Abstract

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) BMRF1 protein is a DNA polymerase processivity factor. We have deleted the BMRF1 open reading frame from the EBV genome and assessed the ΔBMRF1 EBV phenotype. ΔBMRF1 viruses were replication deficient, but the wild-type phenotype could be restored by BMRF1 trans-complementation. The replication-deficient phenotype included impaired lytic DNA replication and late protein expression. ΔBMRF1 and wild-type viruses were undistinguishable in terms of their ability to transform primary B cells. Our results provide genetic evidence that BMRF1 is essential for lytic replication of the EBV genome.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a human herpesvirus that infects most individuals and can cause an infectious mononucleosis syndrome when infecting adolescents. EBV is etiologically associated with numerous malignancies, including endemic Burkitt's lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and certain forms of B-cell lymphoma (for a review, see reference 6). EBV can infect its target cells in both a latent and a lytic mode. The minimal set of proteins necessary for replication of EBV oriLyt includes the DNA polymerase BALF5, the single-stranded DNA-binding protein BALF2, the primase BSLF1, the helicase BBLF4, a component of the helicase-primase complex BBLF2/3, and the DNA polymerase processivity factor BMRF1 (also called diffuse early antigen [EA-D]) (7, 14, 21, 22). The contribution of these proteins to lytic replication in the context of the whole virus in which a large number of viral proteins interact together in a finely tuned way has, however, not been assessed yet. BMRF1 is an early gene (1) whose transcription is activated by the BZLF1 lytic transactivator (13). The BMRF1 protein is recruited to replication compartments within the nuclei of lytically replicating cells (2). BMRF1 enhances expression of the viral early gene BHLF1 (25) and of the cellular gastrin gene (10).

DNA polymerase processivity factors form a heterogeneous group of proteins, most of which function as “sliding clamps” (19, 20). In contrast to these sliding clamps, the herpes simplex virus (HSV) processivity factor, UL42, directly binds DNA with high affinity (23). A UL42 HSV knockout genome was found to produce no infectious progeny, viral DNA, or late gene products (12), corroborating earlier results about DNA synthesis from an HSV origin (24). Even if related, lytic replication in EBV and that in HSV also show some profound differences. These include preferential establishment of latency in B lymphocytes, EBV's natural cellular host, and a comparatively low permissivity for EBV lytic replication in infected cells. At the molecular level, ClustalW alignment shows a low degree of homology (17% identity) between BMRF1 and UL42. Altogether, it is not possible to draw conclusions about BMRF1 functions from what is known about UL42. Here we report the phenotype of an EBV mutant carrying a complete deletion of the BMRF1 open reading frame.

Construction of the ΔBMRF1 EBV genome.

