Abstract

Mitochondrial genomes of multicellular animals are typically 15- to 24-kb circular molecules that encode a nearly identical set of 12–14 proteins for oxidative phosphorylation and 24–25 structural RNAs (16S rRNA, 12S rRNA, and tRNAs). These genomes lack significant intragenic spacers and are generally without introns. Here, we report the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the placozoan Trichoplax adhaerens, a metazoan with the simplest known body plan of any animal, possessing no organs, no basal membrane, and only four different somatic cell types. Our analysis shows that the Trichoplax mitochondrion contains the largest known metazoan mtDNA genome at 43,079 bp, more than twice the size of the typical metazoan mtDNA. The mitochondrion’s size is due to numerous intragenic spacers, several introns and ORFs of unknown function, and protein-coding regions that are generally larger than those found in other animals. Not only does the Trichoplax mtDNA have characteristics of the mitochondrial genomes of known metazoan outgroups, such as chytrid fungi and choanoflagellates, but, more importantly, it shares derived features unique to the Metazoa. Phylogenetic analyses of mitochondrial proteins provide strong support for the placement of the phylum Placozoa at the root of the Metazoa.

Keywords: animal evolution, phylogenetics

Trichoplax adhaerens [Shulze 1883] is a marine invertebrate distributed in tropical waters worldwide (1–3). It is the simplest known free-living animal, displaying no axis of symmetry, lacking a basal membrane, possessing only four somatic cell types (4–6), and having one of the smallest known animal genomes (7–9). Until recently, T. adhaerens was the sole representative of the phylum Placozoa, but recent field studies and molecular analyses indicate genetic diversity underlying apparent morphological uniformity within the Placozoa (3, 10). In the laboratory, placozoans reproduce asexually by either binary fission or budding dispersive propagules called swarmers. Eggs have been observed, and recent DNA polymorphism analysis has provided evidence for sexual reproduction within the Placozoa (10).

The phylogenetic placement of Placozoa among the metazoans, i.e., the animals, remains unresolved. In particular, its placement among lower metazoans, that is, the phyla Cnidaria, Ctenophora, and Porifera, has been controversial. Most studies place Porifera at the base of the metazoan tree of life (11–15), but others support placozoans as one of the earliest branching lineages of Metazoa (16–20). Conflicting data, including 18S, 28S, and 16S analysis, have suggested that Placozoa form a sister clade to all bilaterians or a sister clade to both cnidarians and bilaterians (14, 21–27).

Comparative mitochondrial genomics is becoming an effective tool to resolve phylogenetic placements because of several unique properties of mitochondrial genomes, including uniparental inheritance, orthologous genes, and lack of substantial intermolecular recombination (reviewed in refs. 28–30). Although some have questioned the utility of comparative mitochondrial genomics based on problems of convergence (31), in many cases, mitochondrial data have provided robust phylogenetic trees capable of resolving evolutionary relationships among fungi (32), protists (33), diploblasts (34), and bilaterians (35–42).

The closest living relatives of animals, the choanoflagellates and fungi, possess large mitochondrial genomes with extensive intragenic spacers, introns, and several ORFs of unknown function. The unicellular choanoflagellate, Monosiga brevicollis, has mtDNA that is nearly four times larger (76,568 bp) than the typical animal mtDNA genome and encodes 55 different genes, often separated by large intragenic spacer regions, including two genes interrupted by introns (43). Metazoans, on the other hand, have compacted 15- to 20-kb circular mitochondrial genomes that encode a nearly identical set of 12–14 proteins for oxidative phosphorylation and 24–25 structural RNAs (16S rRNA, 12S rRNA, and tRNAs) without significant intragenic spacers and, generally, without introns. Mitochondrial DNA variants exist in metazoans, such as the presence of type I introns and linear mtDNA molecules found in cnidarians (34, 44, 45), the presence of the atp9 gene in sponges (15, 46), and the secondary expansion of mtDNA found in some mollusks (47, 48) and insects (49).

