Abstract

Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron is a prominent member of our normal adult intestinal microbial community and a useful model for studying the foundations of human–bacterial mutualism in our densely populated distal gut microbiota. A central question is how members of this microbiota sense nutrients and implement an appropriate metabolic response. B. thetaiotaomicron contains a large number of glycoside hydrolases not represented in our own proteome, plus a markedly expanded collection of hybrid two-component system (HTCS) proteins that incorporate all domains found in classical two-component environmental sensors into one polypeptide. To understand the role of HTCS in nutrient sensing, we used B. thetaiotaomicron GeneChips to characterize their expression in gnotobiotic mice consuming polysaccharide-rich or -deficient diets. One HTCS, BT3172, was selected for further analysis because it is induced in vivo by polysaccharides, and its absence reduces B. thetaiotaomicron fitness in polysaccharide-rich diet-fed mice. Functional genomic and biochemical analyses of WT and BT3172-deficient strains in vivo and in vitro disclosed that α-mannosides induce BT3172 expression, which in turn induces expression of secreted α-mannosidases. Yeast two-hybrid screens revealed that the cytoplasmic portion of BT3172's sensor domain serves as a scaffold for recruiting glucose-6-phosphate isomerase and dehydrogenase. These interactions are a unique feature of BT3172 and specific for the cytoplasmic face of its sensor domain. Loss of BT3172 reduces glycolytic pathway activity in vitro and in vivo. Thus, this HTCS functions as a metabolic reaction center, coupling nutrient sensing to dynamic regulation of monosaccharide metabolism. An expanded repertoire of HTCS proteins with diversified sensor domains may be one reason for B. thetaiotaomicron's success in our intestinal ecosystem.

Keywords: Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, glycoside hydrolases, gut microbial ecology, metabolic regulation, signal transduction

The adult human gut is home to tens of trillions of microbes. This community is composed primarily of members of the domain Bacteria but also contains representatives from Archaea and Eukarya (1). Most bacteria live in the colon where, among their other functions, they extract energy from dietary polysaccharides that would otherwise be lost because our human genome does not encode the requisite glycoside hydrolases and polysaccharide lyases needed for cleaving their glycosidic linkages (2, 3). Intestinal absorption of the short-chain fatty acid end products of microbial polysaccharide fermentation accounts for up to 10% of our daily harvest of calories (4). Two divisions of bacteria, the Bacteroidetes which include the saccharolytic Bacteroides, and the Firmicutes, account for >99% of all phylogenetic types (phylotypes) identified in the colon (5).

Several recent developments have set the stage for defining the structure and operations of this community. Comprehensive 16S rRNA sequence-based enumerations combined with new computational methods are allowing community membership to be defined and compared between healthy individuals (5, 6). Sequencing individual representatives of the major divisions of bacteria as well as whole community DNA is revealing the gene content of the gut “microbiome” and will allow in silico predictions to be made of the microbiota's metabolic potential (7). Germ-free (GF) mice, colonized with one or more sequenced representatives of the human gut microbiota, are providing insights about the transcriptional and metabolic networks expressed by community members in their habitats (3).

One important question about the operation of this microbial community is how its members respond to changes in their nutrient environments. Subsumed under this question is the issue of how these microbes sense the nutrient landscape of their gut habitats and adapt to changes in resource availability. The answers could help us to attribute niches (professions) to community members, understand how a microbiota is selected, elucidate how community robustness is maintained, and develop strategies for intentionally manipulating the operations of the gut microbiota so as to provide additional benefits to human hosts. One benefit could be a new era of personalized nutrition where diet is matched to the nutrient processing capacity of an individual's microbiota.

We have used Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron as a model gut symbiont to address some of these issues. In the most comprehensive 16S rRNA enumeration study of the human gut microbiota published to date, this Gram-negative obligate anaerobe comprised 12% of all Bacteroidetes, and 6% of all colonic bacteria in three healthy adults (5). The B. thetaiotaomicron genome sequence (8) revealed an unprecedented expansion of genes dedicated to polysaccharide metabolism: its “glycobiome” (genes involved in carbohydrate acquisition and processing) includes an arsenal of 226 glycoside hydrolases and 15 polysaccharide lyases capable of cleaving many of the glycosidic linkages present in plant glycans that are not digestible by humans (3, 8, 9).

