Those who review the vast historical archive of the AIDS epidemic will find there a wealth of visual images that testify to the events, messages, meanings, strategies, and emotions of the past 25 years. In some remarkable cases, these images, with a little effort on the part of the viewer, are able to produce analyses and suggest actions in response to the epidemic that are no less relevant now than they were at the time of their creation. This is the case with the image on the cover of this month’s issue of the American Journal of Public Health.

The SILENCE=DEATH logo was produced in 1987 by the SILENCE=DEATH project design collective, which lent the image to the newly formed activist group, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). This self-described, “nonpartisan group of diverse individuals united in anger and committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis,”1(p7) used the image as a form of cultural activism and placed the logo on many of the group’s carefully crafted images, slogans, logos, street protests, chants, and media analysis and production projects.1 Through ACT UP’s sophisticated use of image, language, and performance, the group advanced new analyses of the epidemic and attracted the attention of the mainstream media that had, up until that point, focused most of its attention on images of persons suffering with AIDS or on sensationalized accounts of transmission routes and events.

In 1988, ACT UP members formed the arts collective Gran Fury, which was dedicated “to exploiting the power of art to end the AIDS crisis,”2(p227) and, in the span of just a few years, produced work that advanced the view that the AIDS epidemic, like all epidemics, is a social crisis that requires a far richer repertoire of interventions than is possible with exclusively biomedical and public health approaches.2 This cultural analysis and activism transformed public health and inspired new forms of social activism, as is evident in the employment of ACT UP–like tactics (such as capturing the attention of the mainstream media and shaping the messages the media report and developing the scientific knowledge necessary to have “lay experts” influence research and treatment agendas and policies) in many of the health-related social movements of the past 2 decades. The work of Gran Fury also renewed efforts to employ art as a mechanism for social change.

The simplicity of the SILENCE= DEATH logo belies the complexity of its provocation. The stark equivalency is amplified by its design, particularly the contrast between the bold white capital letters and the deep black background. The “=” sign is both mathematical and metaphoric and may be read as a question, proposition, challenge, or assertion, each with the capacity to support multiple interpretations. For example, the sign’s logic may be applied to state-level failures to address the epidemic adequately as well as to silence of individuals who deny that they are implicated in the epidemic. The logo may also be read as a call to those living with AIDS to announce their status and mobilize in solidarity with others. That is, the statement not only represents aspects of the crisis, it is also a statement of analysis and provokes actions aimed at changing the conditions of the crisis.

The pink triangle is an intrinsic part of the image and adds a critical historical dimension that underscores the urgency of the slogan. The Nazi regime required homosexuals to wear pink triangles, a visual marker equivalent to the Star of David worn by Jews. Thousands of homosexuals were interned in concentration camps during this period and were exterminated along with Jews, Gypsies, and others. In the 1960s, gay activists claimed the pink triangle as the emblem of the struggle for sexual rights, and its inclusion in the SILENCE=DEATH image creates continuity between that movement and ACT UP’s mobilization against AIDS. The inclusion of the pink triangle also advances the position that the failure to act to end the epidemic, particularly on the part of state officials, is a form of genocide.

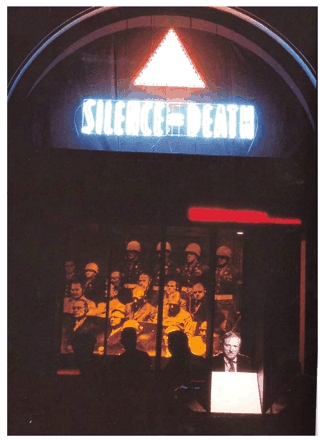

Inspired by Jonathan Mann’s early formulation of AIDS as a human rights issues, Edwin Cameron, a Justice on South Africa’s Supreme Court of Appeals, and Stephen Lewis, the UN Secretary General’s special envoy on AIDS in Africa, have argued that the failure of state officials and others, such as religious and industry leaders, to act effectively to curtail the epidemic border on crimes against humanity.3–5 Their statements echo analyses of the epidemic made by AIDS activists around the world. An early public version of this argument was an art installation created in 1987 by an ad hoc committee of ACT UP members for New York City’s New Museum of Contemporary Art. The piece, entitled “Let the Record Show. . .,” was installed in the Museum’s main windows on Broadway in lower Manhattan where passersby could view it as if it were another form of street demonstration (image above).

The piece presents a trial or official hearing. It includes a large photomural of the Nuremburg trials, referencing the concept of “crimes against humanity,” in front of which is placed cardboard cutouts of six public figures from the United States as if they are an additional row of defendants. Below each figure is a concrete plinth into which is placed statements for which she or he is to be held accountable. These figures and their records, literally “cast in stone,” are illuminated in turn so that viewers see the face of each defendant and read the record of their statements in turn:

Jerry Falwell, televangelist—“AIDS is God’s judgment of a society that does not live by His rules.”

