Abstract

The reliance on discretionary spending for American Indian/ Alaska Native health care has produced a system that is insufficient and unreliable and is associated with ongoing health disparities. Moreover, the gap between mandatory spending on a Medicare beneficiary and discretionary spending on an American Indian/Alaska Native beneficiary has grown dramatically, thus compounding the problem.

The budget classification for American Indian/Alaska Native health services should be changed, and health care delivery to this population should be designated as mandatory spending. If a correct structure is in place, mandatory spending is more likely to provide adequate funding that keeps pace with changes in costs and need.

And that has made all the difference.

—Robert Frost1

THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT has made many promises to American Indians and Alaska Natives to provide for their health care needs. Treaties, court cases, and a good deal of rhetoric all describe a trust relationship between the United States and tribes. Reality reveals another relationship: American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) health care is consistently funded at a dramatically lower level than other government health programs. Shortages, backlogs, and deficiencies in AIAN health services, although harder to quantify and compare, also exist.2 Concurrently, American Indians and Alaska Natives have considerably worse health outcomes—including higher infant mortality rates, more disease and disability, and shorter life expectancies—than much of the rest of America.3–5 It is likely that these outcomes are related to the inadequate funding of AIAN health programs.

The AIAN health care system can be improved through various reforms.2 Consideration should be given to strengthening the Indian Health Service (IHS), improving options for tribal management of services, expanding services to urban Indians, increasing Medicaid and Medicare eligibility and services for American Indians and Alaska Natives, and creating universal health insurance that comprehensively reaches this population along with other Americans.

However, it is not the purpose of this article to wrestle with these delivery system options. Rather, we describe a single problem common to all reform proposals and to all current AIAN health systems—whether IHS-administered, tribally administered, or urban Indian health programs (commonly referred to collectively as “I/T/U”)—and then propose a multipart remedy. This problem is how AIAN health spending is classified and processed in the federal budget.

In current federal legislation, the vast majority of AIAN spending is treated as “discretionary.” In contrast, Medicare and Medic-aid are classified as “mandatory.” The reliance on discretionary spending for AIAN health care has produced a system that is insufficient and unreliable and that is associated with ongoing health disparities. Moreover, as demonstrated subsequently, the gap between mandatory spending on a Medicare beneficiary and discretionary spending on an AIAN beneficiary has grown 8-fold over the past 20 years, compounding the problem.

The budget classification for AIAN health services should be changed: AIAN health care delivery should be designated as mandatory spending. If the correct structure is in place, mandatory spending is more likely to provide adequate funding levels that keep pace with changes in costs and need. However, this reclassification, although necessary, will not in itself be sufficient to address all AIAN health care delivery problems. There are many systemic issues to review and consider. But different budget treatment is crucial for the success of any new approach. The promises of AIAN health care are an American moral obligation and a federal legal duty. They should be clearly honored for the future, not subordinated to annual funding fights.

BACKGROUND

Promises of Federal AIAN Health Legislation

The complex history of federal support for AIAN health services dates long before the concepts of discretionary and mandatory spending arose and diverged.6,7 As presidential executive orders have explicitly acknowledged, “[t]he United States has a unique legal relationship with Indian tribal governments as set forth in the Constitution of the United States, treaties, statutes, Executive orders, and court decisions.”8,9

As part of this relationship, the US government bears a federal trust responsibility to tribes that the Supreme Court has analogized to the duties of a guardian to its wards.10 This doctrine is “an established legal obligation which requires the United States … to provide economic and social programs necessary to raise the standard of living and social well-being of the Indian people to a level comparable to the non-Indian society.”11

Treaty language and statutes have placed health care services within the promised social programs of the trust responsibility. Multiple treaties promised physicians and medical supplies to tribes.12–15 As noted by Dixon and Roubideaux, “Tribes paid for their health care by relinquishing their land to the federal government in the past for the promise of health care in the future.”5(pxix) In health policy jargon, others have said that American Indi-ans and Alaska Natives purchased the first prepaid health plan in history.16

For most purposes, this trust responsibility for health care is now represented by the Snyder Act of 1921 (as amended)17 and the Indian Health Care Improvement Act (IHCIA) of 1976 (as amended).18 The Snyder Act provides for “the relief of distress and conservation of health [and] for the employment of … physicians … for Indian tribes.”17 The IHCIA is more explicit:

