Abstract

We report investigations of the morphology and molecular structure of amyloid fibrils comprised of residues 10–40 of the Alzheimer's β-amyloid peptide (Aβ10–40), prepared under various solution conditions and degrees of agitation. Omission of residues 1–9 from the full-length Alzheimer's β-amyloid peptide (Aβ1–40) did not prevent the peptide from forming amyloid fibrils or eliminate fibril polymorphism. These results are consistent with residues 1–9 being disordered in Aβ1–40 fibrils, and show that fibril polymorphism is not a consequence of disorder in residues 1–9. Fibril morphology was analyzed by atomic force and electron microscopy, and secondary structure and inter-side-chain proximity were probed using solid-state NMR. Aβ1–40 fibrils were found to be structurally compatible with Aβ10–40: Aβ1–40 fibril fragments were used to seed the growth of Aβ10–40 fibrils, with propagation of fibril morphology and molecular structure. In addition, comparison of lyophilized and hydrated fibril samples revealed no effect of hydration on molecular structure, indicating that Aβ10–40 fibrils are unlikely to contain bulk water.

INTRODUCTION

Amyloid fibrils are filamentous protein aggregates that can be formed by a large and diverse class of polypeptides (1–3). Deposition of amyloid fibrils occurs in >20 diseases (4,5), including several that are major public health problems, such as Alzheimer's disease, type 2 diabetes, Parkinson's disease, and transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Amyloid fibrils are distinguished from other types of protein fibrils by the presence of a cross-β structural motif, established by x-ray fiber diffraction (4). Other aspects of the molecular structures of amyloid fibrils have been largely mysterious until recent studies using solid-state NMR (6–12), electron paramagnetic resonance (13–15), hydrogen exchange (16–18), and biochemical methods (19–21). Data from these techniques have been used to develop experimentally based structural models for amyloid fibrils (8,10,18,20,22–24), including fibrils formed by the 40-residue β-amyloid peptide associated with Alzheimer's disease (Aβ1–40) (8,20).

It has been demonstrated by electron microscopy (EM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) that a single peptide or protein can form amyloid fibrils with several distinct morphologies (25–27). Recent solid-state NMR and EM studies of Aβ1–40 fibrils have shown that different morphologies have somewhat different underlying molecular structures, that the morphology and molecular structure can be controlled by subtle variations in fibril growth conditions (at fixed temperature, buffer conditions, and peptide concentration), and that both the fibril morphology and the molecular structure are self-propagating when fibrils are grown from preexisting seeds (9). Structural and morphological variability is most likely the molecular basis for the phenomenon of strains in prion diseases (19,28–31), and may play a role in amyloid diseases (9). It seems likely that different fibril morphologies result from different fibril nucleation events, with particular growth conditions capable of favoring one nucleation event and its subsequent propagation. A detailed understanding of the influence of growth conditions on fibril formation, morphology, and molecular structure has not been achieved, and the full variety of fibrillar structures and morphologies that could be formed from a single peptide sequence is largely unexplored.

In this article, we investigate polymorphism in amyloid fibrils formed by residues 10–40 of the full-length Alzheimer's β-amyloid peptide (Aβ10–40). Aβ10–40 contains all the structure-forming peptide segments of the full-length sequence, and lacks only the N-terminal segment previously determined to be unstructured in Aβ1–40 fibrillar assemblies (6,8,9,11,16,17,32). Peptide fragments of Aβ1–40 with N-terminal truncations have been shown to form amyloid fibrils (33). Our investigations of Aβ10–40 fibrils were motivated originally by the hypothesis that deletion of the unstructured N-terminal segment might lead to a lower propensity for polymorphism and a higher overall level of structural order (and, hence, sharper lines in solid-state NMR spectra). We present EM, AFM, and solid-state NMR data for Aβ10–40 fibril samples grown from unseeded peptide solutions, with variations in the pH and degree of agitation of the solutions. These data show that Aβ10–40 fibrils exhibit polymorphism similar to that previously reported for Aβ1–40 fibrils. Thus, polymorphism is not driven by the presence of the disordered N-terminal segment. We also present EM, AFM, and solid-state NMR data for fibrils grown from an Aβ10–40 solution containing sonicated fragments of Aβ1–40 fibrils (i.e., a cross-seeding experiment). These data show that the morphology and molecular structure of the Aβ1–40 seeds are transferred to the Aβ10–40 fibrils, reinforcing existing evidence that the N-terminal segment does not play a role in the fibril structure.

In addition, we describe the effects of hydration on the atomic structures of Aβ10–40 fibrils, as revealed by two-dimensional (2D) solid-state 13C NMR spectra. At all 13C-labeled sites, lyophilized fibrils exhibited chemical shifts in good agreement (within ∼0.25 ppm) to those of hydrated fibrils, with marginal (≤0.3 ppm) narrowing of most NMR lines. We therefore conclude that removal of water does not change basic fibril structures. This result shows that previous suggestions that amyloid fibrils may be tubular structures filled with water (34,35) do not apply to Aβ10–40 fibrils and may not apply to fibrils formed by other peptides with similar sequences.

METHODS

Peptide preparation

Aβ10–40 (sequence YEVHHQKLVFFAEDVGSNKGAIIGLMVGGVV) was synthesized by fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chemistry with H-benzotriazol-1-yl-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate activation, using an Applied Biosystems automated peptide synthesizer (Foster City, CA) and procedures similar to those described previously for Aβ1–40 (8,9). Uniformly 13C- and 15N-labeled residues were placed at F19, V24, G25, A30, I31, and L34. These residues were chosen because of the sensitivity of their 13C NMR chemical shifts to morphological variations in earlier studies of Aβ1–40 fibrils (9). The peptide was purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography at 55°C, using a Vydac C18 column (Hesperia, CA) and a water/acetonitrile gradient with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. The purity of the final product was estimated at >95%, using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Amyloid fibrils were formed from aqueous solution at the concentrations and pH listed in Table 1. For the solutions at pH 7.5, the pH was set by a 10-mM NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4 buffer. The pH 2.76 solution was made acidic by dropwise addition of dilute acetic acid. All solutions also contained 0.01% NaN3.

TABLE 1.

Aβ10–40 fibril growth conditions and morphological properties assessed from negative stain transmission EM measurements

| Sample | Aβ10–40 concentration during growth (M) | pH during growth | Growth conditions | Apparent subunit width (nm) | Observable subunits per fibril | Fibril twist period (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 200 μM | 7.5 | Continuously sonicated | Unclear | Unclear | ∼40 |

| 2 | 75 μM | 7.5 | Quiescent | 5–6 | 2–4 | 50–100 |

| 3 | 50 μM | 7.5 | Agitated | 5–6 | 2–7 | – |

| 4 | 200 μM | 2.76 | Agitated | 5 | 2–10 | – |

| 5 | 50 μM | 7.5 | Seeded with Aβ1–40 fibril fragments | 5–6 | 2–5 | – |

Fibril formation

All samples were grown at room temperature from solutions of Aβ10–40, dissolved in 50 mL polypropylene tubes (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) by inverting the tubes and vortexing. Complete elimination of visible undissolved peptide also required several minutes of sonication in a bath sonicator (ultrasonic cleaner, Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL) Protein aggregation was monitored by eye (solution cloudiness) and by AFM (see below).

Fibril formation was allowed to occur under the conditions listed in Table 1. Five Aβ10–40 fibril samples were examined by EM and solid-state NMR. A fibril sample was deemed ready for NMR analysis when AFM and EM images showed predominantly long (>1 μm) fibrils with few (<∼5% of visible material) small (5–10 nm) spherical aggregates. Samples 1–4 were grown without seeding. The “continuously sonicated” sample (sample 1) was kept in the bath sonicator after peptide dissolution was complete; continued sonication induced a return of cloudiness due to fibril formation within ∼30 min. The “quiescent” sample (sample 2) was distributed into dialysis tubes after dissolution (1 kDa cutoff, Spectrum Laboratories, Madison, WI), and placed into a bath of pH 7.5 buffer (10 mM phosphate, 0.01% NaN3). This sample was kept in dialysis tubes for 3 months before EM and NMR analysis. The “agitated” samples (samples 3 and 4) were placed horizontally on an orbital shaker platform (VWR, Chester, PA) in their polypropylene tubes immediately after peptide dissolution, and subjected to gyration in the horizontal plane at ∼1 Hz with a radius of travel of ∼4 cm. Agitated samples were observed via AFM to be heavily fibrillar within a few days.