The B. thetaiotaomicron genome also contains a sizeable collection of genes involved in environmental sensing and signal transduction. This collection includes 54 sensor kinases and 29 response regulators (8) that form “classical” two-component systems, plus a family of 32 unique proteins that incorporate all of the domains found in classical two-component systems into a single polypeptide. Classical two-component systems transduce signals from the cell's outside environment (pH, ions, and metabolites) to its genome via a multistep phosphorelay. The prototypic two-component system consists of (i) a membrane-localized sensor protein containing histidine kinase and phosphoacceptor domains (annotated as HATPase_c and HisKA in the Pfam database; http://pfam.wustl.edu/), and (ii) a cytoplasmic response regulator protein containing a response regulator receiver domain (Response_reg) and a signal output domain (10). The majority of response regulators are transcription factors that contain one of three types of DNA-binding domains (trans_reg_c, GerE, or HTH_8). B. thetaiotaomicron's 32 “hybrid two-component system” (HTCS) proteins are composed of an N-terminal periplasmic sensor that is interrupted by up to five predicted transmembrane segments, plus four conserved cytoplasmic domains [HisKA, HATPase_c, Response_reg, plus a helix–turn–helix putative DNA-binding domain (HTH_AraC) that is distinct from the HTH_8 domain common to classical response regulators]. The sensor domains of HTCS proteins are less highly conserved among family members than their intracellular signaling domains (19% vs. 32% average amino acid sequence identity, respectively), suggesting that HTCS proteins have diversified to respond to distinct signals but have conserved their method of intracellular signal transduction.

B. thetaiotaomicron has more HTCS proteins than any other sequenced prokaryote: since their initial identification in the B. thetaiotaomicron genome, HTCS family members have been identified in other Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Chloroflexi (ref. 11 and Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Intriguingly, 17 of B. thetaiotaomicron's HTCS genes are located adjacent to genes encoding paralogs of SusC/SusD polysaccharide-binding proteins, or glycoside hydrolases (8). Based on these findings, we have hypothesized that evolution of a large collection of HTCS paralogs may be a salient feature of the adaptation of B. thetaiotaomicron (and other Bacteroidetes) to their gut habitats (addresses) and niches (12). Below, we present evidence that supports this hypothesis.

Results and Discussion

BT3172 Expression Improves the Fitness of B. thetaiotaomicron in the Ceca of Mice Fed a Polysaccharide-Rich (PR) Diet.

We used custom Affymetrix GeneChips containing probesets that recognize 98.7% of B. thetaiotaomicron's 4,779 known or predicted chromosomal protein-coding genes to characterize HTCS gene expression in three nutrient environments: (i) during growth from early log to stationary phase in a batch culture fermenter containing a minimal medium (MM) with 0.5% glucose (MM-G) as the sole fermentable carbon source; (ii) in the ceca of adult male GF mice belonging to the NMRI inbred line that were fed a standard autoclaved PR rodent chow diet and colonized with B. thetaiotaomicron for 10 days (a period that encompasses 2–3 rounds of turnover of the gut epithelium and its overlying mucus layer); and (iii) in the ceca of GF mice that were switched from a PR diet to a simple sugar diet (35% glucose/35% sucrose; GS) devoid of polysaccharides for 14 days before being colonized with B. thetaiotaomicron for 10 days (n = 3–5 mice per treatment group; each cecal sample was analyzed independently with a GeneChip). The cecum was selected because this anatomically distinct region, located between the small intestine and colon, contains a large bacterial population that is readily harvested. We have shown that the density of colonization of the ceca of mice in groups ii and iii is not significantly different (1011–1012 colony forming units/ml luminal contents), and that removing polysaccharides from the diet causes B. thetaiotaomicron to redirect its glycan foraging to the mucus overlying the cecal epithelium, with attendant induction of genes that degrade host-derived glycans (e.g., sialidases, fucosidases, β-hexosaminidases, and a mucin-desulfating sulfatase; see ref. 3)