Federal health services to maintain and improve the health of the Indians are consonant with and required by the Federal Government’s historical and unique legal relationship with, and resulting responsibility to, the American Indian people… .18 [I]t is the policy of this Nation, in fulfillment of its special responsibilities and legal obligation to the American Indian people, to assure the highest possible health status for Indians and urban Indians and to provide all resources necessary to effect that policy.19 [italics added]

Funding for AIAN clinical health services under these (and other smaller) acts totaled just over $2 billion in fiscal year 2004. (In addition to these specific AIAN programs, if individual American Indians and Alaska Natives meet certain criteria, they may also be eligible for Medicaid and Medicare. It has been estimated that 25% of spending on AIAN health care is derived from these and other third-party sources.20)

Federal Budgeting

The Congressional Budget Act of 197421,22 is the superstructure that governs the process by which all federal financial decisions are made. Although it was enacted only 30 years ago, all preexisting programs (such as the Snyder Act) have been retrofitted to its design, and all subsequently enacted programs must conform to it. Under the Budget Act, there are 2 types of funding: discretionary spending and mandatory spending. They are treated differently in almost all respects, and they generally cannot be transmuted from one into the other.

Discretionary spending.

As the label implies, discretionary spending refers to money provided at the discretion of Congress and the president. Most federal grants and contracts—whether for health, defense, foreign aid, or highways—fall under this category. Discretionary spending usually takes the 2-step form of authorizations and appropriations. Authorizations are, in general, the multiyear statutory framework of a program and the legal permission for the program to receive appropriations. (The Snyder Act and the IHCIA are authorizations.) Appropriations are, in general, annual laws that provide the actual funding for the coming year. Such actual funding may range anywhere from none of the authorized amount to the entire authorized amount.

Every year, advocates for a program funded with discretionary spending must seek a new appropriation for the program to continue. If Congress in any given year chooses not to provide funds, there are no legal or procedural consequences. The program simply ceases to operate. Over time, appropriations may fall, stay steady, or rise according to each year’s political decisions. Less obviously, but commonly, appropriations may actually rise year after year but nonetheless fall further and further behind the true need for spending. Consider a discretionary grant program providing drugs for uninsured people; if the price of drugs grows faster than the available discretionary funds, a progressively smaller proportion of those in need can be assisted, and “[w]hen allotted funds are spent … the services cease to be provided.”23(p105)

Mandatory spending.

By contrast, mandatory spending refers to funds guaranteed in advance of annual appropriations; it is a promise in law that the money will be there when needed. (A subset of mandatory spending is referred to as “entitlements spending,” usually describing funds spent for benefits targeted toward individuals.24) The legal consequences for a failure by Congress to provide mandatory funding may vary; in many instances, private rights of action to enforce the law are available.25 However, regardless of how the guarantee can be enforced, the presumption is that necessary money will be available unless Congress changes the underlying law.

Mandatory spending can exist in both open-ended and capped forms. Medicaid and Medicare are open-ended; whatever the cost of statutory guarantees, the federal government will provide funds. By contrast, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program has explicit dollar maximums; funding up to the maximum level will be provided, but beyond that the guarantee of funding explicitly ceases.

Unlike discretionary spending, growth in mandatory spending occurs without further congressional action. In mandatory spending for Social Security, a cost of living adjustment is an automatic and permanent way of preserving the value of the benefits promised.26 Likewise, in Medicare and Medicaid, because the law promises that certain goods and services will be provided to eligible individuals, open-ended mandatory spending grows automatically to meet the costs.

This automatic growth is not simple arithmetic. For a variety of reasons, providing the identical amount of money from one year to the next will probably be inadequate to keep the promise of a health care program. The most obvious reason for change over time is inflation. Another is the increase in the number of beneficiaries; for example, as the “baby boom” generation ages, more people are eligible for Medicare. Yet another reason for the need for additional money is the advent of new, more expensive technologies in the mix of covered goods and services (such as the move from x-rays to computerized axial tomography scans).

Thus, to keep the statutory promises in Medicare and Medicaid to pay for health services, mandatory spending must grow to reflect, at a minimum, the amount of money spent in the previous year plus inflation plus costs associated with increases in beneficiaries plus costs associated with new technologies, including drugs. A program’s failure to grow by this amount would erode the purchasing power of the program and incrementally break the underlying legal promises.