Fibrils in sample 5 were created by addition of an Aβ1–40 seed solution (5% by number of peptide molecules) into a solution of dissolved Aβ10–40 peptide. The Aβ1–40 fibrils were fragmented into seeds ∼200 nm in length by vigorously sonicating an initially cloudy fibril solution until it was clear (∼10 min). The parent Aβ1–40 fibrils were originally grown under “agitated” conditions; Aβ1–40 fibrils from the same original solution were the subject of previous investigations (9). Upon mixing the seed solution into the Aβ10–40 peptide solution (with both solutions initially transparent), the mixture rapidly became cloudy (∼1 min), indicating that the seeds induced Aβ10–40 fibril formation; this assertion is further supported by AFM, EM, and NMR data discussed below.

Even at lower peptide concentrations than employed previously for Aβ1–40 fibril preparations (see Table 1) (8,9), we found it difficult to dissolve the Aβ10–40 peptide without the appearance of detectable (via AFM and EM) fibrillar aggregates in solution immediately after dissolution. Based on the density of fibrils in AFM and EM images, we estimate that fibrils that were present immediately after dissolution account for <0.1% of the Aβ10–40 molecules in solution. Despite this difficulty, Aβ10–40 fibrils formed unintentionally during or before dissolution did not necessarily dominate subsequent fibril growth. For example, AFM images discussed below show that the addition of Aβ1–40 fibril seeds dramatically increased the number of fibrillar Aβ10–40 aggregates detected shortly afterward, indicating that most Aβ10–40 fibrils grew from the Aβ1–40 seeds rather than from preexisting Aβ10–40 fibrils. Furthermore, the effects of solution conditions on EM and NMR data from unseeded fibrils, as discussed below, indicate that initial distribution of peptide aggregates is not the sole determinant of Aβ10–40 fibril morphology and structure.

Electron microscopy

EM images were recorded at 26,000× magnification with a Philips/FEI transmission electron microscope (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) with a Gatan imaging filter (Pleasanton, CA) and a CCD camera. To prepare EM samples, small aliquots (∼5 μl) of Aβ10–40 solutions were diluted 10-fold with deionized water before being deposited onto freshly glow-discharged carbon films. The carbon films were supported by lacy Formvar/carbon films on 200-mesh copper grids. Drops of diluted fibril solution, 5 μL in volume, were allowed to sit for 2 min on the carbon surfaces, and then excess fluid was blotted away. The carbon surfaces were then rinsed by applying 5-μL drops of deionized water for 1 min to remove any nonfibrillar material such as buffer. Finally, the samples were negatively stained by applying 5 μL of 1% uranyl acetate for 1 min.

Most of the Aβ10–40 fibrils deposited as dense clumps on the carbon films, making it difficult to evaluate their morphologies using EM. We therefore also obtained EM images of aliquots from fibril solutions that were sonicated for a series of durations near 1 min to break up clumps of fibrils. Morphology distributions within each sample were evaluated by analyzing EM images of fibril fragments from these sonicated aliquots (see below).

Atomic force microscopy

AFM measurements were performed in air on freshly cleaved mica surfaces, using a Veeco Multimode microscope operating in tapping mode with Veeco NanoProbe tips (10-nm nominal tip radius of curvature, Veeco, Woodbury, NY). To promote adhesion of fibrils to the negatively charged mica surfaces, the pH of small aliquots of Aβ10–40 fibril solutions was lowered to 2.8 by 10-fold dilution with a dilute acetic acid solution. Acidified solutions were applied to the mica surfaces in 50-μl drops, allowed to adsorb for 2 min, then allowed to dry in air after removal of excess solution.

Solid-state NMR

For solid-state NMR experiments, fibril solutions were concentrated via ultracentrifugation for 35 min at 175,000 × g acceleration and subsequent removal of supernatant. In some cases, pelleted fibrils were resuspended in deionized water and then lyophilized. Samples were packed into 3.2 mm Varian magic-angle spinning (MAS) rotors (Varian, San Carlos, CA). For measurements on fully hydrated fibrils, wet ultracentrifuge pellets were sealed into MAS rotors using Krazy glue (gel formula) around the rotor caps. Sample mass was measured before and after NMR experiments to ensure that water had not escaped. Typical NMR rotors contained 3-6 mg of fibrillar material. Lyophilization of fibril samples allowed more material to be placed into the rotor, resulting in higher signal-to-noise ratios in the solid-state NMR spectra.

Solid state NMR spectra were recorded in a 14.1 T magnetic field (1H frequency 599.2 MHz, 13C frequency 150.7 MHz). Samples were characterized by two 2D solid-state 13C NMR techniques. Both techniques employ 1H-13C cross-polarization for signal enhancement and 110 KHz 1H decoupling with two-pulse phase modulation (36) during the evolution (t1) and signal-detection (t2) periods. The techniques differ in the method of 13C-13C dipolar recoupling during the exchange period between t1 and t2, and thus in the maximum length scales of detected interatomic chemical shift correlations (crosspeaks). The first recoupling method, finite-pulse radiofrequency-driven recoupling (fpRFDR), yields 2D NMR spectra with strong crosspeaks between chemical shifts of directly-bonded 13C atoms (37). Weaker two-bond crosspeaks are also observable. The fpRFDR pulse sequence was implemented with MAS at 20.0 kHz, an exchange period of 3.2 ms (64 rotor periods), and a π pulse width of 15.0 μs. Each 2D fpRFDR spectrum was the result of 24–36 h of signal averaging. Chemical shift assignments were obtained by tracing the crosspeak connectivity pathways in 2D fpRFDR spectra.

To obtain interatomic correlations that extend to longer length scales, additional 2D solid-state 13C NMR spectra were obtained using radiofrequency-assisted diffusion (RAD, also known as dipolar assisted rotational resonance) (38,39). With a 500-ms exchange period, 2D RAD experiments yielded longer-range correlations, such as those between 13C atoms on proximate side chains. Of particular interest to the present analysis are correlations between the spectrally isolated (between 140 and 120 ppm) aromatic 13C atoms on F19 and aliphatic 13C atoms on other labeled residues. The MAS speed was set to 18.3 KHz (121.5 ppm) to place the aromatic and methyl 13C signals near rotational resonance while avoiding spectral overlap between aromatic spinning sidebands and methyl peaks. Each 2D RAD spectrum was the result of 24–36 h of signal averaging.

Precise 13C chemical shift values and 13C MAS NMR linewidths were determined from 2D fpRFDR spectra by fitting of Gaussian functions to crosspeaks using nonlinear least-squares regression in Mathematica. Asymmetric crosspeaks from some signals were assumed to be representative of multiple structurally distinct sites for a single residue, and were fit to sums of multiple Gaussian functions. Chemical shifts extracted from these fits are reported relative to tetramethylsilane, calibrated with an external adamantane reference.

RESULTS

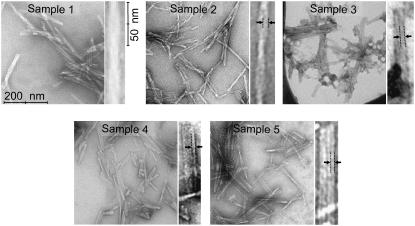

Aβ10–40 forms fibrils with morphologies that depend on growth conditions

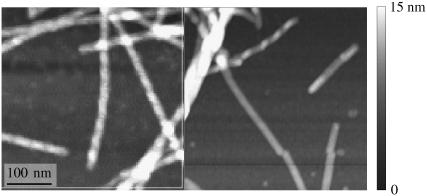

As shown in Fig. 1, all fibrils appear to be composed of multiple strands, associated in parallel or twisted around one another. We call these strands subunits, but comment that transmission EM images lack the resolution to resolve β-sheets within a fibril cross section. Subunits observed in transmission EM images therefore do not necessarily correspond to protofilaments, which were defined previously as minimal fibril structural units that could exist in isolation (9). As a basis for comparison, we define morphology based on the set of parameters listed in Table 1, which describe EM-derived apparent subunit dimensions and geometry of subunit association. Observed periodic modulation in the total widths of some fibrils is interpreted as twist due to the intertwining of subunits (9,25,26); we also measured consistent modulations in fibril height and width via AFM, as shown in Fig. 2. Subunits within untwisted fibrils tended to be found in larger groups, resulting in a ribbonlike fibrillar appearance. Previous scanning transmission EM measurements have shown that twisted (“quiescent”) Aβ1–40 fibrils have protofilaments with three peptide molecules per cross section, whereas untwisted (“agitated”) Aβ1–40 fibrils have protofilaments with two peptide molecules per cross section (9).