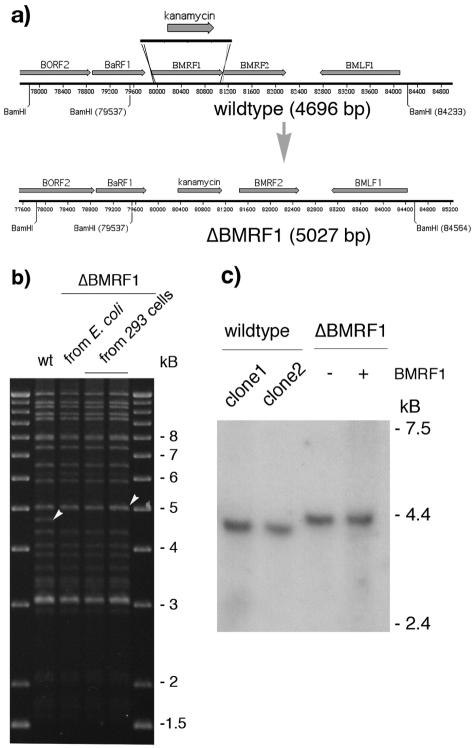

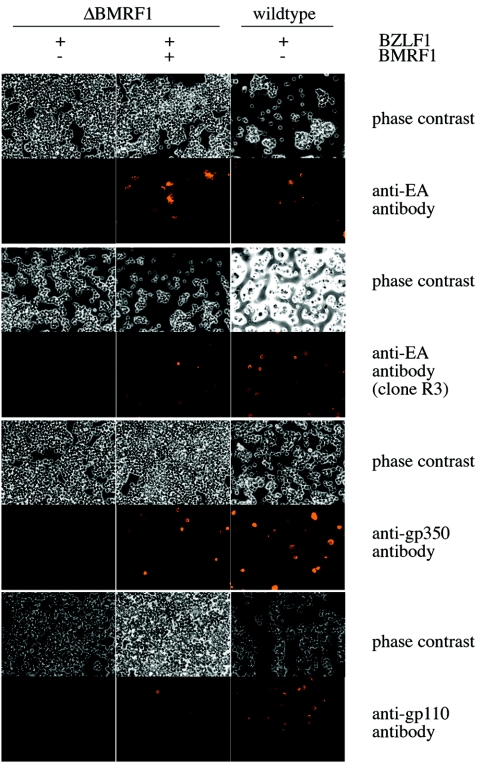

We exchanged the entire BMRF1 open reading frame for the kanamycin resistance gene using the strategy depicted in Fig. 1. This technique is based on homologous recombination between a targeting vector and the entire B95.8 EBV genome cloned as a plasmid in the Escherichia coli strain DH10B (3, 16). The cloned EBV carries a hygromycin resistance gene as well as a gene encoding a green fluorescent protein (Clontech). The construct resulting from this recombination, ΔBMRF1, was stably transfected into 293 cells (9) that were previously shown to be permissive for EBV replication (4). Outgrowing hygromycin-resistant 293 clones carrying the mutant EBV (293/ΔBMRF1) were tested for their suitability to evaluate the ΔBMRF1 phenotype. We first assessed the structure of the mutant viral DNA present in E. coli cells and in 293 cells by restriction analysis using several restriction enzymes (Fig. 1a and b). This analysis confirmed that these cells carried a viral genome that was structurally intact but devoid of the ΔBMRF1 gene. Because BaRF1 and BMRF1 are translated from the same RNA, it was important to exclude the possibility that insertion of the BMRF1 targeting vector could have altered BaRF1 transcription (15). We therefore performed a Northern blot analysis on induced 293/ΔBMRF1 and 293/wt-EBV with a BaRF1-specific probe. This analysis showed no difference between the two cell lines (Fig. 1c). In a further step, we induced lytic replication by transfection of the transactivator BZLF1 into 293/ΔBMRF1 cells (Fig. 2). Staining of the induced 293/ΔBMRF1 cells with two antibodies specific for BMRF1 (Chemicon) (17) was negative, confirming the mutant status of this EBV genome (Fig. 2). We then complemented the ΔBMRF1 mutant by cotransfection of the BZLF1 and BMRF1 (26) genes into different 293/ΔBMRF1 clones. Incubation of supernatants from these clones with Raji cells (a human Burkitt's lymphoma cell line) (18) resulted in infection as demonstrated by the observation of green fluorescent protein-positive Raji cells (data not shown). This assay showed that the complemented 293/ΔBMRF1 is fully able to replicate and is therefore suitable for the study of the ΔBMRF1 phenotype. It also allowed selection of the best 293/ΔBMRF1 virus producer cell line, with which subsequent experiments were performed.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the strategy used to construct a ΔBMRF1 EBV. (a) To disrupt the BMRF1 gene, the kanamycin resistance gene was amplified by PCR from pCP15 using primers that introduce 40-bp stretches of homology to sequences immediately upstream and downstream of the BMRF1 gene (EBV coordinates 79859 to 79899 and 81111 to 81150, respectively). Recombination of this linear DNA fragment with the wild-type EBV genome in E. coli leads to an exchange between the kanamycin cassette and the BMRF1 gene region, leading to an increase in size of the BamHI-M fragment from 4,696 bp to 5,027 bp. (b) Restriction analysis of the ΔBMRF1 mutant. Following recombination, the integrity of the recombinant ΔBMRF1 genome was analyzed at different steps of the mutant's construction. The mutant DNA was subjected to restriction analysis both before its transfer to the EBV-permissive 293 cell line and after its rescue from one of the obtained 293/ΔBMRF1 clones into E. coli cells. The restriction pattern obtained was compared to the one obtained after digestion of the wt EBV genome. Except for the wt 4,696-bp fragment that is exchanged for a 5,027-bp fragment in ΔBMRF1 (see white arrowheads), the overall structure of the mutant appears unchanged. This confirms the integrity and the mutant character of the 293/ΔBMRF1 cells. (c) Northern blot analysis of the transcription of the upstream BaRF1 gene of BMRF1. RNA from lytically induced cells was electrophoresed on a formaldehyde-1.2% agarose gel, blotted onto a Hybond N+ membrane, and hybridized with a radioactively labeled probe specific for the EBV BaRF1 gene. The intensities of the bands from two wild-type (B95.8) and noncomplemented or complemented ΔBMRF1 clones are very similar, proving that there is no effect of the BMRF1 deletion on the expression of the BaRF1 gene. The transcript in the ΔBMRF1 mutant is 330 bp longer since it spans the site of insertion of the kanamycin resistance gene.

