The Tudor barber-surgeon, Thomas Vicary (1490?–1561/2) is remembered for three main reasons. As Sergeant-Surgeon to Henry VIII, he used his position at court to advance the status of surgery in England. In the famous Holbein painting, Henry VIII is shown handing the charter of the 1540 Act of Union between the Barbers and Surgeons to Vicary, emphasizing the prominent role he played in promoting this amalgamation. Second, Vicary played a major role in the successful refoundation of one of the great London hospitals, St Bartholomew's, after the dissolution of the monasteries. Third, he was the author of the first textbook of anatomy published in English, which is the subject of this article.1

Vicary was a leading surgeon in London in the mid-sixteenth century, becoming Master of the Barber-Surgeons' Company on four separate occasions. He had risen from obscurity in Kent, where, according to John Manningham, he was “but a meane practiser in Maidstone … that had gayned his knowledge by experience, untill the King advanced him for curing his sore legge”.2 Henry was on a royal progress in Kent, and Vicary was probably called in as the local surgeon. In any event, his services must have been appreciated for within a short time he was promised the post of Sergeant-Surgeon to the King, which he took up in 1535 or 1536.3 In London at that time there were around 100 surgeons in the Barber-Surgeons' Company, out of a total of some 250 physicians, surgeons and apothecaries, and probably an equal number of mostly unlicensed practitioners.4 This was therefore a small world, where the surgeons would all have known each other, as well as most of their other fellow medical professionals.

In 1577, some fifteen years after his death, the surgeons at St Bartholomew's Hospital published a work entitled The anatomie of mans body, which they attributed to Thomas Vicary. In fact, as first shown by J F Payne in 1896, this work was very similar to a manuscript (MS 564) now in the possession of the Wellcome Library (Figure 1).5 This manuscript is a fifteenth century (c.1475) copy of an earlier text written in Middle English around 1392 by an anonymous London surgeon, who copied the work of earlier writers.6 Robert Mory transcribed about a third of Wellcome MS 564, primarily the part describing the anatomy of man, and approached the writing from an analysis of the Middle English used. He placed the work in the context of surgical and medical writing of the time (thirteenth and fourteenth centuries), and demonstrated that the compiler of the tract knew the works of Guido Lanfranc and Henri de Mondeville.7 Regarding the anonymous author, Mory remarked, “It seems certain that he was an Englishman, for his command of English is that of a native”, and the fact “that he was actually practising in London is attested to by the various personal observations throughout the text”.8 He described the prose as “impressive”, adding, “It is characterised by lucidity, vigor, straightforwardness, and as such represents an impressive achievement for its time”.9

Figure 1.

Page 94 of Wellcome MS 564, largely derived from a 1392 translation of work by Henri de Mondeville. It was from this MS, or one very similar, that Vicary compiled his Anatomie. (Courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London.)

It seems likely that Vicary possessed the fourteenth-century treatise, or one very similar, and then produced a shortened version.10 He probably took the view that this material was part of established knowledge, going back to Greek, Roman and Arab sources. There is no evidence that Vicary professed to be the primary author, and he may well have considered he was simply abridging an existing text. Although Vicary followed the Wellcome manuscript closely, his work was not an exact copy, as shown in the following comparison:

[MS 564] I think in this chapter with the grace of God to touch the qualities forms and manners of a surgeon, & it containeth only but one doctrine. In this first doctrine as Lamkfrank [sic] saith, that as thing that we would know, we must know by one of these three manners, or by his name, or by his working, or by his being, showing properties of him self. Then it followeth, that in these same manners we, we [sic] must know surgery, first by his name. As thus, Surgery cometh of Siros, that is a work of greeks. That is in English, An hand. And of Tiros, a work of greeks, that is in english working. For the end and the profit of surgery is of hand working. And as Galen saith, he that would know the soothfastness of a thing, busy him not to know only the name of the thing: but the working and the effect of the same thing, wherefore as avicenne saith, he that would know what surgery is, he must understand that it is a medicinable science, which that, teacheth us to work with hands in mans body In cutting or opening those parts that be whole, And in healing those that are tobroken or cutt right as they were before, or else as nigh as a man may, and also in doing away of that, that is too much above the skin, as wens, warts, or flesh too high. But moreover it is thus expounded, Surgery is the last instrument of medicine …11