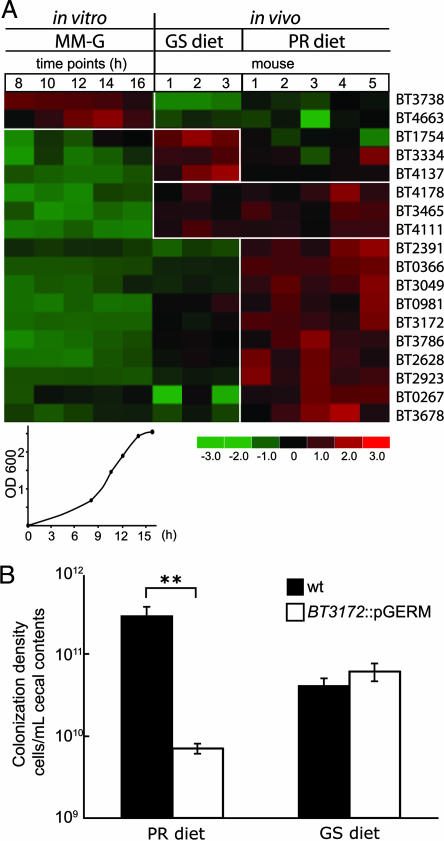

Our GeneChip analysis revealed that 18 of the 32 HTCS family members have significantly different levels of expression among the three growth conditions tested [P < 0.01; empirical false discovery rate, 0%]. These differentially regulated HTCS genes cluster into four groups: (i) highest expression in MM-G (two HTCS); (ii) highest expression in the ceca of mice on the GS diet (three); (iii) highest expression in the ceca of animals on the PR diet (ten); and (iv) highest expression in mice on both diets compared with MM-G (three) (Fig. 1A). The distal human gut, like the ceca of our gnotobiotic mice, normally provides an environment rich in polysaccharides for B. thetaiotaomicron. Therefore, we chose BT3172 for further analysis because it represents the group of HTCS genes that are most highly expressed in the ceca of mice on the PR diet (10-fold higher levels than in MM-G at mid-log phase; 2-fold higher compared with GS diet-treated animals; P < 0.01; Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Effects of nutrient environment on expression of B. thetaiotaomicron genes encoding hybrid two-component proteins in vitro and in the ceca of gnotobiotic mice. (A) GeneChip profiling of HTCS gene expression during growth of WT B. thetaiotaomicron in a batch culture fermenter containing MM-G or collected from the cecal contents of monoassociated mice fed a GS diet or a PR diet (n = 3 and 5 animals, respectively; each analyzed separately). Cells were harvested at five time points during growth from log to stationary phase in MM-G (n = 2 samples per time point). Four patterns of HTCS expression are observed; those that are either most highly expressed in MM-G, in vivo on a GS diet, in vivo on a PR diet, or in vivo on both diets compared with MM-G. Colors indicate standard deviation above (red) and below (green) the mean level of expression (black) of a gene across all conditions. (B) Cocolonization of GF mice gavaged once with equivalent numbers of isogenic WT and BT3172::pGERM strains and killed 10 days later. Loss of BT3172 reduces levels of cecal colonization in animals fed a PR but not a GS diet. Mean values ± SEM are plotted. ∗∗, P < 0.01.

A mixture of 108 colony forming units of WT B. thetaiotaomicron and 108 colony forming units of an isogenic mutant containing a BT3172-null allele (BT3172::pGERM; erythromycin resistant) was introduced by gavage into 10 12-week-old GF NMRI male recipients. Five animals were maintained on a PR diet. The second group had been switched from PR to GS chow 14 days before colonization. Both groups of gnotobiotic mice were killed 10 days after gavage, and the number of viable WT vs. mutant cells in their cecal contents was defined by selective plating. In the PR diet-fed group, WT B. thetaiotaomicron achieved a statistically significant 40-fold higher density than the mutant (P < 0.01 using Student's t test), whereas in the GS-fed group, both strains colonized the cecum at equivalent levels (Fig. 1B). Colonization of mice consuming one or the other diets with the WT or the mutant strain alone resulted in equivalent numbers of colony forming units (P > 0.2 among treatment groups). Control experiments confirmed that there was no detectable reversion of the mutant to WT in vivo under either nutrient condition (<10−6) as defined by an erythromycin-resistant phenotype, and that the fitness defect observed with BT3172::pGERM was not due to the insertion of the suicide vector (pGERM) itself [co-colonizations with WT B. thetaiotaomicron and an isogenic mutant strain lacking an HTCS whose expression is similar in mice fed PR and GS diets (BT4178::pGERM) produced equivalent levels of colonization of both strains in the ceca of PR diet-treated animals (data not shown)]. Based on these results, we concluded that BT3172 plays a role in successful B. thetaiotaomicron colonization of its cecal habitat when organisms are competing for dietary polysaccharides.

Loss of BT3172 Affects α-Mannosidase Gene Expression.

To obtain a comprehensive view of the impact of BT3172 deficiency on the B. thetaiotaomicron transcriptome, we performed GeneChip profiling of WT and BT3172::pGERM harvested from the ceca of GF mice that had been colonized for 10 days with either strain while consuming a PR or GS diet (n = 5 mice per treatment group per strain). Hierarchical clustering of all genes revealed that the BT3172::pGERM data set obtained from mice on the PR diet clustered more closely with the WT B. thetaiotaomicron PR diet data set than with the BT3172::pGERM GS data set (Fig. 5A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These findings underscore the impact of diet on the B. thetaiotaomicron transcriptome.

Comparison of WT and mutant B. thetaiotaomicron harvested from the ceca of PR diet-treated animals revealed statistically significant differences in the expression of 686 genes (14% of the genome): 440 genes were up-regulated in BT3172::pGERM relative to WT, whereas 246 genes were down-regulated [P < 0.01; false discovery rate, ≤0.4%; see Fig. 5 B and C and Table 2, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, for a Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG)-based categorization of regulated genes]. The absence of a BT3172 transcript did not produce statistically significant difference in the expression of any other HTCS family member. COG M (cell wall/membrane biogenesis, includes genes involved in capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis) and COG G (carbohydrate transport and metabolism, includes glycoside hydrolases) represented the dominant functional categories of responses to BT3172 deficiency.

