Abstract

Junctophilin (JP) mediates the close contact between cell surface and intracellular membranes in muscle cells ensuring efficient excitation-contraction coupling. Here we demonstrate that disruption of triad junction structure formed by the transverse tubular (TT) invagination of plasma membrane and terminal cisternae of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) by reduction of JP expression leads to defective Ca2+ homeostasis in muscle cells. Using adenovirus with small hairpin interference RNA (shRNA) against both JP1 and JP2 genes, we could achieve acute suppression of JPs in skeletal muscle fibers. The shRNA-treated muscles exhibit deformed triad junctions and reduced store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), which is likely due to uncoupled retrograde signaling from SR to TT. Knockdown of JP also causes a reduction in SR Ca2+ storage and altered caffeine-induced Ca2+ release, suggesting an orthograde regulation of the TT membrane on the SR Ca2+ release machinery. Our data demonstrate that JPs play an important role in controlling overall intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in muscle cells. We speculate that altered expression of JPs may underlie some of the phenotypic changes associated with certain muscle diseases and aging.

INTRODUCTION

Ca2+ acts as an important second messenger in many cellular signal transduction pathways. Two principle sources modulate Ca2+ homeostasis in the cell: channels in the plasma membrane (PM) that open to allow external Ca2+ to enter the cell, and internal stores sequestered in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) that release Ca2+ following diverse stimuli. Cross talk between extracellular Ca2+ entry and intracellular Ca2+ release is an essential mechanism to shape the dynamic aspects and spatial coordination of Ca2+ signaling (1,2). In striated muscle cells, the transverse tubular (TT) invagination of PM contacts the terminal cisternae of SR to form a triad junction, establishing a structural framework for external regulation of intracellular Ca2+ release (3).

Junctophilin (JP) is a unique protein that spans the junctional gap between TT and SR in muscle cells and mediates peripheral coupling between PM and ER in neuronal cells (4,5). In mammalian excitable cells, four JP subtypes derived from different genes have been identified: JP1—predominantly present in skeletal muscle, JP2—expressed in cardiac and other muscle cell types, and JP3 and JP4—mainly located in neuronal tissues (5). Genetic ablation of JP2 in mice increased the junctional gap distance in cardiomyocytes, resulting in reduced Ca2+ transients and embryonic lethality (4). Similarly, JP1 knockout mice exhibited skeletal muscles with deformed triad junctions and died shortly after birth (6).

Although these findings indicate the importance of JP2 in embryogenesis and JP1 in neonatal development, the lethality associated with germ-line ablation of either JP1 or JP2 prevents physiological evaluation of JPs in the maintenance of Ca2+ homeostasis in adult striated muscles. Indeed, this mirrors a prevalent challenge in aging studies as the function of essential genes, the absence of which would lead to embryonic lethality, cannot be studied in aging animals using conventional knockout approaches.

In this study, we used adenoviral-mediated delivery of small hairpin interference RNA (shRNA) against both JP1 and JP2 to skeletal muscle fibers in adult mice and examined the changes in junctional membrane structure resulting from acute knockdown of JP1 and JP2. Our results demonstrate that suppression of JP1 and JP2 in skeletal muscle leads to disruption of the triad junction structure, defective store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), reduced SR Ca2+ stores, and altered SR Ca2+ release in adult skeletal muscle fibers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

shRNA constructs

Initial screening experiments for RNAi probes to suppress JP1 and JP2 were conducted using several synthetic siRNA oligonucleotides targeting conserved regions between the mouse jp1 and jp2 cDNAs. Using JP1- and JP2-specific antibodies (4), Western blot analysis revealed one particular probe (as shown in Fig. 1 B) that was highly effective at silencing the expression of both JP1 and JP2. This probe was used for further studies by cloning synthesized oligonucleotides that targeted this conserved sequence in mouse jp1 (nt. 836–856) and jp2 (nt. 848–868) cDNAs: 5′-GATCCACCTACATGGGCGAGTGGATTCAAGAGATCCACTCG CCCATGTAGGTTTTTTCTCGAGG-3′ and 5′-AATTCCTCGAGAAAAAAACCTAC ATGGGCGAGTGGATCTCTTGAATCCACTCGCCCATGTAGGTG-3′ into various vectors. As a control, oligonucleotides targeting a specific sequence in the luciferase cDNA, 5′-GATCCGTGCGCTGCTGGTGCCAACTTCAAGAGATTTTTTGCTAGCG-3′, and 5′-AATTCGCTAGCAAAAAATCTCTTGAAGTTGGTACTAGCAACGCACG-3′, were also synthesized. These oligonucleotides were annealed to the BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites of the pSIREN-DNR plasmid (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) for synthesis of shRNA interference probes. In addition, the enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression cassette from pCMS-EGFP plasmid (Clontech) was inserted into the pSIREN-DNR vector, resulting in the generation of pU6-EGFP (shRNA) and pU6-EGFP (control) constructs. For viral packaging, a separate plasmid, pU6-dsRED(shRNA), was derived from the pShuttle vector (Clontech) by two subcloning steps. First, a red fluorescence protein (RFP) cDNA was inserted behind the cytomegalovirus promoter. Second, the U6-shRNA cassette from pSIREN-DNR was ligated into the pShuttle backbone. The SceI and I-CeuI restriction fragment from pU6-dsRED (shRNA) was then shuttled into the Adeno-X DNA vector (Clontech) to create the Ad-shRNA plasmid. Ad-shRNA virus was packaged and amplified in HEK 293 cells according to the manufacturer's protocol (Adeno-XTM expression system, Clontech). Control viruses were generated in an identical manner using the shRNA sequence-targeting luciferase.

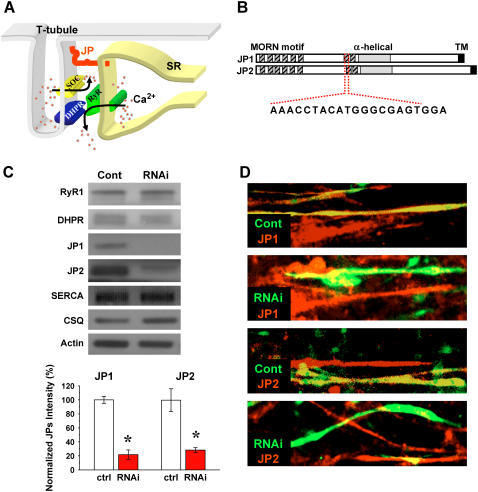

FIGURE 1.