This passage may be compared with the equivalent passage from Vicary's 1577 work:

The fyrst is, to know what thing Chirurgerie is. Heerin I doo note the saying of Lamfranke, whereas he sayth, Al things that man would knowe, may be knowen by one of these three things: That is to say, by his name, or by his working, or els by his very being and shewing some of his owne properties. So then it followeth, that in the same manner we may know what Chirurgerie is by three thinges. First, by his name, as thus, The Interpreters write, that Surgerie is derived oute of these wordes, Apto tes Chiros, cai tou ergou, that is too bee vnderstanded, A hand working, and so it may be taken for al handy artes. But noble Ipocras sayth, that Surgerie is hande working in mans body; for the very ende and profite of Chirurgerie is hande working. Nowe the seconde manner of knowing what thing Chirurgerie is, it is the saying of Anicen to be knowen by his beeing, for it is verely a medecinal science: and as Galen sayth, he that wyl knowe the certentie of a thing, let him not busy him selfe to knowe only the name of that thing, but also the working and the effect of the same thing. Nowe the thirde way to knowe what thing Chirurgerie is, It is also to be knowen by his beeing or declaring of his owne properties, the which teacheth vs to worke in mannes body with handes: as thus, In cutting or opening those partes that be whole, and in healing those partes that be broken or cut, and in taking away that that is superfluous, as warts, wennes, skurfulas, and other lyke. But further to declare what Galen sayth Surgery is, it is the laste instrument of medecine …12

There is a tradition, based on two main references, that Vicary's Anatomie was first published in 1548. John Halle briefly mentions Vicary in his prologue to ‘A very frutefull and necessary briefe worke of Anatomie’, which is part of his book A most excellent and learned woorke of chirurgerie, called Chirurgia parva Lanfranci, Lanfranke of Mylayne, published in 1565. Halle, who like Vicary came from Kent, translated into English Lanfranc's work of two centuries earlier, and in the prologue he says he is “somwhat encouraged by the example of good maister Vicarie, late sargeante chyrurgien to the queens highnes: Who was the firste that ever wrote a treatyse of Anatomie in Englyshe, (to the profite of his brethren chirurgiens, and the helpe of younge studentes) as farre as I can learne.”13 Halle does not state the work was published, but simply remarked that Vicary was the first to write a treatise on anatomy in English. The other early reference is by John Aiken, in his Biographical memoirs of medicine in Great Britain, published in 1780.14 He comments:

The title of his work is A Treasure for Englishmen, containing the Anatomie of Man's Body, printed, London, 1548; or, as given by Ames, A profitable Treatise of the Anatomy of Man's Body, compiled by T. Vicary, and published by the Surgeons of St. Bartholomew's Hospital, London, 1577, 12mo. It was likewise published in 1633, in 4to.15