FIG. 2.

ΔBMRF1 cells produce neither the BMRF1 protein nor lytic cycle late proteins. 293/ΔBMRF1 and 293/wt-EBV cells were transfected with an expression plasmid for the BZLF1 gene to induce the lytic cycle and stained with antibodies directed against the BMRF1 protein (the EA-D early antigen). Lytically induced 293/ΔBMRF1 cells do not produce the antigen, whereas mutant cells complemented with BMRF1 and wild-type cells do, confirming that the ΔBMRF1 genome lacks the BMRF1 gene. When the same cells were stained with antibodies directed against the gp350 or gp110 late antigen, 293/ΔBMRF1 cells were found to produce neither gp110 nor gp350. In contrast both complemented 293/ΔBMRF1 cells and wild-type cells stained positive for these antigens.

BMRF1 is essential for lytic protein synthesis and lytic DNA replication.

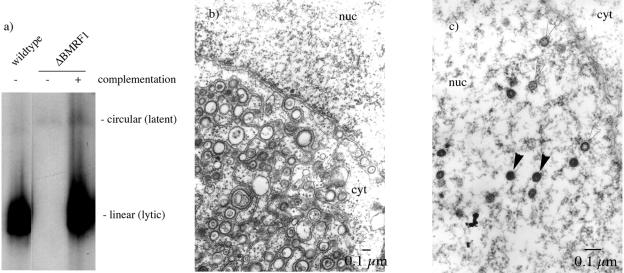

We then performed immunostaining on lytically induced 293/ΔBMRF1 cells with antibodies directed against the gp110 and gp350 EBV late proteins that proved to be negative (Fig. 2). In contrast, both proteins could be readily detected both in induced cells carrying wild-type (wt) EBV (293/wt-EBV) and in BMRF1-complemented 293/ΔBMRF1 cells. The ability of ΔBMRF1 to replicate was assessed by Southern blotting with an EBV-specific probe (BamHI-W repeats) (Fig. 3a). Induced 293/ΔBMRF1 cells were lysed in the slots of an agarose gel and electrophoresed to separate the linear and circular forms of the EBV genome (5, 8). BMRF1-complemented 293/ΔBMRF1 cells and 293/wt-EBV cells were included as controls. Linear EBV genomes that result from lytic replication could be detected in BMRF1-complemented 293/ΔBMRF1 cells and 293/wt-EBV cells but not in induced 293/ΔBMRF1 cells. These results were confirmed by direct observation of induced cells with electron microscopy. No mature or immature viral structures were visible in more than 100 induced 293/ΔBMRF1 cells (Fig. 3b). In contrast, mature and immature virions were readily detected in the nucleus of BMRF1-complemented 293/ΔBMRF1 cells (Fig. 3c). All together, these results provide solid evidence that BMRF1 is absolutely required for both DNA lytic replication and lytic protein synthesis.