Our analysis shows that the Trichoplax mitochondrion possesses the largest known metazoan mtDNA genome, at 43,079 bp, more than twice the size of the typical metazoan mtDNA. Its large size is due not to secondary expansion but to features shared with metazoan outgroups, such as intragenic spacers, several introns, ORFs of unknown function, and protein-coding regions that are generally larger than that found in animals. The large Trichoplax mtDNA is the least derived mitochondrial genome of any animal. Moreover, the Trichoplax mitochondrion shares unique derived features with other lower metazoans, notably the loss of all ribosomal protein genes. These structural features of the Trichoplax mitochondrial genome, along with Bayesian and maximum-likelihood (ML) analyses of mitochondrial proteins from metazoans and outgroups, provide robust support for the phylogenetic placement of the phylum Placozoa at the root of the Metazoa.

Results and Discussion

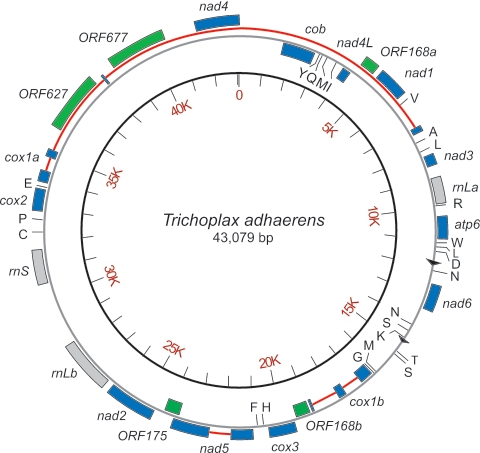

We cloned the full-length mitochondrial genome from the placozoan T. adhaerens, determined its complete sequence and organization (Fig. 1), and compared it with the mtDNA genomes of other diploblasts (15, 44, 45) and the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis (43). The 43,079-bp circular mtDNA genome of Trichoplax is more than twice the size of the mtDNA found in most metazoans (17–25 kb), including those of poriferans (15, 46) and cnidarians (44, 45) (Table 1), making it the largest known animal mtDNA genome. The size and composition of the Trichoplax mtDNA genome resembles that of the choanoflagellates and is in striking contrast to the streamlined genomes found in virtually all metazoans. In rare cases of relatively large mtDNAs (up to 42 kb) found in animals, these instances are known to be a result of secondary duplications, repeat expansions, or extensive A + T-rich regions (47–49).

Fig. 1.

Scale drawing of the mitochondrial genome of T. adhaerens. The complete sequence of the 43,079-bp mitochondrial genome from a Red Sea isolate of T. adhaerens (59) was determined and annotated by identifying ORFs with the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s orf finder using genetic code 4. Known mitochondrial proteins (blue rectangles) were identified by blast and by alignment to corresponding proteins found in poriferans (NC_006894, NC_006990, and NC_006991), cnidarians (NC_000933 and NC_003522), and the choanoflagellate Monosiga (NC_004309) to infer the start of translation. Genes transcribed in the clockwise direction are shown on the outer circumference; genes transcribed in the counterclockwise direction are shown on the inner circumference. Large (rnLa and rnLb) and small (rnS) ribosomal genes are represented as gray rectangles. The tRNAs (black lines) were identified by using trnascan-se (62) and are annotated by their International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) amino acid codes. ORFs encoding unknown proteins >100 aa in length are identified by their amino acid coding capacity (green rectangles). Introns in the cox1 and nad5 genes are shown as red lines connecting exons (blue rectangles). A 103-bp imperfect direct repeat is shown as black triangles. Note that the carboxy-terminal region of cox1 (exons 5–7) is inverted with respect to cox1 exons 1–4 because of the presence of a large 16-kb inversion encompassing the region from trnP to trnV. This inversion has been confirmed experimentally in the Red Sea isolate but does not exist in another placozoan taxon (A. Signorovitch, L. Buss, and S.L.D., unpublished data).

Table 1.