JP and TT/SR coupling and shRNA-mediated suppression of JP in mammalian skeletal muscle. (A) JP is a unique protein that spans the junctional gap between TT invagination of cell surface membrane and terminal cisternae of SR in muscle cells. DHPR is represented in blue, RyR is shown in green, store-operated Ca2+ channel is shown in yellow, and JP is in red. (B) The functional motifs of JP are divided into three domains: a TM sequence inserted into the SR membrane, repeated “MORN” sequences that adhere to the TT membrane, and an α-helical-rich structure in the middle. The listed nucleotide sequence represents the siRNA target. (C) Western blot of JP1 and JP2 expression in siRNA oligonucleotide transfected C2C12 myotubes performed at day 5 after myotube differentiation, providing over 95% transfection efficiency. Controls represent muscles transfected with a scramble siRNA probe. p-values of ≤0.01 were considered as significant (same criteria in following figures). Normalized protein levels with actin show that shRNAs significantly knock down both JP1 and JP2 (lower panel, n = 5–8, p = 2.11529E-7 and 0.00358, respectively) but do not affect the expression of RyR1, DHPR, SERCA2, and CSQ in C2C12 myotubes. (D) Immunostaining of C2C12 myotubes transfected with the pU6-EGFP (with luciferase shRNA as control) and pU6-EGFP (shRNA), providing ∼30% transfection efficiency. Transfected cells are labeled with GFP, and red fluorescence represents staining of JP1 and JP2 with specific antibodies. Any yellow fluorescence in RNAi panels likely results from the presence of overlapping nontransfected myotubes in the cell layers. These pictures were representative of 16 experiments.

Gene transfection and viral infection

C2C12 myogenic cells, cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 10% horse serum, and penicillin-streptomycin supplement, were transfected with either pU6-EGFP (control) or pU6-EGFP (shRNA) plasmids using GeneJammer reagent (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Eight hours after transfection, the culture medium was changed to DMEM containing 2.5% horse serum to allow for differentiation into myotubes. At 4–5 days postdifferentiation, confocal imaging and immunostaining of individual myotubes were performed.

Viral-mediated delivery of shRNA into adult muscle fibers was achieved by two separate protocols. First, adult mice (C57BL/J6) were anesthetized with ketamine (200 mg/kg) and 2 × 108 plaque-forming unit (pfu) of either Ad-shRNA or Ad-control was injected into the flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscle. At 4–5 days postinjection, individual FDB muscle fibers were isolated for intracellular Ca2+ measurement and confocal imaging studies. Second, intact bundles of extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle were dissected from C57BL/J6 mice (5–7 weeks of age) and immediately infected with 2 × 108 pfu of Ad-shRNA or Ad-control viruses. The muscle fibers were cultured in DMEM with 2.5% horse serum for 5 days. Then, individual EDL muscle fibers were dissociated and mechanically skinned for confocal measurements of SOCE.

Muscle dissection and mechanical skinning

The procedures of muscle dissection and skinning were described in our previous studies (7). Intact EDL muscle fibers were infected with Ad-shRNA or Ad-control viruses and maintained in DMEM containing 2.5% horse serum for 3–5 days. Over this culture period, only muscle fibers that retained normal contractile functions as evidenced by an intact striation pattern as well as normal contractile properties were utilized. This culture period not only allows virus infection and shRNA-mediated gene expression knockdown, it also eliminates damaged fibers from being used in functional assays as minor damage introduced during the dissection step is amplified during the culturing period and leads to death of the muscle fiber.

Confocal microscopy for SOCE measurements

Viral-infected, isolated muscle fibers were mechanically skinned in the presence of an intracellular-like solution containing 500 μM Rhod-5N fluorescent Ca2+ indicator and a total [Ca2+] of 500 μM (7,8). The concomitant use of Rhod-5N and Ca2+ prevented contraction of muscle during the skinning procedure since Rhod-5N functions as a Ca2+ chelator, and ionized Ca2+ is essentially zero under these conditions. To measure SOCE, changes in Rhod-5N fluorescence trapped inside the TT membrane of skinned muscle fibers was monitored with a BioRad (Hercules, CA) Radiance2100 laser scanning confocal system attached to a Nikon (Tokyo, Japan) inverted microscope with 60×, numerical aperture 1.4 objective, and 543-nm HeNe laser. Priming and Ca2+ loading into the TT compartment were accomplished through 2 min exposure of skinned fibers to (in mM) 110 K-glutamate, 30 Na-glutamate, 6.5 MgCl2, 15 creatine phosphate, 5.0 ATP, 20 BES (2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]ethanesulfonic acid), 2.5 μg/ml creatine phosphokinase, pCa 7.0, pH 7.1. Loading of Ca2+ into SR was performed in a solution containing 140 K-methanesulfate, 6.5 MgCl2, 15 creatine phosphate, 5.0 ATP, 20 BES, 5.0 EGTA, 2.5 μg/ml creatine phosphokinase, pCa 6.6, pH 7.1. Depletion of the SR Ca2+ store, which leads to activation of SOCE was initiated through application of 30 mM caffeine and 20 μM thapsigargin (TG) in a solution containing 140 K-methanesulfate, 5.0 MgCl2, 5 creatine phosphate, 1.0 ATP, 20 BES, 3.0 EGTA, 7.0 BAPTA, pCa 8.5, pH 7.1. All solutions contained 5 μM carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy) phenyl hydrazone to specifically inhibit Ca2+ buffering by mitochondria.

