Abstract

The cellular protein p32 is a multifunctional protein, which has been shown to interact with a large number of cellular and viral proteins and to regulate several important activities like transcription and RNA splicing. We have previously shown that p32 regulates RNA splicing by binding and inhibiting the essential SR protein ASF/SF2. To determine whether p32 also functions as a regulator of splicing in virus-infected cells, we constructed a recombinant adenovirus expressing p32 under the transcriptional control of an inducible promoter. Much to our surprise the results showed that p32 overexpression effectively blocked mRNA and protein expression from the adenovirus major late transcription unit (MLTU). Interestingly, the p32-mediated inhibition of MLTU transcription was accompanied by an approximately 4.5-fold increase in Ser 5 phosphorylation and an approximately 2-fold increase in Ser 2 phosphorylation of the carboxy-terminal domain (CTD). Further, in p32-overexpressing cells the efficiency of RNA polymerase elongation was reduced approximately twofold, resulting in a decrease in the number of polymerase molecules that reached the end of the major late L1 transcription unit. We further show that p32 stimulates CTD phosphorylation in vitro. The inhibitory effect of p32 on MLTU transcription appears to require the CAAT box element in the major late promoter, suggesting that p32 may become tethered to the MLTU via an interaction with the CAAT box binding transcription factor.

The large subunit of mammalian RNA polymerase II (Pol II) has a carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) composed of 52 tandem repeats of the heptapeptide YSPTSPS. The CTD is extensively phosphorylated, especially at the Ser 2 and Ser 5 positions, resulting in the formation of two forms of Pol II, the hypophosphorylated Pol IIA and the hyperphosphorylated Pol IIO. The phosphorylation of different serines in CTD appears to predominate at different phases of transcription. Thus, during the assembly stage Pol IIA is preferentially recruited to the promoter. The transition from initiation to elongation is accompanied by a phosphorylation at Ser 5, whereas the phosphorylation pattern changes to Ser 2 during the elongation phase of transcription. The Ser 2 phosphorylation level increases as Pol II moves further from the promoter, rendering Pol II more processive (8). At the end of the transcription cycle the CTD phosphatase FCP1 regenerates Pol IIA by dephosphorylation of CTD. A Ser 5-specific phosphatase, SCP1, may play a role in the transition from initiation to processive elongation by removing Ser 5 phosphorylation (50). The phosphorylated status of CTD is important for Pol II function since CTD interacts with factors needed for capping, splicing, and polyadenylation of the nascent transcript. For example, Ser 5 phosphorylation, which is catalyzed by the CDK7 subunit of the general transcription factor TFIIH, facilitates recruitment of the enzyme complex required for capping the nascent transcript (42). Similarly, the switch to Ser 2 phosphorylation, which is catalyzed by the CDK9 subunit of elongation factor P-TEFb, may aid in the recruitment of factors important for coupling transcription and RNA-processing events (2, 36).

Clearly, an important way to regulate transcription would be through control of kinases and phosphatases involved in the cyclic phosphorylation of CTD. There are multiple examples of proteins that appear to affect Pol IIO turnover. For example, the RAP74 component of TFIIF stimulates both FCP1 and SCP1 dephosphorylation of Ser 2 and Ser 5 (5, 17, 50), whereas the peptidyl-propyl isomerase Pin1 inhibits ongoing transcription by blocking Ser 2 dephosphorylation (49). Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Tat inhibits FCP1-induced dephosphorylation as well as stimulating the kinase activity of CDK9/P-TEFb (1, 16), whereas BRCA1 inhibits Ser 5 phosphorylation by blocking the ATP binding site in CDK7/TFIIH (32).

Our work has focused on the ubiquitously expressed cellular protein p32/HABP1/gC1q-R (hereafter referred to as p32), which was originally isolated as a protein tightly associated with the essential cellular splicing factor ASF/SF2 (19). p32 is a multifunctional protein that is localized at the cell surface and in the mitochondria, cytoplasm, and nucleus in various cell types. The p32 protein has been shown to interact with a large number of cellular, viral, and bacterial proteins. In some cases the interaction between p32 and a target protein has been shown to regulate important cellular activities controlling gene expression. For example, p32 interaction with the SR protein ASF/SF2 inhibits ASF/SF2 as a splicing factor (39). p32 also promotes the accumulation of genomic HIV transcripts by inhibiting HIV splicing (52). The interaction of p32 with the HIV Rev protein promotes nucleus-to-cytoplasm export of unspliced HIV RNA (25). Also, several reports have described a role for p32 in transcription. The interaction between p32 and HIV-1 Tat (51), Epstein-Barr virus EBNA-1 (46), and herpes simplex virus orf73 (13) has been shown to stimulate transcription in model reporter constructs, whereas p32 interaction with the cellular transcription factor CBF/NF-Y (6) or the gammaherpesvirus 68 M2 protein (22) has been shown to result in an repression of transcription.

In a previous study Matthews and Russell showed that the adenovirus core protein V interacts with the p32 protein, particularly in the nuclei of cells in a late stage of infection (31). We have previously shown that, in vitro and in transient-transfection experiments, p32 functions as a regulator of RNA splicing by binding to ASF/SF2 and inhibiting ASF/SF2 phosphorylation (39). Here we constructed a recombinant adenovirus that expresses p32 from an inducible promoter to determine whether p32 functions as a regulator of splicing of mRNAs derived from the adenovirus major late transcription unit (MLTU) also during a virus infection. Much to our surprise, the results showed that overexpression of p32 efficiently reduced mRNA accumulation from the MLTU. This decrease in mRNA accumulation was accompanied by an approximately twofold reduction in the efficiency of Pol II transit from the initiation phase to processive elongation. The p32-mediated suppression of MLTU transcription was accompanied by an accumulation of both Ser 5- and Ser 2-hyperphosphorylated Pol II. The fraction of Pol II molecules that were able to reach the end of the transcription unit had an approximately 4.5-fold increase in Ser 5 phosphorylation and a 2-fold increase in Ser 2 phosphorylation, suggesting that the cyclic changes in CTD phosphorylation expected to occur during processive elongation were disturbed. Further, we show that p32 in vitro stimulated glutathione S-transferase (GST)-CTD phosphorylation at both Ser 2 and Ser 5. We also show that the inhibitory effect of p32 on MLTU transcription was specific and requires the CAAT box element in the adenovirus major late promoter (MLP). This element binds the cellular transcription factor CBF/NF-Y. Since p32 recently was shown to interact with CBF/NF-Y (6), this result suggests that p32-induced hyperphosphorylation of Pol II may require the tethering of p32 to the MLP via an interaction with CBF/NF-Y.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of a recombinant adenovirus expressing a Flag-tagged p32 protein.

Transfer plasmid pAdTetTrip(Flag)-p32 was constructed by isolating the BamHI fragment encoding the p32 protein from pAdCMV-p32 (39) and cloning it into the unique BamHI site in the pAdTetTripLac-Bam vector (4). Plasmid pAdTetTrip(Flag)-p32 was reconstructed into a recombinant adenovirus essentially as described by Stow (44). Briefly, a vector arm was produced by double digestion of genomic adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) dl309 DNA with XbaI and ClaI, followed by sucrose gradient purification of the long right-hand 3.71- to 100-unit genomic fragment. Recombinant viruses were generated by in vivo recombination. Thus, 5 μg of pAdTetTrip(Flag)-p32 DNA was mixed with 1 μg of Ad5 dl309 vector arm and cotransfected by the calcium phosphate coprecipitation technique into 293 cells (12). Plaques typically appeared 5 to 6 days posttransfection. Recombinant viruses were verified by restriction enzyme cleavage. One positive plaque was selected and purified by a second round of the plaque assay. The final reporter virus was named AdTTflag-p32, and Flag-p32 protein expression was confirmed by Western blot analysis. The activator virus AdCMVrtTA has previously been described (34).

Plasmids and recombinant proteins.

Plasmid pCMV-p32 and the empty cytomegalovirus (CMV) control vector pCMV-BamHI have previously been described (39). Reporter plasmids pTrip-CAT and pTrip-CAT (CCCAT), which encode the bacterial chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene under the transcriptional control of the adenovirus MLP, were kindly provided by Anders Sundqvist and Catharina Svensson. Luciferase reporter plasmids containing different parts of the human tripeptidyl-peptidase II promoter in the pGL3-basic vector (Promega) have previously been described (23). Plasmid pGEX2T-CTD, which encodes the carboxy-terminal domain (52 tandem repeats and the 10 carboxy-terminal amino acids) from the large subunit of RNA polymerase II from mice, was kindly provided by Anne-Christine Ström. The His-p32 and the GST-CTD proteins were expressed and purified from Escherichia coli using a standard Ni column and glutathione-Sepharose chromatography (Amersham Bioscience), respectively.

Transfection and CAT ELISA.

