sleeping. A quarter of the male respondents reported feeling they were worthless occasionally or most of the time during the preceding 4 weeks, almost a fifth thought life was not worth living, 11% wished they were dead, and 7% thought about taking their own life. Thirty-one percent of young women thought they were worthless, 21% thought life was not worth living, 19% wished they were dead, and 11% thought about taking their own lives.

Table 3 ▶ shows relationships, stratified by gender, between adolescents’ scores on the depressive symptoms index and their recall of parental domestic violence. Each of the 5 statistical models depicted addressed 1 type of parental domestic violence and adjusted for the factors shown in Table 2 ▶. We adjusted the models for community effects by clustering according to community. Male respondents who recalled either parent hurting the other had average depressive symptom scores that were 0.78 points higher than the scores of those who did not recall violence between their parents. Male respondents who recalled their fathers hurting their mothers had average scores 0.61 points higher than the scores of those who did not recall this type of violence, and young men who remembered both parents hurting each other had average scores that were 1.18 points higher than those of young men who did not recall mutual violence between their parents.

TABLE 3—

Linear Regression of Depressive Symptoms Index on Recall of Domestic Violence, by Gender

| Male Adolescents | Female Adolescents | |||

| Model | Adjusted b (95% CI) | P | Adjusted b (95% CI) | P |

| Model 1: either parent hurt the other | 0.78 (0.41, 1.15) | .0001 | 0.94 (0.55, 1.33) | .0001 |

| Model 2: mother hurt father | −0.14 (−0.62, 0.33) | .55 | 0.62 (0.06, 1.08) | .03 |

| Model 3: father hurt mother | 0.61 (0.18, 1.03) | .005 | 0.56 (0.17, 0.94) | .005 |

| Model 4: both hurt each other | 1.18 (0.56, 1.79) | .0001 | 0.76 (−0.13, 1.56) | .06 |

| Model 5: injury required medical attention | 0.52 (−0.26, 1.30) | .19 | 2.10 (1.35, 2.85) | .0001 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; b = unstandardized β coefficient. Each model controlled for age in 2002, urban residence, last school grade completed, socioeconomic status, and marital status. All standard errors were corrected for clustering at the community level. Significance values for differences by gender (interactions) were .07 for model 2 and .01 for model 5.

The results were similar for female respondents in terms of the magnitudes and significance levels of the coefficients for either parent hurting the other and for fathers hurting mothers (P s<.005). The difference for parents mutually committing domestic violence failed to reach statistical significance (P=.06), whereas young women who recalled their mother hurting their father had average depressive symptoms index scores that were 0.63 points higher than those of young women who had not witnessed this type of violence. Female respondents who recalled that 1 of their parents required medical attention as a result of domestic violence had average depressive symptom scores that were 2.1 points higher than the scores of those not reporting instances in which one of their parents needed medical attention.

DISCUSSION

We found that depressive symptoms were common among Filipino adolescents aged 17 to 19 years, and a substantial proportion of these young people reported serious symptoms. Female respondents exhibited significantly higher rates than male respondents for nearly all of the depressive symptoms assessed. Eighteen percent of young men and 21% of young women, respectively, reported feeling that life was not worth living, and 7% and 11%, respectively, reported that they had thought of taking their own lives. These findings are in line with the 2002 Young Adult Fertility and Sexuality Survey, which showed that 6% of young men and 16% of young women 15 to 19 years of age had thought about suicide and that 22% of those who had considered suicide had attempted it.18

This study addressed key issues on the frontier of domestic violence research, that is, the mutuality of domestic violence between partners19 and the intergenerational impact of violence.20 Among both male and female respondents, recall of any parental domestic violence was strongly associated with increased frequencies of depressive symptoms. However, we found gender differences in linkages. Young women reported more depressive symptoms across all of the different types of parental domestic violence, whereas young men did not report more depressive symptoms for when their mothers hurt their fathers or when 1 parent needed medical attention than for other domestic violence situations.

Finally, the data set did not include measures of child abuse, which might be a link in explaining the association between witnessing parental domestic violence and experiencing depressive symptoms.

At present, only 0.02% of the health budget in the Philippines is allocated to mental health; there are 0.4 psychiatrists per 10000 people, and there is no system allowing collection of data on mental health.4 Evidence suggests that treatment of depression is cost-effective in developing nations21; however, in many such countries, including the Philippines, it is not feasible to provide treatment through the medical systems currently in place. Perhaps innovative approaches such as focusing on social support to prevent depression and enhance the skills of nonmedical providers—strategies that have been effective in some developing countries22—should be pursued.