Electron microscopy

Electron microscopy (EM) studies were performed following our published protocols (6). Briefly, skeletal muscles were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) and later postfixed in 1% OsO4 and 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). Microthin sections were double stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. These sections were examined under a transmission electron microscope (JEM-1010; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

Intracellular Ca2+ measurement

Confocal microscopy (BioRad Radiance2100) was used to resolve the spatial and temporal distribution of intracellular Ca2+ concentrations in individual muscle cells with a 488-nm Argon laser. FDB fibers were loaded with 10 μM Fluo-4-AM for 15 min, prepared in 2 mM Ca2+ balanced salt solution containing (in mM): 137 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES at pH 7.4. A field stimulation of 1 Hz was employed to induce Ca2+ release from the SR after cells were bathed in a solution containing 0 Ca2+. VICR was shown as ΔF/F0, F0 was the Fluo-4 signal without field stimulation. The recovery of VICR is represented by percentage of VICR (ΔF/F0) compared with VICR (ΔF/F0) before removal of extracellular Ca2+.

For quantitative measurements of intracellular [Ca2+], C2C12 myotubes at day 4 or 5 after differentiations or FDB muscle fibers were loaded with 5 μM Fura-2-AM. A dual-wavelength (excitation at 340 nm and 380 nm) PTI spectrofluorometer (Photon Technology International, Birmingham, NJ) was used to determine the kinetic changes of caffeine-induced intracellular Ca2+ transients (9). The ratio of F340 and F380 (emission at 510 nm) was used to represent [Ca2+]i.

Statistics

One-way analysis of variance using OriginPro 7.0 software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA) was performed for statistical analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all experiments, except for EM analyses where a p < 0.01 was required for statistical validation of data.

RESULTS

shRNA-mediated suppression of JP1 and JP2 in mammalian skeletal muscle

As shown in Fig. 1 A, JP contains a transmembrane (TM) sequence at the carboxyl-terminus that integrates into the SR membrane and repeated motifs that adhere to the TT membrane amino terminus. Between these domains, JP contains a high degree of α-helical structure that presumably provides elastic coupling between TT and SR membranes (Fig. 1 B). Based on Western blot analysis, it has been confirmed that both JP1 and JP2 are expressed in skeletal muscle (5). Systemic ablation of either JP1 or JP2 in mice results in embryonic or neonatal lethality (4,6).

To overcome the lethality associated with germ-line ablation of JP and to examine the effects of acute knockdown of JP in adult muscle fibers, we used RNA interference to suppress the expression of both JP1 and JP2 in individual muscle cells. A small interference RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotide probe against a specific cDNA sequence shared by JP1 (nt. 836–856) and JP2 (nt. 848–868) was found to be highly effective in knocking down the expression of both JP1 and JP2 in cultured C2C12 skeletal myotubes (Fig. 1 C). JP1 and JP2 expression levels in differentiated C2C12 myotubes was reduced to 22% and 29%, respectively, of the level observed in myotubes transfected with control siRNA. Specificity of this probe to JP1 and JP2 was confirmed by establishing that no significant changes in expression levels of major Ca2+ regulatory proteins, including calsequestrin (CSQ), ryanodine receptor (RyR), dihydropyridine receptor (DHPR), and SR Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) was detected in C2C12 cells treated with the JP siRNA oligonucleotide.

Immunostaining of C2C12 myotubes transfected with plasmid coding for a shRNA targeting the same position as the siRNA oligonucleotide on JP1 and JP2 revealed extensive downregulation of both JP1 and JP2 (Fig. 1 D). Transfected cells were identified by the green fluorescence of GFP, and red fluorescence indicates staining for JP1 and JP2 with specific antibodies. Cells transfected with the control shRNA showed yellow signal, representing coexpressing patterns of green and red fluorescence, whereas those transfected with the specific shRNA plasmid showed only green signal, demonstrating the absence of red fluorescent staining for both JP1 and JP2. Due to the low efficiency (∼30%) of liposome-mediated transfection of plasmids of pU6-EGFP (control) and pU6-EGFP (shRNA), C2C12 cells positive for red fluorescence labeling alone represent those cells that are not transfected with plasmid. However, in the following functional measurements in C2C12 myotubes, we could select transfected cells using GFP as a marker.

Uncoupled SOCE activation and reduced intracellular Ca2+ release in C2C12 cells after silencing of JP1 and JP2

C2C12 myotubes contain abundant SOCE that can be activated upon depletion of SR Ca2+ stores (9,10). We used 20 μM TG to completely deplete SR Ca2+ (Fig. 2 A, left). TG-sensitive SR Ca2+ stores in myotubes transfected with shRNA against JPs comprised ∼60% of the Ca2+ stores in control myotubes (Fig. 2 A, right). Quenching of intracellular Fura-2 fluorescence by the entry of extracellular Mn2+ (0.5 mM) via store-operated Ca2+ channel reveals graded and sigmoidal activation of SOCE in C2C12 myotubes transfected with control plasmids (Fig. 2 B). Clearly, operation of SOCE in shRNA-treated C2C12 myotubes was altered as the sigmoidal phase of Fura-2 quenching by Mn2+ was completely abolished.

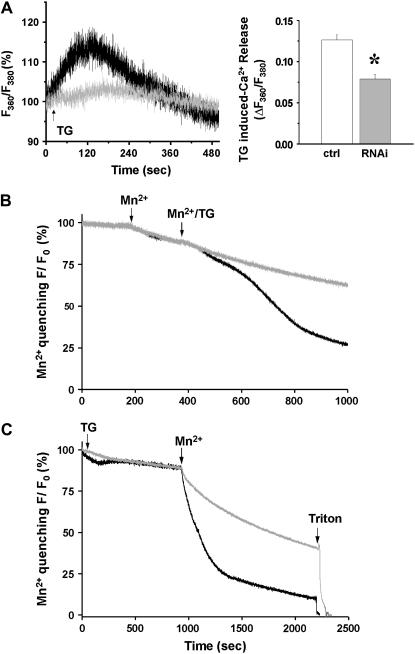

FIGURE 2.