Mannans (polymannose containing glycans) and mannosides (d-mannose connected to other sugars by various glycosidic linkages) are abundantly represented in dietary plant glycans (mainly as β-linked mannose residues) and in fungal and mammalian glycans (primarily as α-linked mannose). Our genome contains no mannanases and 16 mannosidases (15 α-mannosidases and 1 β-mannosidase). The carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZy) database (www.cazy.org; see ref. 2) divides B. thetaiotaomicron's 241 glycoside hydrolases and polysaccharide lyases into 45 families. B. thetaiotaomicron is well equipped to liberate both α- and β-anomers of mannose: it possesses 25 α-mannosidases, 10 α-mannanases, and 5 β-mannosidases.

Glycoside hydrolase family 92 was most affected by loss of BT3172 (see Fig. 6A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). This family contains 23 members, all of which are predicted to be α-mannosidases capable of cleaving disaccharides or more complex glycans with terminal mannose residues. Loss of BT3172 significantly reduced expression of five family 92 α-mannosidases in vivo: two of the genes encoding these enzymes are in a single operon (BT3962 and BT3963; see Fig. 6 B and C). Loss of BT3172 did not affect expression of B. thetaiotaomicron's 10 mannanases.

The Effect of BT3172 Deficiency on Capsular Polysaccharide Locus Gene Expression in Vivo Indicates a Defect in Sensing Polysaccharides.

The B. thetaiotaomicron genome contains eight capsular polysaccharide synthesis (CPS) loci, each composed of genes involved in the decoration of the microbe's surface with polysaccharides. Elegant work by Comstock and coworkers (13) has shown that by regulating CPS locus expression Bacteroides fragilis can match its surface glycan features with the glycan landscape of its habitat. This molecular mimicry may help Bacteroides species evade a host immune response.

Transcription profiling of WT B. thetaiotaomicron revealed that CPS3 (BT0595–BT0614) is normally expressed at higher levels than the other CPS loci when polysaccharides are scarce (i.e., during growth in MM-G) and is down-regulated when cells are (i) exposed to tryptone/yeast extract/glucose (TYG) medium, which is rich in α-linked mannans as well as other Saccharomyces cerevisiae-derived polysaccharides, or (ii) reside in the ceca of mice consuming a PR diet. In contrast, CPS4 (BT1336–BT1358) is selectively up-regulated under conditions in which polysaccharides are abundant (i.e., in the ceca of mice fed a PR diet and in TYG medium) and is down-regulated in MM-G (ref. 3 and data not shown).

B. thetaiotaomicron containing the BT3172::pGERM allele has the opposite pattern of expression of CPS3: it up-regulates this locus relative to WT during growth in TYG (a 3.1-fold increase in the aggregate signal produced by all probesets that recognize the products of CPS3; P < 0.001) and in the ceca of mice fed a PR diet (a 4.6-fold increase in the aggregate signal; P < 0.001; see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). This aberrant pattern of CPS3 expression suggests that removal of BT3172 causes B. thetaiotaomicron to “misinterpret” its nutrient landscape as being polysaccharide-deficient when it is replete with glycans.

Loss of BT3172 Produces a Change in Prioritized Utilization of Glycans.

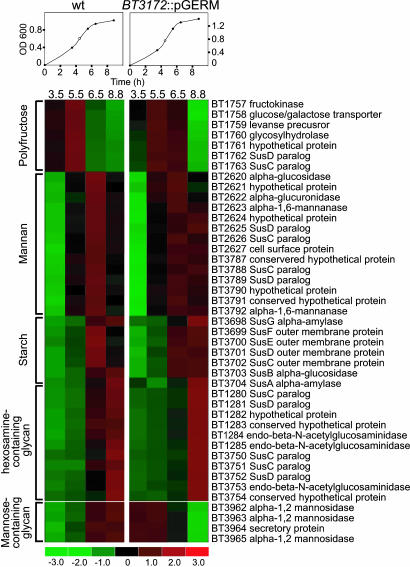

GeneChip profiling of WT B. thetaiotaomicron during growth from log to stationary phase in TYG medium disclosed a prioritized pattern of glycan utilization; it first expresses glycoside hydrolases that liberate fructose from fructans, followed by enzymes that degrade mannans, then starch, and finally hexosamine-containing glycans (Fig. 2). These findings indicate that WT B. thetaiotaomicron prioritizes expression of genes involved in the acquisition of carbohydrates that are most easily shunted into the glycolytic pathway (i.e., fructose and mannose). Consistent with this notion, the WT strain up-regulates genes involved in glycolysis in the early log phase and down-regulates these genes as it approaches stationary phase (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 2.