293 ATCC cells were grown on 6-cm plates in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% newborn calf medium (NCS). At 40 to 60% confluence, transfections were done using the FuGene6 transfection system (Roche) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The amount of reporter plasmid pTrip-CAT or pTripCAT(CCCAT) was kept constant (1 μg), whereas the amount of the plasmid expressing p32, pCMV-p32, was increased (0 to 1 μg). An empty CMV vector was used to keep a total amount of 2 μg of DNA. The cells were harvested at 24 to 36 h posttransfection, washed in phosphate-buffered saline and lysed according instructions with the CAT enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Roche). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method, equal amounts of cell extract were analyzed by CAT ELISA (Roche), and the absorbances of the samples were measured at 405 nm.

Transfection and luciferase assay.

Transfection of 293 ATCC cells was made as described above except that 3-cm plates were used. Constant amounts of luciferase reporter plasmids (1 μg) were transfected with or without 0.2 μg pCMV-p32. An empty CMV vector was used to keep the total amount of DNA at 1.2 μg. Cells were harvested at 48 h posttransfection, washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed in 100 μl luciferase lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100). The luciferase activity was determined after addition of 50 μl luciferase assay substrate (5.0 mg/ml DTT, 0.20 mg/ml coenzyme A [Sigma], 0.5 mg/ml beetle luciferin (Promega), 0.29 mg/ml ATP, 20 mM Tricine, pH 7.8, 1.0 mM MgCO3, 2.6 mM MgSO4, and 100 μM EDTA) using a Luminoscan RT (Labsystems). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method, and equal amounts of extract were assayed.

Cell lines and infections.

293 ATCC cells were grown on 6-cm plates in DMEM supplemented with 10% NCS. At 80 to 90% confluence, cells were washed with DMEM without serum and coinfected with a 2-ml DMEM-2% NCS inoculum containing 5 focus-forming units (FFU)/cell of AdTTflag-p32 and activator virus AdCMVrtTA (34). The virus inoculum was removed after a 1-h incubation at 37°C. Cells were washed two times with fresh DMEM and then incubated in 4 ml DMEM-10% NCS with or without 4 μM doxycycline for approximately 20 to 22 h.

Western blot analysis.

Protein extracts were prepared at 20 hpi (for Fig. 1) and at 8 and 22 hpi (for Fig. 3) by lysis of cells with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) or at 22 hpi (for Fig. 9) by making small-scale nuclear extracts (21). Extracts were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose filter by electroblotting. Membranes were blocked in TBS-T (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Tween 20) with 5% dry milk, incubated overnight with primary antibody, washed five times in TBS-T, and incubated further for 2 h with a secondary antibody. The membrane was finally washed five times with TBS-T, and proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence with ECL Western blot reagent as described by the manufacturer (Amersham Bioscience). The primary antibodies were used at dilutions of 1:500 for anti-Prage (40), 1:1,000 for actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 1:250 for N20 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 1:250 for 8WG16 antibody (Covance), 1:250 for H5 antibody (Covance), 1:250 for H14 antibody (Covance), and 1:2,000 for anti-Flag M2 antibody (Sigma). To increase the sensitivity, rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin M antibody (1:1,000; Covance) was added together with the H5 and the H14 primary antibodies. Secondary antibodies were used at dilutions of 1:2,000 for rabbit anti-mouse antibody-horseradish peroxidase (HRP; DAKO), 1:2,000 for swine anti-rabbit antibody-HRP (DAKO), and 1:1,000 for bovine anti-goat antibody-HRP (DAKO).

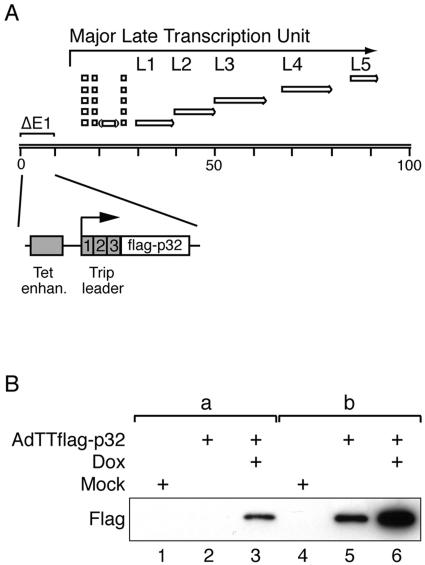

FIG. 1.

Induction of Flag-p32 expression. (A) Schematic illustration showing the structure of recombinant virus AdTTflag-p32. The tetracycline-regulatable gene cassette is located at the left end of the viral genome, replacing all of the E1A region and most of the E1B region. The nucleotide sequence of this construct is available upon request. The structure of the coterminal mRNA families derived from the major late transcription unit is also indicated. (B) Western blot analysis of Flag-p32 expression in AdTTflag-p32-infected 293 cells harvested 20 hpi. In groups a (lanes 1 to 3) and b (lanes 4 to 6), 0.4 μg and 1.6 μg of extract, respectively, was separated by SDS-PAGE and probed with an anti-Flag monoclonal antibody. Note that cells infected with the AdTTflag-p32 virus were also coinfected with an equal amount (5 FFU per cell) of the activator virus AdCMVrtTA. The coinfection protocol is necessary in order to provide the reverse tetracycline activator protein that drives Flag-p32 expression (34).

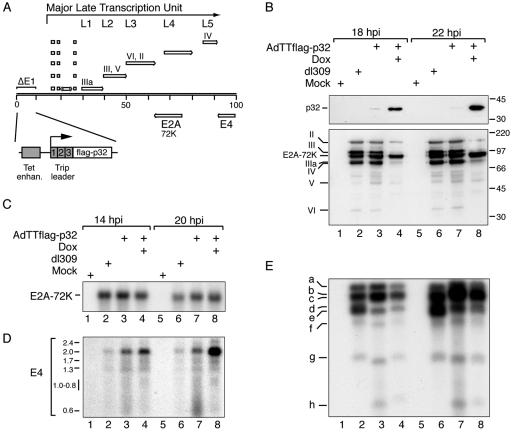

FIG. 3.

p32 overexpression blocks gene expression from the MLTU. (A) Schematic illustration showing the position of MLTU units L1 to L5, regions E2A and E4, with the positions of the coding regions for proteins relevant for this study indicated. AdTTflag-p32-infected 293 cells were harvested at the time points indicated, and protein (B), total cytoplasmic RNA (C and D), and viral DNA (E) were isolated and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Western blot analysis using an anti-Flag monoclonal antibody (upper part) or an antibody directed against late viral proteins (lower part). The positions of the Flag-p32 protein, late structural proteins, and the E2A-72K DNA binding protein are indicated on the left. (C) Northern blot analysis using a 32P-labeled probe specific for region E2A. (D) Northern blot analysis using a 32P-labeled probe specific for region E4. Sizes of the RNA classes are given in kilobases (47). (E) Southern blot analysis of HindIII-digested low-molecular-weight DNA (fragments a to h) using a 32P-labeled probe prepared by random priming of dl309 virion DNA.

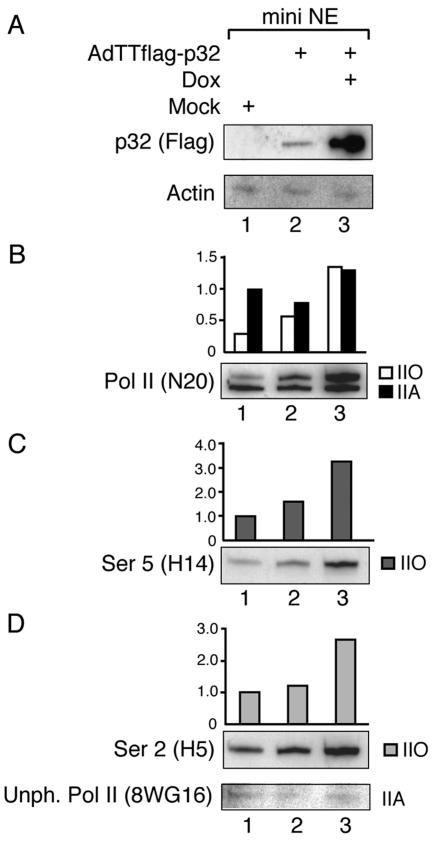

FIG. 9.

Overexpression of Flag-p32 increases RNA Pol IIO hyperphosphorylation. Mini-nuclear extracts were prepared from AdTTflag-p32-infected 293 cells 22 hpi or control cells and subjected to Western blot analysis using a panel of antibodies. Note that cells infected with the AdTTflag-p32 virus were also coinfected with an equal amount (5 FFU per cell) of the activator virus AdCMVrtTA. The coinfection protocol is necessary in order to provide the reverse tetracycline activator protein that drives Flag-p32 expression (34).

Northern blot analysis.

Total cytoplasmic RNA was prepared by lysis of cells with IsoB-NP-40 (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.65% NP-40), followed by two rounds of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction and one extraction with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol and precipitation with isopropanol. Two micrograms of RNA was separated on a 1% agarose gel containing 2.2 M formaldehyde, transferred to a nitrocellulose filter, and hybridized with a DNA probe 32P labeled by random priming as described previously (3). The Ad2 HindIII I fragment was used as a probe to detect L1 mRNAs, the 63.8- to 64.9-map-unit BstEII fragment was used for analysis of E2A mRNA, and the right-terminal HindIII fragment was used to detect E4 mRNAs.

Southern blot analysis.