FIG. 3.

ΔBMRF1 cells do not lytically replicate. (a) ΔBMRF1 viral lytic DNA replication cannot be detected in Gardella gel electrophoresis. DNA from lytically induced cells was electrophoresed on an 0.8% agarose gel, blotted onto a Hybond N+ membrane, and hybridized with a radioactively labeled probe specific for the EBV BamHI-W repeats of EBV. The mutant EBV genome DNA is not replicated. In contrast, strong signals from linear EBV genomes were detected in the 293/wt-EBV and in the 293/ΔBMRF1 cells complemented with a BMRF1 expression plasmid. (b and c) Lytically induced 293/ΔBMRF1 cells do not produce EBV virions. 293/ΔBMRF1 cells were lytically induced and fixed in glutaraldehyde. Ultrathin sections were analyzed by electron microscopy (b). The same experiment was performed in parallel with 293/ΔBMRF1 cells cotransfected with an expression plasmid carrying the BMRF1 gene (c). In the 293/ΔBMRF1 cells no viral nucleocapsids could be observed. In contrast, these were readily visible in 293/ΔBMRF1 cells complemented with BMRF1. Arrowheads point to empty capsids (open arrowheads) or capsids filled with DNA (filled arrowheads). nuc, nucleus; cyt, cytoplasm.

BMRF1 does not contribute to B-cell immortalization.