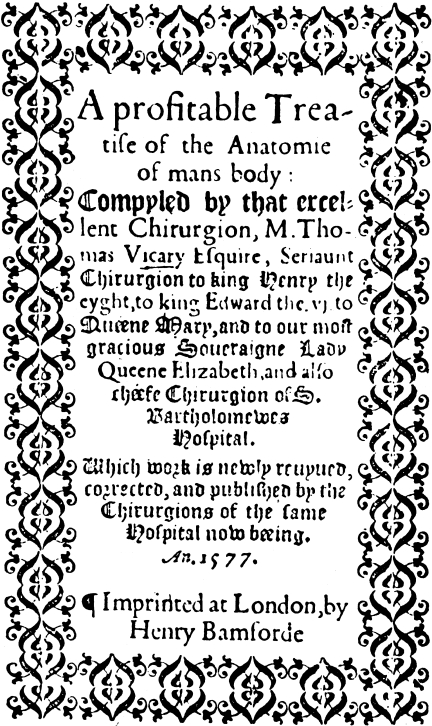

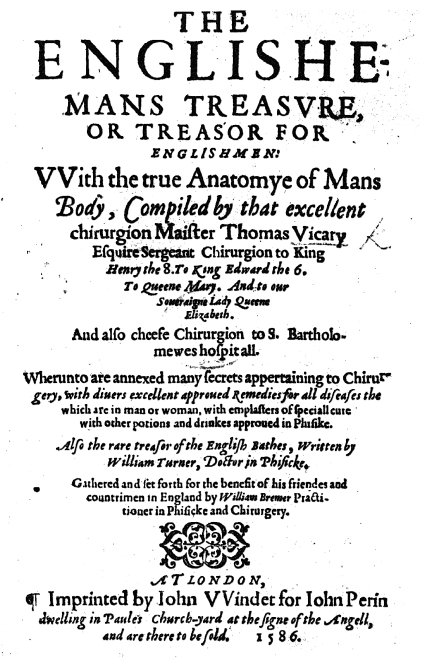

Aikin goes on to describe the work as “a short piece, designed for the use of his more unlearned brethren, and taken almost entirely from Galen and the Arabians”.16 Nevertheless, there are some anomalies in his remarks: he does not mention the publisher or the size of the book, and the second title he cites is that of the edition published by the St Bartholomew's Hospital surgeons in 1577. If there had been an earlier edition, it seems odd that Vicary's former colleagues changed the title from A treasure for Englishmen: containing the true anatomye of mans body (which was the title of the purported 1548 edition) to A profitable treatise of the Anatomie of mans body for the 1577 edition, and then reverted to the original title for the 1586 and later editions. It is more likely that Aikin had never seen a 1548 edition, and the reason the title was changed for the 1586 edition was that two other authors (William Turner and William Bremer) also contributed, and the scope of the work had now changed (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Title-page of the first edition of A profitable treatise of the Anatomie of mans body, London, Henry Bamford, 1577. (Courtesy of the British Library.)

Figure 3.

Title-page of the second edition, London, John Windet for John Perin, 1586. The names of William Turner and William Bremer now appear on the title page. (Courtesy of the British Library.)

It is also noteworthy that the edition of 1613 was called the sixth edition. If there had indeed been a published version of the 1548 work, the 1613 edition should by rights have been the seventh edition. Subsequent editions were called the seventh and eighth, so this was not some simple mistake in 1613. It seems unlikely that less than forty years after the 1577 edition, the publishers were unaware of the existence of a 1548 edition. There is therefore no convincing evidence that the work was printed in Vicary's lifetime, and it was not until 1577 that the surgeons of St Bartholomew's published his work. As Payne suggested, they may have a found a manuscript tract which they regarded as Vicary's, though he had never laid claim to it, and published it as his.17 There is no record in modern times of anybody seeing a 1548 edition, so on balance the most likely explanation is that Vicary produced a manuscript in 1548, and circulated it widely among his professional brethren in London, as was common practice at the time. Some years after his death, his fellow surgeons were moved to publish this manuscript as a small textbook, perhaps because they considered Vicary had not been given credit for his work.

An interesting sidelight on the question of authorship is that another work associated with St Bartholomew's, namely the Ordre of the hospital of S. Bartholomewes, published in 1552, was also largely written by Thomas Vicary, yet his name does not appear on the title page.18 An entry in the Minutes of the Court of Aldermen, for 11 February 1551/2 states the following: “Item. It is agreid that the boke that Thomas Vycars barbour-surgeon hath devysed for the releif of the poor shalbe putt in prnyt and that my lord mayor shall speak to Ric Grafton for the doinge thereof”.19 Richard Grafton duly published the Ordre of the hospital in 1552 but gave no credit to Vicary. Could it have been that four years earlier Vicary had “devysed” and circulated an anatomical manuscript, also without his name on it, and, because others subsequently used this work without acknowledging him, his former colleagues decided after his death to publish it, so as to give credit to the true author?

