Abstract

Objective: To determine prevalence and predictors of depression among emergency department (ED) patients.

Method: For 1 week in November 2003, consecutive adult patients presenting to an urban ED from 8:00 a.m. to midnight were screened for a DSM-IV major depressive episode using the Harvard Department of Psychiatry National Depression Screening Day Scale. Patients who were severely ill or who had altered mental status were excluded. Demographic factors, psychiatric history, and brief medical history also were assessed.

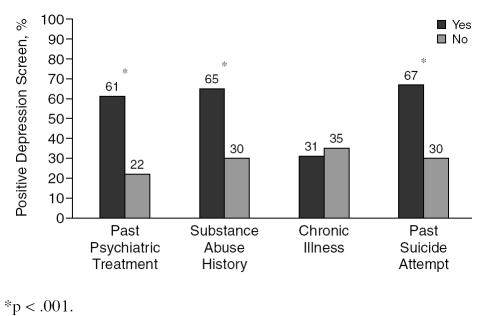

Results: Of 182 patients enrolled, 57 (32%, 95% CI = 25 to 39) screened positive for depression, which was much greater than general community estimates (6.6%, p < .0001). Depression was more likely (p < .001) in patients with a psychiatric history (61% vs. 22%), substance abuse history (65% vs. 30%), or a suicide attempt (67% vs. 30%). Eleven percent (95% CI = 7 to 17) of subjects endorsed suicidal ideation at least “some of the time.”

Limitations: This sample underrepresented severely ill, acutely distressed, or cognitively disabled patients. The most likely effect of these exclusion criteria was to yield an underestimate of depression. Also, the ED was located in a northeastern, urban city, which may not represent the rest of the country. Finally, we used a screening instrument without established operating characteristics within the ED setting.

Conclusion: Although findings suggest that depression is common, it is often ignored in the ED setting. Recent efforts to increase awareness of depression in outpatient medical settings may be warranted in EDs as well.

Depression is associated with enormous morbidity, mortality, disability, functional impairment, and costs.1–3 Despite the existence of numerous safe and effective antidepressant medications and psychotherapies, most people who suffer from depression do not receive the treatment they need.4,5 These facts, combined with the ease and cost-effectiveness of screening for depression, have led the United States Preventive Services Task Force to recommend broad-based screening for depression in health care settings.5

Efforts to increase such screening in primary care and outpatient settings have a long history.5,6 In contrast, little attention has been paid to the emergency department (ED), despite that EDs form a critical component of the nation's health care system with approximately 110 million ED visits occurring in 2002.7 In 2000, the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine's Public Health and Education Task Force concluded that the evidence was not sufficient to recommend for or against depression screening in the ED and encouraged more work to be done in this area.8 The successes observed with depression screening in outpatient settings, combined with the ED's vital role in identifying and treating diseases among segments of the population who would not otherwise find care, has led to further calls for increased attention to depression in the ED.9 Moreover, such efforts are generally consistent with the recent emphasis in emergency medicine to advance preventive medicine and public health efforts.10,11

The Harvard Department of Psychiatry's National Depression Screening Day Scale (HANDS) was created specifically to provide a brief, reliable, valid screening measure that maximizes sensitivity and specificity and could be used across a range of settings.12 We conducted a prospective screening study using the HANDS in a general adult ED population in an effort to provide preliminary data on prevalence and predictors of depression among general ED patients. We hypothesized that depression would be more common in the ED setting than in national community-based estimates and that depression would be more likely among patients with a psychiatric or substance abuse history and those who suffer from a chronic illness.

METHOD

Study Design and Participant Selection

This prospective, cross-sectional study was performed in November 2003. Using a protocol developed for the National Depression Screening Day (NDSD; http://www.mentalhealthscreening.org), investigators at an urban ED provided coverage during peak volume hours (8:00 a.m. to midnight) for 7 consecutive days. All patients ≥18 years old were considered for participation. Exclusion criteria included severe illness or distress (e.g., intubation, vomiting, possible sexual assault), contact precautions, cognitive insufficiency (e.g., dementia, intoxication, psychosis, coma), insurmountable language barrier, and refusal to participate. Hospital-provided, Spanish-speaking interpreters assisted with Hispanic patients.