FIGURE 1.

Transmission EM images of fibril samples, sonicated before deposition onto carbon films. For each sample, a single fibril of the most common morphology is shown at fourfold magnification. Features within magnified fibrils that are interpreted as fibril subunits are marked with dashed lines and arrows.

FIGURE 2.

AFM images of samples 1 (left) and 4 (right), which show fibril morphologies in agreement with EM measurements. AFM images show that sample 1 contains fibrils with a twist period (modulation in height between 6 and 8 nm) of roughly 40 nm. Sample 4 contains a majority of fibrils with heights between 5 and 7 nm and no apparent twist, and a minority population of twisted fibrils.

Each sample exhibited a dominant fibril morphology (a single morphology possessed by the majority of fibrils in a sample), which varied between samples. Due to the tendency of Aβ10–40 fibrils to be found in dense clumps, the dominant morphology was best assessed when clumps were dispersed by sonication for 20–60 s (several minutes for sample 3) before deposition onto carbon surfaces. Without sonication, fibril morphology was clearly visible by EM only in regions outside fibril clumps; these regions were not necessarily representative of the dominant morphologies in the sample. Sonication decreased the apparent morphological heterogeneity in EM images, suggesting a tendency for fibrils with minority morphologies to be excluded from fibril clumps. Fig. 1 shows a transmission EM image of a sonicated aliquot of each sample. Even after sonication, sample 2 exhibited the most evidence of morphological heterogeneity, and contained significant numbers of fibrils with minority morphologies characterized by variable twist periods. For unknown reasons, sample 3 did not show fibrils in EM images without several minutes of sonication. Instead, for unsonicated preparations we detected several deposits on the carbon surface with no discernable structure. As the 2D fpRFDR NMR spectrum (chemical shifts, NMR lineshape sharpness indicating structural order) of sample 3 is consistent with amyloid fibrils, these deposits were most likely strongly-associated fibrils that were only detectable after sonication. For all the samples, sonication disrupted fibril clumps and broke fibrils into fragments between 50 and 300 nm in length. Table 1 summarizes the dominant morphologies in EM images of sonicated aliquots of fibril growth solutions.

Aβ1–40 fibrils can seed the growth of Aβ10–40 fibrils, with propagation of fibril morphology

Sample 5 was grown from a freshly dissolved Aβ10–40 solution to which sonicated fragments of Aβ1–40 fibrils were added. The Aβ1–40 fibrils had been grown with agitation as previously described (9). Addition of Aβ1–40 fibril fragments to dissolved Aβ10–40 (both solutions initially transparent) induced a rapid fibril growth as judged by the increased turbidity of the mixture. Fig. 3 shows AFM images of aliquots of the Aβ10–40 solution extracted immediately before and after addition of the Aβ1–40 fibril fragments; both of these aliquots were allowed to sit for 15 min before AFM measurement, allowing some time for fibril seeds to propagate. The AFM data indicate that addition of Aβ1–40 fibril fragments produced a rapid increase in the concentration of aggregated Aβ10–40. We subsequently observed via EM that these aggregates were fibrils whose predominant fibril morphology matches that of agitated Aβ1–40 fibrils (see Fig. 1 and Table 1) (9). Thus, we find that Aβ1–40 fibril fragments seeded the growth of Aβ10–40 fibrils, and that the morphology of the Aβ1–40 fibril seeds propagated to the resulting Aβ10–40 fibrils.

FIGURE 3.

AFM images of the sample 5 growth solution, sampled immediately before (left) and after (right) seeding with Aβ1–40 fibril fragments. Both solutions were allowed to sit for roughly 15 min before being applied to mica surfaces for AFM measurement. The image on the left indicates the presence of filamentous aggregates in the initial peptide solution, but the larger surface coverage on the right shows that the addition of seeds greatly accelerated peptide aggregation.

Solid-state NMR spectra indicate molecular-level structural variations in Aβ10–40 fibrils

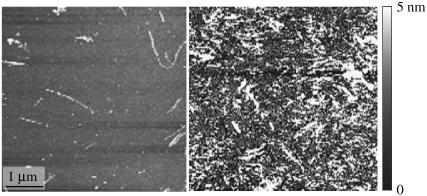

Comparison of 2D fpRFDR NMR spectra from different samples is a means of assessing secondary structures and degrees of structural similarity at the molecular level. As is well known (40), 13C chemical shifts are sensitive to variations in local molecular conformation and structural environment. In particular, we assume β-strand secondary structure to be indicated by a simultaneous shift for the carbonyl and α- and β-carbons of at least 0.5 ppm, negative for the carbonyl and Cα resonances and positive for the Cβ resonance, relative to the same amino acid within a random-coil peptide in aqueous solution (8,9,40). In addition, 13C MAS NMR linewidths are sensitive to local structural disorder in rigid solids, with greater disorder producing greater inhomogeneous broadening. Rapid molecular motions also affect 13C MAS NMR linewidths, reducing inhomogeneous broadening through motional averaging.

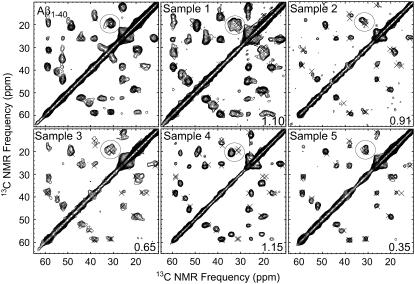

Fig. 4 shows the full 2D fpRFDR spectrum of sample 5, illustrating the ease of chemical shift assignments and the signal-to-noise ratio of 2D fpRFDR spectra of our Aβ10–40 samples. Fig. 5 shows aliphatic regions of the 2D fpRFDR spectra of all the samples, including the Aβ1–40 fibrils used to seed sample 5. Variations of crosspeak positions in these spectra are apparent relative to the “×” marks, which indicate the crosspeak positions for the Aβ1–40 fibrils. Crosspeak positions were numerically evaluated via nonlinear least-squares fitting to Gaussian lineshapes. Some peaks (such as the circled V24 Cβ-Cγ crosspeak) exhibit compound lineshapes that required fitting to the sum of multiple Gaussian functions, indicated by multiple “×” marks in close proximity. Tables 2 and 3 summarize chemical shifts and linewidths for all 13C-labeled sites in all samples.

FIGURE 4.

Illustration of 13C NMR chemical shift assignment strategy, using the 2D fpRFDR spectrum of sample 5. Strong crosspeaks (symmetric about the diagonal) are due to exchange of nuclear spin polarization between directly bonded 13C atoms, allowing chemical shift assignment through comparison with known bonding patterns in the labeled residues. Additional peaks, due to MAS side bands of the carbonyl and aromatic resonances, are marked with an asterisk. Below the 2D fpRFDR spectrum are horizontal slices taken at the specified frequencies, shown to demonstrate the signal-to-noise ratios. The 2D fpRFDR spectra were acquired at a 150.7 MHz 13C NMR frequency, with a 20 kHz MAS frequency and a 3.2-ms mixing period.

FIGURE 5.