Low-molecular-weight viral DNA was prepared at 18 and 22 h postinfection (hpi) from infected 293 ATCC cells by Hirt extraction (14). An equal fraction of the purified DNA was digested with HindIII, and the resulting fragments were separated on 1% agarose gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose filter, and hybridized at 68°C in 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 5× Denhardt solution, 1% SDS, and 100 μg single-stranded DNA/ml (3) to a 32P-labeled Ad5 dl309 virion DNA probe labeled by random priming.

ChIP assay.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and PCRs were performed essentially as described in the Abcam catalogue (2002/2003; www.abcam.com). Briefly, at 22 hpi cells were cross-linked directly on the culture dish by addition of formaldehyde to a final concentration of 1%. Cell nuclei were isolated and sonicated to obtain chromatin with an average size of approximately 500 base pairs. The chromatin samples were immunoprecipitated with antibody N20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 8WG16 (Covance), H5 (Covance), or H14 (Covance). The cross-linking was reversed, the DNA was purified by phenol extraction, and the precipitated DNA was quantified after PCR amplification using one of three PCR primer pairs: primer pair A, which amplifies a 314-base-pair fragment spanning the MLP (forward primer, 5′-TCCTCACTCTCTTCCGCATC-3′; reverse primer, 5′-TACGTGCAGCTAAACATCGC-3′); primer pair B, which amplifies a 350-base-pair fragment covering the translational start codon for the L1 52,55K protein (forward primer, 5′-TAGCCGGAGGGTTATTTTCC-3′; reverse primer, 5′-CTCCAAGTCCAGGTAGTGCC-3′); or primer pair C, which amplifies a 288-base-pair fragment located 800 base pairs upstream of the L1 poly(A) signal (forward primer, 5′-CTGCTAATAGCGCCCTTCAC-3′; reverse primer, 5′-GTTAAGGCTCACGCTCTGCT-3′). The linear range for each primer pair was determined empirically.

In vitro kinase assay.

Increasing amounts (0 to 2,400 pmol) of His-p32 were preincubated at 30°C for 30 min with 0.5 μg HeLa nuclear extracts (35). Recombinant GST-CTD (10 pmol) was added, and the samples were further incubated for 2 min at room temperature. The kinase buffer used contained 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 130 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM ATP. The samples were run on an SDS-7% PAGE gel under reducing conditions and transferred to a nitrocellulose filter by electroblotting. Proteins were detected by Western blot analysis.

RESULTS

Construction of a recombinant adenovirus overexpressing p32 from a tetracycline-regulatable promoter.

To be able to further dissect the role of p32 in vivo, we constructed recombinant adenovirus AdTTflag-p32 (schematically shown in Fig. 1A), expressing the p32 protein fused to an amino-terminal Flag epitope tag and under the transcriptional control of a tetracycline-regulatable promoter (34). The experimental approach is based on a double-infection strategy where equal FFU of a reporter virus and an activator virus are mixed and used for infection. The reporter virus AdTTflag-p32 and the activator virus AdCMVrtTA were used to infect 293 ATCC cells, and transcription of the Flag-p32 gene was activated by addition of doxycycline to the culture medium. At 20 hpi, cells were lysed and extracts subjected to Western blot analysis using a Flag-specific antibody. As shown in Fig. 1B, treatment of infected 293 cells with doxycycline resulted in a high level of Flag-p32 expression (lane 3 and 6). The background expression of Flag-p32 was low (lane 2) but clearly detectable in larger amounts of cell extract (lane 5), in the absence of inducer. This result was not unexpected since we have previously observed a low basal activity in our inducible vector systems in 293 cells, which is caused by the promiscuous E1A transcriptional activator protein, which activates the minimal promoter element in the Tet promoter (10, 33).

Overexpression of the p32 protein decreases the steady-state amount of RNA transcribed from the adenovirus MLTU L1 region.

We have previously shown that the p32 protein enhances adenovirus IIIa splicing in vitro and in transient-transfection assays by inhibiting phosphorylation of the critical ASF/SF2 protein (39). To determine whether p32 functions as a regulator of alternative splicing during a lytic infection, we used the AdTTflag-p32 virus to overexpress the Flag-p32 protein in 293 cells. Protein expression was induced from the start of infection, and total cytoplasmic RNA from induced or control infections was prepared at 14 or 20 hpi and analyzed by Northern blotting (Fig. 2B) with a probe designed to detect the alternatively spliced mRNAs from the L1 region (Fig. 2A).

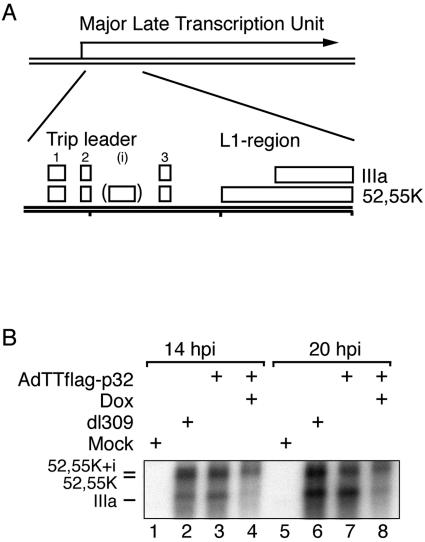

FIG. 2.

p32 overexpression blocks L1 mRNA accumulation. (A) Schematic illustration showing the spliced structure of the 52,55K and the IIIa mRNAs expressed from region L1. (B) Northern blot analysis of total cytoplasmic RNA prepared from AdTTflag-p32-infected cells at the indicated time points. RNA was transferred to a nitrocellulose filter and hybridized with a 32P-labeled probe specific for region L1. Note that cells infected with the AdTTflag-p32 virus were also coinfected with an equal amount (5 FFU per cell) of the activator virus AdCMVrtTA. The coinfection protocol is necessary in order to provide the reverse tetracycline activator protein that drives Flag-p32 expression (34).

As shown in Fig. 2B, AdTTflag-p32-infected cells induced to express p32 suppressed IIIa mRNA accumulation. However, the most pronounced effect was the dramatic decrease in the total L1 mRNA accumulation (lanes 4 and 8) compared to the uninduced (lanes 3 and 7) or wild-type-infected cells (lanes 2 and 6). A quantification of the results suggests that p32 overexpression caused an approximately 10-fold reduction in total L1 mRNA accumulation at 20 hpi.

The inhibitory effect of p32 on MLTU gene expression is selective.

The IIIa mRNA is expressed as part of the MLTU (Fig. 3A). To determine whether other genes expressed from the MLTU were similarly reduced in expression, we analyzed late viral protein expression in a Western blot assay using an antibody directed against native virus particles (40). As shown in Fig. 3B, induction of p32 overexpression resulted in a dramatic inhibition of accumulation of all polypeptides derived from the MLTU (II, III, IIIa, IV, V, and VI) at both 18 hpi and 22 hpi (compare lanes 3 and 4 with 7 and 8). This result is compatible with the conclusion that p32 has a general inhibitory effect on MLTU transcription and does not block only L1 mRNA accumulation. Interestingly, the polyclonal antibody also detects the E2A-72K DNA binding protein (Fig. 3B). In contrast to the late structural proteins encoded by the MLTU, E2A-72K protein expression was not negatively affected by p32 overexpression. Since the antibody used in this experiment (40) was made against purified virions, it was not expected to recognize the E2A-72K protein. To verify the result, we used Northern blotting to analyze E2A-72K mRNA expression. As shown in Fig. 3C, p32 overexpression did not have much of an adverse effect on E2A-72K mRNA expression (lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8). To further demonstrate that p32 overexpression did not have a general inhibitory effect on adenovirus gene expression, we analyzed E4 mRNA expression by Northern blotting. As shown in Fig. 3D, p32 overexpression did not repress E4 mRNA expression. In fact, p32 overexpression resulted in an increase in the accumulation of the 2-kb E4 mRNA species (lane 8). Interestingly, this increase is accompanied by a decrease in the accumulation of shorter E4 mRNAs (0.6- to 1.0-kb mRNAs), suggesting that p32 overexpression may have an effect on E4 pre-mRNA splicing.

p32 overexpression does not block viral DNA replication.

It is possible that the effect of p32 on MLTU expression was indirect, resulting from a dramatic inhibitory effect of p32 overexpression on viral DNA replication. Thus, efficient transcription from the MLTU requires that the viral DNA has started to replicate (45). To investigate whether the reduced accumulation of mRNA from the MLTU in p32-overexpressing cells was due to a restriction of infected cells from entering the late phase of the lytic cycle, we determined the efficiency of viral DNA replication by Southern blot analysis at 18 hpi and 22 hpi. As shown in Fig. 3E, the efficiency of viral DNA replication was slightly delayed in p32-overexpressing cells, with approximately 40% accumulation of DNA at 18 hpi (lanes 3 and 4). At the later time point (22 hpi) the p32-overexpressing cells had recovered even further, with an approximately 60% efficiency of DNA accumulation compared to the wild type (lanes 7 and 8).