Subjects were interviewed immediately prior to discharge from the ED or transfer to an inpatient floor. All patients were managed at the discretion of their treating physician. The research assistant (RA), upon conclusion of the interview, scored the screening questionnaire and gave all subjects who screened positive for depression an informational brochure and a referral list for out-patient treatment resources. Research assistants also encouraged subjects screening positive to discuss their symptoms with their primary care provider. The treating emergency physician or a mental health professional further assessed patients who endorsed suicidal ideation. The Institutional Review Board of the hospital approved the study, and informed consent was obtained for all participants.

Setting

The Department of Emergency Medicine at our institution is an academic, Level 1 trauma center serving a catchment area of approximately 2 million persons. The annual census is 49,000 visits per year, 30% of which are pediatric patients. The ED population is composed of 35% whites, 43% blacks, 20% Hispanics, and 2% other. Approximately 30% are commercially insured, 40% are government insured, and 30% are self-pay/no insurance. Approximately 29% are triaged as emergent, 49% as urgent, and 23% as routine. The admission rate is 13% to 15%.

Methods of Measurement, Data Collection, Data Processing

All participants were given the choice to complete the form themselves or via interview. The standard questions comprising the NDSD screening protocol were used, including demographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status), the HANDS, a brief psychiatric history, and a medical checklist. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ),13,14 which assesses bipolar disorder symptoms, was also collected; the MDQ data will be summarized in a separate article.

HANDS

The HANDS consists of 10 items based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, (DSM-IV)15 diagnostic criteria for major depressive episode. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale: 3 = all of the time, 2 = most of the time, 1 = some of the time, and 0 = none of the time. The item scores were summed, and each subject was categorized as unlikely (0 to 8), likely (9 to 16), or highly likely (17 to 30) to be depressed. To identify cases of depression, we collapsed the “likely” and “highly likely” categories to form 1 group (depression likely), as recommended by Baer and colleagues.12 Moreover, further evaluation by a physician was recommended for any individual who scored a 1 or higher on the suicide question, regardless of the total score. The HANDS has good internal consistency reliability (α= 0.87) and construct validity as evidenced by high correlations with other validated measures of depression.12 The sensitivity and specificity for the 9+ cutoff in a sample of community participants are 95% and 94%, respectively. A score of 17+ improves specificity to 100% but decreases sensitivity to 41%.

Psychiatric history

Patients indicated whether they had ever been treated for depression, bipolar disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or posttraumatic stress disorder. Because the sample size was not sufficient to detect differences between individual disorders, we created a dichotomous variable that represented treatment for any psychiatric condition (0 = no psychiatric condition, 1 = at least 1 psychiatric condition). One question also assessed whether the patient had ever attempted suicide.

Substance abuse history.

Patients indicated whether they had ever been treated for alcohol or drug abuse, which we converted into a dichotomous variable for any substance abuse (0 = no alcohol or drug abuse, 1 = yes alcohol or drug abuse).

Medical history

Patients indicated whether they had ever been treated for cancer, chronic pain, diabetes, heart disease/stroke, human immunodeficiency virus, seizure disorder, thyroid disorder, and asthma. We created a dichotomous variable that represented presence of any chronic disease (0 = no chronic disease, 1 = at least 1 chronic disease).

Study Hypotheses

Our primary hypothesis was that depression would be more common in the ED setting than in national community-based estimates. Our secondary hypothesis was that mood disorders would be more common among patients who (1) have a previous psychiatric treatment history, (2) have a previous substance abuse treatment history, or (3) suffer from a chronic illness.