Uncoupled SOCE activation in C2C12 cells after silencing of JP1 and JP2. (A) Representative traces of percentage changes in ratio of fluorescence at excitation of 360 and 380 show that addition of 20 μM TG (arrow) induced passive Ca2+ release from SR Ca2+ stores (left panel). In JP shRNA-treated C2C12 myotubes (gray, n = 4), SR Ca2+ stores are significantly less than that in myotubes transfected with pU6-EGFP-control plasmids (black, n = 5) indicated by reduced TG-releasable Ca2+ (right panel). (B) Quenching of intracellular Fura-2 fluorescence by the entry of extracellular Mn2+ (0.5 mM) reveals graded and sigmoidal activation of SOCE in C2C12 myotubes transfected with control plasmids (black, n = 5). In JP shRNA-treated C2C12 myotubes (gray) the sigmoidal phase of Fura-2 quenching by Mn2+ was completely absent, indicating defective SOCE (n = 4). (C) To examine the changes in the maximum degree of SOCE activation, C2C12 cells were incubated with TG for an extended period of time to ensure complete depletion of their SR Ca2+ stores. Compared with the control (n = 4, maximum quenching rate is −9.96 ± 0.88%/min), the maximum activation of SOCE was reduced in siRNA-transfected C2C12 myotubes (n = 5, maximum quenching rate is −4.99 ± 1.40%/min) by ∼50%. p < 0.005.

To examine the changes in the maximum degree of SOCE activation, C2C12 cells were incubated with TG for an extended period of time to ensure complete depletion of their SR Ca2+ stores. Under these conditions, addition of Mn2+ to the extracellular solution resulted in rapid and linear quenching of Fura-2 fluorescence in C2C12 cells transfected with the control plasmid. Compared with the control, the maximum activation of SOCE was significantly reduced in siRNA-transfected C2C12 myotubes (Fig. 2 C).

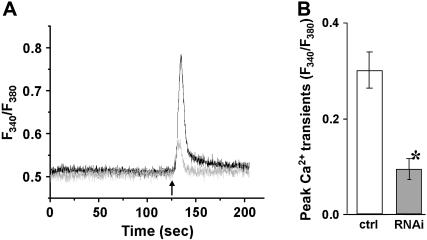

Next we used caffeine, an agonist of the RyR Ca2+ channel, to investigate how acute downregulation of JPs alters SR Ca2+ release in C2C12 myotubes. As shown in Fig. 3 A, C2C12 myotubes transfected with control plasmids responded with rapid caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients with a sharp decaying phase (n = 19). In contrast, myotubes transfected with the shRNA plasmid displayed significantly reduced Ca2+ transient amplitude (n = 15) (Fig. 3 B).

FIGURE 3.

Reduced caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in C2C12 cells after silencing of JP1 and JP2. C2C12 myotubes transfected with pU6-EGFP-shRNA (gray) or pU6-EGFP-control (black) were loaded with 5 μM Fura-2-AM. Individual transfected cells were selected for Ca2+ measurements by the presence of a GFP marker. (A) A total of 10 mM caffeine was added to the extracellular solution without Ca2+, indicated by an arrow. Cells transfected with the shRNA plasmid displayed a smaller amplitude in caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients than in control cells. (B) The difference in peak amplitude of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients is statistically significant between the control and shRNA-treated C2C12 myotubes (n ≥ 15, p < 0.01). Data are presented as mean ± SE.

Disrupted triad junction structure in adult skeletal muscle fibers with acute suppression of JP1 and JP2

Packaging of shRNA sequence into adenovirus enabled direct examination of the changes in membrane architecture associated with JP suppression in adult muscle fibers. For this purpose, FDB muscles in living mice were injected with the Ad-shRNA specific for JP1 and JP2 or Ad-control with RFP as marker. As shown in Fig. 4, A and B, 4 days after infection of the FDB muscle, significant downregulation of JP1 and JP2 could be detected by Western blot of whole muscle extracts. The lesser degree of JP1 and JP2 suppression in FDB muscle compared with C2C12 myotubes likely reflects the mosaic effect of Ad-shRNA infection following injection into anatomical muscles (Fig. 4 A).

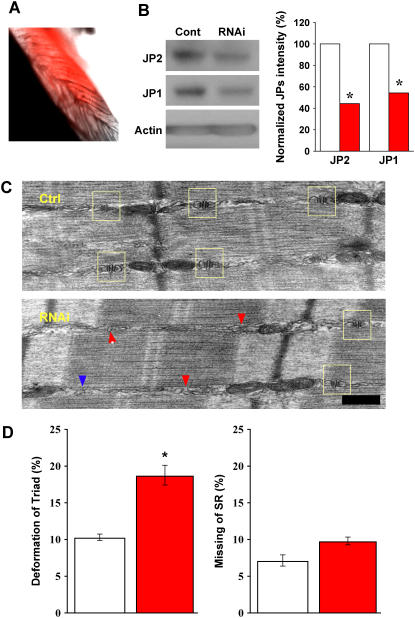

FIGURE 4.

Suppression of JP1 and JP2 leads to defective triad junction in skeletal muscle. (A) A typical sample of FDB muscle infected with adenovirus packaged with shRNA against JP1 and JP2, taken 4 days postinjection of virus. Red color represents RFP fluorescence, indicating infected fibers. (B) Western blot of JP1 and JP2 expression in skeletal muscle fibers, 4 days postinfection with adenoviruses packaged with nonspecific shRNA (control) and specific shRNA against JP1 and JP2 (RNAi). Similar to results in C2C12 cells, normalized protein levels with actin show that shRNAs significantly knock down both JP1 and JP2. (C) Defective triad junction in skeletal muscle, examined by EM. Top panel shows a typical muscle fiber from the Ad-cont-infected mice, and the bottom panel shows a typical muscle fiber from the Ad-shRNA-infected mice. Scale bar indicates 0.2 μm. The sides of A-I junctional regions of myofibrils where triads are expected to be present were observed. In the case where normal paired triad junctions (yellow box) flanking each Z-disk could not be observed by eye, such regions were assigned “deformed triad”. TT and SR without coupling were seen in the “deformed triad”, and such membrane structures were not seen very frequently at the regions analyzed (<20% in all counted). Muscle infected with Ad-cont resembles wild-type, with normal SR/TT/SR architecture (yellow box), whereas in Ad-shRNA-infected muscle triad junctions are frequently deformed (red arrow) or missing (blue arrow). (D) Bar graph shows the summarized data obtained from the EM analyses of more than 1000 A-I junctional regions from 11 muscle specimens obtained from 6 different animals. p = 0.00381 (left panel) and 0.0453 (right panel). To insure accuracy in morphological assessment, we increased stringency for statistical significance. p-value <0.01 was considered statistical significance. Data presented as mean ± SE.