Taken together the results presented in Fig. 3 suggest that p32 overexpression does not significantly affect viral DNA replication or E2A-72K mRNA and protein expression. Therefore, the large effect of p32 overexpression on MLTU protein (Fig. 3B) and mRNA (Fig. 2B) expression cannot be easily explained by a defect in viral DNA replication (Fig. 3E).

p32-mediated inhibition of adenovirus major late transcription requires the CAAT box element in the major late promoter.

The CAAT box element in the adenovirus MLP has been shown to be important for efficient major late mRNA transcription (43). The CAAT box binds the cellular transcription factor CBF/NF-Y, which functions as a strong activator of the MLP in vitro (27). In a recent study Chattopadhyay et al. showed that p32 inhibits CBF/NF-Y-activated transcription of the α2(1) collagen promoter (6). This finding raised the interesting possibility that p32 overexpression reduced gene expression from the MLTU (Fig. 2 and 3) because of a p32-mediated effect on MLP transcription.

To test this hypothesis, MLP constructs with a mutation in the CAAT box were fused to a CAT reporter gene and the effect of p32 cotransfection on CAT expression was quantified using CAT ELISA. As shown in Fig. 4A, cotransfection of the wild-type MLP construct and increasing amounts of a plasmid constitutively expressing p32 resulted in an approximately 65% reduction of CAT activity (bars 6 to 10). Introducing a point mutation in the CAAT box caused as expected a dramatic reduction of basal CAT expression (compare bars 6 and 11). Interestingly, cotransfection of an increasing amount of a plasmid expressing p32 was not inhibitory in the absence of a functional CAAT box (bars 11 to 15). To further test the dependence on a CAAT box for p32-mediated inhibition of reporter gene expression, we cotransfected plasmid pCMV-p32 together with luciferase reporter constructs under the transcriptional control of the human tripeptidyl-peptidase II promoter (Fig. 4B). The tripeptidyl-peptidase II promoter contains two inverted CAAT boxes that previously have been demonstrated to bind CBF/NF-Y (23). As shown in Fig. 4C, clone 174, which contains two CAAT boxes, showed a high basal luciferase activity that was dramatically reduced in pCMV-p32-cotransfected cells (compare bars 9 and 10). Plasmids lacking either the downstream (clone 104; Fig. 4B) or the upstream (clone 130; Fig. 4B) CAAT boxes showed a dramatically reduced basal luciferase activity (Fig. 4C, bars 3 and 7) compared to the full-length clone (bar 9). Importantly, these clones were subjected to an approximately twofold p32-mediated repression (compare bars 3 and 4 with 7 and 8). In contrast, clone 118 (Fig. 4B), which lacks both CAAT boxes showed an approximately equal basal activity as clones 104 or 130. However, this clone was not repressed by pCMV-32 cotransfection (Fig. 4C, bar 6). Collectively, these results suggest that the inhibitory effect of p32 requires a CAAT box and may require the CAAT box binding transcription factor CBF/NF-Y. Consequently, the inhibitory effect of p32 on MLTU mRNA expression may be mediated by CBF/NF-Y.

FIG. 4.

p32 inhibition of major late promoter activity requires the CAAT box. (A) Increasing amounts of pCMV-p32 (0.05, 0.1, 0.5, or 1 μg) as well as an empty CMV control vector (−) were cotransfected together with a constant amount (1 μg) of the wild-type reporter construct pTrip-CAT (bars 6 to 10), CAAT box mutant pTripCAT (CCCAT) (bars 11 to 15), or no CAT-expressing plasmid (bars 1 to 5). Cell extracts were prepared between 24 and 36 h posttransfection, and CAT protein expression was quantitated by CAT ELISA (Boehringer Mannheim). (B) Schematic illustration showing the structures of the tripeptidyl-peptidase II promoter luciferase constructs (23). The full-length construct (174) contains the two inverted CAAT boxes and the initiator (Inr) element found in the wild-type promoter (23), whereas constructs 104 and 130 contained only one of the CAAT boxes. Construct 118 lacks both CAAT boxes, and the empty pGL3-basic vector was used as a negative control (−). (C) A constant amount of the different luciferase constructs (1 μg) was cotransfected with an empty CMV control vector (0.2 μg; black bars) or with pCMV-p32 (0.2 μg; gray bars). Cell extracts were prepared at 48 h posttransfection, and luciferase protein expression was quantified in a Luminoscan RT (Labsystems). The results represent means ± standard deviations from three independent transfections.

Distribution of Pol II on the MLTU in wild-type-infected cells.

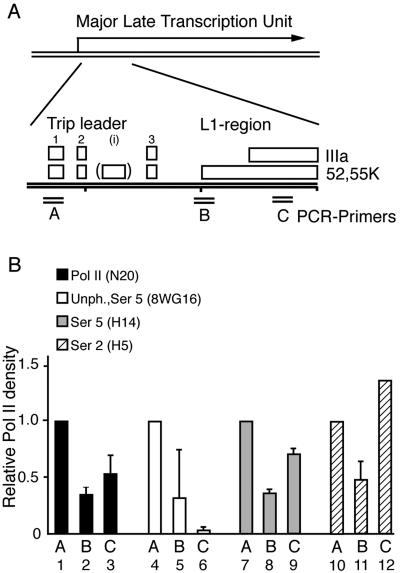

To test if the p32-mediated inhibition of MLP transcription was manifested at the level of assembly of the basal transcription machinery and/or transcription elongation, we used the ChIP assay to analyze the distribution of Pol II on the L1 region. As a starting point we measured the Pol II density in wild-type-infected cells. For this purpose three PCR primer pairs distributed along the 8-kb L1 region were selected (Fig. 5A). PCR primer pair A targets the MLP including the first exon of the tripartite leader. Primer pair B amplifies a region in the middle of the L1 unit, whereas primer pair C targets a sequence approximately 800 base pairs upstream of the L1 poly(A) site.

FIG. 5.

The cyclic phosphorylation of the CTD during a wild-type-adenovirus infection. (A) Schematic figure showing an expansion of the L1 transcription unit with the positions of the spliced tripartite leader segments and the L1 52,55K and IIIa mRNA bodies indicated (for a review see reference 15). The approximate positions of the three PCR primer pairs used in the ChIP assay are indicated. (B) Densities of different phosphorylated forms of RNA pol II along the MLTU L1 region. A panel of four antibodies recognizing either the total number of RNA pol II or different forms of phosphorylated CTD were used in the ChIP assay. The results from the PCR amplifications were quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis and are presented here in relation to the value obtained from PCR primer pair A (promoter proximal), which is set as 1 for each antibody.

To obtain a relative measure of the polymerase density on the L1 region, we used monoclonal antibody N20, which recognizes the amino terminus of the large subunit of Pol II. As shown in Fig. 5B, Pol II was enriched approximately twofold at the MLP (bar 1) in wild-type-dl309-infected cells compared to Pol II distribution at the middle of the L1 unit (bar 2) or towards the end of the L1 gene (bar 3). This result was expected, since it has previously been shown that a large fraction of Pol II initiating transcription at the MLP prematurely terminates transcription (20, 26, 41). It has been well documented that CTD is hypophosphorylated at the stage of preinitiation complex formation (37). Using the 8WG16 antibody, which preferentially recognizes unphosphorylated Ser 2 (for a review see reference 38) and to a lesser extent phosphorylated Ser 5 (8), confirmed that the Pol II loaded at the MLP was Ser 2 hypophosphorylated (Fig. 5B, bar 4). Shortly after initiation of transcription the CTD becomes phosphorylated at Ser 5 (7, 18) and, as expected when the Ser 5-specific H14 antibody was used in the ChIP assay, revealed a strong signal in Ser 5-phosphorylated Pol II at the MLP (Fig. 5B, bar 7). The H14 signal mimicked the Pol II signal (N20) on primer pairs B and C (Fig. 5B), suggesting that the Pol II reaching the end of the L1 unit retained the Ser 5 phosphorylation pattern during the transcription cycle. Efficient transcription elongation is accompanied by an increase in Ser 2 phosphorylation (7, 18). As shown in Fig. 5B, immunoprecipitation with the Ser 2-specific antibody (H5) revealed the highest accumulation of phosphorylated Pol II at the end of the L1 region (compare bars 10 to 12). This increase in Ser 2 hyperphosphorylation was accompanied by a gradual loss of the 8WG16 signal toward the end of the L1 unit (compare bars 4 to 6). Collectively, these results suggest that MLTU transcription during a normal lytic infection appears to respond to the same reversible CTD phosphorylation reactions as reported for some eukaryotic genes.

