Abstract

Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage is a rare clinical entity; signs and symptoms include pain, hematuria, and shock. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage can be caused by tumors, such as renal cell carcinoma and angiomyolipoma; polyarteritis nodosa; and nephritis. The least common cause is segmental arterial mediolysis. Although computed tomography is used for the diagnosis of spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage, it can miss segmental arterial mediolysis as the cause of the hemorrhage. The diagnosis of segmental arterial mediolysis as a cause of spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage requires angiography, with pathologic confirmation for a definitive diagnosis.

Keywords: Retroperitoneal hemorrhage, Segmental arterial mediolysis, Case report

A 32-year-old Hispanic G7P5116 woman with a history of 2 uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs), hepatitis C, sickle cell trait, heart murmur, bilateral asymptomatic renal calculi, asthma, easy bruising, placental abruption, and heavy menstruation presented to the emergency department with a temperature of 103°F and irritative voiding symptoms. Results of urinalysis were positive, and she was presumptively diagnosed with a UTI and discharged home with a prescription for oral levofloxacin. The patient returned 2 days later with persistent left flank pain and nausea. A non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan revealed small, bilateral, nonobstructing calculi without hydronephrosis or masses. The patient was discharged home with a prescription for oral ciprofloxacin. On the day of admission, the patient presented with increasing left flank pain and abdominal distention. She denied hematuria, irritative voiding symptoms, fever, mouth sores, rash, arthralgias, myalgias, melena, bright red blood per rectum, headaches, neurologic symptoms, or weight loss. She had no history of trauma. Her parents are consanguineous. She had no known allergies and was taking no medications at the time of admission.

On physical examination, the patient was afebrile, her blood pressure was 126/80 mm Hg, and her vital signs were stable. She demonstrated left costovertebral angle tenderness and left upper and lower quadrant abdominal tenderness with minimal distention. Results of a basic metabolic panel, coagulation studies, and complete blood cell count were all normal; hematocrit was 39.8. The following morning the patient had a slight increase in abdominal distention. A CT revealed a 6-cm left perinephric hematoma without evidence of renal mass (Figure 1). A repeat hematocrit was 20.6, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit with a blood pressure of 189/85 mm Hg. She received a transfusion of 3 units of packed red blood cells (PRBCs) and was sent for angiography, which revealed no active bleeding but did show multiple small microaneurysms in the periphery of the kidney consistent with polyarteritis nodosa (Figure 2), for which the patient was given steroids.

Figure 1.

CT scan, obtained the day after admission because the patient’s abdomen became distended, revealed a large left perinephric hematoma.

Figure 2.

Initial angiography failed to demonstrate any active bleeding, but several microaneurysms were seen in the peripheral regions of the renal cortex. These aneurysms are usually suggestive of polyarteritis nodosa.

Laboratory tests confirmed that the patient was sickle screen positive, but her erythrocyte sedimentation rate, coagulation studies, platelet function, complement studies, and rheumatoid factor were all within normal limits. The patient remained hemodynamically stable but continued to require blood products and diltiazem hydrochloride (Cardizem; Biovail Corporation, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) to control her blood pressure. A repeat angiography on hospital day 3 revealed resolution of the microaneurysms and replacement with several blind-ending vessels in the left kidney (Figure 3). The patient’s right kidney and celiac axis were normal. By hospital day 5, the patient had received 10 units of PRBCs, 4 units of fresh frozen plasma, and 5 units of platelets. A repeat CT scan showed an increase in the size of the left perinephric hematoma from 6 to 10.25 cm with extension into the pelvis, free blood in the peritoneum, a lateral infarct of the left kidney, and large, bilateral pleural effusions (Figure 4). The patient was taken to the operating room, where a partial nephrectomy was attempted. Despite control of the renal vasculature, uncontrolled renal hemorrhage occurred, and a left nephrectomy with evacuation of the hematoma was performed. Intraoperatively she received 7 units of PRBCs, 4 units of fresh frozen plasma, 25 units of cryoprecipitate, and 15 units of platelets. The patient’s recovery was uneventful and she was discharged on postoperative day 3.

Figure 3.

Repeat angiography performed 2 days after the initial on showed that the patients’s microaneurysms had been replaced by several blind-ending vessels. The patient’s right kidney and celiac axis were normal (not shown).

Figure 4.

Repeat CT scan obtained 4 days after the patient’s initial CT showed that the perinephric hematoma had increased from 6 to 10.25 cm and extended into the pelvis. Additional cuts revealed free blood in the peritoneum and a infarct of the left kidney.