The prioritized pattern of glycan utilization by B. thetaiotaomicron is disrupted by BT3172::pGERM. GeneChip analysis of glycoside hydrolase-containing operons that display differential expression in WT B. thetaiotaomicron during growth from log to stationary phase in rich (TYG) medium is shown. The orderly pattern of induction and suppression of expression provides insights about the prioritization of glycan consumption: fructans are consumed initially, followed by mannans, starch, and finally hexosamine-containing glycans. Note that an operon involved in the degradation of mannose-containing glycans and import of liberated mannose (BT3962–BT3965) is induced prematurely during early log phase in the BT3172::pGERM strain.

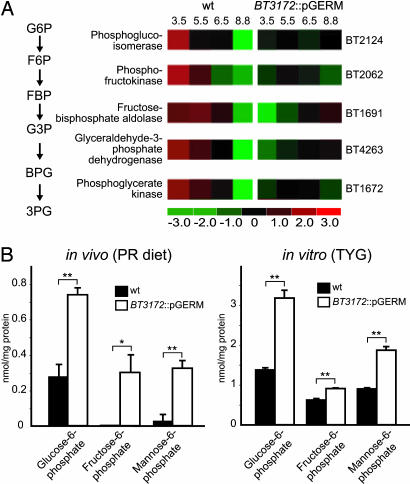

Fig. 3.

The absence of BT3172 impairs glycolysis. (A) GeneChip analysis of the expression of genes in the glycolytic pathway during growth of isogenic WT and BT3172::pGERM strains in batch culture fermenters containing TYG medium. (B) Concentration of metabolites in WT and mutant B. thetaiotaomicron strains harvested from the cecal contents of gnotobiotic mice fed a PR diet or during mid-log phase growth in a fermenter containing TYG medium. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01

BT3172::pGERM shows a similar pattern of nutrient utilization in TYG medium, with the exception that an operon (BT3962–BT3965), containing three CAZy family 92 α-mannosidases, is up-regulated during the early log phase rather than the late log/stationary phase (Fig. 2). The lack of a discernible growth defect of the mutant in vitro and in monoassociation experiments contrasts with its reduced fitness in the face of competition with WT in vivo (Fig. 1A). These data are consistent with the notion that there is functional redundancy in B. thetaiotaomicron's nutrient sensing and acquisition machinery that effectively compensates for loss of BT3172 except in highly competitive situations.

The mutant exhibits a constant level of expression of glycolytic genes so that compared with WT, their expression is lower in the early log phase and higher in the late log and stationary phase (Fig. 3A). Biochemical assays disclosed that glucose 6-phosphate and fructose 6-phosphate levels are significantly higher in the mutant compared with the WT strain during mid-log-phase growth in TYG medium and in the ceca of mice fed a PR diet (Fig. 3B), consistent with reduced glycolytic pathway activity in the absence of BT3172. (The presence of these metabolites in cecal contents could be attributed to B. thetaiotaomicron because they were below the limit of detection in cecal contents harvested from GF controls fed the same diet; data not shown).

Mannose enters the glycolytic pathway via the action of two enzymes, a hexokinase (BT2430), which phosphorylates mannose to mannose 6-phosphate, and mannose 6-phosphate isomerase (BT0373), which converts mannose 6-phosphate to fructose 6-phosphate. GeneChip profiling of BT3172::pGERM and WT B. thetaiotaomicron disclosed no statistically significant differences in the expression of genes encoding either enzyme, both in vitro and in vivo. However, mannose 6-phosphate levels were significantly elevated in the mutant strain, in vitro (mid-log-phase cells) and in vivo (Fig. 3B). This elevation is consistent with the observed increase in fructose 6-phosphate and/or reduction in glycolysis.

BT3172 Expression Is Activated by Mannosides but Not by Monomeric d-Mannose.

These findings indicated that loss of BT3172 disrupts B. thetaiotaomicron's pattern of mannoside utilization and raised the question of whether expression of this HTCS is regulated by mannosides. Therefore, we used quantitative RT-PCR (see Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, for a list of all primers used for quantitative RT-PCR) to measure BT3172 mRNA levels during mid-log-phase growth in MM containing yeast extract (rich in α-linked mannans) or 0.5% mannan. BT3172 expression is induced to similar degrees in MM–yeast extract and MM–yeast mannan compared with MM-G (4.5 ± 0.5- and 5.8 ± 1.1-fold). Although, MM containing 0.5% d-mannose was not able to induce BT3172, MM plus 0.5% α1,3-mannobiose up-regulated BT3172 4.0 ± 0.6-fold above MM-G controls. Together, these data reveal that α-linked mannosides, but not monomeric mannose, modulates BT3172 expression.