Data Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 11.5 (Chicago, Ill.). Descriptive statistics are presented as proportions or means (with standard deviations). To test the primary hypothesis, we computed the sample proportion screening positive for depression and compared it with the general population estimates of a major depressive episode obtained from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R)1 using a single-sample χ2 test. The NCS-R was used because it represents the most methodologically sophisticated estimate of depression in the general population. Studies of equal sophistication using the HANDS or other depression screening instruments do not exist. Community estimates obtained during previous NDSDs are characterized by a strong self-selection bias due to the solicitation of people who suspect they may be suffering from depression, making such estimates unreliable and inappropriate for comparison.

The univariate associations between patient factors listed under the secondary hypotheses and the outcome variable were examined using χ2 tests. A multivariate logistic regression was computed to predict depression screening (positive or negative). Age and gender were controlled for because of their historical importance in predicting depression. Other variables associated with depression at p < .10 in univariate analyses were included in the multivariate model. Factors that retained significance after entry into the model were retained. All odds ratios (ORs) are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The final model was further evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow Goodness of Fit test. All p values were 2-sided, with p < .05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Of the 665 adult patients treated in the ED during the 7 days of the study, 556 presented during the hours of enrollment, and 379 were recorded on the study log. Fifty-seven were discharged before the RA could request consent, while 110 did not meet inclusion/exclusion criteria. Of those who were eligible (N = 212), 30 (14%) refused. In the end, 182 subjects (33% of total adult patients presenting during hours of enrollment) were enrolled. Unfortunately, because the study was anonymous, we were unable to collect any data from “missed” or excluded patients, making a comparison of the enrolled versus nonenrolled groups impossible. While we did not collect objective data on illness severity, such as triage category, admit status, diagnoses, or physician ratings, the exclusion criteria most likely led to a sample that underrepresented severely ill or emergent patients.

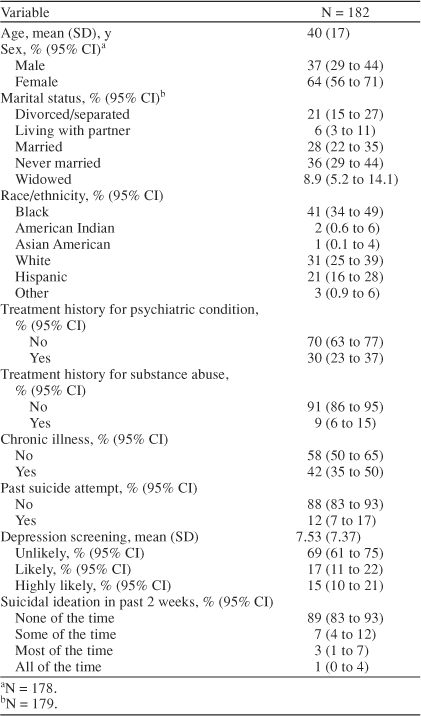

Table 1 summarizes the sample's demographic characteristics and descriptive statistics. The demographic characteristics were largely consistent with our ED as a whole, revealing strong representation by minorities, women, and the elderly. The internal consistency reliability of the HANDS was very good (α= 0.91). Nearly one third (32%, 95% CI = 25 to 39) screened in the “depression likely” range for depression, with 15% (95% CI = 10 to 21) being “highly likely” to be depressed. Approximately 11% (95% CI = 7 to 17) endorsed suicidal ideation at least “some of the time.”

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Adult Patients in an Urban Emergency Department

Primary Hypothesis

The prevalence of a positive screen for depression (point prevalence) in our sample was markedly higher than the NCS-R 12-month community prevalence of major depressive episode: 32% (95% CI = 25 to 39) versus 6.6% (95% CI = 5.9 to 7.3), respectively (p < .0001).

Secondary Hypotheses

As summarized in Figure 1, a positive screen for depression was more likely among patients with a treatment history for a psychiatric condition or substance abuse or with a past suicide attempt. Depression rates did not differ based on demographics or presence of a chronic illness.

Figure 1.