Comparison of representative mitochondrial genomes

| Organism | Size, bp | Coding, % | tRNAs | rRNA | ORFs | Introns | RPs | RC subunits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choanoflagellata | ||||||||

| Monosiga | 76,568 | ≈47 | 25 | rrnL, rrnS | 6 | 4 | rps 3, 4, 8, 12–14, 19 | atp 6, 8, 9, cob, cox 1–3, nad1–4, 4L, 5, 6 |

| Placozoa | ||||||||

| Trichoplax | 43,079 | ≈50 | 24 | rrnLa, rrnLb, rrnS | 5 | >3 | 0 | atp 6, cob, cox 1–3, nad1–4, 4L, 5, 6 |

| Porifera | ||||||||

| Axinella | 25,610 | ≈76 | 25 | rrnL, rrnS | 0 | 0 | 0 | atp 6, 8, 9, cob, cox 1–3, nad1–4, 4L, 5, 6 |

| Geodia | 18,020 | ≈98 | 24 | rrnL, rrnS | 0 | 0 | 0 | atp 6, 8, 9, cob, cox 1–3, nad1–4, 4L, 5, 6 |

| Tethya | 19,565 | ≈92 | 25 | atp 6, 8, 9, cob, cox 1–3, nad1–4, 4L, 5, 6 | ||||

| Cnidaria | ||||||||

| Metridium | 17,443 | ≈86 | 2 | rrnL, rrnS | 1 | 2 | 0 | atp 6, 8, cob, cox 1–3, nad1–4, 4L, 5, 6 |

| Acropora | 18,338 | ≈85 | 2 | rrnL, rrnS | 0 | 1 | 0 | atp 6, 8, cob, cox 1–3, nad1–4, 4L, 5, 6 |

Data compiled from mitochondrial genomes taken from GenBank: Monosiga brevicollis (NC_004309), T. adhaerens (this study) the poriferans Axinella corrugata (NC_006894), Geodia neptuni (NC_006990), and Tethya actini (NC_006991), and the onidarians Metridium senile (NC_000933) and Acropora tenuis (NC_003522). Coding percentage calculated from the proportion of sequence having protein coding (known mitochondrial proteins or ORF >100 aa) tRNA genes, and rRNA coding sequences; ORFs, number of reading frames encoding unknown proteins >100 aa; RPs, ribosomal protein genes; RC subunits, respiratory chain subunit genes.

The Trichoplax mtDNA genome encodes a typical complement of animal mtDNA genes, including ATP synthase subunits (atp6), cytochrome oxidase subunits (cox1, cox2, and cox3), apocytochrome b (cob), reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide ubiquinone oxireductase subunits (nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad5, and nad6), a full complement of tRNAs (24 in all), and small and large ribosomal RNAs (rrnS and rrnL) (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Additional features of the Trichoplax mtDNA include extra introns in the cox1 gene and the physical separation of the rrnL and cox1 genes into two discrete domains (Fig. 1). Several unknown ORFs are also found in the Trichoplax mitochondrial genome, including one that encodes a 627-aa protein containing reverse transcriptase (pfam00078) and Type II intron maturase (pfam01348) domains, located just downstream of the second exon of cox1. We have not identified the atp8 gene in Trichoplax mtDNA.

Notably, Trichoplax mtDNA shares characteristics found in the mitochondrial genomes of known metazoan outgroups. The large size of the Trichoplax genome is due to the presence of large intragenic spacers, several ORFs of unknown function, and additional cox1 introns, two of which share identical positions within the choanoflagellate Monosiga and the fungus Monoblepharella cox1 genes (32, 43). Furthermore, most mtDNA genes in Trichoplax encode larger proteins than those found in other animals. On average, protein-coding regions are 10% larger in Trichoplax than in other diploblasts, which is comparable to the difference between choanoflagellates and diploblasts (43). Similar to Monosiga (43), only about half of the Trichoplax mtDNA contain coding regions, whereas other diploblast mtDNA genomes range from 76% to 98% coding capacity in the 25.6- and 18-kb mtDNAs of the poriferans Axinella and Geodia (15, 46), respectively (Table 1).

The Trichoplax mitochondrial genome shares metazoan features lacking in choanoflagellates and fungi. Notably, we find no evidence of the presence of ribosomal protein genes in Trichoplax, a property shared with other metazoan mtDNAs, suggesting that loss of ribosomal protein genes may be a synapomorphy for the animal kingdom. Mitochondrial DNA features that had heretofore been thought to be restricted to either sponges or cnidarians are all found in Trichoplax. Specifically, the mitochondrial genomes of both cnidarians and Trichoplax mtDNA have conserved introns in the nad5 and cox1 genes as well as unknown ORFs.