Comparison of mid-log-phase WT and BT3172:pGERM strains grown in MM–α1,3-mannobiose disclosed that loss of BT3172 reduces expression of the two CAZy-group 92 α-mannosidases contained in a single operon (BT3962 and BT3963) by 3.3 ± 0.5- and 5.6 ± 0.9-fold, respectively (P < 0.001). These two genes also show reduced expression in the ceca of mice fed a PR diet when BT3172 is missing. Thus, our results reveal a positive feedback loop in which mannose present in glycosidic linkages induces BT3172 expression. BT3172, in turn, induces expression of the α-mannosidases that degrade these mannosides. Glycosidic linkage-dependent regulation of gene expression is known to occur in B. thetaiotaomicron's starch utilization system (Sus) operon, which is induced by maltose and higher order starches, but not by glucose alone (14). Linkage-specific activation is consistent with the idea that at least some B. thetaiotaomicron HTCS incorporate all of their input and output domains into one polypeptide so that they can sense very specific nutrients in their habitat and mobilize appropriate cellular transcriptional and metabolic responses without the need for signal amplification. One way to coordinate such responses would be to assemble enzymes involved in processing the products of HTCS-regulated glycoside hydrolases on the HTCS itself: i.e., the HTCS would serve as a scaffold for bringing enzymes and their substrates together to form a multicomponent metabolic machine.

The Sensor Domain of BT3172 Interacts with Enzymes Involved in Glucose Metabolism.

To search for protein partners of BT3172, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen using the N-terminal sensor domain (Met-1-Glu-745) of BT3172 as bait and the protein products of a B. thetaiotaomicron cDNA library as preys. This cDNA library, containing 330,000 clones, was prepared from RNA isolated from B. thetaiotaomicron harvested during growth in TYG and MM-G at all of the time points shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The cDNA library of preys was screened at 6-fold coverage by using the strict selection criteria described in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Our screen yielded two cytoplasmic proteins that interact with BT3172's sensor domain: (i) glucose 6-phosphate isomerase (BT2124, Gly-228-Gly-352), which produces fructose 6-phosphate, the substrate for phosphofructokinase (rate-limiting enzyme in glycolysis) and (ii) glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (BT1221, Thr-309-Gly-464), which catalyzes the first committed step of the pentose phosphate pathway. A third interacting protein was identified (BT0924, Trp-77-Gly-152) that shares homology to ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter substrate-binding proteins. BT0924 is part of an operon that also encodes an ABC transporter ATP-binding protein and an ABC transporter permease. Loss of BT3172 does not affect the expression of this operon in vitro or in vivo. Directed yeast two-hybrid screens revealed that BT0924 also interacts with the sensor domains of two other HTCS proteins (BT026 and BT3302). Based on these findings, we focused on our subsequent analyses on the significance of the interactions between BT3172 and the two cytoplasmic enzymes involved in glucose metabolism.

Although loss of BT3172 affects glycolytic activity, it does not appear to affect the pentose phosphate pathway. Enzymes catalyzing the first three steps in this pathway (glucose 6-phosphate → glucono 1,5-lactone 6-phosphate → 6-phosphogluconate → ribulose 5-phosphate) are all encoded by genes contained in a single operon (BT1220–BT1222). None of these genes are differentially expressed in the WT compared with BT3172::pGERM strains, in vitro or in vivo, nor are there statistically significant differences in the levels of 6-phosphogluconate, an intermediate in this pathway (data not shown).

Interactions Between BT3172 and These Two Proteins Are Specific for This HTCS and Limited to a Discrete Cytoplasmic Region of Its Sensor Domain.

Follow-up, directed, yeast two-hybrid assays established that the BT3172 sensor domain interacted with the intact isomerase and dehydrogenase. BT2124 and BT1221 were subsequently screened against the sensor domains of 29 other HTCS proteins (Table 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The results demonstrated that the interactions between the isomerase and dehydrogenase were specific for the BT3172 sensor domain.

To identify the region of BT3172's sensor domain responsible for these protein–protein interactions, four truncation mutants were constructed: Met-1-Asn-601, Met-1-Pro-451, Met-1-Ser-299, and Met-1-Lys-145. The isomerase and dehydrogenase interacted with Met-1-Ser-299 but not Met-1-Lys-145, implying that Asp-146-Ser-299 is the critical BT3172 domain. This conclusion was further validated by replacement of Asp-146-Ser-299 in BT3172 with the analogous region of another HTCS (Lys-145-Ser-298 of BT4137): the substitution resulted in the loss of BT3172's ability to interact with all three protein partners.