Predictors of Depression Among Adult Patients in an Urban Emergency Department

Controlling for age and sex, variables independently associated with depression (p < .05) were past psychiatric treatment (OR = 6.8, 95% CI = 3.1 to 15.0), past substance abuse treatment (OR = 3.9, 95% CI = 1.1 to 13.5), and past suicide attempt (OR = 3.2, 95% CI = 1.0 to 9.7). The model gave a good fit to the data with Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic of 11.9, with 8 degrees of freedom (p = .16).

DISCUSSION

Nearly one third (32%, 95% CI = 25 to 39) of our adult sample screened positive for depression at the time of their ED visit. Consistent with our primary hypothesis, these rates were much higher than the community estimates for 12-month prevalence of a major depressive episode (6.6%, 95% CI = 5.9 to 7.3).1 Even the NCS-R estimate of lifetime prevalence (16.2%, 95% CI = 15.1 to 17.3), which represents the upper boundary of community depression prevalence estimates, was approximately half the point prevalence of depression for our sample. Our estimates even surpassed depression rates among outpatient medical samples, which generally fall around 17% to 24% and are widely recognized to be much higher than community rates.16–18 Nevertheless, screening positive for depression is not equivalent to being diagnosed with a major depressive episode. Even screening instruments with laudable test characteristics such as the HANDS, which has a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 94% for detecting a DSM-IV–diagnosed major depressive episode,12 can yield high false positives.12,19 False positives may particularly occur in settings with higher base rates of depression, like medical settings. Many of the patients in our sample who screened positive for depression may have a subthreshold level of depression, transient depressed mood, or some other psychiatric condition. Using the more conservative cut-off value (HANDS score ≥17 or “highly likely”), which decreases the rate of false positives, we found that 15% of our sample remained positive for depression. This finding strongly suggests that depression is far more common among our sample of urban ED patients than in the general population, even when attempting to minimize false positive rates.

Reinforcing the validity of our results, the published studies examining depression among ED patients have found prevalence rates comparable to ours. Kumar and colleagues20 studied 539 general adult patients from 4 Boston, Mass., EDs using a single-item depression screen and found that 30% reported they had been depressed in the past 12 months. Similarly, approximately 30% of patients participating in a waiting-room computerized health behavior screening reported being depressed.21 Finally, approximately 27% to 32% of elderly ED patients screen positive for depression.22–24 These studies, though varied in design, methods, and measurement, corroborate our findings that approximately one third of ED patients are depressed.

Recently, Hazlett and colleagues24 studied a nationally representative sample of ED visits from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey.25 Psychiatric-related ED visits accounted for approximately 5.4% of all ED visits, increasing by 15% from 1992 to 2000. This study, while impressive in its breadth and scope, used retrospective reviews of billing/coding data, which is rife with limitations. It seems likely that their estimates grossly underrepresent the true prevalence of psychiatric conditions in ED patients. Results of our study, as well as those of others,20,22,23 show that prospectively screening patients reveals far more psychopathology than estimates derived from billing data or chart review.

Determining predictors of depression may help clinicians target their screening and counseling efforts. Consistent with our secondary hypotheses, depression was more likely in patients with a prior history of treatment for a psychiatric condition or substance abuse. These findings are not surprising. The NCS-R found that most lifetime (72%) and 12-month (79%) cases of major depressive episode had at least 1 comorbid DSM-IV disorder.1 What did surprise us was the rate of depression in those patients without a psychiatric or substance abuse treatment history, which ranged from 22% to 30%. Many patients who are depressed may not be receiving treatment,1 which buttresses the case for more broad-based screening.

One important reason to be concerned about depression is its relation to suicide. Twelve percent of our sample reported a past suicide attempt, with most of these also reporting current suicidal ideation at least “some of the time.” Not surprisingly, past suicide attempters had considerably elevated rates of depression, reinforcing the link between the 2 phenomena. Up to two thirds of those that complete suicide see a physician in the month preceding their death.5 Suicidal ideation should always be assessed in all patients who screen positive for depression.