PROMISES AND BUDGETING

Since the creation of the Congressional Budget Act, AIAN health care programs have fallen under the category of discretionary spending. As a consequence, the promises made to American Indians and Alaska Natives through the Constitution, statutes, case law, and treaties have been subject to the annual willingness of Congress and the president to provide sufficient funds. Whether the authorization pledges to provide a physician, to “permit the health status of Indians to be raised to the highest possible level,”27 or to raise “the status of health care for American Indians and Alaska Natives … to a level equal to that enjoyed by other American citizens,”18 the promise is a hollow one unless annual funding follows.

This obviously stands in direct opposition to the doctrine of the federal trust relationship. Congress can erode or even break the government’s promises to provide health care simply by withholding funds. In the 1950s, Congress overtly terminated the federal status of 109 tribes, ending tribal sovereignty, selling tribal lands, and cutting off American Indians from vital programs.28 As long as AIAN health program funding is treated as discretionary, Congress likewise retains the power of “incremental termination” of promised health benefits by withholding sufficient funding for services.

This has, to some degree, already occurred. Evidence can be found in the work of the Level of Need Funded Workgroup (LNF) of the IHS (now known as the Federal Employees Health Plan [FEHP] Disparity Index Work-group). In 1999, the LNF developed a sophisticated actuarial model comparing available appropriations per person for AIAN medical services (whether administered by the IHS or by tribes) with the amount needed to purchase a benefits package comparable to that provided through the FEHP. The researchers concluded that the IHS was funded at a level of only 54% of what was needed.29 Ongoing work by the IHS to develop a methodology for distribution of special supplemental funds continues to identify similar short-changing, including some units that receive less than 40% of what is needed to provide a package comparable to the FEHP.30

This comparison is admittedly inexact. Although the FEHP premium is probably a good benchmark for “average price for average coverage,” federal employees and American Indians and Alaska Natives will inevitably differ in terms of age, disability status, area of residence, service needs, and other sources of payment. The LNF model attempted to estimate and correct for such issues, but accurate data are difficult to come by.29 Comparisons between AIAN spending and Medicare and Medicaid, subject to still more qualifications than the comparison with the FEHP, are even more dramatic.2(p44)

Nonetheless, the LNF model and other comparisons do illustrate a very basic truth. Whatever the adjustments and uncertainties of per person estimates and costs may be, the system of health care delivery for American Indians and Alaska Natives has been funded at levels dramatically lower than those of other government health programs.

Indeed, the congressional act that resulted in the use of the FEHP Disparity Index methodology itself clearly illustrates the fundamental unreliability of discretionary spending to meet the goals of authorized programs. The statute calls on the secretary of health and human services to use new, supplemental funds for the purpose of “eliminating the deficiencies in health status and resources of all Indian tribes [and] eliminating backlogs in the provision of health care services to Indians.”31 This is a laudable goal. However, the 2003 appropriation provided by Congress to reach this goal was $23 million, whereas the estimated cost of meeting the need was $1.8 billion.32 Recent estimates by IHS officials note a shortfall of $2 billion.33

Equally troubling is the fact that this problem is compounded year after year. Not only is the base amount of per capita spending for AIAN health programs far smaller than that for other programs, this spending grows at a slower rate, losing comparatively more ground over time.23(p107)

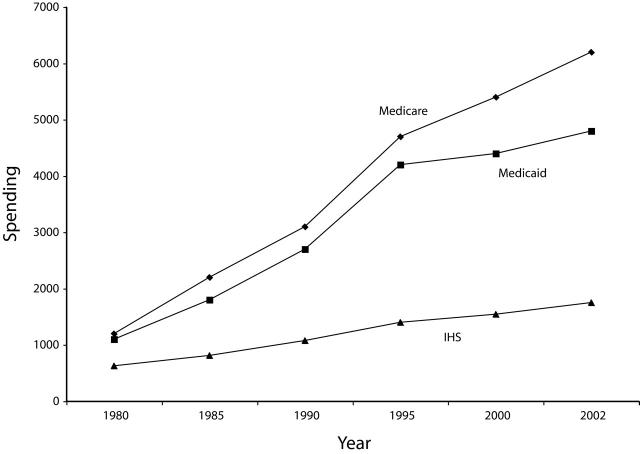

Figure 1 ▶ depicts growth in expenditures per capita for Medicare, Medicaid, and the IHS. Between 1980 and 2002, Medicare per capita spending grew at an average of 7.8% per year; Medicaid, at 6.9% per year; and IHS, at only 4.8% per year. In other words, during the period in which Medicare spending per person grew by $5200, IHS per person appropriations grew by only $1121. Had IHS per capita appropriations grown at the Medicare rate during this period, IHS per capita spending would have been almost double ($3260 per capita rather than $1752).