Vicary used de Mondeville and Lanfranc as his primary sources, via the Wellcome manuscript, and he in turn seems to have been plagiarized. In 1545 Thomas Geminus published his Compendiosa totius anatomica delineatio, which reproduced the plates of Vesalius's Epitome, together with the Latin text.20 This supplied a need, but the fact that it was not in the vernacular prevented its being freely accessible. The situation was remedied when Geminus, encouraged by the sale of his fully illustrated edition of the Epitome, despite its Latin text, was persuaded, perhaps by John Caius, to print an edition in the vernacular.21 An English translation by Nicholas Udall was brought out in 1553, for the benefit of the “unlatined surgeon”, as Geminus called them.22 However, Sanford Larkey found that this was not a simple translation of the Geminus compendium, as had been assumed; in fact some radical changes were made. One of these was the omission of the text of the Epitome, which was substituted by another anatomical treatise entitled ‘Of the partes of mannes bodye’. The wording is almost identical with that of Vicary's 1577 edition. Larkey concluded that both Udall and the 1577 Vicary were probably taken from the lost 1548 Vicary, rather than from the Wellcome manuscript.23

The use of Vicary's text for the 1553 edition of Geminus is not as inexplicable as might at first appear. Udall's problem was to find some text to accompany the Vesalian plates. Such a work, combining the functions of an atlas and a dissecting manual, would have obvious popularity with students. The Vesalian method of presenting the anatomy in systems is not the best way to dissect a body, especially when one remembers how dissections were performed in the sixteenth century. Equally, the classical texts were unsuitable, as in these the anatomy is described from head to feet. Udall realized that the method of Mundinus of Bologna, as exemplified in his Anothomia of 1316, was the answer to the problem. In this method, the abdominal viscera are described first, then the thoracic contents, and lastly, the muscles and bones. There had been compiled, only some five years previously, a “regional” anatomy in English by one of the leading surgeons in the land. Viewed in this light, it is not surprising that Udall took Vicary's manuscript, made some transpositions, and used it for the 1553 Compendium. It was readily adaptable for Udall's purpose, and he was saved the necessity of translating the Epitome and then rearranging it in a form suitable for dissection.24

The book attributed to Vicary outlasted him by almost a hundred years, which is perhaps surprising considering that at the time he was working in London a scientific revolution was taking place with the publication in Basle in 1543 of De humani corporis fabrica by Andreas Vesalius. This monumental book, with large detailed plates of the dissected human body drawn by Jan van Calcar and others from the workshop of Titian, represented the new thinking of the Renaissance.25 Vesalius's approach, based on direct observation and dissection of the human body, eventually replaced the old Galenical teaching on the structure of the body based largely on animal dissection, which had survived for some 1400 years. But Vicary was probably an “unlatined surgeon” and De fabrica was written in Latin, so he stuck to his familiar but obsolete sources, going back to Galen. Vicary wrote in the vernacular, and intended his work for students who were similarly unlatined. Barber-surgeons were not university graduates and, while many of them may have had some knowledge of Latin from their schooldays, it seems likely that students preferred to read textbooks in English. For example, in their dedication to the 1577 edition of the Anatomie, William Clowes and the other surgeons at St Bartholomew's Hospital, write that they had “newly revived, corrected, & published abroad” Vicary's work, although they do “lack the profound knowledge and sugred eloquence of the Latin and Greeke tongues”.26 Similarly, in the will of Robert Balthrop (1591), a bequest was made to the Barber-Surgeons' Company of some his surgical works “written into Englishe for the love that I owe unto my bretheren practisinge Chirurgery and not understandinge the latin Tounge”.27 Although in 1556 the Company ordered that a barber-surgeon could employ only an apprentice who knew Latin and Greek, the following year this rule was set aside so that apprentices did not require to be “lerned in the Latin Tonge”.28 Vicary's work, therefore, was a useful dissecting guide in the vernacular for students of anatomy not proficient in Latin.

