Abstract

Isolated from Pseudomonas resinovorans CA10, pCAR1 is a 199-kb plasmid that carries genes involved in the degradation of carbazole and dioxin. The nucleotide sequence of pCAR1 has been determined previously. In this study, we characterized pCAR1 in terms of its replication, maintenance, and conjugation. By constructing miniplasmids of pCAR1 and testing their establishment in Pseudomonas putida DS1, we show that pCAR1 replication is due to the repA gene and its upstream DNA region. The repA gene and putative oriV region could be separated in P. putida DS1, and the oriV region was determined to be located within the 345-bp region between the repA and parW genes. Incompatibility testing using the minireplicon of pCAR1 and IncP plasmids indicated that pCAR1 belongs to the IncP-7 group. Monitoring of the maintenance properties of serial miniplasmids in nonselective medium, and mutation and complementation analyses of the parWABC genes, showed that the stability of pCAR1 is attributable to the products of the parWAB genes. In mating assays, the transfer of pCAR1 from CA10 was detected in a CA10 derivative that was cured of pCAR1 (CA10dm4) and in P. putida KT2440 at frequencies of 3 × 10−1 and 3 × 10−3 per donor strain, respectively. This is the first report of the characterization of this completely sequenced IncP-7 plasmid.

In the past 30 years, many plasmids carrying genes for enzymes that degrade organic xenobiotics have been isolated (reviewed in references 9, 41, 42, and 69). The most detailed analyses have been conducted on the toluene/xylene-degradative plasmid pWW0 (20, 37, 70, 71) and the 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-degradative plasmid pJP4 (11, 12, 65). These two plasmids belong to incompatibility (Inc) groups P-9 and P-1β, respectively, which contain many other degradative plasmids, such as NAH7 (IncP-9) (13), pADP-1 (IncP-1β) (10, 36), pDTG1 (IncP-9) (9, 54), pUO1 (IncP-1β) (30, 59), and SAL1 (IncP-9) (7). These are mobile genetic elements that spread various degradative genes in the environment (26, 60).

Plasmid pCAR1 is involved in the degradation of carbazole (CAR), which is a xenobiotic azarene compound composed of a dibenzopyrrole ring. pCAR1 was isolated from the CAR-degrading bacterium Pseudomonas resinovorans CA10 (40, 43). The CAR-catabolic enzymes encoded by pCAR1 can also degrade dibenzo-p-dioxin and dibenzofurans, which are the parental compounds of dioxins (21, 39, 50). Previously, we reported the following characteristics of pCAR1: (i) this 199.035-kb plasmid carries the 72.8-kb class II transposon Tn4676, which contains the CAR degradation (car) operon (35, 58); (ii) the backbone of pCAR1 (the region that roughly corresponds to the outside of Tn4676) shows mosaicity, i.e., it is composed of putative genes for replication that are homologous to those of other Pseudomonas sp. plasmids, as well as genes for transfer, which are similar to those of plasmids of Enterobacteriaceae (35); (iii) the putative repA gene of pCAR1 does not show similarity to the rep genes of IncP-1, IncP-9, or other replicons whose Inc groups have already been identified (35); and (iv) we have detected some pCAR1-like plasmids in other CAR-degrading bacteria (58). These findings indicate that pCAR1 is a novel type of catabolic plasmid that plays important roles in the distribution and maintenance of the car gene in the environment. However, our previous preliminary attempts to demonstrate pCAR1 transferability proved unsuccessful (58).