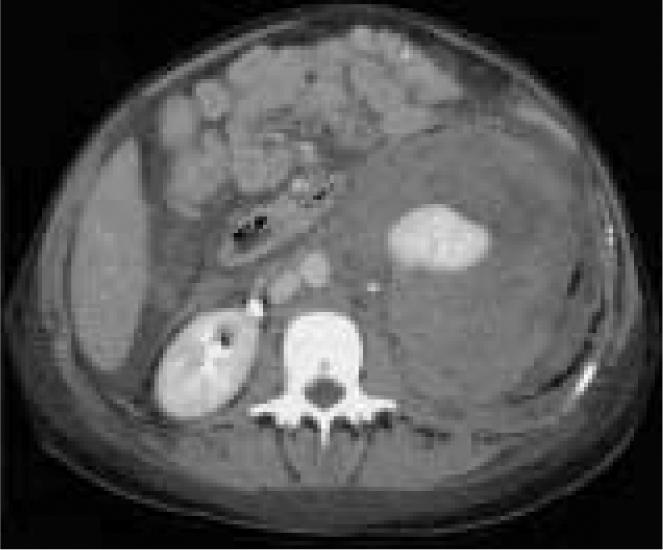

Pathologic studies of the patient’s kidney revealed patchy loss of the internal elastic lamina and medial smooth muscle of the interlobular arteries distal to the termination of the arcuate arteries (Figure 5). There was no evidence of neoplasm or infection. No other significant vascular abnormality was noted. The vascular changes were consistent with segmental arterial mediolysis (SAM).

Figure 5.

Pathology of the patient’s kidney revealed segmental arterial mediolysis, which is characterized by patch, non-circumferential loss of the media (A) and the external elastic lamina (B). Weakening of the media is exacerbated by focal vacuolization of this layer (C). Inflammation has been described in this condition sporadically and was seen in this patient (D).

Discussion

Wunderlich syndrome, also known as spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage (SRH) and spontaneous subcapsular hematoma, was first described in 1700 by Bonet and was more completely explained by Wunderlich in 1856.1 Although SRH is commonly associated with Lenk’s triad (acute flank pain, symptoms of internal bleeding, and tenderness to palpation), the most common signs and symptoms described are abdominal pain (67%), hematuria (40%), and shock (26.5%).2–4

SRH is a rare complication of several entities (Table 1). Tumors, particularly renal cell carcinoma and angiomyolipoma, are the most common cause of SRH, occurring in 57% to 73% of cases.3,4 The overall prevalence of SRH as a complication of tumors, however, is low. In renal cell carcinoma, it occurs in only 0.3% to 1.4% of cases,5–7 although the incidence is much higher in angiomyolipoma, occurring in 13% to 100% of cases, depending on tumor size.8–10 Adrenal myelolipoma, pheochromocytoma, and adrenal hemangiomas have also been reported to cause SRH.

Table 1.

Causes of Spontaneous Retroperitoneal Hemorrhage

|

Polyarteritis nodosa and non-neoplastic renal pathology such as nephritis are also common causes of SRH, with less common causes including Behçet disease, renal artery aneurysm rupture, cystic medial necrosis, blood dyscrasias, and arteriovenous malformations.1,3,11–23

One of the least common causes of SRH is SAM. First named segmental mediolytic arteritis by Slavin and Gonzalez-Vitale in 1979, SAM was found in 3 separate cases of hemorrhage, 2 of which involved a retroperitoneal component. The pathologic progression, which affected branches of the celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric arteries, was not consistent with known vasculitides or cystic medial necrosis.24 Instead, it was characterized by focal vacuolization of the media and internal elastic lamina involving only portions of the arterial circumference. Showing no predilection for vascular branch points as is found in other vasculitides, these lesions often had concomitant deposition of loose fibrous tissue, resulting in focal arterial weakening, aneurysm, dissecting hemorrhage, and rupture. Inflammation, eosinophilic infiltrates, and immunoglobulin complexes were not consistently found.25–27

Since the 1979 description, SAM has been identified in 3 discrete populations of patients. A 1949 report by Gruenwald28 and a 1979 paper by de Sa29 both describe several cases of necrosis in the coronary arteries of newborns consistent with SAM. Additionally, fewer than 10 more cases of SAM have been described in the cerebral arteries of young adults after stroke.30

Although SRH continues to be a rare clinical entity, its presence can be the indicator of a diverse set of pathologic conditions. While CT is now the gold standard for the diagnosis of retroperitoneal hemorrhage, several pathologic conditions may not be detected with CT and may require angiography.2,4,31,32 In the rare cases of SRH due to SAM, angiography may provide clues to diagnosis; however, pathologic examination remains the only definitive method of diagnosis.33

Main Points.

Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage can be caused by various pathologic conditions, including tumors or nephritis.

Although spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage is commonly associated with Lenk’s triad (acute flank pain, symptoms of internal bleeding, and tenderness to palpation), common signs and symptoms include pain, hematuria, and shock.

Computed tomography can miss segmental arterial mediolysis as a cause of spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage.

Angiography, with pathologic confirmation, facilitates the definitive diagnosis of segmental arterial mediolysis.