FIGURE 1—

Per capita spending, by Medicare, Medicaid, and the Indian Health Service (IHS), 1980–2002.

Note. Medicare and Medicaid data were obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services37 (using “enrollee” estimates). IHS user data were obtained from annual unpublished IHS memoranda (1989–2002); extrapolations for years in which IHS data were unavailable were made via fitting a straight line to available data points. IHS appropriations data were derived from (1) the US Department of Health and Human Services38 and (2) written and oral communications with IHS and Department of Health and Human Services program officials in August 2004.

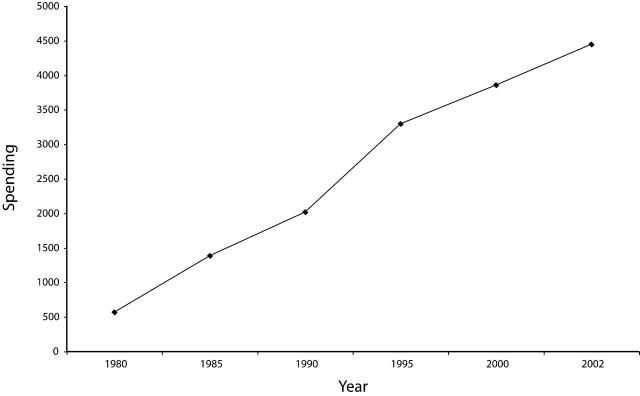

As can be seen in Figure 2 ▶, on an average annual basis from 1980 to 2002, the gap between IHS per capita spending and Medicare per capita spending grew at about 10% every year. In dollars per capita, the gap between these government programs grew from $569 to $4448. In 1980, the gap was 90% the size of IHS per capita spending; by 2002, the gap alone was 250% of IHS per capita spending. Any pretense that the 2 programs can purchase an adequate package of health services becomes less credible as time proceeds. Even as appropriations for the IHS increase, they fall further and further behind a Medicare benchmark on a per capita basis.

FIGURE 2—

Gaps in per capita spending between the Indian Health Service (IHS) and Medicare, 1980–2002.

Note. Medicare and Medicaid data were obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services37 (using “enrollee” estimates). IHS user data were obtained from annual unpublished IHS memoranda (1989–2002); extrapolations for years in which IHS data were unavailable were made via fitting a straight line to available data points. IHS appropriations data were derived from (1) the US Department of Health and Human Services38 and (2) written and oral communications with IHS and Department of Health and Human Services program officials in August 2004.

Especially notable is that, although many specific statutory changes altered spending up and down during the 1980 to 2002 period, most Medicare spending grew automatically as a consequence of the program’s mandatory spending mechanisms.34 By contrast, AIAN health service funding grew with uncertainty and without relationship to the level of services needed by AIAN beneficiaries. Whereas Medicare and Medicaid increased automatically as a result of inflation, increased numbers of beneficiaries, and changes in the service mix, supporters of AIAN health services had to seek the funds for these additional costs in appropriations each year, making it a struggle for programs even to stay at their already inadequate levels. (Making it explicit what a struggle this is, Dixon and Roubideaux dedicated their book to the “warriors of today … who travel to the halls of Congress to battle for better health care.”5(pv))

These funding shortfalls are not simply abstractions. Again, others have written well about the significant disparities in AIAN health outcome measures and about the systemic shortages and rationing in services to this group, and we need not revisit those issues in detail here.5 It is likely that these problems are correlated with the health care funding available to American Indians and Alaska Natives, funding that started at a lower level than other programs and that has lagged behind more and more over time.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Regardless of the design of the finance and delivery system advocated, every proposal for improving AIAN health must address the budget treatment of its funding. Three steps should be pursued, either simultaneously or in sequence. Pursued legislatively, each of them would require amendments to the basic AIAN health authorizations and, perhaps, to the Congressional Budget Act itself. Although relatively simple to describe, these proposals involve complex budget and health services calculations to carry out, with many intervening questions (e.g., the manner in which urban Indians are included in the calculations). As with all issues associated with AIAN health, tribes should be consulted in carrying out these steps and answering these questions.

Step 1: Treat AIAN Health Funding as Mandatory Spending

The first step is to change the classification of existing AIAN health service budgets to the mandatory spending category. Even if future activity is as basic as a reauthorization of the IHCIA at current levels, a move to guarantee funding is worthwhile. It would provide certainty of ongoing funding without reduction or interruption, and at the same time it would relieve the burden of annual advocacy.