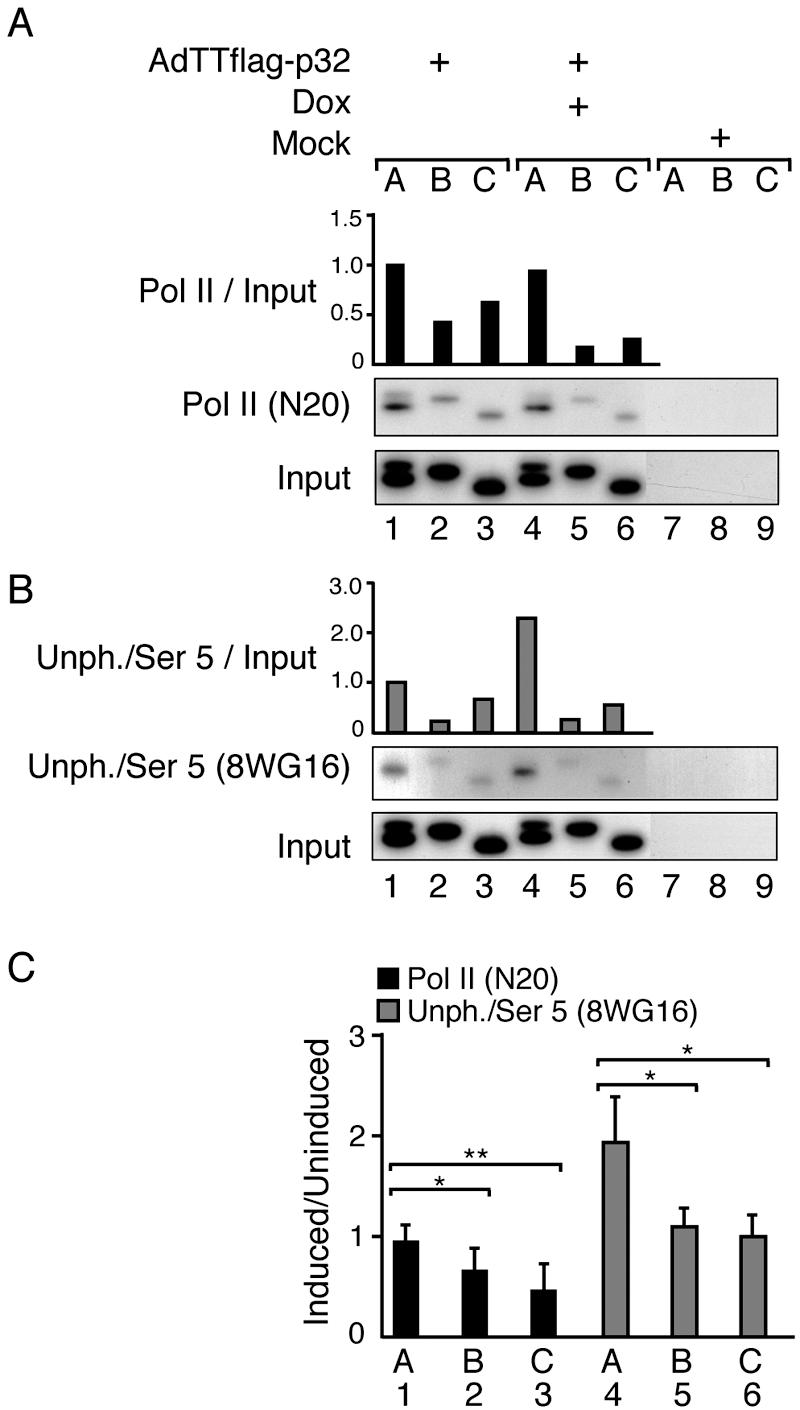

Overexpression of p32 reduces the efficiency of Pol II elongation.

To examine the effect of p32 on Pol II density on the L1 unit, ChIP assays were performed on AdTTp32-infected cells. As shown in Fig. 6A overexpression of Flag-p32 did not significantly alter the total amount of Pol II that was detected at the MLP compared to uninduced cells (lanes 1 and 4). However, the density of Pol II detected in the middle, or at the end, of the L1 unit was significantly reduced in p32-overexpressing cells (compare lanes 2 and 3 to 5 and 6). Thus, in wild-type-infected cells (Fig. 5B, bars 1 to 3) and uninduced AdTTflag-p32-infected cells (Fig. 6A, lanes 1 to 3) only about 50% of the Pol II detected at the MLP reaches the end of the L1 transcription unit. This figure is further decreased in p32-overexpressing cells, resulting in a situation where the Pol II density was decreased to 25% at the end of the L1 unit (Fig. 6A, lanes 5 to 6). This result indicates that overexpression of the p32 protein reduces the efficiency of transcription elongation approximately twofold (Fig. 6C, bars 1 to 3). Taken together, these results suggest that Pol II assembly at the MLP is relatively normal in p32-overexpressing cells (Fig. 6A). However, the processivity of the polymerase is reduced, resulting in an approximately twofold reduction of Pol II molecules that are able to reach the end of the L1 transcription unit (Fig. 6C, bars 1 to 3).

FIG. 6.

p32 overexpression reduces the efficiency of RNA Pol II elongation. AdTTflag-p32-infected 293 cells were fixed 22 hpi, and ChIP assays were performed using antibody N20, which recognizes the amino terminus of the large subunit of RNA Pol II (A), or antibody 8WG16, which detects primarily unphosphorylated CTD and weakly Ser 5-phosphorylated CTD (B). Signals were quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis and normalized against the input DNA, which shows the signal from the chromatin before immunoprecipitation. The signal for the promoter (lane 1) in uninduced cells was set as 1 in the respective panels. The data in panels A and B display one representative experiment each. (C) Ratios of the RNA Pol II density at positions A, B, and C (Fig. 5A) in response to p32 induction. Values represent means ± standard deviations from six (N20) or four (8WG16) independent experiments, with a statistically significant reduction (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01) between indicated comparisons (one-tailed paired t test analysis). Note that cells infected with the AdTTflag-p32 virus were also coinfected with an equal amount (5 FFU per cell) of the activator virus AdCMVrtTA. The coinfection protocol is necessary in order to provide the reverse tetracycline activator protein that drives Flag-p32 expression (34).

We next analyzed whether p32 overexpression affected CTD phosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 6B, using the 8WG16 antibody in the ChIP assay demonstrated an approximately twofold increase in the Pol II signal at the MLP in p32-overexpressing cells (compare lanes 1 and 4). This result was in sharp contrast to the Pol II signal downstream of the transcription initiation site. The 8WG16 signal at chromosomal positions B and C was reduced to levels comparable to that observed in uninduced cells (Fig. 6B, compare lanes 2 and 3 with 5 and 6). Since 8WG16 primarily recognizes CTDs unphosphorylated at Ser 2 and weakly phosphorylated at Ser 5, these results indicate that Pol II assembling at the MLP is either hypophosphorylated or Ser 5 hyperphosphorylated (see below).

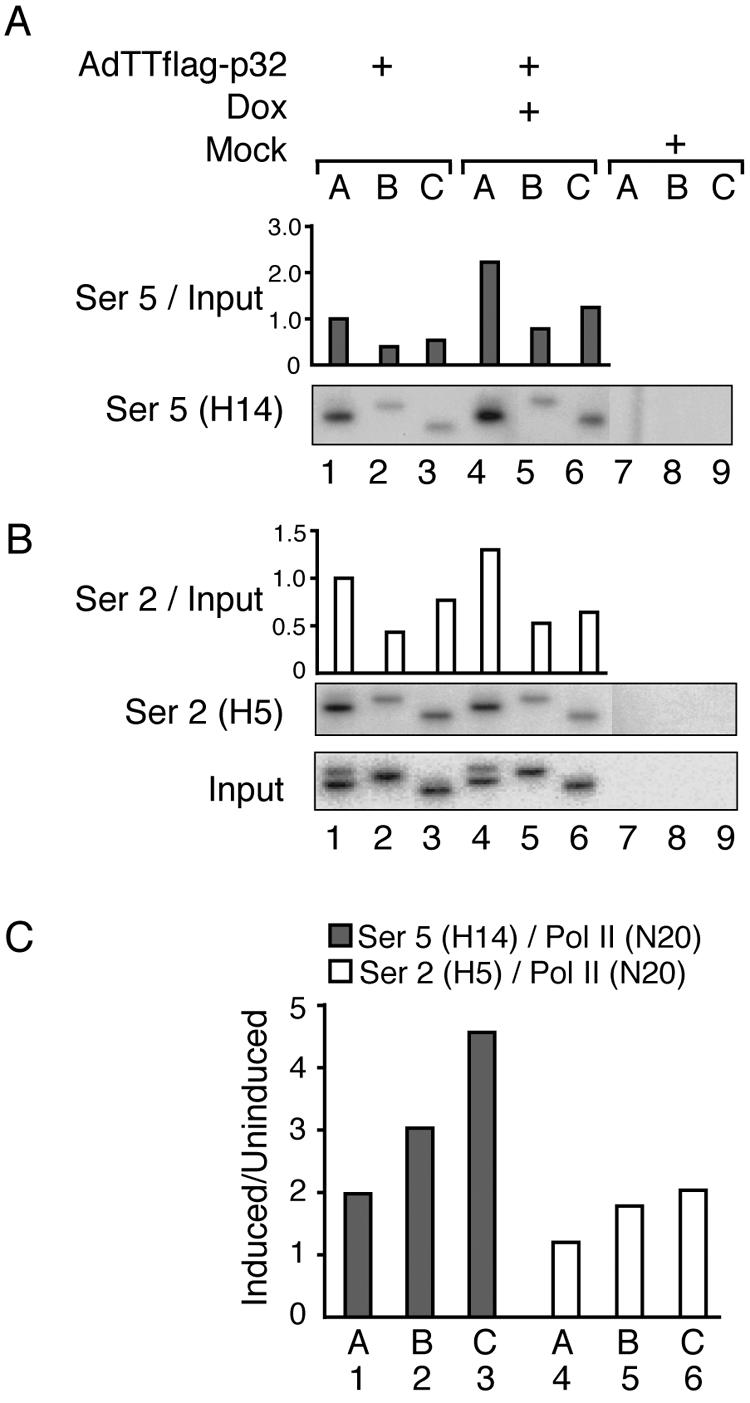

p32 overexpression results in Ser 5 and Ser 2 hyperphosphorylation of CTD.