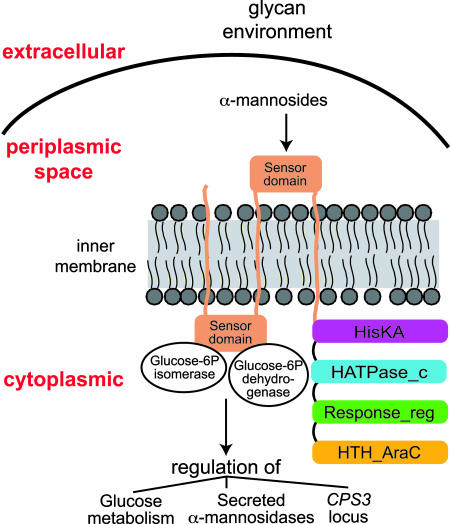

Glucose 6-phosphate isomerase and glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase are cytoplasmic proteins. The program tmpred (www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html) predicts three transmembrane segments in the sensor domain of BT3172 (Leu-5-Ala-25, Val-393-Ala-41, and Thr-755-Ile-771), resulting in its subdivision into periplasmic and cytoplasmic components. The region of BT3172 sensor domain that interacts with the isomerase and dehydrogenase (Arg-146-Ser-299) is predicted to be located on the cytoplasmic face of the inner membrane (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Model of BT3172-directed metabolic regulation. B. thetaiotaomicron has 32 HTCS proteins that incorporate the elements of classical two-component signaling proteins [a sensor, phosphoacceptor (HisKA), histidine kinase (HATPase_c), response regulator receiver (Response_reg), and signal output domain] in one polypeptide. Structural diversity among HTCS proteins is greatest among their sensor domains. This domain in BT3172 (Met-1-Glu-745) contains three predicted transmembrane spanning elements, producing periplasmic- and cytoplasmic-facing elements. Expression of BT3172 is induced by mannosides; the HTCS, in turn, induces expression of α-mannosidases required for breakdown of mannosides. Asp-146-Ser-299 of the cytoplasmic portion of BT3172's sensor domain serves as a site for binding two proteins: glucose 6-phosphate isomerase (EC 5.3.1.9; key enzyme in the glycolytic pathway) and glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.49; catalyzes the first step in the pentose phosphate shunt). Loss of BT3172 diminishes glycolytic pathway activity in vivo and in vitro. The organization of BT3172 and its interacting partners links sensing the availability of carbohydrates in the environment with regulation of bacterial carbohydrate metabolism.

Yeast two-hybrid screens using the predicted periplasmic face of BT3172's sensor domain (Gly-421-Glu-745) as bait did not identify any interacting proteins. Screens using the entire intracellular portion of BT3172 (Lys-827-Ile-1310) or just its histidine kinase, phosphotransfer, response regulator, or helix-turn-helix domains, also failed to identify any interacting proteins that satisfied our stringent selection criteria.

Prospectus.

GeneChip studies of B. thetaiotaomicron grown in vitro in MM-G and TYG media or harvested from the ceca of mice fed a PR-diet, have shown that B. thetaiotaomicron constitutively expresses, at least at low levels, members of all of its glycoside hydrolase families (secreted and cytoplasmic), as well as a majority of its SusC/D paralogs (3). These products of the B. thetaiotaomicron glycobiome presumably allow the organism to constantly survey and import samples of glycans present in its gut habitat into its periplasmic space where metabolic responses are initiated. Our analysis of the operations of BT3172, summarized in Fig. 4, supports this view. The presence of mannosides induces BT3172 expression, either through their direct interaction with this HTCS or with other cellular signaling proteins. BT3172 induction by mannosides, in turn, induces expression of secreted α-mannosidases that aid in the harvest of the perceived nutrient. The cytoplasmic portion of BT3172's sensor domain serves as a scaffold for recruiting two key enzymes that regulate metabolism of monosaccharides generated from harvested carbohydrates. Interaction with these enzymes is a unique characteristic of this B. thetaiotaomicron HTCS and specific for a common region of the cytoplasmic face of its sensor domain. Regulation of these site-specific protein–protein interactions would provide a means for B. thetaiotaomicron to dynamically couple carbohydrate availability with utilization. The role of the phosphorelay system incorporated into BT3172 in modulating these protein–protein interactions, or in communicating with other signaling molecules remains to be defined, as does the role of its C-terminal helix–turn–helix (HTH_AraC) domain. Metabolic intermediates may themselves be important mediators of BT3172–protein interactions.

B. thetaiotaomicron contains the largest collection of HTCS among sequenced human gut-associated Bacteroides, both in turns of absolute number and when corrected for genome size. The B. thetaiotaomicron genome also encodes the largest collection of glycoside hydrolases and polysaccharide lyases among sequenced Bacteroides, suggesting that its evolved collection of HTCS paralogs, with their structurally diversified sensor domains, provides a means for controlling its elaborate glycan processing apparatus in an integrated and responsive manner. These features could explain B. thetaiotaomicron's abundant representation in our densely populated, competitive distal gut ecosystem. Identifying the ligands recognized by HTCS sensor domains may provide a starting point for developing strategies for intentionally manipulating the biological activities of B. thetaiotaomicron and perhaps other Bacteroides in vivo and for matching diet to B. thetaiotaomicron's niche.