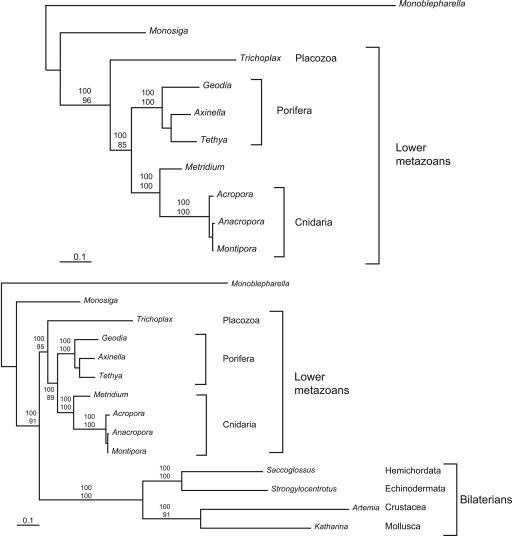

To further examine the phylogenetic position of Trichoplax among the lower metazoans, we performed Bayesian and ML analyses on 2,730 amino acid positions derived from 12 well conserved protein sequences (cox1–3, cob, atp6, nad1–4, 4L, and 5–6) common to the mitochondrial genomes of T. adhaerens; the cnidarians Metridium senile (NC_000933), Acropora tenuis (NC_003522), Anacropora matthai (NC_006898), and Montipora cactus (NC_006902); the poriferans Geodia neptuni (NC_006990), Axinella corrugata (NC_006894), and Tethya actinia (NC_006991); and the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis (NC_004624). Monoblepharella sp. JEL15 (NC_004624) was included as an outgroup taxon for this analysis because chytrids are regarded as the basal fungal taxon (32). The predicted amino acid sequences for each of the 12 genes were aligned by using clustalw (50) and edited, manually and computationally, by using gblocks (51), to remove ambiguous sites. These alignments were concatenated to produce a final data set of 2,730 aa (see Data Set 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Partitioned Bayesian analysis, implemented in mrbayes 3.1.1 (52), was performed by using the mtREV amino acid substitution model, with substitution-rate variation among sites modeled by a discrete approximation of the γ-distribution with a proportion of invariable sites (I + Γ). This analysis produced the phylogeny depicted in Fig. 2A. The posterior probabilities exceeded 99% for each node, with overwhelming support for Trichoplax being basal to both poriferans and cnidarians. ML analysis, implemented in paml 3.14 (53), using star decomposition tree search and the mtREV amino acid substitution model, produced an identical tree topology with the bootstrap values shown in Fig. 2. Using site-wise log-likelihoods generated by paml, statistical tests, implemented in consel 0.1i (54), were conducted to test all possible placements of Trichoplax among lower metazoans (Table 2). The P values of the Approximately Unbiased (55), the weighted and unweighted Kishino–Hasegawa (56), and the weighted and unweighted Shimodaira–Hasegawa (55) tests all exceeded 0.999 for the tree shown in Fig. 2A, with no other topology supported by P values >0.002.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of concatenated mitochondrial proteins. The data set consisted of a total of 2,730 amino acid positions concatenated from 12 mitochondrial protein sequences (atp6 cob, cox1–3, nad1–4, and 4L, 5, and 6). Partitioned Bayesian analysis was performed with mrbayes for 500,000 generations by using four chains and the mtREV amino acid substitution model. Substitution rate variation among sites was modeled by a discrete approximation of the γ-distribution with a proportion of invariable sites (I + Γ). ML analysis performed with paml using the mtREV amino acid substitution model and star decomposition tree search gave an identical tree topology. Posterior probability (Upper) and bootstrap (Lower) values are shown for each node. In these analyses, the output trees were rooted by using the chytrid fungus Monoblepharella.

Table 2.

consel statistical tests of the tree topology obtained by Bayesian and ML analysis

| Hypothesis |

P |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| au | kh | wkh | sh | wsh | pp | |

| Trichoplax basal to Porifera + Cnidaria | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Trichoplax within Porifera | 10−44–10−4 | 0–0.001 | 0–0.001 | 0–0.113 | 0–0.002 | 10−111–10−29 |

| Porifera basal to Trichoplax + Cnidaria | 10−104–10−4 | 0–10−4 | 0–10−4 | 0–0.073 | 0–10−4 | 10−291–10−33 |

Summary of statistical tests on all possible phylogenetic positions of Trichoplax within lower metazoans by using the Approximately Unbiased (54), the weighted and unweighted Kishino–Hasegawa (55); and the weighted and unweighted Shimodaira–Hasegawa (54) tests, as implemented in consel. In addition, posterior probabilities pp are also displayed.