Next we determined whether the observed defect in elongation could be due to an effect of p32 on CTD phosphorylation. At the promoter CTD is expected to first become phosphorylated at Ser 5. However, on the elongating Pol II Ser 2 phosphorylation of CTD should increase. To determine whether p32 affected Ser 2 or Ser 5 phosphorylation, we used phosphoepitope-specific antibodies H14 (Ser 5) and H5 (Ser 2), respectively. As shown in Fig. 7A, a high level of p32 expression caused a twofold increase in Ser 5 phosphorylation at the promoter site (compare lanes 1 and 4). This increase in phosphorylation was also retained at downstream positions (compare lanes 2 and 3 with 5 and 6), suggesting that the elongating Pol II was Ser 5 hyperphosphorylated. The extent of Ser 2 phosphorylation was essentially the same in uninduced and p32-overexpressing cells (Fig. 7B). However, the results presented in Fig. 7A and B do not take into account the fact that the efficiency of Pol II elongation was slightly reduced in p32-overexpressing cells (Fig. 6C, bars 1 to 3). Thus, taking these changes into account, p32 expression results in a significant increase in both Ser 5 and Ser 2 phosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 7C, the Pol II that initiates transcription already appears to have a twofold increase in Ser 5 phosphorylation compared to uninduced cells. This increase in Ser 5 phosphorylation becomes even more pronounced during the elongation phase, with the Pol II that reaches the end of the L1 transcription unit having an approximately 4.5-fold increase in Ser 5 phosphorylation. Similarly, p32 overexpression caused a twofold increase in Ser 2 phosphorylation of the elongation-associated Pol II that reaches the end of the L1 unit. Collectively, our results suggest that p32 overexpression during a lytic adenovirus infection perturbs the cyclic phosphorylation of CTD and causes an accumulation of hyperphosphorylated Pol II species.

FIG. 7.

p32 overexpression induces CTD hyperphosphorylation. AdTTflag-p32-infected 293 cells were fixed 22 hpi, and ChIP assays were performed using antibody H14, which recognizes Ser 5 phosphorylation (A) or antibody H5, which detects Ser 2-phosphorylated CTD (B). Signals were quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis and normalized against the input DNA, which shows the signal from the chromatin before immunoprecipitation. The signal for the promoter (lane 1) in uninduced cells was set as 1 in the respective panels. The data in panels A and B display the results from one representative experiment. (C) Mean ratio of RNA Pol II density, using Ser 5- or Ser 2-specific antibodies, from several experiments in response to p32 induction divided by the total density of RNA Pol II detected at the respective chromosomal position (for the N20 antibody, data were taken from Fig. 6C). Note that cells infected with the AdTTflag-p32 virus were also coinfected with an equal amount (5 FFU per cell) of the activator virus AdCMVrtTA. The coinfection protocol is necessary in order to provide the reverse tetracycline activator protein that drives Flag-p32 expression (34).

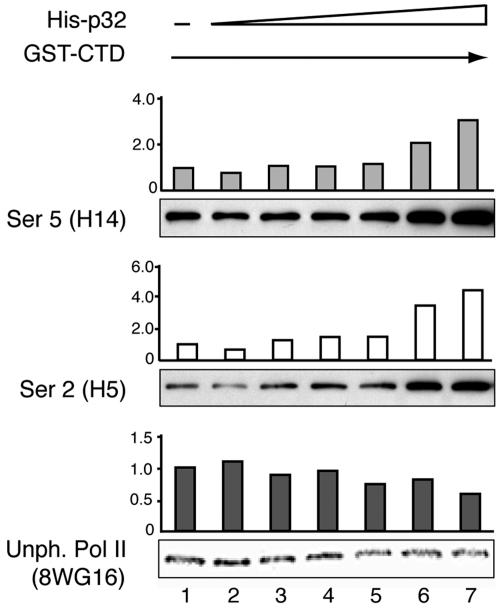

Recombinant His-p32 stimulates CTD phosphorylation in vitro.

To confirm that p32 has the capacity to modulate CTD phosphorylation, we set up an in vitro kinase assay which measured the effect of a bacterially produced His-p32 protein on Ser 2 and Ser 5 phosphorylation of a bacterially produced GST-CTD protein. In this experiment increasing amounts of His-p32 were first preincubated with nuclear extracts prepared from HeLa cells and then further incubated with the GST-CTD substrate. The effect on CTD phosphorylation was measured by Western blot analysis using antibodies that discriminate between different phosphorylated forms of CTD.

As shown in Fig. 8, addition of increasing amounts of recombinant His-p32 caused an increase in both Ser 2 and Ser 5 phosphorylation. At the highest concentration p32 induced a three- to fourfold increase in CTD phosphorylation, with a slightly greater effect on Ser 2 phosphorylation. In contrast, probing the filter with antibody 8WG16 showed a reduction in the signal as the concentration of p32 was increased. This result is expected if 8WG16 under these experimental conditions recognizes only unphosphorylated CTD. It should be noted that we had to use an approximately 200-fold excess of His-p32 in order to see an effect on CTD phosphorylation in vitro. The conditions are, of course, very unphysiological. Despite this caveat we believe that the results may be significant for two reasons. First, we do not know how large a percentage of the recombinant His-p32 or GST-CTD proteins have adopted their native conformations and therefore would be biologically active. Second, the fact that addition of a large excess of a protein activates an enzymatic activity rather than causing an inhibition of activity may be seen as a positive sign for a specific function of that protein.

FIG. 8.

p32 stimulates CTD phosphorylation in vitro. Increasing amounts of a bacterially expressed His-p32 protein (0, 30, 100, 300, 600, 1,200, and 2,400 pmol) were preincubated in HeLa nuclear extracts and then further incubated with a constant amount of GST-CTD (10 pmol). Proteins were separated on an SDS-PAGE gel, and the extent of CTD phosphorylation was quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis of Western blots probed with phosphoepitope-specific antibodies.

Collectively, our results suggest that p32 is able to modulate enzymatic activities in nuclear extract that causes both Ser 2 and Ser 5 phosphorylation. Thus, the results presented are compatible with the hypothesis that p32 stimulates CTD phosphorylation. However, it should be noted that the result does not exclude the possibility that p32 might achieve the same result by inhibiting CTD dephosphorylation. Our future work will address the mechanistic details of how p32 regulates the reversible phosphorylation of CTD.

The endogenous Pol II is hyperphosphorylated in p32-overexpressing cells.

In cells in the late stage of adenovirus infection a large fraction of Pol II is expected to be engaged in transcription from the adenovirus MLTU. In fact, transcription from the MLP accounts for approximately 30% of total RNA synthesis at late times of infection (24). As shown above such polymerases appear to be hyperphosphorylated in cells overexpressing the p32 protein. To analyze the effect of p32 on the endogenous pool of Pol II, we also performed Western blot assays on mini-nuclear extracts prepared from mock- or AdTTflag-p32-infected 293 cells. As shown in Fig. 9A, the basal expression of p32 was low but detectable in uninduced cells (lane 2). However, addition of doxycycline resulted in a dramatic increase in Flag-p32 expression (lane 3).

Probing the filter with the N20 antibody displayed two distinguishable forms of Pol II, the hypophosphorylated IIA and the hyperphosphorylated IIO (Fig. 9B, lane 1). The leakage of p32 expression (Fig. 9A, lane 2) was sufficient to cause a detectable increase in the fraction of Pol IIO (Fig. 9B, lane 2), and induction of p32 expression resulted in a further dramatic rise in the Pol IIO/Pol IIA ratio (Fig. 9B, lane 3). Taken together these results support our conclusion that p32 overexpression results in an increase in Pol II phosphorylation. It is interesting that not only is the ratio between IIO and IIA changed in p32-overproducing cells but also the total signal is increased (Fig. 9B, compare lanes 1 and 3). This result has been observed in multiple experiments and appears to be specific since we have not observed this great increase in Pol II accumulation during a wild-type-adenovirus infection (data not shown). Since N20 recognizes the amino terminus of the Pol II large subunit, the increase in signal intensity most likely results from a phosphorylation-dependent stabilization of Pol II in p32-overexpressing cells.

After stripping, the same filter was reprobed with the H5 or H14 antibody detecting Ser 2- or Ser 5-phosphorylated Pol IIO, respectively. As shown in Fig. 9C and D, p32 overexpression boosted the accumulation of both Ser 2- and Ser 5-phosphorylated Pol IIO. In the uninduced samples (lane 2), Ser 2 and Ser 5 phosphorylation was slightly increased compared to mock-infected cells, whereas the increase in accumulation of Pol IIO was dramatically higher under conditions where p32 was overexpressed (lane 3).