William F. Buckley, columnist—“Everyone detected with AIDS should be tattooed in the upper forearm, to protect common needle users, and on the buttocks to prevent the victimization of other homosexuals.”

Jesse Helms, US Senator—“The logical outcome of testing is a quarantine of those infected.”

Cory SerVaas, Presidential AIDS Commission—“It is patriotic to have the AIDS test and be negative.”

Anonymous surgeon—“We used to hate faggots on an emotional basis. Now we have a good reason.”

The sixth accused is President Ronald Reagan, and before him is placed a blank slab of concrete, referencing his notorious seven-year public silence on the epidemic. Interrogating this silence from high above this scene is a version of the SILENCE= DEATH slogan rendered in bright pink neon. Below the neon sign, an LED displays running text that presents statistics, information on government inaction, and elaborations on the defendants’ records as follows:

Let the record show. . . In 1986, Dr. Cory SerVaas, editor of the Saturday Evening Post, announced that after working closely with the National Institutes of Health, she had found a cure for AIDS. At the time, the National Institutes of Health said they had never heard of Dr. Cory SerVaas. In 1987, President Reagan appointed Dr. Cory SerVaas to the Presidential AIDS Commission.

Let the record show. . . William F. Buckley deflects criticism of the government’s slow response to the epidemic through calculations: “At most three years were lost. Those three years have killed approximately 15000 people; if we are talking 50 million dead, then the cost of delay is not heavy.”

Let the record show. . . By Thanksgiving 1981, 244 known dead . . . no word from the President. By Thanksgiving 1982, 1123 known dead . . . no word from the President. By Thanksgiving 1987, 25 644 known dead . . . President Reagan: “I have asked the Department of Health and Human Services to determine as soon as possible the extent to which the AIDS virus has penetrated our society.”

While the figures and statements used in the installation are now outdated, the general method used by the artists is not. The work holds leaders accountable and presents the evidence necessary to evaluate their records. It also denaturalizes the epidemic by providing extensive, interdisciplinary documentation on the social production of the crisis, showing that a viral agent is not its sole pathogen but that pathological policies, ideas, and actions are significant contributing factors. Perhaps most important, however, is that the logo constructs and mobilizes power for those most affected by the epidemic, by shifting the objectifying analytic gaze away from so-called “risk practices” and “risk groups” and how they threaten the “general population” to a very different form of causal factors and responsible individuals.

Since 1987, the number of “AIDS criminals” has grown exponentially and includes many other heads of state, policymakers, religious leaders, and media figures. The list also includes military leaders, public health officials, and members of cabinets and advisory groups. In opposition, persons infected and affected by the epidemic have organized to shift the social economy of the epidemic in various parts of the world and have been joined, on rare occasions, by political leaders who have acknowledged the gravity of the crisis and have initiated interventions that demonstrate the capacity for large-scale reversals in infection and death rates.

This is a play of forces that has benefited greatly from the work of cultural activists. The interpretation of the epidemic, the interrogation and reconstruction of meanings and feelings, has been and will be one of the most important tools against the epidemic. Such work underscores the social dynamics that shape the epidemic, whether it be the stigmatizing attitudes that isolate a class of people from the resources they need to protect or treat themselves or the claim that health care is a human right, which enshrines the principle of universal access to care as a starting point for intervention and not the subject of debate.

The potency of the SILENCE= DEATH piece lies in its concentration of political, psychological, and historical insights into a highly abbreviated form so that it is not so much read or viewed as it is experienced. This piercing quality helps explain how the piece galvanized, gave focus to, and became the logo of a transnational social movement to which many of us owe our lives. Although the image may no longer circulate as it did 15 to 20 years ago, its legacy continues to benefit persons living with AIDS throughout the world. For those of us who do AIDS-related work, its arguments cut to the heart of the social crises that continue to produce and sustain the epidemic, such as stigma, discrimination, and the violation of fundamental human rights.

Figure 1.

“Let the Record Show . . .,“ an installation by members of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) in the windows of the New Museum of Contemporary Art on Broadway in New York City, 1987.

Contributors R. Sember wrote and revised the editorial with substantive contributions from D. Gere.

References

- 1.Crimp D. AIDS: cultural analysis/cultural activism. In: Crimp C, ed. AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press; 1989:3–16.

- 2.Meyer R. Vanishing point: art, AIDS, and the problem of visibility. In: Meyer R, ed. Outlaw Representation: Censorship and Homosexuality in 20th-Century American Art. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2002:224–275.

- 3.Mann JM. Human rights and AIDS: the future of the pandemic. In: Mann JM, Gruskin S, Grodin MA, Annas GJ, eds. Health and Human Rights: A Reader. New York: Routledge; 1999:216–222.

- 4.Cameron E. Witness to AIDS. New York: IB Taurus; 2005.

- 5.Lewis S. Race Against Time. Toronto: House of Anansi Press; 2005.