Step 2: Automatically Adjust AIAN Health Funding to Preserve Purchasing Power

Budget reclassification alone, however, is not sufficient because increases in costs over time will immediately erode the value of a fixed amount. As a second step, redesignation should be accompanied by a form of automatic annual adjustment keyed to increased costs and the number of eligible people. Without such an automatic increase, funding will become stagnant as purchasing power declines.

For the reasons noted earlier and outlined in the LNF model, the cost of care for American Indians and Alaska Natives may be different from that for the general US population. The development of an AIAN-specific cost-of-care index would require dramatically improved data and a period for study, review, and consultation. This does not mean, however, that the adjustment should be postponed. Rather, the legal change should include, as an interim proxy measure, an inflator mirroring the change in Medicare or Medicaid spending per person, with the expectation that a more direct inflator will be substituted when it is developed. With such an adjustment, AIAN health funding could retain its purchasing power over time.

Step 3: Make AIAN Health Funding Rates Comparable to Other Government Programs

Steps 1 and 2 are not enough in themselves, because they provide guaranteed, adjusted funding only at a base level already known to be seriously insufficient. The third step in this simple but ambitious course would be to increase the per person funding available under this new mandatory spending program to a level comparable to that under other federal health programs, adjusted for differences in health status and services. Again, for the reasons mentioned earlier, AIAN per capita spending will almost certainly be very different from that for the average elderly or disabled Medicare beneficiary, and improved data will be required in this area. But an interim measure should be adopted for use now, while the specifics of the AIAN per capita rate are developed. The blunt truth is that even the most limited of these other programs’ current per person amounts are far, far above what the AIAN health service programs now receive.

CAUTIONARY CONCLUSION

Given the current debates about budgets and deficits, these 3 steps toward mandatory spending for AIAN health will be a difficult political struggle. Congress has recently discussed entitlement caps, Medicaid block grants, and privatization of Social Security. Even the 2003 Medicare prescription drug law encountered serious opposition because of concerns about the federal deficit.35,36 It is unlikely that legislators will readily agree to transform and increase spending for AIAN programs.

In contrast to the Medicare prescription drug debate, however, these political opponents are caught on the horns of a dilemma if they oppose budget parity for AIAN programs. Creating the Medicare prescription drug benefit involved making a new promise. Making AIAN spending mandatory, automatically adjusted, and comparable is, in fact, simply keeping age-old promises. As noted earlier, treaties, statutes, and US Supreme Court decisions emphasize the ongoing responsibility of the federal government for the well-being of American Indians and Alaska Natives.

This suggested updating of these legal pledges puts the federal budget where the federal promise is. It is worth doing. Some will oppose this action to provide for the health care needs of American Indians and Alaska Natives. But the debate will require them to say out loud that they are prepared to break the federal promise rather than allowing them to leave it quietly unfulfilled and increasingly hollowed out.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by an Investigator Award in Health Policy Research from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

We would like to thank Ellen O’Brien for her advice and counsel and Theresa Jordan, Nick Olcott, and Malini Sangha for their assistance in the preparation of this article.

Note. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors T.M. Westmoreland was the principal author of the article. K. R. Watson authored the section on federal Indian law and assisted in revising the article.

References

- 1.Frost R. The road not taken. Available at: http://www.poets.org/poems/poems.cfm?prmID=1645. Accessed January 12, 2005.

- 2.Dixon M, Roubideaux Y, eds. Promises to Keep: Public Health Policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2002.

- 3.Berry MF, Reynoso C, Braceras JC, et al. A quiet crisis: federal funding and unmet needs in Indian country. Available at: http://www.usccr.gov/pubs/na0703/na0731.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2005.

- 4.Zuckerman S, Haley J, Roubideaux Y, Lillie-Blanton M. Health service access, use, and insurance coverage among American Indians/Alaska Natives and whites: what role does the Indian Health Service play? Am J Public Health. 2004; 94:53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuckerman S, Haley J, Roubideaux Y, Lillie-Blanton M. American Indians and Alaska Natives: Health Coverage and Access to Care. Menlo Park, Calif: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2004. Fact sheet 7020.

- 6.Shelton BL. Legal and Historical Roots of Health Care for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States. Menlo Park, Calif: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2004.