Inclusion of bilaterian mtDNA data from the deuterostomes Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (NC_001453) and Saccoglossus kowalevskii (NC_007438) and the protostomes Artemia franciscana (NC_001620) and Katharina tunicata (NC_001636) in the phylogenetic analyses yielded a bifurcation at the base of metazoans between two clades (Fig. 2B), one comprising all bilaterians and the other comprising all diploblasts. Inclusion of additional bilaterian taxa in the analysis did not change this topology (data not shown). This result is consistent with that reported by Lavrov et al. (15) and may be due to long branch attraction that is known to affect analyses of fast evolving metazoan sequences (57). A relative-rates test comparing bilaterians to diploblasts using Monosiga and Monoblepharella as outgroups was performed by using rrtree (58). The P value for bilaterians evolving at the same rate as diploblasts was 10−7, indicating that the conditions for long branch attraction are present. Most importantly, regardless of whether bilaterian sequences are included or not, the basal phylogenetic position of Placozoa within the lower metazoans is robust, with P values between 0.924 and 1.000 for the various statistical tests (see Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Finally, the “placozoan-basal” topology was robust to the choice of outgroups, including the addition or substitution of chytrid fungi (Allomyces macrogynus NC_001715 and Rhizophydium sp. 136 NC_003053) as outgroups (see Fig. 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Our results demonstrate that the placozoan Trichoplax possesses an unusual and unique mitochondrial genome, with structural and compositional features characteristic of both choanoflagellate mtDNAs, the closest relatives to animals, and typical lower metazoan mtDNAs. Like choanoflagellates, the Trichoplax mtDNA is much larger than the typical metazoan mtDNA, with substantial noncoding regions, genes generally larger than those found in other metazoans, several unknown ORFs, and conserved introns in both nad5 and cox1 genes. The large mtDNA genome found in Trichoplax, although consistent with the idea that marked gene loss and mtDNA compaction occurred during the emergence of multicellular animals, nonetheless indicates that pronounced compaction was not coincident with the origin of the Metazoa.

Texts of invertebrate zoology have long been unanimous in placing the Porifera as the basal metazoan phylum, based largely on the striking resemblance of the collared cells of choanoflagellates to the choanocytes of sponges. Choanocytes, however, are adaptations for filter-feeding in these two taxa, and their absence is expected in placozoans, which have a different mode of feeding. The data and analyses presented here provide strong support for the phylogenetic placement of Placozoa as the basal extant lower metazoan phylum.

Materials and Methods

Cloning and Sequencing of T. adhaerens Mitochondrial DNA.

Total genomic DNA was isolated from a cultured Red Sea isolate (59). Approximately 20 μg of genomic DNA was resuspended in 0.5 ml of Tris-EDTA buffer, sheared by two quick passages through a 20-gauge needle attached to a 1-ml syringe, end-repaired by using the DNA Terminator Kit (Lucigen, Middleton, WI) and size fractionated by pulse-field electrophoresis. The 30- to 40-kb DNA fraction was gel purified, ligated into the pCC1FOS vector, packaged in vitro, and plated on EPI300 Escherichia coli cells according to manufacturer’s instructions (EPICENTRE Biotechnologies, Madison, WI). Several independent, overlapping fosmid clones containing near-full-length (36- to 40-kb) mitochondrial DNA inserts were identified by colony hybridization using a 16S rRNA probe (27). Purified fosmid DNA was isolated and sheared by sonication and end-repaired and fractionated by gel electrophoresis. The 2- to 4-kb fraction was gel purified and ligated to pSMART LC-Kan vector and transformed into E. coli 10G-competent cells according to manufacturer’s instructions (Lucigen). Approximately 384 random subclones were chosen for sequencing. Template DNA was prepared by using TempliPhi amplification (GE Healthcare) and sequenced by BigDye Terminator version 3.1 cycle sequencing on ABI PRISM 3700 DNA analyzers (Applied Biosystems) with both forward and reverse vector primers (Lucigen). Selected regions of poor quality or low coverage were resequenced by using fosmid DNA template and custom DNA primers designed by the Autofinish feature of consed (60).