In this report, we elucidate some basic information on pCAR1 regarding the minimum DNA region required for replication or plasmid stability, the Inc group, and plasmid transferability in order to understand the natural distribution and maintenance mechanisms of the car genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. For the extraction of total DNA or large plasmids from bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas, strains were grown on LB medium (49) at 30°C with reciprocal shaking (300 strokes/min) for 15 h. Nitrogen plus mineral medium 4 (NMM-4) supplemented with CAR as a sole source of carbon and energy was used as a minimal medium, as described previously by Shintani et al. (57). Escherichia coli DH5α (TOYOBO, Tokyo, Japan) was used as a host strain for the preparation of plasmids pUC19 (49), pT7Blue T-vector (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan), pBBR1 vectors (32), and their derivatives. The E. coli strains were grown in 2×YT medium (49) at 37°C with reciprocal shaking (300 strokes/min). Ampicillin (Ap; 50 μg/ml), carbenicillin (Cb; 250 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (Cm; 30 μg/ml), kanamycin (Km; 50 μg/ml), gentamicin (Gm; 15 μg/ml), rifampin (Rif; 250 μg/ml), streptomycin (Sm; 450 μg/ml), or tetracycline (Tc; 12.5 μg/ml) was added to the selective medium. For plate cultures, the above media were solidified with 1.6% (wt/vol) agar.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Burkholderia sp. strain PJ310 | Polyaromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacterium isolated from soil, naturally Kmr | 68 |

| C. testosteroni IAM12419 | Type strain, naturally Kmr | IAM Culture Collection |

| E. coli K-12 | ||

| DH5α | F− Φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) deoR thi-1 supE44 λ gyrA96 relA1 | Toyobo |

| CAG18620 (ME8878) | Tn10kan inserted in the gene for carbamoyl phosphate synthase small chain; Kmr | National Institute of Genetics, Japan |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1808 | leu-9001; leu derivative of PAO1 (wild-type isolate) | 47 |

| P. putida DS1 | Dimethyl sulfoxide utilizer, naturally Cmr and Tcr | 14 |

| P. putida KT2440 | Naturally Cmr | 3 |

| P. resinovorans CA10 | CAR-degrading bacterium carrying pCAR1; naturally Cmr | 43 |

| P. resinovorans CA10dm4 | pCAR1-deficient strain; naturally Cmr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBBR1MCS-3 | Tcr; lacZα mob; compatible with IncP, IncQ, and IncW plasmids | 32 |

| pBBR1MCS-3Cm | pBBR1MCS-3 with Cmr gene in the SacI site | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-5 | Gmr; lacZα mob; compatible with IncP, IncQ, and IncW plasmids | 32 |

| pBBRparA | pBBR1MC-5 with BamHI-SpeI fragment containing parA gene | This study |

| pBBRparB | pBBR1MC-5 with BamHI-SpeI fragment containing parB gene | This study |

| pBBRparW | pBBR1MC-5 with BamHI-SpeI fragment containing parW gene | This study |

| pBBRparWAB | pBBR1MC-5 with XbaI-NdeI fragment containing parWAB genes (opposite the lac promoter) | This study |

| pBBRrepA | pBBR1MC-5 with XbaI-HindIII fragment containing repA gene | This study |

| pBluescript II KS(−) | AprlacZ; pMB9 replicon | Stratagene |

| pBSL181 | Apr Cmr minitransposon with IS50 inner and outer ends | 2 |

| pBSL202 | Apr Gmr minitransposon with IS50 inner and outer ends | 1 |

| pCAR1 | 199,035-bp CAR-degrading plasmid isolated from P. resinovorans CA10 | 35, 40 |

| pCARori004 | 6.9-kb HindIII fragment of pUCARori004 combined with Kmr gene | This study |

| pCARori004-Gm | 6.9-kb HindIII fragment of pUCARori004 combined with Gmr gene | This study |

| pCARori005 | 2.9-kb HindIII-AatII fragment of pUCARori005 combined with Kmr gene | This study |

| pCARori006 | 1-kb XbaI-AatII fragment of pUCARori006 combined with Kmr gene (nonfunctional replicon) | This study |

| pCARori008 | Fragments III and I combined with Kmr gene | This study |

| pCARΔparA | pCARΔparC with parA gene mutated | This study |

| pCARΔparB | pCARΔparC with parB gene mutated | This study |

| pCARΔparBC | repA and oriV region combined with Kmr genea | This study |

| pCARΔparC | pCARori004 with parC deletion | This study |

| pCARΔparW | pCARΔparC with parW gene mutateda | This study |

| pSJ12 | pBluescript II KS(−) with 0.7-kb SmaI fragment containing a nonpolar Gmr gene | 29 |