The periphery of A-I junctional regions of myofibrils where triads are expected to be present were analyzed by EM, which revealed altered triad structures in FDB muscles infected with Ad-shRNA (Fig. 4 C). The regions, where normal alignment of SR/TT/SR could not be observed at individual myofibrils, were termed “deformed triads”. For statistical analysis, 11 muscle specimens from six mice were prepared, and 100–130 A-I junctional regions per preparation were examined (Fig. 4 E). Due to the heterogeneity of membrane structure in FDB muscle, two parameters were used in this analysis: a) regions with deformed triad junction, and b) regions with missing triad junction. As shown in Fig. 4 D, the number of deformed triad junctions was significantly higher in Ad-shRNA-infected muscles as compared to those infected with Ad-control (p < 0.005). In addition, the percentage of missing triads in Ad-shRNA-infected FDB muscle increased; however, this difference did not achieve our stringent threshold for statistical significance (p = 0.0453).

Uncoupling of SOCE in adult muscle fibers infected with shRNA for JP1 and JP2

Structural changes in triad junctions apparently led to changes in adult muscle cell Ca2+ homeostasis similar to those seen with JP suppression in C2C12 myotubes. We tested if downregulation of JPs could affect the function of SOCE using a skinned EDL muscle fiber preparation (7). To allow acute suppression of JP in individually isolated EDL muscle fibers, these fibers must be cultured for up to 5 days before skinning to allow for adenoviral infection and JP suppression. Under our experimental conditions, fibers cultured for 3–5 days maintained normal contractile function in response to voltage stimulation (Fig. 5 A). Mechanical skinning of these cultured fibers did not disrupt the contractile apparatus, as evidenced by the normal force versus pCa relationship displayed by these preparations (Fig. 5 B). High-resolution confocal imaging of Rhod-5N fluorescence reveals the expected doublet pattern of the TT membrane, suggesting the integrity of membrane structures is maintained and illustrating the specificity of dye loading into TT (Fig. 5 C). EDL muscle fibers infected with Ad-control virus showed comparable contraction with normal fibers when the fibers were treated with caffeine in solution without high concentration of EGTA and BAPTA to buffer Ca2+, suggesting that virus infection alone did not affect the fibers contractility. To confirm that Rhod-5N is localized to the TT compartment, we treated the skinned fibers with saponin, which led to complete loss of fluorescence (Fig. 5 D), indicating not only proper dye compartmentalization but also absence of cross loading with other subcellular organelles.

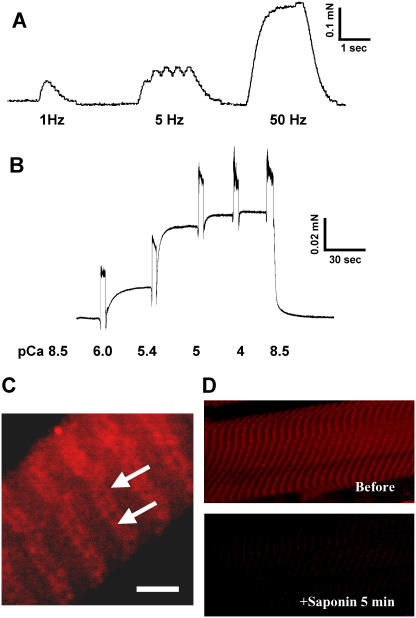

FIGURE 5.

Cultured skeletal muscle fibers maintain structural and functional integrity. (A) An intact EDL muscle fiber after culturing for 4 days was mounted onto an optoelectric force transducer as previously described (7,25). Presented trace is force produced upon electrical stimulation at 1, 5, and 50 Hz. (B) Cultured EDL fibers were permeabilized with Triton X-100. Ca2+-activated contractile force was measured at indicated pCa. Secondary upward inflections in the force tracings are mechanical artifacts of transferring a fiber between chambers with different pCa conditions. (C) Confocal imaging of Rhod-5N trapped inside the sealed TT membranes. Arrows indicate the doublet pattern in TT membranes typical of mammalian skeletal muscle. Similar results were obtained in at least three experiments. Scale bar represents 5 μm. (D) To confirm dye localization and the absence of cross loading of TT and SR, fiber was exposed for 5 min to a relaxing solution containing 50 μg/ml saponin, which only hyperpermeabilizes the sarcolemma, leaving the SR intact. Fluorescence levels in saponin-treated fibers decreased to levels comparable to background levels, suggesting that Rhod-5N was primarily localized in the TT.

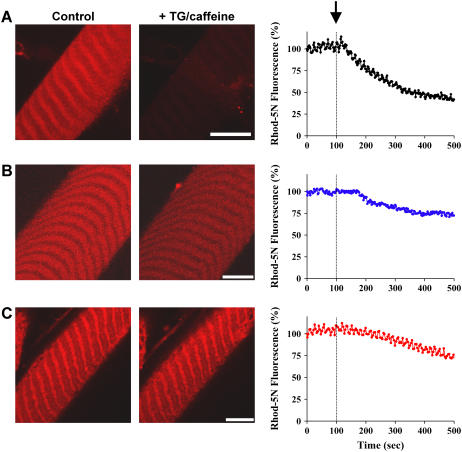

As shown in Fig. 6 A, treatment of the skinned muscle fiber with TG and caffeine leads to a time-dependent activation of SOCE and an efflux of Ca2+ across the TT membrane, as indicated by the decrease in fluorescence of Rhod-5N trapped inside the TT compartment. The delay interval of <60 s between the start of SR depletion and the onset of Ca2+ efflux from the TT is consistent with the time required for TG to fully block the SERCA pump and, in combination with caffeine, cause the depletion of SR Ca2+. Ca2+ efflux from the TT caused a decrease of Rhod-5N fluorescence that was not influenced by nifedipine, a known antagonist of the L-type Ca2+ channel (not shown). Instead, it was inhibited by 2-amino ethyoxyldiphenyl borate (2-APB, 50 μM), a known blocker of SOCE (11) (Fig. 6 B). Suppression of JP1 and JP2 expression in skinned muscle fibers leads to a remarkable uncoupling of SOCE, as shown by the maintenance of TT Rhod-5N fluorescence after exposure to TG and caffeine (Fig. 6 C), which indicates that Ca2+ remains trapped in the TT. These results in adult muscle fibers are similar to those shown in Fig. 2, where silencing of JP1 and JP2 results in a loss of graded activation of SOCE in C2C12 myotubes.