Aliphatic regions of 2D fpRFDR spectra for each Aβ10–40 fibril sample (samples 2, 4, and 5 were hydrated, the others lyopholized). Also shown is the spectrum of Aβ1–40 fibrils similar to those used to seed sample 5, which included an additional 13C/15N uniformly labeled residue at M35, and hence extra NMR signals at 52.6, 35.1, and 29.9 ppm. The “×” marks indicate crosspeak positions for the Aβ1–40 spectrum, and are included as a reference in all spectra. The number in the lower right of each spectrum is the root-mean-squared deviation of peak positions (ppm) from those of corresponding Aβ1–40 fibril signals, calculated for the aliphatic region of the 2D fpRFDR spectrum. The circled V24 Cβ-Cγ crosspeaks exhibit significant variability between samples, and are also a good point of comparison. Aside from differences in signal averaging time, all spectra were acquired under identical experimental conditions.

TABLE 2.

Chemical shifts (ppm relative to tetramethylsilane) for all 13C-labeled sites in all samples

| Residue | Sample | CO | Cα | Cβ | Cγ | Cδ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F19 | Aβ1–40 | 169.7 | 54.8 | 40.7 | (136.5, 134.9) | 128.7 |

| 1 | 170.6 | 56.0* | 42.0 | 136.0 | 129.1 | |

| 2 (h) | (169.8, 170.8) | (54.0, 54.7) | 42.1 | (133.9, 135.3) | 129.5 | |

| 3 | 169.9 | 54.5 | (41.7, 40.1) | 136.1 | 129.3 | |

| 4 (h) | 170.5 | 54.5 | 40.6 | 137.0 | 128.8 | |

| 5 (h) | 170.1 | 55.0 | 41.5 | (136.1, 134.5) | 129.5 | |

| Random coil | 174.1 | 56.0 | 37.9 | 137.2 | 130.2, 129.8, 128.2 | |

| V24 | Aβ1–40 | 173.9 | 58.5 | (31.0*, 30.9*, 31.5*) | (18.7, 20.3, 19.4) | – |

| 1 | 174.1 | (58.9, 59.3) | (33.1, 30.8*) | 19.2, 20.3 | – | |

| 2 (h) | 174.8* | (57.4, 58.8) | (32.5, 31.1*) | 17.9, 18.8 | – | |

| 3 | 173.2 | 58.5 | (30.5*, 32.7) | 18.8, 19.1 | – | |

| 4 (h) | 173.9 | 56.6 | 34 | 20.7 | – | |

| 5 (h) | 174.0 | 58.5 | (30.9*, 31.9) | (17.9, 20.0, 19.4) | – | |

| Random coil | 174.6 | 60.5 | 31.2 | 18.6, 19.4 | – | |

| G25 | Aβ1–40 | 170.6 | 46.7* | – | – | – |

| 1 | 171.9 | 45.2* | – | – | – | |

| 2 (h) | 171.1 | 47.5* | – | – | – | |

| 3 | 169.8 | 46.2* | – | – | – | |

| 4 (h) | 171.6 | 47.3* | – | – | – | |

| 5 | 171.6 | 47.3* | – | – | – | |

| Random coil | 173.2 | 43.4 | – | – | – | |

| A30 | Aβ1–40 | 172.7 | (48.2, 49.8) | (21.1, 19.1, 20.3) | – | – |

| 1 | 174.0 | 49.0 | 20.1 | – | – | |

| 2 (h) | (172.8, 174.0) | (49.0, 48.4) | (19.8, 20.9) | – | – | |

| 3 | 172.7 | 48.6 | (19.1, 20.9) | – | – | |

| 4 (h) | 172.2 | 48.6 | 19.5 | – | – | |

| 5 (h) | 172.2 | 48.6 | 19.5 | – | – | |

| Random coil | 176.1 | 50.8 | 17.4 | – | – | |

| I31 | Aβ1–40 | 172.2 | 59.0* | (38.0, 38.4) | (26.3, 25.7) (17.4, 15.2) | 11.5 |

| 1 | 172.6 | 59.4* | 38.8 | 26.3, 16.4 | 12.5 | |

| 2 (h) | (172.5, 173.0) | (59.6*, 59.0*) | (37.0*, 38.2) | 25.6 15.9 | (10.4, 12.2) | |

| 3 | 172.0 | 58.8 | (38.0, 38.5) | 25.5 15.2 | (11.6, 14.1) | |

| 4 (h) | 171.6 | 58.6 | 38.4 | 25.6 16.5 | 12.9 | |

| 5 (h) | 172.5 | 58.9 | 38.3 | (25.8, 26.6) (17.7, 15.9) | (11.9, 14.1) | |

| Random coil | 174.7 | 59.4 | 37.1 | 25.5, 15.7 | 11.2 | |

| L34 | Aβ1–40 | 171.5 | 52.2 | 44.2 | 25.9 | 25.8, 24.6 |

| 1 | 171.8 | 52.8 | 45.0 | 26.9 | 26.2, 25.0 | |

| 2 (h) | 170.8 | 52.2 | 43.8 | 26.2 | 22.4, 23.8 | |

| 3 | 171.4 | 52.0 | 44.0 | 25.8 | 23.1, 24.1 | |

| 4 (h) | 171.5 | 52.7 | 45.8 | 26.7 | 25.1, 22.3 | |

| 5 (h) | 171.7 | 52.1 | 43.9 | 26.3 | 26.2, 23.8 | |

| Random coil | 175.9 | 53.4 | 40.7 | 25.2 | 21.6, 23.2 |

Values in parentheses indicate more NMR lines than corresponding 13C-labeled sites, suggesting the presence of multiple structures within a sample, and are reported in order of decreasing peak intensity. The parenthetical “h” indicates that values were obtained from 2D fpRFDR spectra of hydrated samples. Chemical shifts marked with asterisks are not consistent with a β-strand conformation (β-strand conformations are indicated by deviations of at least 0.5 ppm from the random-coil shifts, negative for CO and Cα and positive for Cβ). Random coil values are taken from Wishart et al. (45), adjusted to the tetramethylsilane reference by subtraction of 1.7 ppm.

TABLE 3.

Linewidths (full width at half maximum, in ppm) for all 13C-labeled sites in all samples

| Residue | Sample | CO | Cα | Cβ | Cγ | Cδ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F19 | 1 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 1.4 |

| 2 (h) | (1.1, 2.2) | (0.9, 1.05) | (1.2, 2.2) | (1.6, 1.6) | 1.9 | |

| 3 | 2.2 | 2.1 | (1.9, 1.4) | 1.7 | 2.5 | |

| 4 (h) | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 3.0 | |

| 5 (h) | 1.3 | 2.2 | 2.9 | (1.3, 1.6) | 1.3 | |

| Aβ1–40 | 3.3 | 2.2 | 2.6 | (1.6, 2.6) | 2.1 | |

| V24 | 1 | 3.0 | (1.8, 2.2) | (2.4, 2.2) | (3.2, 4.1) | – |

| 2 (h) | 1.4 | (1.1, 1.0) | (1.7, 2.5) | (1.5, 1.8) | – | |

| 3 | 3.5 | 1.6 | (2.6, 1.9) | 3.8, 3.1 | – | |

| 4 (h) | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 2.0 | – | |

| 5 (h) | 1.5 | 1.9 | (1.8, 1.5) | (1.1, 1.3, 3.4) | – | |

| Aβ1–40 | 2.2 | 1.4 | (1.3, 1.2, 4.4) | (1.3, 1.2, 3.3) | – | |

| G25 | 1 | 3.0 | 5.6 | – | – | – |

| 2 (h) | 1.7 | 1.3 | – | – | – | |

| 3 | 2.1 | 2.0 | – | – | – | |

| 4 (h) | 2.0 | 1.2 | – | – | – | |

| 5 (h) | 1.9 | 1.6 | – | – | – | |

| Aβ1–40 | 1.7 | 1.6 | – | – | – | |

| A30 | 1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2.7 | – | – |

| 2 (h) | (1.2, 1.5) | (1.5, 1.0) | (2.9, 1.6) | – | – | |

| 3 | 2.6 | 2.3 | (2.8, 1.7) | – | – | |

| 4 (h) | 1.6 | 1.1 | 2.0 | – | – | |

| 5 (h) | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.6 | – | – | |

| Aβ1–40 | 2.0 | (1.6, 1.6) | (1.0, 7.6, 3.2) | – | – | |

| I31 | 1 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.5, 1.9 | 2.5 |

| 2 (h) | (1.4, 2.8) | (0.8, 1.4) | (1.0, 1.2) | 1.5, 1.2 | (1.2, 2.3) | |

| 3 | 1.4 | 2.3 | (1.4, 2.9) | 2.0 3.5 | (2.1, 1.7) | |

| 4 (h) | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.1, 1.4 | 1.1 | |

| 5 (h) | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.1 | (1.9, 1.4), (1.0, 2.3) | (1.5, 2.0) | |

| Aβ1–40 | 1.7 | 1.7 | (1.3, 2.4) | (1.2, 2.3), (1.4, 3.3) | (1.1, 2.6) | |

| L34 | 1 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 5.1, 1.2 |

| 2 (h) | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.7, 2.8 | |

| 3 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.7, 1.0 | |

| 4 (h) | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1, 1.1 | |

| 5 (h) | 2.1 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.8, 2.6 | |

| Aβ1–40 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 1.5, 2.5 |

The parenthetical “h” indicates that values were obtained from 2D fpRFDR spectra of hydrated samples. Values enclosed in parentheses indicate more NMR lines than corresponding 13C-labeled sites, suggesting the presence of multiple structures within a sample, and are reported in order of decreasing peak intensity.