DISCUSSION

The results presented here suggest that overexpression of the cellular p32 protein during an adenovirus infection results in hyperphosphorylation of the CTD on Pol II. Further, the efficiency of Pol II elongation on the MLTU was reduced approximately twofold, and this resulted in a drastic reduction of mRNA and protein accumulation from the MLTU (Fig. 2B and 3B).

Importantly, our analysis shows that virus multiplication, assayed as the efficiency of viral DNA replication, under our experimental conditions is only slightly affected by p32 overexpression. Thus, p32 overexpression causes only a slight delay in viral DNA accumulation, with approximately 60% efficiency at 22 hpi (Fig. 3E). Since only approximately 5% of the viral DNA is being actively transcribed at late times of infection (48), this modest decrease in viral DNA accumulation does not seem to be sufficient to explain the drastic effects we see on mRNA and protein expression from the MLTU (Fig. 2B and 3B).

It is noteworthy that, in wild-type-infected cells, approximately 50% of the Pol II detectable at the MLP is prematurely terminating transcription (Fig. 5B, bars 1 to 3). This block in transcription elongation was expected and has been observed in multiple previous studies (20, 26, 41). A block to effective Pol II elongation has also been observed in other eukaryotic genes, like the dihydrofolate reductase and γ-actin genes, both which show an approximately eightfold enrichment of Pol II at their promoter sites (7). A curious observation was that p32 overexpression resulted in a further twofold reduction in the density of Pol II elongation on the MLTU (Fig. 6C, bars 1 to 3). Thus, in p32-overexpressing cells only 25% of the Pol II that was detected at the MLP made it to the end of the L1 unit (Fig. 6A, lanes 4 to 6). Although the change in Pol II density is relatively small in these experiments, the results are based on six independent experiments and the change has been shown to be statistically significant (see legend to Fig. 6).

The reduction in Pol II elongation was accompanied by a hyperphosphorylation of the CTD. Thus, the fraction of Pol II that continues to the end of the L1 unit was Ser 5 and, to a lesser extent, also Ser 2 hyperphosphorylated. Already the Pol II detected at the promoter showed a twofold increase in Ser 5 phosphorylation (Fig. 7C, bar 1). This overphosphorylation increased to an estimated 4.5-fold-elevated Ser 5 phosphorylation for the fraction of Pol II that reached the end of the L1 unit (Fig. 7C, bar 3). Similarly, p32 overexpression resulted in an approximately twofold increase in Ser 2 phosphorylation (Fig. 7C, bar 6).

From this point it is interesting that the cyclic phosphorylation of CTD is thought to be important for the coupling of transcription and RNA processing (reviewed in references 11 and 29). Thus, CTD is believed to act as a platform recruiting factors needed for capping, splicing, and polyadenylation to the elongating Pol II. Our observation that the Pol II that makes it to the end of the L1 unit is both Ser 5 and Ser 2 hyperphosphorylated suggests that these polymerases do not produce functional mRNA because they fail to recruit the necessary factors needed for correct splicing and/or polyadenylation of the nascent transcript. Such a hypothesis would provide an explanation for the observation that the reduction of mRNA and protein expression from the MLTU (Fig. 2 and 3) was much more severe compared to the twofold-inhibitory effect of p32 on Pol II elongation (Fig. 6C, bars 1 to 3).

Our results also suggest that p32-induced inhibition of MLTU transcription may be dependent on the of binding of the transcriptional activator CBF/NF-Y to the CAAT box in the MLP (Fig. 4A). However, it should be noted that the connection between p32 inhibition of MLP transcription and the effect of p32 on CTD phosphorylation has been observed using completely different experimental systems, i.e., transient transfection and virus infection, respectively. Thus, an AdTTflag-p32 virus with the CAAT box mutated needs to be constructed and tested. However, our model is at least in line with the recent finding that p32 and CBF/NF-Y interacts both in vitro and in vivo and that p32 inhibits α2(1) collagen gene transcription by being recruited to the α2(1) collagen gene promoter (6). Further, our transient-transfection assays using the human tripeptidyl-peptidase II promoter, with or without CAAT boxes, appear to confirm that p32 needs CBF/NF-Y binding sites in the promoter to be able to repress transcription (Fig. 4C).

A key question that remains to be answered is how p32 induces CTD hyperphosphorylation. Here we show that addition of a recombinant p32 protein to nuclear extracts stimulates both Ser 5 and Ser 2 phosphorylation (Fig. 8). This finding is in agreement with our observation that p32 induces both Ser 2 and Ser 5 hyperphosphorylation of the endogenous pool of Pol II (Fig. 9). Our preliminary experiments indicate that p32 does not block CTD dephosphorylation in an in vitro assay system. It will be an interesting future development of the project to address more rigorously whether p32 regulates CTD phosphorylation or CTD dephosphorylation. There are several interesting CTD kinases and CTD phosphatases that might be targets of p32. The most obvious candidates to be analyzed are the CTD kinases CDK7/TFIIH and CDK9/P-TEFb and the CTD phosphatases FCP1 and SCP, although many alternative enzymes might be involved (see also below).

So far we have no evidence that p32 becomes stably associated with the elongating Pol II. Thus, we cannot detect p32 on the MLTU using the Flag epitope antibody in the ChIP assay (data not shown). There are, of course, many simple technical difficulties that could explain the failure to detect p32 associated with Pol II. In an attempt to combine our data into a preliminary model we speculate that p32 may act at an early step in the transcription process. Perhaps, p32 becomes recruited to the MLP via an interaction with CBF/NF-Y. From this promoter-proximal position p32 stimulates either general CTD phosphorylation or alternatively novel Ser 5 and/or Ser 2 residues in the CTD. It should be noted that not all 52 heptapeptide repeats in the CTD are simultaneously phosphorylated. Thus, phosphorylation of CTD at novel sites may generate phosphoepitopes that are not easily dephosphorylated and therefore remain on the elongating Pol II even after that the contact with p32 has been broken. An alternative model is that p32 prevents recruitment of FCP1 to Pol II at the transition state from initiation to elongation. Such an effect might have dramatic effects on both transcription elongation and CTD phosphorylation. Thus, it has been shown that FCP1 has a stimulatory effect on transcription elongation and that this activity is independent of its phosphatase activity (9, 28). Potentially, overexpression of p32 may sequester FCP1, which results in a reduced efficiency of Pol II elongation. Since FCP1 is a candidate phosphatase recycling Pol II at the end of the transcription cycle, a failure to recruit it to the transcribing Pol II might be predicted also to result in a significant hyperphosphorylation of the CTD.

Interestingly, overexpression of the peptidyl-prolyl isomerase Pin 1 resembles in several aspects the effect we observe in cells overexpressing p32. Thus, Pin 1 triggers Ser 5 hyperphosphorylation, stimulates Ser 2 phosphorylation, and also inhibits Pol II transcription in vivo (49). Further, the recombinant Pin 1 protein induces CTD hyperphosphorylation both by inhibiting the CTD phosphatase FCP1 and by stimulating kinase cdc2/cyclin B. Similarly, in HIV-1 Tat-activated transcription Tat inhibits the dephosphorylating activity of FCP1 (30) and stimulates cdk9/P-TEFb to phosphorylate both Ser 2 and Ser 5 (53). Collectively, these results demonstrate that a protein can have a phosphatase-inhibitory function as well as a kinase-stimulatory activity, a result which appears also to be true for the cellular p32 protein.

There is clearly much more to learn about the function(s) of p32 in transcription and splicing in adenovirus-infected cells. This study shed some light on its function by showing that p32 has a capacity to repress mRNA expression from the MLTU and cause CTD hyperphosphorylation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Tanel Punga for much help in setting up the ChIP assay. We also thank Anders Sundqvist, Catharina Svensson, and Anne-Christine Ström for generously providing us with unpublished plasmids. Further, we thank Ann-Christin Lindås and Birgitta Tomkinson for generously providing us with tripeptidyl-peptidase II promoter plasmids.