The first edition is a small book, and may truly be described as pocket-sized (12mo). Only two copies exist: one in the British Museum, and the other in Cambridge University Library. In the second edition, brought out in 1586, the title of the work changed from A profitable treatise of the Anatomie of mans body to The Englishemans treasure, or treasor for Englishmen: with the true Anatomye of mans body and this title remains through successive editions until the final edition, when it is changed again. The 1586 edition has grown to 115 pages, and only the first 60 pages contain the Anatomie. The remainder of the book is made up as follows: pages 61–101 list the medicines for various complaints, headed ‘Certain Remedies for Captaines and Souldairs that travell either by water, or by Lande’; pages 102–104 contain an account of the urine, headed ‘A breife Treatise of urines’; finally, pages 105–115 give a description ‘Of the Bath of Baeth in englande’. By the second edition, almost half the book has already nothing to do with Vicary and his Anatomie, and the names of William Turner and William Bremer also appear on the title page, remaining there until the final edition. For the third edition, brought out in 1587, there was a change of publisher and the number of pages were reduced slightly to 110, but the book remains substantially the same as the previous edition. There is also a change of publisher for the 1596 edition, but again it is virtually unchanged from the two previous ones, as was the subsequent 1599 edition (see Table 1).

Table 1.

The editions of Vicary's Anatomie of mans body

| Edition | Size | Title | Publishers (all in London) |

|---|---|---|---|

| lst: 1577 | 12mo | A profitable treatise of the Anatomie of mans body | Henry Bamford |

| 2nd: 1586 | 4to | The Englishemans treasure, or treasor for Englishmen: with the true Anatomye of mans body | John Windet for John Perin |

| 3rd: 1587 | 4to | [no change] | George Robinson for John Perin |

| 4th: 1596 | 4to | [no change] | Thomas Creede |

| 5th: 1599 | 4to | [no change] | Thomas Creede |

| 6th: 1613 | 4to | [no change] | Thomas Creede |

| 7th: 1626 | 4to | [no change] | B. Alsop and Tho. Fawcet |

| 8th: 1633 | 4to | [no change] | Bar. Alsop and Tho. Fawcet |

| 9th: 1641 | 4to | [no change] | B. Alsop and Tho. Fawcet |

| 10th: 1651 | 12mo | The surgions directorie, for young practitioners | T. Fawcet |

| Reprints | |||

| 1888 | 8vo | The anatomie of the bodie of man (eds) F J Furnivall and P Furnivall | N. Trübner for the Early English Text society |

| 1930 | 8vo | The English mans treasure | H. Milford, Oxford University, for the EETS |

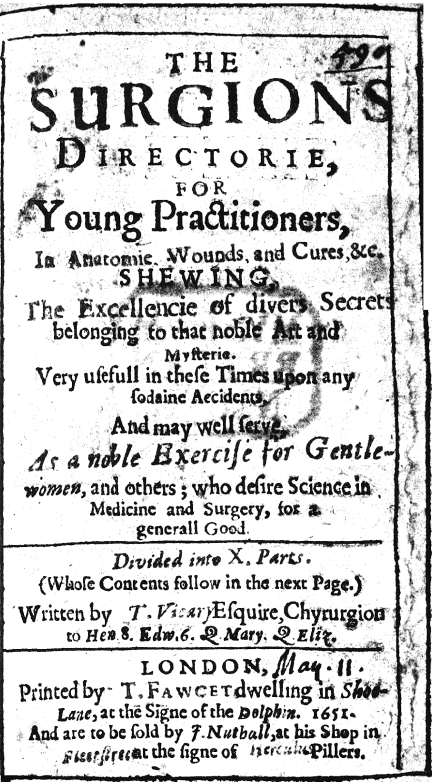

The next edition did not appear until 1613, and this is the longest interval between editions. The 1613 version is radically different from previous ones, not least because of its size (224 pages). In addition to the names of Vicary, Turner and Bremer, the initials of a fourth person (G.E.) appear on the title-page. Up to page 110, the layout of the work is similar to that of the 1596 edition. Thereafter, pages 111–222 contain a pharmacopoea entitled ‘Heeraftere followeth sundry Waters and Medicines, meete for Physicke, and Chyurgerie, As also Oyntments and Plaisters’. This is followed by a section with the title: ‘A Medicine for the Plague, and sickness of the Soule’. The book ends with a prayer, and has now acquired an eight-page index. It is obvious that the whole character of the work has changed. The Anatomie of Vicary is now less than a quarter of the contents, and was probably not a very important section. In the final edition the only name on the title-page is again Thomas Vicary, even though his contribution represents but a small part of the work; the names of Turner and Bremer no longer appear (Figure 4). Between 1577 and 1651 never more than fourteen years elapsed between successive editions, suggesting that the book was fulfilling some definite need.