FIGURE 6.

Uncoupling of SOCE in skeletal muscle infected with shRNA for JP1 and JP2. (A) Time-dependent changes of Rhod-5N fluorescence in skinned EDL fibers infected with Ad-control viruses were monitored using a confocal microscope after addition of 20 μM TG and 30 mM caffeine (marked by arrow). Gradual decrease in Rhod-5N fluorescence indicates SOCE activity (n = 9). (B) Preincubation of the skinned muscle fiber (treated with Ad-control) with 50 μM 2-APB significantly prevented the decrease of Rhod-5N fluorescence after the addition of TG and caffeine (n = 9). (C) Viral-mediated delivery of the shRNA for JP1 and JP2 into the EDL muscle fiber resulted in uncoupling of SOCE in the skinned muscle preparation. The TG- and caffeine-triggered decrease of Rhod-5N fluorescence was significantly less in the Ad-shRNA-infected muscle fiber (n = 8). Traces on the right are mean values for the indicated number of experiments per condition. The scale bars represent 5 μm for all images.

Abnormal maintenance of intracellular Ca2+ storage in adult muscle fiber with suppression of JP1 and JP2

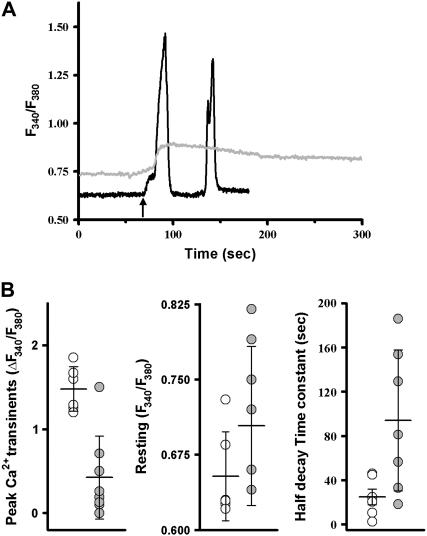

Similar to the results seen in C2C12 myotubes, downregulation of JP1 and JP2 also leads to abnormal caffeine-induced Ca2+ release across the SR membrane in intact skeletal muscle (Fig. 7). A diminished caffeine-induced SR Ca2+ transient in the shRNA-treated muscle fibers suggests that the storage of Ca2+ inside the SR was reduced (Fig. 7 A). This is also suggested by decreased Ca2+ stores observed in C2C12 myotubes transfected with JP shRNA, as measured by TG application (Fig. 2 A). Furthermore, reduced expression of JP1 and JP2 resulted in elevated levels of resting cytosolic [Ca2+] and prolongation of caffeine-induced Ca2+ release (Fig. 7 B).

FIGURE 7.

Altered CICR activity in skeletal muscle with suppression of JP1 and JP2. (A) Viral-infected, enzymatically dissociated FDB muscles were loaded with 5 μM Fura-2-AM. A total of 10 mM caffeine was added to the extracellular solution containing 0 [Ca2+] (arrow). Fibers infected with Ad-control virus (black) responded with rapid caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients with a sharp decaying phase. Occasionally, a second spontaneous Ca2+ transient occurred in the presence of caffeine, probably reflecting contraction induced in the continuous exposure to caffeine. Fibers infected with Ad-shRNA virus (gray) displayed elevated resting cytosolic [Ca2+] as well as smaller and prolonged caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients. (B) Averaged data from multiple experiments. Open circles (Ad-control) or solid circles (Ad-shRNA) represent individual fibers, horizontal bar represents the mean, and error bars are one standard deviation (n = 7–12); p-values for peak Ca2+ transient, half decay time, and resting Ca2+ are 0.0001, 0.03, and 0.00153, respectively. Statistical outliers (2 ± SD as cutoff value) were excluded.

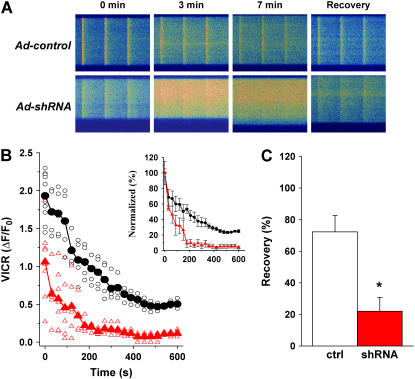

To investigate the effects of JP1 and JP2 knockdown on voltage-induced Ca2+ release (VICR), we repetitively stimulated (1 Hz) muscle fibers loaded with Fluo-4 in a Ca2+-free solution. This led to a progressive loss of Ca2+ from SR, with eventual depletion of SR Ca2+ stores occurring within 10 min in muscle fibers infected with the control shRNA (Fig. 8 A). In contrast, the JP-specific shRNA-treated muscle fibers lost their SR Ca2+ content significantly faster upon removal of extracellular Ca2+. For example, at 3 min after changing the extracellular [Ca2+] from 2 mM to 0 mM, ∼50% of VICR remained in the control muscle, whereas VICR dramatically reduced to <10% in shRNA-treated muscle (Fig. 8 B). At 7 min, VICR cannot be detected in the shRNA-treated muscle, although progressive elevation of resting cytosolic [Ca2+] and enhanced spreading of the Ca2+ wave became evident in the shRNA-treated muscle fibers following repetitive voltage stimulation, indicating that silencing of JP genes may lead to uncontrolled function of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) in skeletal muscle.

FIGURE 8.

