Diabetic ketoacidosis is a state of severe uncontrolled diabetes mellitus caused by severe insulin deficiency. It is characterised by hyperglycaemia, hyperketonaemia, and metabolic acidosis.1 Diabetic ketoacidosis is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus,2 and in Western countries the overall mortality is 5-10%.1-3 Common precipitating causes include infection and inadequate dose of insulin resulting from non-adherence, failure to follow “sick day” rules (advice on increasing insulin during intercurrent illness), and poor injection technique.4 We have recently encountered two patients with recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis caused by unrecognised difficulty in switching from one type of prefilled insulin injection device to another.

Case reports

Case 1

A 68 year old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus was admitted to hospital with critically ischaemic feet. A vascular opinion deemed the right foot to be unsalvageable and an emergency below knee amputation was performed. Postoperatively the patient was stable and restarted injecting insulin—twice daily subcutaneous NovoMix 30 insulin (NovoNordisk) via a FlexPen. Subsequently he developed fever, vomiting, and raised fingerstick glucose readings. No sepsis was identified. Venous plasma glucose concentration was 20.9 mmol/l (non-diabetic random glucose < 11 mmol/l), and urinary ketones were present. Arterial blood gas analysis showed a metabolic acidosis, and diabetic ketoacidosis was diagnosed. The patient was treated with intravenous insulin, fluid, and antibiotics. The hyperglycaemia and acidosis resolved.

Magnetic resonance angiography showed a severely stenosed left superficial femoral artery with poor run-off. In view of continued critical ischaemia, following metabolic stabilisation the patient underwent exploration of his left lower limb vasculature and subsequent below knee amputation. Postoperatively he was metabolically stable. His intravenous insulin was stopped, and he restarted injecting subcutaneous insulin. During the following day, his fingerstick blood glucose readings rose. Venous plasma glucose was 24.7 mmol/l with high levels of urinary ketones and a profound metabolic acidosis. Diabetic ketoacidosis was diagnosed and corrected with intravenous insulin and fluid.

Consultation with the diabetes team and a detailed history showed that the insulin delivery device had recently been changed from a NovoPen 3 to a FlexPen (fig 1). Examination of the injection technique showed that instead of depressing the FlexPen plunger to expel insulin, the patient rewound the dial in an attempt to deliver the insulin dose, resulting in no insulin being given (fig 2). Appropriate education resulted in the patient achieving satisfactory glucose concentrations while continuing to inject twice daily NovoMix 30 with a FlexPen.

Fig 1.

Insulin injection devices: FlexPen (top) and NovoPen 3 (bottom)

Fig 2.

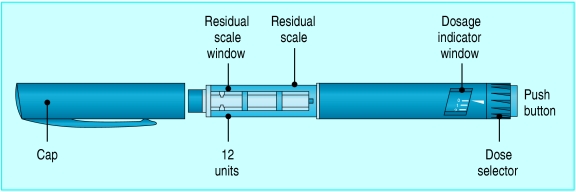

To administer insulin with the FlexPen, the dose is measured by dialling the appropriate number of units on the dose selector. The button is pushed to expel insulin via a needle attached to the clear barrel of the device. “Reverse dialling” of the dose selector does not expel insulin

Case 2

A 17 year old boy who had type 1 diabetes for five years was admitted with ketosis and hyperglycaemia. He had had three episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis during the previous month. On each occasion he had responded to intravenous insulin and intravenous fluids. He had received advice about sick day rules, increasing the insulin dose, and contacting the diabetes team immediately if ketosis recurred. He was injecting NovoRapid insulin (NovoNordisk) via FlexPen with meals, and Levemir insulin (NovoNordisk) by NovoPen 3 twice daily. During this latest admission, examination of his injection technique showed that the patient was trying to inject insulin by “reverse dialling” with both the FlexPen and the NovoPen 3. Although this delivered Levemir insulin through the NovoPen 3, it did not deliver NovoRapid via the FlexPen. The patient was instructed to inject insulin only by depressing the plunger of both pen devices. His hyperglycaemia and ketosis rapidly settled. He has not needed further admission during the ensuing six months.

Discussion

Standard 8 of England's National Service Framework for Diabetes5 recommends that patients should be involved in the care of their diabetes when admitted to hospital. This helps maintain autonomy and may also achieve better glycaemic control than if blood glucose testing and insulin administration are left to busy ward nurses. Insulin injection devices include a range of pen injectors that have proved popular and are considered easy to use. The variety of devices poses problems, however, for non-specialist healthcare staff, who may be unfamiliar with the injector used by a particular patient.

These two cases highlight that simple differences between insulin devices may lead patients to fail to inject their insulin. Despite previous instruction on how to use their pens, both patients had independently found that reverse dialling of the dose selector on the NovoPen 3 device had resulted in insulin injection. Both patients had mistakenly assumed that the same technique would deliver insulin from the FlexPen. We suspect that other patients may try this reverse dialling technique, potentially compromising glycaemic control and running the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis. We have informed the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency of this issue.

Non-specialist staff did not recognise faulty injection technique as the cause of hyperglycaemia and ketosis, resulting in searches for occult infection and suspicion of non-adherence to insulin therapy. Adequate instruction is essential for all patients whose injection devices are changed. This education should include direct observation of an injection to ensure full understanding and a reminder that the described technique is the only safe way to use the injection device. Similarly, injection technique should be reviewed carefully in all patients presenting with diabetic ketoacidosis. In addition, we recommend that warnings about the hazards of incorrect injection technique should be included in the information about all insulin pen devices.

Patients changing their insulin pen injector may use them wrongly, with potentially fatal consequences

We thank J Scanlon and E Grocott for allowing us to report these cases and NovoNordisk (UK) for permission to use the diagram (adapted) for figure 2.

Contributors: VRB and NM wrote the first draft. EI and EH identified reverse dialling as the cause of the recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis. All authors contributed to the management of the patients and to the final draft of the manuscript. DJ is guarantor.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Krentz A, Nattrass M. Acute metabolic complications of diabetes: diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar non-ketotic hyperglycaemia and lactic acidosis. In: Pickup JC, Williams G. Textbook of diabetes 1. 3rd edn. Oxford: Blackwell, 2003.

- 2.Dunger DB, Sperling MA, Acerini CL, Bohn DJ, Daneman D, Danne TP, et al. European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology/Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Society consensus statement on diabetic ketoacidosis in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2004;113: e133-e140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basu A, Close CF, Jenkins D, Krentz AJ, Nattrass M, Wright AD. Persisting mortality in diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabet Med 1993;10: 282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Diabetes Association. Hyperglycemic crises in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27: S94-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health. National service framework for diabetes: delivery strategy. London: DoH, 2002.