Figure 4.

Title-page of the tenth edition, T Fawcet, London, 1651. The title has been changed to The surgions directorie, for young practitioners, and Thomas Vicary is listed as the sole author. (Courtesy of the British Library.)

The success of the earlier editions was probably due to the fact that the book was a compact and popular dissecting manual. However, the later continued success of The Englishemans treasure can have owed little to Vicary's Anatomie. It has been assumed by previous writers that the work was reprinted several times with certain additions, while remaining substantially as written by Vicary. This is clearly not the case, for only the 1577 edition is “pure” Vicary, and subsequent editions contain an increasing amount of other material having no connection with him. Several publishers printed the work over the years, each re-setting the type, but apart from minor spelling alterations, the anatomy content remained unchanged. By the time of the last edition, published as The surgions directorie, for young practitioners, Vicary's contribution was only a small part of the work. A quote from the preface indicates the purpose of the book at this stage in its history:

To all vertuous Ladyes and Gentlewomen of this Common-wealth of England, whose Goodnesse surpassing greatnesse, and desiring to Exercise themselves (as nursing Mothers) in the Art of Medicine and Surgery (especially in the remote parts of this Kingdome) where is neyther Physician nor Surgeon to bee had when sodaine Accidents happen; whereby the poorer sort of People many times perish for want of Advice.29

It is questionable whether any of the “poorer sort”, or even the wealthy sort, would have been much helped by some of the remedies proposed. However, the work joined a long list of publications in the latter part of the sixteenth century, where regimens, text-books and collections of remedies dominated the list of medical bestsellers.30 Whether “good master Vicary” would have recognized what was being published under his name is doubtful. Perhaps his reputation was such that, even many years after his death, it was still considered worthwhile to list him as the original author. A modern analogy would be Gray's anatomy, still so called even though the original author, Henry Gray, died in mid-Victorian times. In his list of medical bestsellers (1486–1604), Paul Slack lists thirteen books that went through seven to seventeen editions, with some 15 per cent of titles in the category of anatomy and surgery.31 On this basis, Vicary's work can be considered a bestseller.

In conclusion, a small anatomy book of 1577, largely abridged from an old manuscript, gradually changed into a work that was more in the nature of a “home doctor”. Although credited to Thomas Vicary, his contribution became an increasingly small part of the whole. Through ten editions and six different publishers, his name still appeared on the title-page, and while much else was added, the contents of the anatomy section remained unchanged. It seems remarkable that pre-Vesalian anatomy was still being published in England as late as the middle of seventeenth century. While Vicary fully deserves to be remembered for his role in establishing the Barber-Surgeons' Company, and for his work at the newly-refounded St Bartholomew's Hospital, he was not a Renaissance man and his solitary contribution to the surgical literature was out of date even when it was first published. Almost a hundred years after his death, Thomas Vicary's name still appeared on the title-page of a book that bore little relationship to what he had “devysed” in 1548. This seems an inordinately long life for a work of such unpretentious origins and one can only assume the prestige of his name was such that publishers continued to find it profitable to list him as the sole author of the work long after his death.

Footnotes

1 A profitable treatise of the Anatomie of mans body, compyled by … T.V. … Cheefe Chirurgion of S. Bartholomewes Hospital, which work is newly revyved by the chirurgions of the same hospital now beeing, London, H Bamforde, 1577; F J Furnivall and P Furnivall (eds), The anatomie of the bodie of man by Thomas Vicary … the edition of 1548, as re-issued by the surgeons of St Bartholomew's in 1577, Early English Text Society, No. 53, London, N Trübner, 1888; D'Arcy Power, ‘Thomas Vicary’, Br. J. Surg., 1918, 5: 359–62; Duncan P Thomas, ‘Thomas Vicary, barber-surgeon’, J. med. Biog., 2006, forthcoming.