Sequence Assembly and Annotation.

DNA sequence chromatograms generated from random subclones and custom primer sequencing were processed and assembled by using the phred–phrap–consed software suite release 13.0 (www.phrap.org). The assembled mitochondrial genome sequence was analyzed with the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s orf finder using genetic code 4. Predicted ORFs were subjected to a similarity search using blastp. A custom-made Perl script, available upon request, automated this process. Each identified mitochondrial protein sequence was aligned to the corresponding sequences from related taxa, including poriferans (NC_006894, NC_006990, and NC_006991), cnidarians (NC_000933, NC_003522, NC_006898, and NC_006902), and the choanoflagellate Monosiga (NC_004309) to infer translational start sites, intron–exon boundaries, and estimated boundaries of ribosomal RNA genes. The transfer RNAs were identified with trnascan-se 1.21 (www.genetics.wustl.edu/eddy/tRNAscan-SE). Twelve conserved mitochondrial proteins (atp6, cox1–3, cob, nad1–4, and 4L, 5, and 6) from Trichoplax, and other species were individually aligned by using clustalw (50), edited manually and computationally by using gblocks (51) to remove ambiguous sites, and concatenated to give a final data set of 2,730 aa for phylogenetic analysis (Data Set 1).

Phylogenetic Analysis.

Partitioned Bayesian analysis, as implemented in mrbayes 3.1.1 (52), was performed for 500,000 generations by using four independent chains and the mtREV amino acid substitution model. Substitution-rate variation among sites was modeled by a discrete approximation of the γ-distribution with a proportion of invariable sites (I + Γ). The first 1,250 samples (25%) were discarded as burn-in. ML analysis, implemented in paml 3.14 (53), was performed by using the mtREV amino acid substitution model and star decomposition tree search. For bootstrap analysis, 100 resampling replicates were generated by using seqboot (61) and analyzed by ML analysis using paml. The topology given by mrbayes and paml was statistically tested for robustness against other possible tree topologies with consel 0.1i (54) using site-wise log-likelihood outputs from paml.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rafael Rosengarten, Ana Signorovitch, Anahid Powell, Michael Donahue, and Matthew Nicotra for suggestions and critical reading. This work was supported by a Human Frontiers Science Program grant (to S.L.D. and B.S.) and a National Science Foundation Genome-Enabled Environmental Science and Engineering Program grant (to S.L.D., M.A.M., and L.W.B.).

Abbreviations

- ML

maximum likelihood.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. DQ112541).