| pT7Blue T-vector | AprlacZ | Takara Bio |

| pTKm | pT7Blue T-vector with Kmr gene | 72 |

| pTrepAparWAB | pT7Blue T-vector with 5.7-kb HindIII-NdeI fragment of pUCARori004 | This study |

| pTCARoriVΔrepA | pT7Blue T-vector with Kmr gene and HindIII-NdeI fragment of pCARori008 with mutated repA gene | This study |

| pTCARoriV01 | pT7Blue T-vector with Kmr gene and 1,005-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment of oriV region | This study |

| pTCARoriV02 | pT7Blue T-vector with Kmr gene and 785-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment of oriV region | This study |

| pTCARoriV03 | pT7Blue T-vector with Kmr gene and 403-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment of oriV region | This study |

| pTCARoriV04 | pT7Blue T-vector with Kmr gene and 488-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment of oriV region | This study |

| pTCARoriV05 | pT7Blue T-vector with Kmr gene and 388-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment of oriV region | This study |

| pTCARoriV06 | pT7Blue T-vector with Kmr gene and 250-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment of oriV region | This study |

| pTCARoriV07 | pT7Blue T-vector with Kmr gene and 121-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment of oriV region | This study |

| pTCARoriV08 | pT7Blue T-vector with Kmr gene and 345-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment of oriV region | This study |

| pTCARoriV09 | pT7Blue T-vector with Kmr gene and 258-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment of oriV region | This study |

| pUC19 | AprlacZ; pMB9 replicon | 49 |

| pUCARori001 | pUC19 Apr Kmr, containing 17-kb SacI-PstI fragment of pCAR1 | This study |

| pUCARori002 | pUC19 Apr Kmr, containing 13.2-kb HpaI-PstI fragment of pCAR1 | This study |

| pUCARori003 | pUC19 Apr Kmr, containing 7.8-kb SacI-XbaI fragment of pCAR1 | This study |

| pUCARori004 | pUC19 Apr Kmr, containing 7-kb NheI-HindIII fragment of pCAR1 | This study |

| pUCARori004-Gm | pUCARori004 with Kmr gene replaced by Gmr gene | This study |

| pUCARori004-Tc | pUCARori004 with Kmr gene replaced by Tcr gene | This study |

| pUCARori004-TcCm | pUCARori004-Tc with Cmr gene in the SacI site | This study |

| pUCARori005 | pUC19 Apr Kmr, containing 3-kb NheI-AatII fragment of pUCARori004 | This study |

| pUCARori006 | pUC19 Apr Kmr, containing 2.7-kb HindIII-XbaI fragment of pUCARori004 | This study |

| pUCARori007 | pUC19 Apr Kmr, containing 1-kb XbaI-AatII fragment of pUCARori004 | This study |

See Fig. 1.

Standard DNA techniques.

Plasmid DNA was prepared from E. coli host cells by the alkaline lysis method (49). Plasmid DNA was extracted from Pseudomonas cells using the QIAGEN (Tokyo, Japan) Large-Construct kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (appendix A, “Special protocol for high yields of large-construct DNA without removal of genomic DNA”). Total DNA was isolated from bacterial strains as described previously (51). Restriction endonucleases (Takara Bio) and Ligation High (TOYOBO) were used according to the manufacturers' instructions. The DNA fragments were extracted from agarose gels using the EZNA gel extraction kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Doraville, GA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Other DNA manipulations were performed according to standard methods (49). The primers used for amplifying specific segments by PCR are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Hybridization analysis, electroporation, and determination of nucleotide sequences were performed as described previously (14, 40, 58).

Construction of minireplicons of pCAR1.