2 Diary of John Manningham of the Middle Temple … 1602–1603, ed. John Bruce, Camden Society, No. 99, London, Camden Society, 1868, reprint, pp. 51–2.

3 Furnivall and Furnivall (eds), op. cit., note 1 above, p. v; Power, op. cit., note 1 above, p. 359.

4 Margaret Pelling and Charles Webster, ‘Medical practitioners’, in Charles Webster (ed.), Health, medicine, and mortality in the sixteenth century, Cambridge University Press, 1979, pp. 165–235, on p. 188.

5 J F Payne, ‘On an unpublished English anatomical treatise of the fourteenth century’, Br. med. J., 1896, i: 200–3.

6 Ibid., p. 200; S A J Moorat, Catalogue of western manuscripts on medicine and science in the Wellcome Historical Medical Library, London, Wellcome Historical Medical Library, 1962, vol. 1, pp. 439–42.

7 Robert Nels Mory, ‘A medieval English anatomy’, PhD thesis, University of Michigan, 1977.

8 Ibid., pp. 17, 12.

9 Ibid., pp. 37, 39.

10 Sanford Larkey, ‘The Vesalian compendium of Geminus and Nicholas Udall's translation: their relation to Vesalius, Caius, Vicary and de Mondeville’, The Library, 1933, 13: 367–94, pp. 374–50; Payne, op. cit., note 5 above, p. 200.

11 Wellcome Library, MS 564, p. 94.

12 Furnivall and Furnivall (eds), op. cit., note 1 above, pp. 12–13.

13 John Halle, A most excellent and learned woorke of chirurgie, called Chirurgia parva Lanfranci, Lanfranke [sic] of Mylayne his briefe, London, Thomas Marshe, 1565, unpaginated.

14 John Aiken, Biographical memoirs of medicine in Great Britain, London, Joseph Johnson, 1780, pp. 65–6.

15 Ibid., p. 65.

16 Ibid., p. 66.

17 Payne, op. cit., note 5 above, p. 203.

18 The ordre of the hospital of S. Bartholomewes, London, Richard Grafton, 1552; see also a reprint of the 1552 edition in The ordre of the Hospital of S. Bartholomowes in West-Smythfielde in London, London, The Hospital, 1997.

19 Record Office, Guildhall Rep. 12/2 f 449.

20 Larkey, op. cit., note 10 above, p. 370.

21 Harvey Cushing, Bio-bibliography of Andreas Vesalius, New York, Schuman's, 1943, p. 124.

22 Nicholas Udall, ‘The fyrste parte of thys treatise of anatomie wherein is conteyned a compendious or briefe rehersal of al and singuler the partes of mans bodie, etc.’, in Thomas Geminus, Compendiosa totius anatomie delineatio aere exarata, London, N Hyll for T Geminus, 1553, unpaginated.

23 Larkey, op. cit., note 10 above, pp. 376, 378–9.

24 Ibid., pp. 378–9.

25 Cushing, op. cit., note 21 above; Charles Singer, The evolution of anatomy, London, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1925.

26 Furnivall and Furnivall (eds), op. cit., note 1 above, p. 7.

27 Sidney Young, Annals of the Barber-Surgeons of London, London, Blades, East & Blades, 1890, p. 531, cited in Pelling and Webster, op. cit., note 4 above, p. 177.

28 Young, ibid., p. 312, cited in Andrew Wear, Knowledge and practice in English medicine, 1550–1680, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 231.

29 The surgions directorie, for young practitioners, in anatomie, wounds, and cures, &c., London, T Fawcet, 1651, preface.

30 Paul Slack, ‘Mirrors of health and treasures of poor men: the uses of the vernacular in medical literature of Tudor England’, in Webster (ed.), op. cit., note 4 above, pp. 237–73, on pp. 237, 248.

31 Ibid, p. 248.