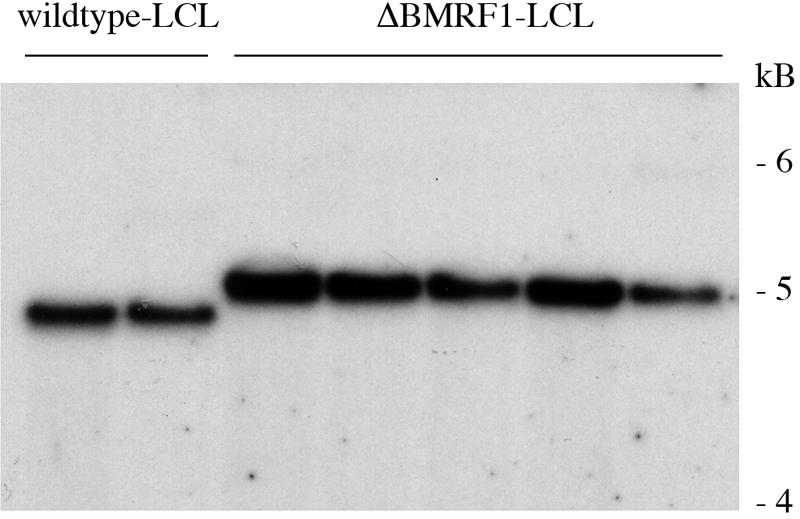

Supernatants containing either BMRF1-complemented ΔBMRF1 or wt EBV virus were incubated with peripheral blood B cells purified with CD19 Dynabeads (Dynal). Infections were performed at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) ranging from 0 to 100 particles per B cell. One thousand infected B cells were plated per well on 96-well cluster plates containing irradiated human fibroblasts. The ability of the viruses to immortalize B cells was evaluated by assessing the proportion of EBNA2-positive cells 3 days after infection and by counting cell outgrowth after 4 weeks. EBNA2 is essential for B-cell transformation, and its expression is a good marker of this process. No significant difference was observed between the two tested viral strains (5% versus 6% EBNA2-positive cells at an MOI of 1, 14% versus 15% at an MOI of 10, and 81% versus 65% at an MOI of 100 after infection with wt EBV and complemented ΔBMRF1, respectively). Cell outgrowth was also very similar (6% versus 8% wells containing immortalized colonies at an MOI of 1, 54% versus 58% at an MOI of 10, and 100% versus 100% at an MOI of 100 after infection with wt EBV and complemented ΔBMRF1, respectively). No outgrowth was observed in uninfected B cells or in cells infected with noncomplemented ΔBMRF1 virus. To confirm that the EBV-immortalized B-cell lines carried the viral strains with which they were infected, we analyzed the structure of the BMRF1 locus by Southern blotting (Fig. 4). As expected, B cells immortalized with ΔBMRF1 carried this viral mutant only. Our results show that BMRF1 is not required for maintenance of B-cell immortalization. Since BMRF1 cannot be detected in the mature virion (11), it is unlikely to play a role in the early stages of immortalization either.

FIG. 4.

Lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL) generated by infection of primary B cells with ΔBMRF1 virus contains the mutant genome only. Genomic DNA extracted from LCL generated by infection of B cells with either wt EBV or complemented ΔBMRF1 virus (ΔBMRF1-LCL) was cleaved with the BamHI restriction enzyme and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, and Southern blotting analysis was performed with a probe for the BMRF2 gene. Blots were hybridized with a BMRF2-specific probe. The BMRF2 gene is located on the BamHI-M fragment of the EBV genome and allows distinction between the wild-type BamHI-M fragment, which is 4.7 kb in size, and the BamHI-M fragment of the ΔBMRF1 mutant, which is 5.0 kb (Fig. 1). This analysis confirms that B cells immortalized with the ΔBMRF1 virus carry the mutant gene while B cells infected with wt EBV carry an intact BamHI-M fragment.