In addition to these financial and health care system limitations in treatment and prevention, too few researchers are investigating adolescent mental health in the developing world, and this has been a major concern of WHO. As a means of furthering the dissemination of mental health research, WHO convened a meeting in 2003, “Mental Health Research in Developing Countries: Role of Scientific Journals.” As a result of this meeting, WHO and attending journal editors issued a statement that highlighted the need for local capacity building for researchers in developing countries to publish studies focusing on mental health. Given that there are more than 1.2 billion adolescents worldwide and that 4 of every 5 live in developing nations, public health researchers need to collect longitudinal data on and conduct cost-effectiveness analyses of treatment of mental health problems in adolescence.23 Poor adolescent mental health should be considered a potential consequence of domestic violence as well as other types of violence.

Our study is among the first conducted in the developing world that has explored adolescent mental health and its association with witnessing domestic violence. Both mental health and domestic violence have been of increasing concern in the public health community, and the data presented here suggest that interventions designed to reduce domestic violence may also help prevent the development or decrease the severity of depressive symptoms among adolescents. If they are not treated, adolescents with depression are at risk for continued mental health problems that can persist and lead to future morbidity, loss of productivity, and mortality. Population- and community-based efforts that include destigmatization of common depressive symptoms are needed in addition to individual-level treatment strategies for more serious symptoms of depression.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant HD042540) and Fogarty International (grant TW005596).

Michelle J. Hindin is grateful to the fieldwork team at the Office of Population Studies, Cebu, the Philippines, for collecting the data and continuing to follow the Cebu Longitudinal Health and Nutrition Survey cohort.

Human Participant Protection All rounds of the survey were approved by the institutional review board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and the 2002 survey also was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Informed consent was obtained from all adult participants, and consent from a parent or guardian was obtained for unmarried adolescents (younger than 18 years).

Peer Reviewed

Contributors M. J. Hindin conceptualized the article and led the writing and analyses. S. Gultiano assisted in the design of the instruments and supervised the data collection. Both authors interpreted findings and reviewed drafts of the article.

References

- 1.World Health Report 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

- 2.Caring for Children and Adolescents With Mental Disorders: Setting WHO Directions. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003.

- 3.Investing in Mental Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003.

- 4.Atlas: Mental Health Resources in the World, 2001. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

- 5.Astbury J, Cabral M. Women’s Mental Health: An Evidence Based Review. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000.

- 6.Gold JH. Gender differences in psychiatric illness and treatments: a critical review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186:769–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wade TJ, Cairney J, Pevalin DJ. Emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence: national panel results from three countries. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychol Bull. 1994;115:424–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:128–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bensley L, Van Eenwyk J, Wynkoop SK. Childhood family violence history and women’s risk for intimate partner violence and poor health. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25:38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord. 2004;82:217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gladstone GL, Parker GB, Mitchell PB, Malhi GS, Wilhelm K, Austin MP. Implications of childhood trauma for depressed women: an analysis of pathways from childhood sexual abuse to deliberate self-harm and revictimization. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1417–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA. 2001;286:3089–3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Giles WH, Anda RF. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1900. Prev Med. 2003;37:268–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Gould MS, Kasen S, Brown J, Brook JS. Childhood adversities, interpersonal difficulties, and risk for suicide attempts during late adolescence and early adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002; 59:741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cebu Longitudinal Health and Nutrition Survey: survey procedures. Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/cebu/docs/clhn1.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2006.

- 17.Cebu Study Team. Underlying and proximate determinants of child health: the Cebu Longitudinal Health and Nutrition Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:185–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cruz GT, Berja CL. Nonsexual risk behaviors. In: Raymundo CM, Cruz GT, eds. Youth Sex and Risk Behaviors in the Philippines. Quezon City, the Philippines: Demographic Research and Development Foundation Inc; 2004:50–69.

- 19.Langhinrichsen-Rohling J. Top 10 greatest “hits”: important findings and future directions for intimate partner violence research. J Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin SL, Moracco KE, Garro J, et al. Domestic violence across generations: findings from northern India. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:560–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chisholm D, Sanderson K, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Saxena S. Reducing the global burden of depression: population-level analysis of intervention cost-effectiveness in 14 world regions. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenzie K, Patel V, Araya R. Learning from low income countries: mental health. BMJ. 2004;329:1138–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adolescence: A Time That Matters. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2002.