Abnormal maintenance of intracellular Ca2+ storage in skeletal muscle with suppression of JP1 and JP2. (A) Confocal line scan measurement of voltage-induced Ca2+ transients in viral-infected FDB muscle cells (loaded with 10 μM Fluo-4-AM). Time elapsed from the removal of extracellular Ca2+ is indicated. Changes in the transverse dimension of the confocal image are due to variations in fiber shape at different line scan positions. (B) Decline of VICR with time in 0 [Ca2+]o is averaged from multiple experiments (n = 5 for Ad-control, n = 7 for Ad-shRNA). Circles represent individual Ad-control fibers (black); triangles represent Ad-shRNA fibers (red). Normalized VICR with VICR at time 0 is replotted to demonstrate the depletion rate of SR Ca2+ stores (inset panel). (C) After field-stimulated depletion of SR Ca2+ content, 2 mM Ca2+ was restored to the extracellular solution. The recovery of VICR was measured 20 min later (n = 8 for Ad-control; n = 7 for Ad-shRNA). Increasing the recovery time to 35 min did not significantly influence the response in Ad-shRNA muscle fibers. Data are presented as the mean with error bars representing one standard deviation, p < 0.001.

Although prolonged exposure of the muscle fiber to a Ca2+-free solution results in Ca2+ homeostasis changes that result in depletion of SR Ca2+ storage, the SR can be replenished through addition of Ca2+ to the extracellular solution. More than 70% recovery of VICR was observed with the control muscle 20 min after addition of 2 mM Ca2+ to the extracellular solution (Fig. 8 C). Further studies showed that the SR depletion-refilling process is reversible and repeatable with the control muscle (n = 14). However, only partial recovery of VICR was observed in the shRNA-treated muscle fibers, even after extended (>35 min) exposure to 2 mM Ca2+. This result is consistent with the defective SOCE mechanism as shown in Fig. 6.

DISCUSSION

Our studies reveal that JP is essential for the maintenance TT/SR junctional structures and thus participates in the maintenance of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, allowing growth and survival of muscle cells. Partial suppression of JP1 and JP2 is accompanied by reduced SOCE in skeletal muscle. The disruption of TT/SR structure as a result of suppression of JP1 and JP2 demonstrates that retrograde signaling from SR to TT is important in the activation of SOCE. This could either involve a diffusible second messenger (12,13) or require direct interaction between protein components on the TT and SR membranes (9,14). Knockdown of JP1 and JP2 also reduced SR Ca2+ stores, which could be due to compromised SOCE preventing replenishment of intracellular Ca2+ stores and/or increased leakage of the SR Ca2+ pool—the latter supported by our findings of altered caffeine-induced Ca2+ release. Although reduced amplitude of caffeine-induced Ca2+ release was consistent with reduced SR Ca2+ stores, the intriguing observation of prolonged decay time in Ca2+ transient in adult FDB muscles suggested either enhancement of CICR or impaired SERCA Ca2+ uptake in muscles with suppression of JP1 and JP2. Although here we cannot distinguish the two mechanisms, it is likely that abnormal CICR is a contributor since uncoupling of TT and SR membranes by JP1 and JP2 suppression may lead to the loss of an orthograde inhibitory function of the TT membrane on RyR channel activity. In fact, such an inhibitory relationship between these intimately apposed membrane structures has been previously suggested (15,16). It is noteworthy to mention that prolongation of Ca2+ transients observed in adult FDB muscles was not significant in C2C12 myotubes treated with shRNA against JPs. Although we cannot precisely pinpoint the mechanisms for this difference, we speculate that either the stage of triad maturation or other developmental issues related to C2C12 myotubes as compared to adult muscles likely played a role in producing such differences.

Our parallel studies in cultured C2C12 myotubes and freshly isolated FDB muscle fibers, as well as primary EDL muscle fibers maintained in culture, provide a systematic approach to evaluate the role of JP in intracellular Ca2+ signaling. Using C2C12 cells, we were able to rapidly screen for highly effective RNAi probes that target multiple JP isoforms. Using GFP or RFP as markers we were able to select individual muscle cells affected by JP suppression during our functional assays. During the course of our studies, we were able to maintain the contractile and structural integrity of cultured muscle fibers for an extended period to allow adenoviral-mediated RNAi repression of JP expression. In addition, the extension of the skinned muscle fiber preparation from amphibian (8) to mammalian muscle fibers provides us an ex vivo method to directly test the role of JPs in regulating the function of SOCE.

In our studies of triad membrane structure, we observed fewer disrupted triad junctions than we expected considering the dramatic changes in SOCE and CICR observed with JP suppression. There are intrinsic factors in these experiments that may contribute to the limited extent of triad junction disruption detected by EM. The lower efficiency of JP1 and JP2 suppression in adult muscle fibers probably reflects the localized effect of shRNA infection, as well as the nonlinear correlation between protein suppression and muscle function observed in numerous biological systems (17–19).

During the Ca2+ measurement assays, transfected C2C12 cells or infected muscle fibers can be selected by fluorescent markers; however, such selection of infected fibers is not viable in EM sections. Notice that the measurements of VICR and CICR in shRNA-treated muscle fibers are relatively variable, with some fibers exhibiting complete abolishment of CICR, whereas in others the reduction is much less. This probably reflects a variable degree of JP suppression in the individual muscle fibers, a finding that reinforces the physiological importance of a normal JP expression for maintenance of a health status in skeletal muscle cells.

Chronically dysfunctional CICR activity and/or impaired SR Ca2+ uptake could lead to an elevated intracellular Ca2+ level, which may underlie some of the phenotypic changes associated with muscular dystrophies, muscle fatigue, heart failure, neurodegeneration, and other human diseases (20–22). Mutations in JP3, the brain isoform of JP, are linked to Huntington disease (23). JP2 has been reported to be downregulated in hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathic mouse models (24). Recent data from our laboratory have suggested that altered expression of JP2 and JP1 is associated with heart failure and muscle aging (N.Weisleder, J. Ma, and Z. Pan, unpublished data). Therefore, understanding the mechanisms of JP modulation of Ca2+ signaling should provide important insights not only into the molecular understanding of the E-C coupling machinery, but also into therapies for human diseases. Although the lethality associated with germ-line ablation of JP1 and JP2 has complicated the study of the cell biological and physiological functions of JPs in animal models, our studies presented here demonstrate the potential of knocking down the expression of JPs using specific shRNA probes. In principle, one could extend this methodology to an in vivo animal model using regulated, tissue-specific expression of shRNA probes to modulate the expression of JPs in the heart, muscle, and neurons. Such an animal model should be valuable to investigate the regulation and adaptation processes of Ca2+ signaling in the pathophysiology of human diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jerome Parness and Clara Franzini-Armstrong for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by a UMDNJ foundation grant to Z.P., National Institutes of Health grants (RO1-AG15556, RO1-HL69000, RO1-CA95739, and RO1-DK51770) to J.M., an American Heart Association scientist development grant and a National Institutes of Aging faculty development grant to M.B., and an American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship to N.W.