Fig. 5 also reports for each sample the root-mean-squared deviation of Aβ10–40 fibril crosspeak positions from the corresponding positions of Aβ1–40 fibril crosspeaks. The best agreement with the Aβ1–40 spectrum was found in the spectrum of sample 5. This spectroscopic similarity suggests that the molecular structure of the Aβ1–40 fibrils propagated through seeding to the Aβ10–40 fibrils, and is consistent with the propagation of morphology observed via EM. Chemical shifts similar to those of sample 5 and the Aβ1–40 sample were also found in the spectrum of sample 3, which was grown under agitated conditions similar to those used originally for the growth of Aβ1–40 fibrils (9). Although samples 3 and 5 and Aβ1–40 exhibited similar 2D fpRFDR spectra, samples 1, 2, and 4 each exhibited a unique set of chemical shifts.

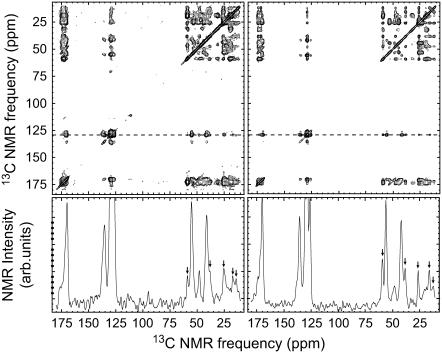

Two-dimensional RAD spectra, such as those in Fig. 6, reveal information about tertiary structure within the amyloid fibrils. In the structural model for Aβ1–40 amyloid protofilaments developed in 2002 by Petkova et al. (8), each peptide molecule contains two β-strand segments (residues 9–23 and 30–40), separated by a bend or loop segment (residues 24–29) that allows side chains in the two β-strands to make contact with one another. In this model, side chains of F19 residues are within 10 Å of side chains of I31. When this model was developed, no direct evidence was available for side-chain contacts in the interior of the protofilament, other than measurements of 15N-13C nuclear magnetic dipole-dipole couplings that indicated the presence of a salt bridge between oppositely charged side chains of D23 and K28 (8,9). For all Aβ10–40 fibril samples, 2D RAD spectra contain crosspeaks between the spectrally isolated aromatic 13C signals from the F19 side chain and methyl sites on other labeled residues. This observation, and the measured 13C chemical shifts of carbonyl and α- and β-carbon sites, which mostly indicate β-strand conformations, are generally consistent with the pattern for peptide secondary structure proposed previously (8).

FIGURE 6.

2D RAD spectra from samples 1 (right) and 5 (left). Below each spectrum is a horizontal cross section at the frequency of maximal aromatic intensity. The peaks in these cross sections marked by arrows indicate sample-dependent proximities between side chains of F19 and other isotopically labeled residues. Spectra were acquired at a 150.7 MHz 13C NMR frequency, with an 18.3-kHz MAS frequency and a 500-ms exchange period.

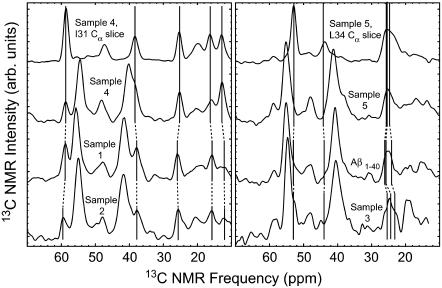

Crosspeaks between F19 aromatic 13C signals and 13C signals from other labeled side chains are described in more detail in the one-dimensional slices of 2D RAD spectra shown in Fig. 7, which are expansions of the aliphatic regions (10–70 ppm). These data indicate sample-dependent variations in specific side-chain proximities to F19. In Fig. 7, the one-dimensional spectra of aliphatic-to-aromatic correlations are divided into two groups, depending on whether the F19 side chain was close to I31 or L34. The most notable difference between spectra in Fig. 7 is in the breadth of the peak near 25 ppm. The spectra on the left (samples 1, 2, and 4) show a narrow peak centered just below 26 ppm, whereas the spectra on the right (samples 3, 5, and Aβ1–40) show a broad peak between 22 and 26 ppm. The data on the left indicate proximity between F19 atomatic carbons and the I31 Cγ, with additional correlations to I31 α, β, and δ carbons near 59, 38, 14, and 12 ppm, respectively. For the spectra on the right side of Fig. 7 (Aβ1–40 fibrils and Aβ10–40 samples 3 and 5), the broad peak between 22 and 26 ppm is due to overlapping contacts to L34 γ and δ carbons, indicating proximity between F19 and L34 side chains. In these samples, correlations between F19 aromatic carbons and the α and β carbons on L34 are not visible outside the noise. The lack of F19 contacts to α and β carbons of L34 is consistent with the low intensity of the contact to L34 Cγ and Cδ, given that the latter peak is due to contributions from three L34 carbon atoms. The distinct visibility of every F19–I31 contact for the data on the left side of Fig. 7 suggests that F19 may be closer to I31 in samples 1, 2, and 4 than to L34 in samples 3, 5, and Aβ1–40.

FIGURE 7.

One-dimensional (sum of horizontal and vertical) slices through 2D RAD spectra. The top spectra on the left and right are slices through the I31 and L34 Cα peak positions, respectively. All other spectra are slices through the frequencies of maximal aromatic intensity (see Fig. 6), for samples 1, 2, and 4 on the left,and Aβ1–40 and samples 3 and 5 on the right. Spectra on the left show F19–I31 correlations, whereas those on the right show F19–L34 correlations. The vertical lines indicate peak positions for I31 or L34 13C-labeled sites, which vary between samples. Unmarked peaks near 48 ppm, 42 ppm, and 20 ppm are assigned to carbonyl MAS sidebands, F19 β-carbons, and A30 methyl carbons, respectively. Aside from differences in signal averaging time, all spectra were acquired under identical conditions.

Aromatic contacts from sample 5 (Fig. 7, right) contain weak I31 signals. Since these I31 peaks are shifted from the strongest I31 signals in the 2D fpRFDR specta, they are likely to represent minority fibril structures. Sample 2 shows a slight broadening of the aromatic contact near 26 ppm that could indicate a minority structure with F19–L34 proximity.