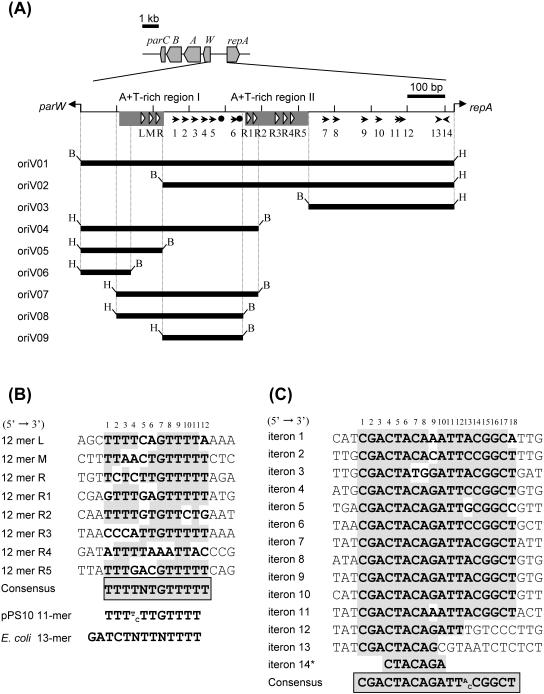

For the construction of pUCARori001, pUCARori002, pUCARori003, and pUCARori004, the 17-kb SacI-PstI, 13.2-kb HpaI-PstI, 7.8-kb SacI-XbaI, and 7-kb NheI-HindIII fragments, respectively, were cloned from pCAR1 into the corresponding sites in the pUC19 cloning site (Fig. 1; Table 1). The EcoRV-flanked Km resistance (Kmr) gene of pTKm (72) was introduced into the blunt-ended PstI site of each resulting plasmid, with the exception of pUCARori001, in which the Kmr gene was introduced directly into the blunt-ended SacI site. The 3-kb NheI-AatII, 2.7-kb HindIII-XbaI, and 1-kb XbaI-AatII fragments of pUCARori004 were subcloned into pUC19, and the Kmr gene was similarly introduced into the blunt-ended PstI site of the resulting plasmids, giving rise to pUCARori005, pUCARori006, and pUCARori007, respectively (Fig. 1; Table 1). The 6.9-kb HindIII fragment of pUCARori004, the 2.9-kb HindIII-AatII fragment of pUCARori005, and the 1-kb XbaI-AatII fragment of pUCARori006 were derived from pCAR1, and after blunting of the ends of both fragments, they were ligated with the Kmr genes, thus yielding pCARori004, pCARori005, and pCARori006, respectively (Fig. 1; Table 1). As to pCARori006, after the insert was ligated with the Kmr gene, the resultant circular DNAs were introduced directly into Pseudomonas putida DS1. We also constructed pUCARori004-Gm and pUCARori004-Tc by replacing the Kmr gene of pUCARori004 with the Gmr gene (the 0.7-kb SmaI fragment of pSJ12 [29]) and with the blunt-ended Tcr gene from pBBR1MCS-3 (32), respectively (Table 1). pUCARori004-TcCm was constructed by inserting the SacI-flanked Cmr gene fragment from pBSL181 (2) into the SacI site of pUCARori004-Tc. Similarly, pBBR1MCS-3Cm was constructed by inserting the Cmr gene into the SacI site of pBBR1MCS3 (32). The pCARori004-Gm plasmid was constructed by combining the blunt-ended 6.9-kb HindIII fragment of pUCARori004 (except for the Kmr gene) with the Gmr gene (removing a region of the pUC vector [Table 1]). For the construction of pTCARoriVΔrepA, four nucleotides were inserted into the XhoI site located in the repA gene of pCARori008 using T4 polymerase (Takara Bio), and the HindIII-NdeI fragment was ligated into the pT7Blue T-vector. For pTCARoriV01-pTCARoriV09, the fragments with artificial BamHI and HindIII sites at their termini were amplified by PCR (see Fig. 2; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material); after confirmation of the nucleotide sequences, these fragments were ligated into the pT7Blue T-vector with the Kmr gene.

FIG. 1.