Yutaka Hirata and Marco Brotto contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Dirksen, R. T. 2002. Bi-directional coupling between dihydropyridine receptors and ryanodine receptors. Front. Biosci. 7:d659–d670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ma, J., and Z. Pan. 2003. Junctional membrane structure and store operated calcium entry in muscle cells. Front. Biosci. 8:d242–d255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franzini-Armstrong, C., and A. O. Jorgensen. 1994. Structure and development of E-C coupling units in skeletal muscle. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 56:509–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeshima, H., S. Komazaki, M. Nishi, M. Iino, and K. Kangawa. 2000. Junctophilins: a novel family of junctional membrane complex proteins. Mol. Cell. 6:11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishi, M., H. Sakagami, S. Komazaki, H. Kondo, and H. Takeshima. 2003. Coexpression of junctophilin type 3 and type 4 in brain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 118:102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito, K., S. Komazaki, K. Sasamoto, M. Yoshida, M. Nishi, K. Kitamura, and H. Takeshima. 2001. Deficiency of triad junction and contraction in mutant skeletal muscle lacking junctophilin type 1. J. Cell Biol. 154:1059–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao, X., M. Yoshida, L. Brotto, H. Takeshima, N. Weisleder, Y. Hirata, T. M. Nosek, J. Ma, and M. Brotto. 2005. Enhanced resistance to fatigue and altered calcium handling properties of sarcalumenin knockout mice. Physiol. Genomics. 23:72–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Launikonis, B. S., M. Barnes, and D. G. Stephenson. 2003. Identification of the coupling between skeletal muscle store-operated Ca2+ entry and the inositol trisphosphate receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:2941–2944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan, Z., D. Yang, R. Y. Nagaraj, T. A. Nosek, M. Nishi, H. Takeshima, H. Cheng, and J. Ma. 2002. Dysfunction of store-operated calcium channel in muscle cells lacking mg29. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:379–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin, D. W., Z. Pan, E. K. Kim, J. M. Lee, M. B. Bhat, J. Parness, D. H. Kim, and J. Ma. 2003. A retrograde signal from calsequestrin for the regulation of store-operated Ca2+ entry in skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 278:3286–3292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bootman, M. D., T. J. Collins, L. Mackenzie, H. L. Roderick, M. J. Berridge, and C. M. Peppiatt. 2002. 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) is a reliable blocker of store-operated Ca2+ entry but an inconsistent inhibitor of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release. FASEB J. 16:1145–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Randriamampita, C., and R. Y. Tsien. 1993. Emptying of intracellular Ca2+ stores releases a novel small messenger that stimulates Ca2+ influx. Nature. 364:809–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smani, T., S. I. Zakharov, P. Csutora, E. Leno, E. S. Trepakova, and V. M. Bolotina. 2004. A novel mechanism for the store-operated calcium influx pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiselyov, K. I., D. M. Shin, Y. Wang, I. N. Pessah, P. D. Allen, and S. Muallem. 2000. Gating of store-operated channels by conformational coupling to ryanodine receptors. Mol. Cell. 6:421–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suda, N., and R. Penner. 1994. Membrane repolarization stops caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in skeletal muscle cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:5725–5729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, E. H., J. R. Lopez, J. Li, F. Protasi, I. N. Pessah, D. H. Kim, and P. D. Allen. 2004. Conformational coupling of DHPR and RyR1 in skeletal myotubes is influenced by long-range allosterism: evidence for a negative regulatory module. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286:C179–C189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy, A. M., H. Kogler, and E. Marban. 2000. A mouse model of myocardial stunning. Mol. Med. Today. 6:330–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy, A. M., H. Kogler, D. Georgakopoulos, J. L. McDonough, D. A. Kass, J. E. Van Eyk, and E. Marban. 2000. Transgenic mouse model of stunned myocardium. Science. 287:488–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao, W. D., D. Atar, Y. Liu, N. G. Perez, A. M. Murphy, and E. Marban. 1997. Role of troponin I proteolysis in the pathogenesis of stunned myocardium. Circ. Res. 80:393–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisner, D. A., and A. W. Trafford. 2002. Heart failure and the ryanodine receptor: does Occam's razor rule? Circ. Res. 91:979–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takagi, A., S. Kojima, M. Ida, and M. Araki. 1992. Increased leakage of calcium ion from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of the mdx mouse. J. Neurol. Sci. 110:160–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fong, P. Y., P. R. Turner, W. F. Denetclaw, and R. A. Steinhardt. 1990. Increased activity of calcium leak channels in myotubes of Duchenne human and mdx mouse origin. Science. 250:673–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes, S. E., E. O'Hearn, A. Rosenblatt, C. Callahan, H. S. Hwang, R. G. Ingersoll-Ashworth, A. Fleisher, G. Stevanin, A. Brice, N. T. Potter, C. A. Ross, and R. L. Margolis. 2001. A repeat expansion in the gene encoding junctophilin-3 is associated with Huntington disease-like 2. Nat. Genet. 29:377–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minamisawa, S., J. Oshikawa, H. Takeshima, M. Hoshijima, Y. Wang, K. R. Chien, Y. Ishikawa, and R. Matsuoka. 2004. Junctophilin type 2 is associated with caveolin-3 and is down-regulated in the hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 325:852–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brotto, M. A., and T. M. Nosek. 1996. Hydrogen peroxide disrupts Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of rat skeletal muscle fibers. J. Appl. Physiol. 81:731–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]