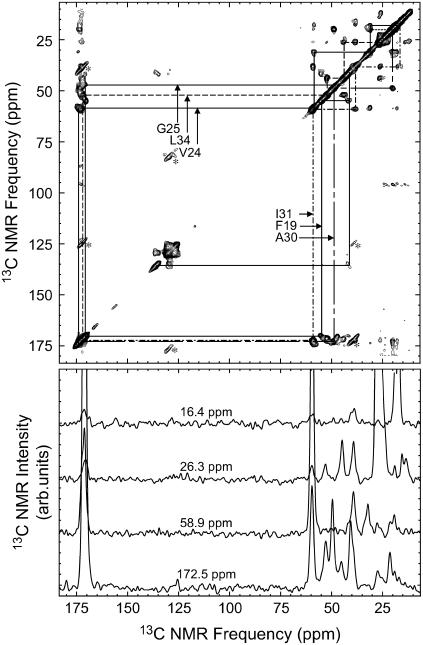

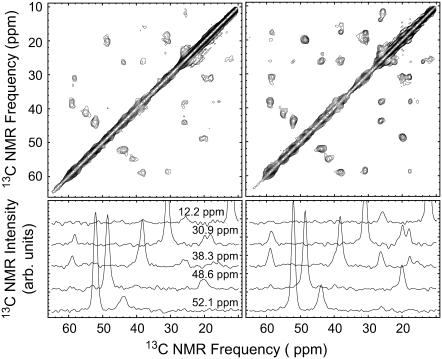

Hydration does not affect Aβ10–40 fibril structure

The spectra from samples 2, 4, and 5 in Fig. 5 were obtained from hydrated fibrils, i.e., ultracentrifuge pellets placed directly into MAS NMR rotors. The remaining spectra are from lyophilized fibril samples. Fig. 8 compares the aliphatic regions of 2D fpRFDR spectra from sample 5, in both lyophilized and hydrated states. We observed no effect (estimated error ∼0.25 ppm) of lyophilization on the 13C NMR chemical shifts, indicating that lyophilization induces no detectable structural changes in Aβ10–40 fibrils. Hahn echo measurements of 13C spin-spin relaxation showed little effect of hydration on carbonyl and Cα relaxation times (hydrated fibrils: carbonyl T2 = 9.1 ± 0.2 ms, Cα T2 = 3.4 ± 0.4 ms; lyophilized fibrils: carbonyl T2 = 9.7 ± 0.5 ms, Cα T2 = 3.4 ± 0.4 ms), suggesting that hydration has little effect on backbone mobility. Lyophilization did result in broadening of methyl carbon 13C NMR lines by 1–2 ppm, and a marginal broadening of ∼0.3 ppm of other lines. The significant narrowing of methyl 13C NMR lines results in the appearance of additional two-bond crosspeaks in the 2D fpRFDR spectrum of hydrated fibrils in Fig. 8. Despite the narrower NMR lines from hydrated samples, NMR experiments on hydrated fibrils required more signal averaging due to the presence of less material in the NMR rotor. We also compared NMR measurements of hydrated and lyophilized fibrils from samples 2 and 4, and obtained similar results (not shown).

FIGURE 8.

Aliphatic regions of 2D fpRFDR spectra for sample 5 in lyophilized form (left) and in fully hydrated form (ultracentrifuge pellet, right). Below are horizontal slices at the specified NMR frequencies.

DISCUSSION

Analysis of structural variations

The NMR chemical shifts (Table 2) and 2D RAD contacts (Fig. 7) from all Aβ10–40 fibril samples are consistent with the structural motif (two β-strand regions brought into proximity by a “bend” or “loop” region) proposed in the previous structural model for Aβ1–40 amyloid protofilaments (8), but the data also indicate significant structural deviations within this motif. The chemical shifts of carbonyl and α- and β-carbons from F19, A30, I31, and L34 were found to be mostly consistent with β-strand backbone conformations (as an exception, some I31 Cα signals were less shifted from the random coil value than expected). V24 and G25 carbonyl and α- and β-carbon signals were not generally consistent with β-strand conformations, and showed larger variations in chemical shift from sample to sample; these residues may be in the non-β-strand “bend” or “loop” region predicted by the structural model. Away from the peptide backbone, the largest sample-dependent deviations in chemical shift were observed for the methyl carbons of L34 and I31 (L34 Cδ, I31 Cγ, and Cδ); these signals are likely to depend more on environment than on backbone conformation. Each spectrum in Fig. 5 is most easily distinguished from the others by the compound lineshape of the V24 Cβ-Cγ crosspeak and the positions of the I31 and L34 methyl carbons.

Long-range correlations probed through 2D RAD experiments indicate variations in side-chain contacts within the fibrillar hydrophobic core (Figs. 6 and 7). Within the folded β-strand structural motif for Aβ amyloid fibrils, F19 is part of the β-sheet formed by residues 9–23, and L34 and I31 are on opposite faces of the β-sheet formed by residues 30–40. The Aβ10−40 fibril samples exhibiting F19–I31 proximity may possess structures that are consistent with the previous structural model, which predicts that both side chains will be within the hydrophobic core (8). In contrast, proximity between F19 and L34 detected in other Aβ10–40 samples requires a reversal of the orientation of the β-sheet formed by residues 30–40 relative to that of the β-sheet formed by residues 9–23, such that L34 rather than I31 is within the hydrophobic core. Such a large variability in molecular structure between samples illustrates the nonspecific nature of the hydrophobic interactions that stabilize fibrillar assemblies. This observed variability is consistent with the findings of Shivaprasad and Wetzel, who used cysteine double mutants of Aβ1–40 to show that the ability to form amyloid fibrils was eliminated neigher by cross-linking between residues 17 and 35 nor by cross-linking between residues 17 and 34 (20).

The 2D fpRFDR and 2D RAD NMR data together indicate that some sets of samples possessed similar molecular structures, whereas other samples possessed unique molecular structures. Sample 5 showed the best spectral similarity to Aβ1–40 (from which it was seeded) in terms of 2D fpRFDR-derived peak positions and lineshapes, as well as 2D RAD aromatic contacts (F19–L34). Some spectral differences, such as sharpening of the A30 Cα-Cβ crosspeak into a symmetric peak could be explained by sharpening of NMR lines via hydration of sample 5. Sample 3 also exhibited similar chemical shifts and 2D RAD aromatic contacts to sample 5 and Aβ1–40, suggesting that seeding is not a requirement for formation of Aβ10–40 fibrils of this structure. In contrast to the samples showing F19–L34 side-chain proximity, the samples 1, 2, and 4 each showed different 2D fpRFDR spectra, and must each represent a unique molecular structure. Sample 4 is easily distinguished from the other samples through the V24 signals, which are consistent with β-strand secondary structure. This difference in the conformation of the turn region is likely due to protonation of the E22 side chain (pKa ≈ 4.4 in unstructured peptides) at low pH (see Table 1). Sample 2, which was grown under quiescent conditions, exhibited the most disorder in the 2D fpRFDR NMR spectrum, with the lowest signal-to-noise ratios and the greatest tendency to show multiple NMR signals for single labeled sites (see Tables 2 and 3).

Variations in molecular structure were accompanied by variations in fibril morphology observed by EM (Fig. 1). Previous work suggests that amyloid fibrils that exhibit similar morphologies may have similar underlying atomic structures (9). The untwisted dominant fibril morphology of sample 5 is consistent with that of the “agitated” Aβ1–40 fibrils with which growth of sample 5 was seeded (9); underlying atomic-level structural similarity was confirmed through 2D fpRFDR NMR spectra. Other samples with a similar untwisted dominant morphology were samples 3 and 4. Sample 4 exhibited NMR chemical shifts similar to those seen in sample 5, but sample 3 did not. One morphological parameter distinguishing different untwisted fibrils is the degree of lateral association of multiple subunits per fibril (see Table 1). Predominantly twisted fibrils were observed in samples 1 and 2, each of which showed a distinct set of NMR chemical shifts. Different twisted fibril morphologies can be distinguished through differences in twist period and the width of subunits. The greatest variety of chemical shifts and fibril morphologies within a single sample was observed in sample 2, suggesting that quiescent conditions promote the propagation of multiple types of fibrils.

Insights into fibril formation processes

A solution of mature amyloid fibrils is the product of three general processes influencing fibril formation. First, fibril formation requires that dissolved peptide molecules initially aggregate into critical nuclei (41). These critical nuclei must then grow into fibrils by addition of new peptide molecules. As fibril growth continues, kinetics could accelerate if propagating amyloid fibrils were to break apart and increase the number of sites available for addition of new peptide (42). The variety of fibrillar atomic structures and morphologies measured here is evidence that critical nuclei can be formed with numerous molecular structures. The specific fibril structure and morphology that eventually dominates a solution is likely to depend on the effects of solution environment on nucleus formation and propagation.