In summary, deletion of the BMRF1 gene from the EBV genome has drastic effects on the virus: viral DNA cannot be replicated any more and the virus is unable to produce late antigens. Thus, the phenotype of this mutation is very similar to the one observed in a UL42 mutant of HSV (12), despite the lack of significant sequence homology between the two proteins. The BMRF1 gene proved to be essential for the production of infectious EBV progeny, which makes its gene product a possible target for antiviral therapy. The ΔBMRF1 EBV would represent a suitable basis for the generation of “one-shot” EBV-based vectors that immortalize B cells but cannot spread. In addition, the EBV ΔBMRF1 provides an essential tool to study the phenotype of BMRF1 mutants.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. Kenney for the BMRF1 expression plasmid and to B. Hub for expert technical assistance with the electron microscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayliss, G. J., and H. Wolf. 1981. The regulated expression of Epstein-Barr virus. III. Proteins specified by EBV during the lytic cycle. J. Gen. Virol. 56:105-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daikoku, T., A. Kudoh, M. Fujita, Y. Sugaya, H. Isomura, N. Shirata, and T. Tsurumi. 2005. Architecture of replication compartments formed during Epstein-Barr virus lytic replication. J. Virol. 79:3409-3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delecluse, H. J., T. Hilsendegen, D. Pich, R. Zeidler, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1998. Propagation and recovery of intact, infectious Epstein-Barr virus from prokaryotic to human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:8245-8250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delecluse, H. J., S. Schuller, and W. Hammerschmidt. 1993. Latent Marek's disease virus can be activated from its chromosomally integrated state in herpesvirus-transformed lymphoma cells. EMBO J. 12:3277-3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fields, B. N., D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, and D. E. Griffin. 2001. Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 7.Fixman, E. D., G. S. Hayward, and S. D. Hayward. 1992. trans-acting requirements for replication of Epstein-Barr virus ori-Lyt. J. Virol. 66:5030-5039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardella, T., P. Medveczky, T. Sairenji, and C. Mulder. 1984. Detection of circular and linear herpesvirus DNA molecules in mammalian cells by gel electrophoresis. J. Virol. 50:248-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham, F. L., J. Smiley, W. C. Russell, and R. Nairn. 1977. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. J. Gen. Virol. 36:59-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holley-Guthrie, E. A., W. T. Seaman, P. Bhende, J. L. Merchant, and S. C. Kenney. 2005. The Epstein-Barr virus protein BMRF1 activates gastrin transcription. J. Virol. 79:745-755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johannsen, E., M. Luftig, M. R. Chase, S. Weicksel, E. Cahir-McFarland, D. Illanes, D. Sarracino, and E. Kieff. 2004. Proteins of purified Epstein-Barr virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:16286-16291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson, P. A., M. G. Best, T. Friedmann, and D. S. Parris. 1991. Isolation of a herpes simplex virus type 1 mutant deleted for the essential UL42 gene and characterization of its null phenotype. J. Virol. 65:700-710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenney, S. C., E. Holley-Guthrie, E. B. Quinlivan, D. Gutsch, Q. Zhang, T. Bender, J. F. Giot, and A. Sergeant. 1992. The cellular oncogene c-myb can interact synergistically with the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 transactivator in lymphoid cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:136-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiehl, A., and D. I. Dorsky. 1991. Cooperation of EBV DNA polymerase and EA-D(BMRF1) in vitro and colocalization in nuclei of infected cells. Virology 184:330-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mellinghoff, I., M. Daibata, R. E. Humphreys, C. Mulder, K. Takada, and T. Sairenji. 1991. Early events in Epstein-Barr virus genome expression after activation: regulation by second messengers of B cell activation. Virology 185:922-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neuhierl, B., and H. J. Delecluse. 2005. Molecular genetics of DNA viruses: recombinant virus technology. Methods Mol. Biol. 292:353-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearson, G. R., B. Vroman, B. Chase, T. Sculley, M. Hummel, and E. Kieff. 1983. Identification of polypeptide components of the Epstein-Barr virus early antigen complex with monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 47:193-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pulvertaft, J. V. 1964. Cytology of Burkitt's tumour (African lymphoma). Lancet 39:238-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stukenberg, P. T., P. S. Studwell-Vaughan, and M. O'Donnell. 1991. Mechanism of the sliding beta-clamp of DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 266:11328-11334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tinker, R. L., G. A. Kassavetis, and E. P. Geiduschek. 1994. Detecting the ability of viral, bacterial and eukaryotic replication proteins to track along DNA. EMBO J. 13:5330-5337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsurumi, T. 1993. Purification and characterization of the DNA-binding activity of the Epstein-Barr virus DNA polymerase accessory protein BMRF1 gene products, as expressed in insect cells by using the baculovirus system. J. Virol. 67:1681-1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsurumi, T., T. Daikoku, R. Kurachi, and Y. Nishiyama. 1993. Functional interaction between Epstein-Barr virus DNA polymerase catalytic subunit and its accessory subunit in vitro. J. Virol. 67:7648-7653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weisshart, K., C. S. Chow, and D. M. Coen. 1999. Herpes simplex virus processivity factor UL42 imparts increased DNA-binding specificity to the viral DNA polymerase and decreased dissociation from primer-template without reducing the elongation rate. J. Virol. 73:55-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu, C. A., N. J. Nelson, D. J. McGeoch, and M. D. Challberg. 1988. Identification of herpes simplex virus type 1 genes required for origin-dependent DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 62:435-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang, Q., E. Holley-Guthrie, J. Q. Ge, D. Dorsky, and S. Kenney. 1997. The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA polymerase accessory protein, BMRF1, activates the essential downstream component of the EBV oriLyt. Virology 230:22-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang, Q., Y. Hong, D. Dorsky, E. Holley-Guthrie, S. Zalani, N. A. Elshiekh, A. Kiehl, T. Le, and S. Kenney. 1996. Functional and physical interactions between the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) proteins BZLF1 and BMRF1: effects on EBV transcription and lytic replication. J. Virol. 70:5131-5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]