References

- 1.Polkey HJ, Vynalek WJ. Spontaneous nontraumatic perirenal and renal hematomas. Arch Surg. 1933;26:196. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolff JM, Jung PK, Adam G, Jakse G. Spontaneous retroperitoneal haemorrhage associated with renal disease. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1998;43:53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDougal WS, Kursh ED, Persky L. Spontaneous rupture of the kidney with perirenal hematoma. J Urol. 1975;114:181–184. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)66981-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgentaler A, Belville JS, Tumeh SS, et al. Rational approach to evaluation and management of spontaneous perirenal hemorrhage. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:121–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang S, Ma C, Lee S. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage from kidney causes. Eur Urol. 1988;15:281–284. doi: 10.1159/000473452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skinner D, Colvin RB, Vermillion CD, et al. Diagnosis and management of renal cell carcinoma: a clinical and pathological study of 309 cases. Cancer. 1971;28:1165–1177. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1971)28:5<1165::aid-cncr2820280513>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel NP, Lavengood RW. Renal cell carcinoma: natural history and results of treatment. J Urol. 1978;119:722–726. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)57611-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oesterling JE, Fishman EK, Goldman SM, Marshall FF. The management of renal angiomyolipoma. J Urol. 1986;135:1121–1124. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)46013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Baal JG, Smits NJ, Keeman JN, et al. The evolution of renal angiomyolipomas in patients with tuberous sclerosis. J Urol. 1994;152:35–38. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32809-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koh KB, George J. Radiological parameters of bleeding renal angiomyolipomas. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1996;30:265–268. doi: 10.3109/00365599609182303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tocci PE, Lankford RW, Lynne CM. Spontaneous rupture of the kidney secondary to polyarteritis nodosa. J Urol. 1975;113:860–863. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)59600-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smailowitz Z, Kaneti J, Sober I. Spontaneous perirenal hematoma: a complication of polyarteritis nodosa. J Urol. 1979;121:82–83. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)56671-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yonou H, Miyazato M, Sugaya K, et al. Simultaneous bilateral perirenal hematomas developing spontaneously in a patient with polyarteritis nodosa. J Urol. 1999;162:483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erdem Y, Oymak Q, Yalçin AU, et al. Spontaneous perirenal hematoma as a rare complication of polyarteritis nodosa. Nephron. 1995;69:491. doi: 10.1159/000188530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka K, Noguchi S, Shuin T, et al. Spontaneous rupture of adrenal pheochromocytoma: a case report. J Urol. 1994;151:120–121. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34886-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catalano O. Retroperitoneal hemorrhage due to a ruptured adrenal myelolipoma: a case report. Acta Radiol. 1996;37:688. doi: 10.1177/02841851960373P254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldman HB, Howard RC, Patterson AL. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage from a giant adrenal myelolipoma. J Urol. 1996;155:639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bishoff JT, Waguespack RL, Lynch SC, et al. Bilateral symptomatic adrenal myelolipoma. J Urol. 1997;158:1517–1518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trivedi R, Levy M, Ibrahim I, Bonacarti A. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage from a ruptured hypernephroma. J Surg Oncol. 1979;11:269–273. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930110313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLean PA, Wilson JD, Kelalis PP. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage associated with hypernephroma. J Urol. 1967;98:576–578. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)62935-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sueyoshi E, Sakamoto I, Hayashi N, et al. Ruptured renal artery aneurysm due to Behçet’s disease. Abdom Imaging. 1996;21:166–167. doi: 10.1007/s002619900036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang JC, Hye RJ. Ruptured renal artery aneurysm during pregnancy. Ann Vasc Surg. 1996;10:370–372. doi: 10.1007/BF02286782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubota J, Tsunemura M, Amano S, et al. Non-Marfan idiopathic medionecrosis (cystic medial necrosis) presenting with multiple visceral artery aneurysms and diffuse connective tissue fragility: two brothers. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1997;20:225–227. doi: 10.1007/s002709900143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slavin RE, Gonzalez-Vitale JC. Segmental mediolytic arteritis: a clinical pathologic study. Lab Invest. 1976;35(1):23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heritz DM, Butany J, Johnston KW, Sniderman KW. Intraabdominal hemorrhage as a result of segmental mediolytic arteritis of an omental artery: case report. J Vasc Surg. 1990;12:561–565. doi: 10.1067/mva.1990.24040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slavin RE, Cafferty L, Cartwright J. Segmental mediolytic arteritis: a clinicopathologic and ultrastructural study of two cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:558–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armas OA, Donovan DC. Segmental mediolytic arteritis involving hepatic arteries. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1992;116:531–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gruenwald P. Necrosis in the coronary arteries of newborn infants. Am Heart J. 1949;38:889–897. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(49)90889-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Sa DJ. Coronary arterial lesions and myocardial necrosis in stillbirths and infants. Arch Dis Child. 1979;54:918–930. doi: 10.1136/adc.54.12.918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leu HJ. Cerebrovascular accidents resulting from segmental mediolytic arteriopathy of the cerebral arteries in young adults. Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;2:350–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kendall AR, Senay BA, Coll ME. Spontaneous subcapsular renal hematoma: diagnosis and management. J Urol. 1988;139:246–250. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)42376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zagoria RJ, Dyer RB, Assimos DG, et al. Spontaneous perinephric hemorrhage: imaging and management. J Urol. 1991;145:468–471. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakano T, Morita K, Imaki M, Ueno H. Segmental arterial mediolysis studied by repeated angiography. Br J Radiol. 1997;70:656–658. doi: 10.1259/bjr.70.834.9227264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]