The influence of subtle environmental factors on fibrillar growth, structure, and morphology can be easily seen through the effects of solution agitation (e.g., shaking or sonication) during fibril formation. In unseeded fibril preparations, agitation accelerated growth kinetics and favored the dominance of a single fibril type. The most highly disordered sample analyzed here, sample 2, was grown under quiescent conditions. This sample exhibited a variety of fibril morphologies (variable twist periods) when probed by EM, and the greatest disorder in the NMR spectra (multiple NMR signals for each of many 13C labeled sites; see Table 2). Though fibril growth kinetics were not quantitatively monitored, periodic AFM and EM measurement of sample 2 after peptide dissolution indicated that fibrils in this solution grew slowly over months. In contrast, sample 1, which was sonicated continuously for several minutes, was found to be heavily fibrillar immediately after sonication. Samples 3 and 4, which were grown on an orbital shaker, developed mature fibrils within a few days. All agitated samples showed more structural order (via NMR) and less morphological heterogeneity (via EM) than the quiescent fibrils.

Several factors could account for the effect of solution agitation on fibril morphology. Increased possibility for interactions with the walls of the container or with the air-water interface through increased solution surface area and enhanced molecular transport could have promoted alternative pathways for fibril nucleation. In previous studies of Aβ1–40 fibrils (9), pretreatment of Aβ1–40 with hexafluoroisopropanol or sodium hydroxide did not affect the dependence of fibril morphology on agitation. Since we did not employ such methods for dissociating preformed peptide aggregates in our studies of Aβ10–40, it is possible that all observed fibrils propagated from different fibril nuclei initially present upon solution preparation. During subsequent fibril propagation, shear stresses induced by agitation provided a means of breaking apart growing fibrils; agitation could thus have preferentially accelerated growth of fibrils that fragmented more easily. A better understanding of fibril nucleation and growth would require techniques to evaluate initial distributions of fibril seed structures, and structure-sensitive measurements of growth kinetics.

Aβ10–40 fibrils are not water-filled

The absence of 13C NMR chemical shift differences between fully hydrated and lyophilized Aβ10–40 fibrils (observed from samples 2, 4, and 5) is strong evidence that bulk water does not play a significant role in β-amyloid fibril structures. It appears unlikely that these fibrils are water-filled nanotubes, as suggested by Perutz et al. (34). Removal of bulk water did not produce detectable changes in peptide backbone or side-chain conformations. The only detected effect of lyophilization was the broadening of some 13C NMR lines, particularly from side-chain methyl carbons, which we attribute to reduced motional narrowing and hence increased inhomogeneous broadening in the lyophilized state. The lack of bulk water in the Aβ10–40 fibril structure may be due to the hydrophobic nature of the majority of fibril-stabilizing interactions; the fibrils analyzed by Perutz et. al. are believed to be stabilized by glutamine polar zippers (34) and may thus be more likely to include bulk water, but Chan et al. have shown that lyophilization also does not affect NMR chemical shifts in fibrils formed by residues 10–39 of the Ure2p yeast prion protein, which has a sequence rich in asparagine and glutamine residues (43).

General implications

The data presented above extend our understanding of amyloid fibril formation by the Alzheimer's β-amyloid peptide in several ways: 1), The EM, AFM, and solid-state NMR data clearly show that the Aβ10–40 sequence is capable of forming amyloid fibrils with multiple morphologies and molecular structures, as has been shown previously for the full-length Aβ1–40 sequence. Polymorphism in Aβ1–40 fibrils is therefore not attributable to the N-terminal segment, which is the most disordered segment in the fibrils (8,32). Instead, polymorphism in Aβ1–40 and Aβ10–40 fibrils is a property of the more structurally ordered part of the sequence, most likely reflecting multiple alternatives for the packing and interactions of side chains within the core of the fibril with similar free energies. 2), Variations in contacts between the F19 side chain and aliphatic side chains in residues 30–40, revealed by the 2D RAD spectra, support the idea that polymorphism results at least in part from variations in interactions between side chains at the interfaces between β-sheets. The F19–L34 contacts observed in samples 3 and 5 are consistent with β-sheet contacts identified in the crosslinking studies of Wetzel and co-workers (20), but the F19 I31 contacts observed in samples 1, 2, and 4 indicate an alternative set of β-sheet contacts. 3), Although 13C NMR linewidths for certain Aβ10–40 fibril samples are slightly reduced relative to linewidths for Aβ1–40 fibrils, the differences are small. Thus, although one of the original motivations for the studies discussed above was to produce better-ordered fibrils with sharper solid-state NMR signals, we find that the degree of residual structural disorder in residues 10–40 is not strongly affected by the presence or absence of the disordered N-terminal segment. The main effect of deleting the N-terminal segment in our experiments is to reduce the initial solubility of Aβ10–40 relative to that of Aβ1–40. It has been shown that amyloid plaques in human Alzheimer's disease contain β-amyloid peptides with N-terminal truncations (44). Although it is not known whether N-terminal truncation occurs before or after plaque formation, the possibility exists that N-terminal truncation by proteases accelerates plaque formation in Alzheimer's disease (4). The ability of Aβ1–40 fibril fragments to act as seeds for Aβ10–40 fibril growth, with preservation of fibril morphology and molecular structure, is consistent with residues 1–9 being disordered and positioned outside the fibril core. Moreover, the seeding ability seems to indicate that residues 1–9 are disordered even at the ends of Aβ1–40 fibril fragments, where the peptide conformations and intermolecular interactions may be different from those in the interior. If residues 1–9 were part of an ordered structure at the fibril fragment ends, then binding of Aβ10–40 molecules to the ends, which is presumably a prerequisite for seeded fibril growth, might be energetically or kinetically unfavorable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Wai-Ming Yau for assistance with peptide synthesis and purification and Dr. Richard D. Leapman for assistance with electron microscopy.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

Aneta T. Petkova's present address is Dept. of Physics, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