Materials and Methods

Generation and Growth an Isogenic BT3172::pGERM Mutant.

The methods used for targeted disruption of BT3172 and growth of WT and mutant strains in a BioFlo-110 batch culture fermentor under defined nutrient conditions are similar to those reported in earlier publications for other B. thetaiotaomicron genes and strains (3, 15). Further details can be found in Supporting Text.

GF Mice.

All experiments employing mice were performed using protocols approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee. NMRI-KI mice were maintained in plastic gnotobiotic isolators (16) under a strict 12-h light cycle. Animals were fed a standard autoclaved chow diet (B & K Universal, Hull, U.K.) or an irradiated diet composed of 35% (wt/wt) glucose, 35% sucrose, and 20% protein (Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ). For further details about colonization and purification of RNA from and analyses of metabolites in cecal contents, see Supporting Text.

GeneChip Analysis.

cDNA targets were prepared from both in vivo and in vitro RNA samples by using protocols described in the E. coli Antisense Genome Array manual (Affymetrix). The cDNA product was isolated (QiaQuick Spin columns; Qiagen, Valencia, CA), fragmented (DNase-I; Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences), biotinylated (bioArray Terminal Labeling Kit; Enzo) and hybridized to custom B. thetaiotaomicron GeneChips (3).

Yeast Two-Hybrid Screens.

A B. thetaiotaomicron cDNA library was produced by using the Matchmaker Library Construction kit and the GAL4 activation domain fusion vector (BD Biosciences). RNA was prepared from samples obtained during growth of WT B. thetaiotaomicron from log to stationary phase in batch culture fermenter vessels containing TYG or MM-G. For further details about the screen, see Table 4 and Supporting Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank David O'Donnell, Maria Karlsson, Janaki Guruge, and Sabrina Wagoner for invaluable assistance with experiments involving gnotobiotic mice. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK30292 and DK52574.

Abbreviations

- GF

germ-free

- HTCS

hybrid two-component system

- MM

minimal medium

- MM-G

MM with 0.5% glucose

- PR

polysaccharide-rich

- CPS

capsular polysaccharide synthesis

- TYG

tryptone/yeast extract/glucose

- GS

35% glucose/35% sucrose.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- 1.Ley R. E., Peterson D. A, Gordon J. I. Cell. 2006;124:837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coutinho P. M., Henrissat B. In: Recent Advances in Carbohydrate Bioengineering. Gilbert H. J., Davies G., Henrissat B., Svensson B., editors. Cambridge, U.K.: R. Soc. Chem.; 1999. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonnenburg J. L., Xu J., Leip D. D., Chen C. H., Westover B. P., Weatherford J., Buhler J. D, Gordon J. I. Science. 2005;307:1955–1959. doi: 10.1126/science.1109051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Backhed F., Ley R. E., Sonnenburg J. L., Peterson D. A., Gordon J. I. Science. 2005;307:1915–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckburg P. B., Bik E. M., Bernstein C. N., Purdom E., Dethlefsen L., Sargent M., Gill S. R, Nelson K. E., Relman D. A. Science. 2005;308:1635–1638. doi: 10.1126/science.1110591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ley R. E., Backhed F., Turnbaugh P, Lozupone C. A, Knight R. D., Gordon J. I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:11070–11075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill S. R., Pop M., DeBoy R. T., Eckburg P. B., Turnbaugh P., Samuel B. S., Gordon J. I., Relman D. A., Fraser-Liggett C. M., Nelson K. E. Science. 2006 doi: 10.1126/science.1124234. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu J., Bjursell M. K., Himrod J., Deng S., Carmichael L. K., Chiang H. C., Hooper L. V., Gordon J. I. Science. 2003;299:2074–2076. doi: 10.1126/science.1080029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salyers A. A., Vercellotti J. R., West S. E., Wilkins T. D. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1977;33:319–322. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.2.319-322.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stock A. M., Robinson V. L., Goudreau P. N. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:183–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyazaki K., Miyamoto H., Mercer D. K., Hirase T., Martin J. C., Kojima Y., Flint H. J. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:2219–2226. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2219-2226.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu J., Chiang H. C, Bjursell M. K., Gordon J. I. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coyne M. J, Reinap B., Lee M. M., Comstock L. E. Science. 2005;307:1778–1781. doi: 10.1126/science.1106469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Elia J. N., Salyers A. A. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:7180–7186. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7180-7186.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooper L. V., Xu J., Falk P. G., Midtvedt T., Gordon J. I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:9833–9838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hooper L. V., Mills J. C., Roth K. A., Stappenbeck T. S., Wong M. H., Gordon J. I. In: Molecular Cellular Microbiology. Sansonetti P., Zychlinsky A., editors. Vol. 31. San Diego: Academic; 2002. pp. 559–589. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.