This work was made possible by a generous grant from the Swedish Cancer Society.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott, K. L., J. Archambault, H. Xiao, B. D. Nguyen, R. G. Roeder, J. Greenblatt, J. G. Omichinski, and P. Legault. 2005. Interactions of the HIV-1 Tat and RAP74 proteins with the RNA polymerase II CTD phosphatase FCP1. Biochemistry 44:2716-2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn, S. H., M. Kim, and S. Buratowski. 2004. Phosphorylation of serine 2 within the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain couples transcription and 3′ end processing. Mol. Cell 13:67-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1995. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 4.Berenjian, S., and G. Akusjärvi. 2006. Binary AdEasy vector systems designed for Tet-ON or Tet-OFF regulated control of transgene expression. Virus Res. 115:116-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers, R. S., B. Q. Wang, Z. F. Burton, and M. E. Dahmus. 1995. The activity of COOH-terminal domain phosphatase is regulated by a docking site on RNA polymerase II and by the general transcription factors IIF and IIB. J. Biol. Chem. 270:14962-14969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chattopadhyay, C., D. Hawke, R. Kobayashi, and S. N. Maity. 2004. Human p32, interacts with B subunit of the CCAAT-binding factor, CBF/NF-Y, and inhibits CBF-mediated transcription activation in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:3632-3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng, C., and P. A. Sharp. 2003. RNA polymerase II accumulation in the promoter-proximal region of the dihydrofolate reductase and γ-actin genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:1961-1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho, E. J., M. S. Kobor, M. Kim, J. Greenblatt, and S. Buratowski. 2001. Opposing effects of Ctk1 kinase and Fcp1 phosphatase at Ser 2 of the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain. Genes Dev. 15:3319-3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho, H., T. K. Kim, H. Mancebo, W. S. Lane, O. Flores, and D. Reinberg. 1999. A protein phosphatase functions to recycle RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 13:1540-1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edholm, D., M. Molin, E. Bajak, and G. Akusjärvi. 2001. Adenovirus vector designed for expression of toxic proteins. J. Virol. 75:9579-9584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstrohm, A. C., A. L. Greenleaf, and M. A. Garcia-Blanco. 2001. Co-transcriptional splicing of pre-messenger RNAs: considerations for the mechanism of alternative splicing. Gene 277:31-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham, F. L., J. Smiley, W. C. Russell, and R. Nairn. 1977. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. J. Gen. Virol. 36:59-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall, K. T., M. S. Giles, M. A. Calderwood, D. J. Goodwin, D. A. Matthews, and A. Whitehouse. 2002. The herpesvirus saimiri open reading frame 73 gene product interacts with the cellular protein p32. J. Virol. 76:11612-11622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirt, B. 1967. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cell cultures. J. Mol. Biol. 26:365-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imperiale, M., G. Akusjärvi, and K. Leppard. 1995. Post-transcriptional control of adenovirus gene expression. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 199:139-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim, Y. K., C. F. Bourgeois, C. Isel, M. J. Churcher, and J. Karn. 2002. Phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain by CDK9 is directly responsible for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat-activated transcriptional elongation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:4622-4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobor, M. S., L. D. Simon, J. Omichinski, G. Zhong, J. Archambault, and J. Greenblatt. 2000. A motif shared by TFIIF and TFIIB mediates their interaction with the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain phosphatase Fcp1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:7438-7449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komarnitsky, P., E. J. Cho, and S. Buratowski. 2000. Different phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II and associated mRNA processing factors during transcription. Genes Dev. 14:2452-2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krainer, A. R., G. C. Conway, and D. Kozak. 1990. Purification and characterization of pre-mRNA splicing factor SF2 from HeLa cells. Genes Dev. 4:1158-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsson, S., C. Svensson, and G. Akusjärvi. 1992. Control of adenovirus major late gene expression at multiple levels. J. Mol. Biol. 225:287-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee, K. A., A. Bindereif, and M. R. Green. 1988. A small-scale procedure for preparation of nuclear extracts that support efficient transcription and pre-mRNA splicing. Gene Anal. Tech. 5:22-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang, X., Y. C. Shin, R. E. Means, and J. U. Jung. 2004. Inhibition of interferon-mediated antiviral activity by murine gammaherpesvirus 68 latency-associated M2 protein. J. Virol. 78:12416-12427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindås, A. C., and B. Tomkinson. 2005. Identification and characterization of the promoter for the gene encoding human tripeptidyl-peptidase II. Gene 345:249-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lucas, J. J., and H. S. Ginsberg. 1971. Synthesis of virus-specific ribonucleic acid in KB cells infected with type 2 adenovirus. J. Virol. 8:203-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo, Y., H. Yu, and B. M. Peterlin. 1994. Cellular protein modulates effects of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev. J. Virol. 68:3850-3856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maderious, A., and S. Chen-Kiang. 1984. Pausing and premature termination of human RNA polymerase II during transcription of adenovirus in vivo and in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:5931-5935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maity, S. N., P. T. Golumbek, G. Karsenty, and B. de Crombrugghe. 1988. Selective activation of transcription by a novel CCAAT binding factor. Science 241:582-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mandal, S. S., H. Cho, S. Kim, K. Cabane, and D. Reinberg. 2002. FCP1, a phosphatase specific for the heptapeptide repeat of the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II, stimulates transcription elongation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:7543-7552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maniatis, T., and R. Reed. 2002. An extensive network of coupling among gene expression machines. Nature 416:499-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall, N. F., G. K. Dahmus, and M. E. Dahmus. 1998. Regulation of carboxyl-terminal domain phosphatase by HIV-1 tat protein. J. Biol. Chem. 273:31726-31730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthews, D. A., and W. C. Russell. 1998. Adenovirus core protein V interacts with p32-a protein which is associated with both the mitochondria and the nucleus. J. Gen. Virol. 79:1677-1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moisan, A., C. Larochelle, B. Guillemette, and L. Gaudreau. 2004. BRCA1 can modulate RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain phosphorylation levels. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:6947-6956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molin, M., L. Bouakaz, S. Berenjian, and G. Akusjärvi. 2002. Unscheduled expression of capsid protein IIIa results in defects in adenovirus major late mRNA and protein expression. Virus Res. 83:197-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molin, M., M. C. Shoshan, K. Ohman-Forslund, S. Linder, and G. Akusjärvi. 1998. Two novel adenovirus vector systems permitting regulated protein expression in gene transfer experiments. J. Virol. 72:8358-8361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mühlemann, O., and G. Akusjärvi. 1998. Preparation of splicing-competent nuclear extracts from adenovirus-infected cells, p. 203-216. In W. S. M. Wold (ed.), Methods in molecular medicine, vol. 21. Humana Press Inc., Totowa, N.J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ni, Z., B. E. Schwartz, J. Werner, J. R. Suarez, and J. T. Lis. 2004. Coordination of transcription, RNA processing, and surveillance by P-TEFb kinase on heat shock genes. Mol. Cell 13:55-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Brien, T., S. Hardin, A. Greenleaf, and J. T. Lis. 1994. Phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain and transcriptional elongation. Nature 370:75-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palancade, B., and O. Bensaude. 2003. Investigating RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain (CTD) phosphorylation. Eur. J. Biochem. 270:3859-3870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petersen-Mahrt, S. K., C. Estmer, C. Öhrmalm, D. A. Matthews, W. C. Russell, and G. Akusjärvi. 1999. The splicing factor-associated protein, p32, regulates RNA splicing by inhibiting ASF/SF2 RNA binding and phosphorylation. EMBO J. 18:1014-1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prage, L., U. Pettersson, S. Höglund, K. Londberg-Holm, and L. Philipson. 1968. Structural proteins of adenoviruses IV. Sequential degradation of the adenovirus type 2 virion. Virology 42:341-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Resnekov, O., E. Ben-Asher, E. Bengal, M. Choder, N. Hay, M. Kessler, N. Ragimov, M. Seiberg, H. Skolnik-David, and Y. Aloni. 1988. Transcription termination in animal viruses and cells. Gene 72:91-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schroeder, S. C., B. Schwer, S. Shuman, and D. Bentley. 2000. Dynamic association of capping enzymes with transcribing RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 14:2435-2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song, B., and C. S. Young. 1998. Functional analysis of the CAAT box in the major late promoter of the subgroup C human adenoviruses. J. Virol. 72:3213-3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stow, N. D. 1981. Cloning of a DNA fragment from the left-hand terminus of the adenovirus type 2 genome and its use in site-directed mutagenesis. J. Virol. 37:171-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas, G. P., and M. B. Mathews. 1980. DNA replication and the early to late transition in adenovirus infection. Cell 22:523-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Scoy, S., I. Watakabe, A. R. Krainer, and J. Hearing. 2000. Human p32: a coactivator for Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen-1-mediated transcriptional activation and possible role in viral latent cycle DNA replication. Virology 275:145-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Virtanen, A., P. Gilardi, A. Näslund, J. M. LeMoullec, U. Pettersson, and M. Perricaudet. 1984. mRNAs from human adenovirus 2 early region 4. J. Virol. 51:822-831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolgemuth, D. J., and M. T. Hsu. 1981. Visualization of nascent RNA transcripts and simultaneous transcription and replication in viral nucleoprotein complexes from adenovirus 2-infected HeLa cells. J. Mol. Biol. 147:247-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu, Y. X., Y. Hirose, X. Z. Zhou, K. P. Lu, and J. L. Manley. 2003. Pin1 modulates the structure and function of human RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 17:2765-2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yeo, M., P. S. Lin, M. E. Dahmus, and G. N. Gill. 2003. A novel RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain phosphatase that preferentially dephosphorylates serine 5. J. Biol. Chem. 278:26078-26085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu, L., P. M. Loewenstein, Z. Zhang, and M. Green. 1995. In vitro interaction of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat transactivator and the general transcription factor TFIIB with the cellular protein TAP. J. Virol. 69:3017-3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zheng, Y. H., H. F. Yu, and B. M. Peterlin. 2003. Human p32 protein relieves a posttranscriptional block to HIV replication in murine cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:611-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou, M., M. A. Halanski, M. F. Radonovich, F. Kashanchi, J. Peng, D. H. Price, and J. N. Brady. 2000. Tat modifies the activity of CDK9 to phosphorylate serine 5 of the RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:5077-5086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]