References

- 1.Grell K. C. An. Inst. Cienc. del Mar y Limnol. Univ. Nat. Auton. Mex. 1987;14:255–256. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearse V. B. Pac. Sci. 1989;43:117–121. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voigt O., Collins A. G., Pearse V. B., Pearse J. S., Ender A., Hadrys H., Schierwater B. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:R944–R945. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grell K. G. Encyclopaedla Cinematographica Inst. wiss. Film. Göttingen: 1973. Film E 1918. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulze F. E. Phys. Abh. Kgl. Akad. Wiss. Berlin. 1891:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulze F. E. Zool. Anz. 1883;6:92–97. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birstein V. J. Biol. Zentralbl. 1989;108:63–67. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruthmann A., Wenderoth H. Cytobiologie. 1975;10:421–431. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruthmann A. Cytobiologie. 1977;15:58–64. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Signorovitch A. Y., Dellaporta S. L., Buss L. W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15518–15522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504031102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schutze J., Krasko A., Custodio M. R., Efremova S. M., Muller I. M., Muller W. E. Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B; 1999. pp. 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller W. E., Kruse M., Koziol C., Muller J. M., Leys S. P. Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biol. 1998;21:141–156. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72236-3_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medina M., Collins A. G., Silberman J. D., Sogin M. L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:9707–9712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171316998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins A. G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:15458–15463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavrov D. V., Forget L., Kelly M., Lang B. F. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:1231–1239. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grell K. G. Origine dei Grandi Phyla dei Metazoi. Rome: Acc. Naz. Lincei, Gonvegno Int.; 1981. pp. 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grell K. G. Naturwiss. Rundsch. 1971;24:160–161. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivanov D. L., Malakhov V. V., Tzetlin A. B. Zool. Zh. 1980;59:1765–1767. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Syed T., Schierwater B. Senckenbergiana Lethaea. 2002;82:259–270. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Syed T., Schierwater B. Vie Milieu. 2002;52:177–187. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cavalier-Smith T. Biol. Rev. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 1998;73:203–266. doi: 10.1017/s0006323198005167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins A. G. J. Evol. Biol. 2002;15:418–432. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J., Kim W., Cunningham C. W. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999;16:423–427. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Podar M., Haddock S. H., Sogin M. L., Harbison G. R. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2001;21:218–230. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2001.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawlowski J., Montoya-Burgos J.-I., Fahrni J. F., Wüest J., Zaninetti L. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1996;13:1128–1132. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christen R., Ratto A., Baroin A., Perasso R., Grell K. G., Adoutte A. EMBO J. 1991;10:499–503. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07975.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ender A., Schierwater B. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003;20:130–134. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolstenholme D. R. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1992;141:173–216. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lang B. F., Seif E., Gray M. W., O’Kelly C. J., Burger G. J. Eukaryotic Microbiol. 1999;46:320–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb04611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lang B. F., Gray M. W., Burger G. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1999;33:351–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curole J. P., Kocher T. D. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1999;14:394–398. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(99)01660-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bullerwell C. E., Forget L., Lang B. F. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1614–1623. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lang B. F., O’Kelly C., Nerad T., Gray M. W., Burger G. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1773–1778. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bridge D., Cunningham C. W., Schierwater B., DeSalle R., Buss L. W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:8750–8753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saitoh K., Miya M., Inoue J. G., Ishiguro N. B., Nishida M. J. Mol. Evol. 2003;56:464–472. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2417-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larget B., Simon D. L., Kadane J. B., Sweet D. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:486–495. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yokobori S., Watanabe Y., Oshima T. J. Mol. Evol. 2003;57:574–587. doi: 10.1007/s00239-003-2511-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scouras A., Beckenbach K., Arndt A., Smith M. J. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2004;31:50–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mindell D. P., Sorenson M. D., Dimcheff D. E., Hasegawa M., Ast J. C., Yuri T. Syst. Biol. 1999;48:138–152. doi: 10.1080/106351599260490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Phillips M. J., Penny D. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2003;28:171–185. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.San Mauro D., Gower D. J., Oommen O. V., Wilkinson M., Zardoya R. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2004;33:413–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murata Y., Nikaido M., Sasaki T., Cao Y., Fukumoto Y., Hasegawa M., Okada N. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2003;28:253–260. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burger G., Forget L., Zhu Y., Gray M. W., Lang B. F. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:892–897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336115100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Oppen M. J., Catmull J., McDonald B. J., Hislop N. R., Hagerman P. J., Miller D. J. J. Mol. Evol. 2002;55:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00239-001-0075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beagley C. T., Okimoto R., Wolstenholme D. R. Genetics. 1998;148:1091–1108. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.3.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lavrov D. V., Lang B. F. Trends Genet. 2005;21:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rigaa A., Monnerot M., Sellos D. J. Mol. Evol. 1995;41:189–195. doi: 10.1007/BF00170672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fuller K. M., Zouros E. Curr. Genet. 1993;23:365–369. doi: 10.1007/BF00310901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boyce T. M., Zwick M. E., Aquadro C. F. Genetics. 1989;123:825–836. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.4.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Castresana J. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000;17:540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huelsenbeck J. P., Ronquist F. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang Z. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1997;13:555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shimodaira H., Hasegawa M. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1246–1247. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shimodaira H. Syst. Biol. 2002;51:492–508. doi: 10.1080/10635150290069913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kishino H., Hasegawa M. J. Mol. Evol. 1989;29:170–179. doi: 10.1007/BF02100115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anderson F. E., Swofford D. L. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2004;33:440–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Robinson-Rechavi M., Huchon D. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:296–297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.3.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grell K. G. Z. Morphol. Tiere. 1972;73:297–314. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gordon D., Desmarais C., Green P. Genome Res. 2001;11:614–625. doi: 10.1101/gr.171401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Felsenstein J. phylip: Phylogeny Inference Package. Seattle: University of Washington; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lowe T. M., Eddy S. R. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.