Limitations

Our study had several potential limitations. First, we were only able to collect data on 27% of the adult patients who visited the ED during the time of the study. Most were missed because we did not have RAs available during the early morning hours or because the patient was discharged before the RA could enroll him/her. Additionally, of those that were recorded on the study log (N = 379), 110 (29%) were excluded because they were severely ill, acutely distressed, or cognitively disabled patients. The most likely effect of these exclusion criteria was to yield an underestimate of depression. Second, the ED was located in a northeastern, urban city, which may not represent the rest of the country. Third, we used a screening instrument that has not had its operating characteristics established for the ED setting. Although shown to be adequate in community solicited samples, the HANDS may be susceptible to inflated false positive rates in medical settings that are likely to have higher base rates of depression. Further study of the operating characteristics of the HANDS and other depression screening instruments is warranted.

Conclusion

Nearly one third of adult patients in the ED screened positive for depression. Although findings suggest mood disorders are common, especially among patients with prior psychiatric and substance abuse histories, these disorders are often ignored in the ED setting.9,22 Recent efforts to increase screening and awareness of affective disorders in medical settings (e.g., the NDSD) may be warranted in the ED as well as other outpatient settings.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse grant #DA-16698-01 (EDB).

Drs. Boudreaux, Cagande, Kilgannon, and Camargo and Ms. Kumar have no other significant commercial relationships relevant to the study.

REFERENCES

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, and Demler O. et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003 289:3095–3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349:1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Stewart A, and Hays RD. et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989 262:914–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Thase ME. Natural history and preventative treatment of recurrent mood disorders. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50:453–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:760–764. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-10-200205210-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schade CP, Jones ER, Wittlin BJ. A ten-year review of the validity and clinical utility of depression screening. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:55–61. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaig LF, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2002 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2004;340:1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock IC, Wyer PC, Gerson LW. Preventive care in the emergency department, pt 2: clinical preventive services: an emergency medicine evidence-based review. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Public Health and Education Task Force Preventive Services Work Group. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1042–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalenko T, Khare RK. Should we screen for depression in the emergency department? [editorial] Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:177–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KV, Gordon JA, Lowe RA. Preventive care in the emergency department, pt 1: clinical preventive services: are they relevant to emergency medicine? Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Public Health and Education Task Force Preventive Services Work Group. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1036–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider SM, Hamilton GC, and Moyer P. et al. Definition of emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 1998 5:348–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer L, Jacobs DG, and Meszler-Reizes J. et al. Development of a brief screening instrument: the HANDS. Psychother Psychosom. 2000 69:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemi SN, Miller CJ, and Berv DA. et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a new bipolar spectrum diagnostic scale. J Affect Disord. 2005 84:273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CJ, Klugman J, and Berv DA. et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire for detecting bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2004 81:167–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC, Fechner-Bates S, Schwenk TL. Prevalence, nature and comorbidity of depressive disorders in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1994;16:267–276. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Shea S, and Feder A. et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders in an urban general medicine practice. Arch Fam Med. 2000 9:876–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung WW. The role of rating scales in the identification and management of the depressed patient in the primary care setting. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51(5, suppl):72–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zich JM, Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK. Screening for depression in primary care clinics: the CES-D and the BDI. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1990;20:259–277. doi: 10.2190/LYKR-7VHP-YJEM-MKM2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Clark S, and Boudreaux ED. et al. A multicenter study of depression among emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2004 11:1284–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KV, Lauderdale DS, and Stocking CB. et al. Better health while you wait: a controlled trial of a computer-based intervention for screening and health promotion in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2001 37:284–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldon SW, Emerman CL, and Schubert DS. et al. Depression in geriatric ED patients: prevalence and recognition. Ann Emerg Med. 1997 30:141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raccio-Robak N, McErlean MA, and Fabacher DA. et al. Socioeconomic and health status differences between depressed and nondepressed ED elders. Am J Emerg Med. 2002 20:71–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazlett SB, McCarthy ML, and Londner MS. et al. Epidemiology of adult psychiatric visits to US emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2004 11:193–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaig LF, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2001 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2003;335:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]