References

- 1.Booth, D. R., M. Sunde, V. Bellotti, C. V. Robinson, W. L. Hutchinson, P. E. Fraser, P. N. Hawkins, C. M. Dobson, S. E. Radford, C. C. Blake, and A. M. Pepys. 1997. Instability, unfolding and aggregation of human lysozyme variants underlying amyloid fibrillogenesis. Nature. 385:787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiti, F., P. Webster, N. Taddei, A. Clark, M. Stefani, G. Ramponi, and C. M. Dobson. 1999. Designing conditions for in vitro formation of amyloid protofilaments and fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:3590–3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dobson, C. M. 2003. Protein folding and misfolding. Nature. 426:884–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sunde, M., and C. C. F. Blake. 1998. From the globular to the fibrous state: protein structure and structural conversion in amyloid formation. Q. Rev. Biophys. 31:1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sipe, J. D. 1992. Amyloidosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 61:947–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balbach, J. J., A. T. Petkova, N. A. Oyler, O. N. Antzutkin, D. J. Gordon, S. C. Meredith, and R. Tycko. 2002. Supramolecular structure in full-length Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibrils: evidence for a parallel β-sheet organization from solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance. Biophys. J. 83:1205–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balbach, J. J., Y. Ishii, O. N. Antzutkin, R. D. Leapman, N. W. Rizzo, F. Dyda, J. Reed, and R. Tycko. 2000. Amyloid fibril formation by Aβ16–22, a seven-residue fragment of the Alzheimer's β-amyloid peptide, and structural characterization by solid state NMR. Biochemistry. 39:13748–13759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petkova, A. T., Y. Ishii, J. J. Balbach, O. N. Antzutkin, R. D. Leapman, F. Delaglio, and R. Tycko. 2002. A structural model for Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibrils based on experimental constraints from solid state NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:16742–16747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petkova, A. T., R. D. Leapman, Z. H. Guo, W. M. Yau, M. P. Mattson, and R. Tycko. 2005. Self-propagating, molecular-level polymorphism in Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibrils. Science. 307:262–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaroniec, C. P., C. E. MacPhee, V. S. Bajaj, M. T. McMahon, C. M. Dobson, and R. G. Griffin. 2004. High-resolution molecular structure of a peptide in an amyloid fibril determined by magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:711–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antzutkin, O. N., J. J. Balbach, R. D. Leapman, N. W. Rizzo, J. Reed, and R. Tycko. 2000. Multiple quantum solid-state NMR indicates a parallel, not antiparallel, organization of β-sheets in Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:13045–13050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petkova, A. T., G. Buntkowsky, F. Dyda, R. D. Leapman, W. M. Yau, and R. Tycko. 2004. Solid state NMR reveals a pH-dependent antiparallel β-sheet registry in fibrils formed by a β-amyloid peptide. J. Mol. Biol. 335:247–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torok, M., S. Milton, R. Kayed, P. Wu, T. McIntire, C. G. Glabe, and R. Langen. 2002. Structural and dynamic features of Alzheimer's Aβ peptide in amyloid fibrils studied by site-directed spin labeling. J. Biol. Chem. 277:40810–40815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Der-Sarkissian, A., C. C. Jao, J. Chen, and R. Langen. 2003. Structural organization of α-synuclein fibrils studied by site-directed spin labeling. J. Biol. Chem. 278:37530–37535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayasinghe, S. A., and R. Langen. 2004. Identifying structural features of fibrillar islet amyloid polypeptide using site-directed spin labeling. J. Biol. Chem. 279:48420–48425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whittemore, N. A., R. Mishra, I. Kheterpal, A. D. Williams, R. Wetzel, and E. H. Serpersu. 2005. Hydrogen-deuterium (H/D) exchange mapping of Aβ1–40 amyloid fibril secondary structure using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 44:4434–4441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang, S. S. S., S. A. Tobler, T. A. Good, and E. J. Fernandez. 2003. Hydrogen exchange-mass spectrometry analysis of β-amyloid peptide structure. Biochemistry. 42:9507–9514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritter, C., M. L. Maddelein, A. B. Siemer, T. Luhrs, M. Ernst, B. H. Meier, S. J. Saupe, and R. Riek. 2005. Correlation of structural elements and infectivity of the HET-s prion. Nature. 435:844–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams, A. D., E. Portelius, I. Kheterpal, J. T. Guo, K. D. Cook, Y. Xu, and R. Wetzel. 2004. Mapping Aβ amyloid fibril secondary structure using scanning proline mutagenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 335:833–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shivaprasad, S., and R. Wetzel. 2004. An intersheet packing interaction in Aβ fibrils mapped by disulfide cross-linking. Biochemistry. 43:15310–15317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon, D. J., J. J. Balbach, R. Tycko, and S. C. Meredith. 2004. Increasing the amphiphilicity of an amyloidogenic peptide changes the β-sheet structure in the fibrils from antiparallel to parallel. Biophys. J. 86:428–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lansbury, P. T., P. R. Costa, J. M. Griffiths, E. J. Simon, M. Auger, K. J. Halverson, D. A. Kocisko, Z. S. Hendsch, T. T. Ashburn, R. G. S. Spencer, B. Tidor, and R. G. Griffin. 1995. Structural model for the β-amyloid fibril based on interstrand alignment of an antiparallel-sheet comprising a C-terminal peptide. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2:990–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burkoth, T. S., T. L. S. Benzinger, V. Urban, D. M. Morgan, D. M. Gregory, P. Thiyagarajan, R. E. Botto, S. C. Meredith, and D. G. Lynn. 2000. Structure of the β-amyloid(10–35) fibril. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122:7883–7889. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kammerer, R. A., D. Kostrewa, J. Zurdo, A. Detken, C. Garcia-Echeverria, J. D. Green, S. A. Muller, B. H. Meier, F. K. Winkler, C. M. Dobson, and M. O. Steinmetz. 2004. Exploring amyloid formation by a de novo design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:4435–4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldsbury, C. S., S. Wirtz, S. A. Muller, S. Sunderji, P. Wicki, U. Aebi, and P. Frey. 2000. Studies on the in vitro assembly of Aβ 1–40: implications for the search for Aβ fibril formation inhibitors. J. Struct. Biol. 130:217–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jimenez, J. L., E. J. Nettleton, M. Bouchard, C. V. Robinson, C. M. Dobson, and H. R. Saibil. 2002. The protofilament structure of insulin amyloid fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:9196–9201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harper, J. D., S. S. Wong, C. M. Lieber, and P. T. Lansbury. 1997. Observation of metastable Aβ amyloid protofibrils by atomic force microscopy. Chem. Biol. 4:119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bessen, R. A., and R. F. Marsh. 1992. Biochemical and physical properties of the prion protein from 2 strains of the transmissible mink encephalopathy agent. J. Virol. 66:2096–2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Telling, G. C., P. Parchi, S. J. DeArmond, P. Cortelli, P. Montagna, R. Gabizon, J. Mastrianni, E. Lugaresi, P. Gambetti, and S. B. Prusiner. 1996. Evidence for the conformation of the pathologic isoform of the prion protein enciphering and propagating prion diversity. Science. 274:2079–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Safar, J., H. Wille, V. Itrri, D. Groth, H. Serban, M. Torchia, F. E. Cohen, and S. B. Prusiner. 1998. Eight prion strains have PrPSc molecules with different conformations. Nat. Med. 4:1157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chien, P., and J. S. Weissman. 2001. Conformational diversity in a yeast prion dictates its seeding specificity. Nature. 410:223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kheterpal, I., A. Williams, C. Murphy, B. Bledsoe, and R. Wetzel. 2001. Structural features of the Aβ amyloid fibril elucidated by limited proteolysis. Biochemistry. 40:11757–11767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hilbich, C., B. Kisterswoike, J. Reed, C. L. Masters, and K. Beyreuther. 1991. Aggregation and secondary structure of synthetic amyloid βA4 peptides of Alzheimer's. J. Mol. Biol. 218:149–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perutz, M. F., J. T. Finch, J. Berriman, and A. Lesk. 2002. Amyloid fibers are water-filled nanotubes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:5591–5595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kishimoto, A., K. Hasegawa, H. Suzuki, H. Taguchi, K. Namba, and M. Yoshida. 2004. β-Helix is a likely core structure of yeast prion Sup35 amyloid fibers. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 315:739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bennett, A. E., C. M. Rienstra, M. Auger, K. V. Lakshmi, and R. G. Griffin. 1995. Heteronuclear decoupling in rotating solids. J. Chem. Phys. 103:6951–6958. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishii, Y. 2001. 13C-13C dipolar recoupling under very fast magic angle spinning in solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance: applications to distance measurements, spectral assignments, and high-throughput secondary-structure determination. J. Chem. Phys. 114:8473–8483. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morcombe, C. R., V. Gaponenko, R. A. Byrd, and K. W. Zilm. 2004. Diluting abundant spins by isotope edited radio frequency field assisted diffusion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:7196–7197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takegoshi, K., S. Nakamura, and T. Terao. 2001. 13C-1H dipolar-assisted rotational resonance in magic-angle spinning NMR. Chem. Phys. Lett. 344:631–637. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wishart, D. S., B. D. Sykes, and F. M. Richards. 1991. Relationship between nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift and protein secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 222:311–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lomakin, A., D. B. Teplow, D. A. Kirschner, and G. B. Benedek. 1997. Kinetic theory of fibrillogenesis of amyloid β-protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:7942–7947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collins, S. R., A. Douglass, R. D. Vale, and J. S. Weissman. 2004. Mechanism of prion propagation: amyloid growth occurs by monomer addition. PLoS Biol. 2:1582–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chan, J. C. C., N. A. Oyler, W. M. Yau, and R. Tycko. 2005. Parallel β-sheets and polar zippers in amyloid fibrils formed by residues 10–39 of the yeast prion protein Ure2p. Biochemistry. 44:10669–10680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roher, A. E., J. D. Lowenson, S. Clarke, C. Wolkow, R. Wang, R. J. Cotter, I. M. Reardon, H. A. Zurcher-Neely, R. L. Heinrikson, and M. J. Ball. 1993. Structural alterations in the peptide backbone of β-amyloid core protein may account for its deposition and stability in Alzheimer's disease. J. Biol. Chem. 268:3072–3083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wishart, D. S., C. G. Bigam, A. Holm, R. S. Hodges, and B. D. Sykes. 1995. 1H, 13C and 15N random coil NMR chemical shifts of the common amino acids. I. Investigations of nearest-neighbor effects. J. Biomol. NMR. 5:67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]