- 7.Kunitz S. The history and politics of US health care policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1464–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Executive Order No. 13084, 63 Federal Register 27655 (1998).

- 9.Executive Order No. 13175, 65 Federal Register 67249–67252 (2000).

- 10.Cherokee Nation v Georgia, 30 US 1, 17 (1831).

- 11.American Indian Policy Review Commission. Final Report, U.S. Senate Select Commission on Indian Affairs, 95th Congress, Meetings of the American Indian Policy Review Commission. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1978. Cited by: Kickingbird K. The sacred and the profane: Second Annual Academic Symposium in Honor of the First Americans and Indigenous Peoples Around the World. St. Thomas Law Rev. 1996;9: [Google Scholar]

- 12.Treaty with the Kiowa and Comanche, Article 14, 15 Stat 581 (1867).

- 13.Treaty with the Crows, Article 10, 15 Stat 649 (1868).

- 14.Treaty with the Eastern Band Shoshoni, Article 10, 15 Stat 673 (1868).

- 15.Treaty with the Northern Cheyenne, Article 13, 15 Stat 655 (1868).

- 16.Oversight hearing on the president’s proposed Indian Health Service budget for fiscal year 1997 (statement of Daniel K. Inouye). Available at: http://www.ihs.gov/PublicAffairs/Bios/PreviousDirectors/Trujillo_Stmts_Initiatives/1997_Senora.cfm. Accessed January 12, 2005.

- 17.Snyder Act of 1921 ch.115, 42 Stat 208, 25 USC §13 (1921).

- 18.Pub L No. 94–437, 90 Stat 1400, 25 USC §1601, et seq.

- 19.Indian Health Care Improvement Act, 25 USC §1602(a) (2000).

- 20.Level of Need Funded Workgroup. Draft final report (part two): Level of Need Funded Cost Model—Indian Health Service. Available at: http://www.ihs.gov/NonMedicalPrograms/Lnf/dld_files%5CP2SumD.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2005.

- 21.Pub L No. 93–344, 88 Stat 297.

- 22.Congressional Budget Act, 2 USC §601 (1974).

- 23.Dixon M, Mather D, Shelton B, Roubideaux Y. Organizational and economic changes in Indian health care system. In: Dixon M, Roubideaux Y, eds. Promises to Keep: Public Health Policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2002:105.

- 24.Office of Management and Budget. Glossary. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/fy2004/glossary.html. Accessed January 12, 2005.

- 25.Jost T. Disentitlement? The Threats Facing Our Public Health-Care Programs and a Rights-Based Response. New York, NY: Oxford University Press Inc; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Social Security Administration. Brief history of Social Security. Available at: http://www.ssa.gov/history/reports/briefhistory.html. Accessed January 12, 2005.

- 27.Indian Health Care Improvement Act, 25 USC §1601(b) (2000).

- 28.Cohen FS. Handbook of Federal Indian Law. Buffalo, NY: William S Hein & Co; 1982.

- 29.Level of Need Funded Workgroup. Final report: Level of Need Funded Cost Model—Indian Health Service. Available at: http://www.ihs.gov/NonMedicalPrograms/Lnf/Dld_files/p1sum.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2005.

- 30.Indian Health Service. FY 2003 Indian Health Care Improvement Fund—area summary. Available at: http://www.ihs.gov/NonMedicalPrograms/Lnf/2003/AreaAllowanceSummary.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2005.

- 31.Indian Health Care Improvement Act, 25 USC §1621 (2000).

- 32.Indian Health Service. FDI FEHP Disparity Index. Available at: http://www.ihs.gov/NonMedicalPrograms/Lnf/. Accessed January 12, 2005.

- 33.Stark M. Tribal conference: Indian health funds short. Billings Gazette [serial online]. Available at: http://www.billingsgazette.com/index.php?id=1&display=rednews/2004/08/25/build/local/30-tribal-conference.inc. Accessed January 12, 2005.

- 34.Congressional Budget Office. Long-term budgetary pressures and policy options. Available at: http://www.cbo.gov/showdoc.cfm?index=492&sequence=5. Accessed January 12, 2005.

- 35.Brownstein R. Snowballing debt awaits tomorrow’s taxpayers. Los Angeles Times. December 1, 2003:A11.

- 36.Pub L No. 108–173, 117 Stat 2066.

- 37.Program Benefit Payments per Enrollee, Selected Fiscal Years. Baltimore, Md: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary; 2003.

- 38.Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees, FY 2003. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2003.