Genetic map of the DNA regions (nucleotides 62422 to 79458 in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AB088420) used to construct the serial miniplasmids. Pentagons in the physical map indicate the size, location, and direction of open reading frame transcription. The oriV region (previously oriP) is represented by a white rectangle. Shaded pentagons indicate open reading frames with homologies to genes involved in plasmid (or chromosome) replication and partition. The gene names and open reading frame numbers are shown beneath the sequence; these include open reading frames 59 (similar to DNA-specific endonuclease [NP_758601]), 60 (similar to the replication terminus site-binding protein homologue [NP_758602]), 61 (similar to DNA helicase [NP_758603]), and 68 (similar to plasmid replication/partition-related protein [NP_758610]). Regions contained in the miniplasmids are indicated by solid lines. Black arrowheads below the pCARori004 diagram indicate the locations and directions of primers parF-1 (1), parR-1 (2), parF-2 (3), and parR-2 (4) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and white rectangles represent fragments I to VI, which were used for the construction of par gene-defective plasmids. Artificial restriction enzyme sites on the fragments or plasmid inserts are shown at the termini. Asterisks represent restriction enzyme sites from the vector multicloning sites. Abbreviations for restriction enzyme sites are as follows: A, AatII; Hd, HindIII; Hp, HpaI; N, NheI; Nc, NcoI; Nd, NdeI; P, PstI; Sa, SacI; Sp, SpeI; X, XbaI; Xh, XhoI. White arrowheads indicate the sites of introduced mutations.

FIG. 2.

oriV region of the IncP-7 plasmid pCAR1. (A) Genetic map of the parCBAW-oriV-repA region. A physical map of the 1,005-bp oriV region between the parW and repA initiation codons of pCAR1 is shown (nucleotides 70108 to 71112 in accession no. AB088420). Shaded rectangles, AT-rich regions; black circles, DnaA boxes. White triangles, 12-bp repeat sequences designated 12-mer L, M, R, and R1 to R5; black arrows, 18-bp repeat sequences designated iterons. The inserts of pTCARoriV01 to pTCARoriV09 are indicated by solid lines. Artificial restriction enzyme sites in the plasmid inserts are shown at the termini (B, BamHI; H, HindIII). (B) Alignment of the pCAR1 12-mer repeat sequences, the pPS10 oriV 11-mer sequence, and the E. coli oriC 13-mer sequence. (C) Alignment of the pCAR1 iterons. The asterisk indicates that the direction of the sequence is inverted. In panels B and C, conserved nucleotide and consensus sequences are shaded.

Incompatibility testing.

For incompatibility testing of pCAR1, pUCARori004-Gm was introduced by electroporation into host cells (derived from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1808) for IncP-1, IncP-2, IncP-4, IncP-5, IncP-7, IncP-9, or IncP-12 plasmids. Similarly, pUCARori004-Tc was introduced into cells that contained IncP-3, IncP-6, or IncP-13 plasmids. The electroporated cells were spread onto media that contained antibiotics selective for the minireplicon (Gm or Tc) and IncP plasmids (Table 2). The two plasmids were considered to be compatible when transformants were obtained from the selective medium within 2 days.

TABLE 2.

Incompatibility testing of pCAR1 with IncP plasmids

| Inc group | Plasmid | Selective marker(s) | Compatibility with pUCARori004 | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-1 | RP4 | Cb, Km, Tc | + | 44 |

| P-2 | Rms139 | Cb, Cm, Sm, Tc | + | 52 |

| P-3 | RIP64 | Cb, Cm, Gm | + | 27 |

| P-4 | R679 | Sm | + | 6 |

| P-5 | Rms163 | Cm, Su, Tc | + | 48, 61 |

| P-6 | Rms149 | Cb, Gm, Sm | + | 22, 24 |

| P-7 | Rms148 | Sm | − | 48 |

| P-9 | Rsu2 | Cb, Sm | + | 23 |

| P-12 | R716 | Sm | + | 5 |

| P-13 | pMG25 | Cb, Cm, Km, Gm, Sm | + | 28 |

Construction of par-defective plasmids.

Two fragments (I and II) were amplified by PCR with artificial restriction sites (Fig. 1; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). After the respective amplicons were introduced into the pT7Blue T-vector, the nucleotide sequence of each insert was confirmed by sequencing. The XbaI-NdeI (the NdeI site was derived from the multicloning site of the vector) and SpeI-NdeI fragments of the above plasmids were designated fragments I and II, respectively (Fig. 1). In addition, another four fragments (fragments III to VI [Fig. 1]) were prepared from fragment II (for fragment VI) or pUCARori004 (for fragments III to V). We amplified the HindIII-NdeI-flanked Kmr gene by PCR using pTKm (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). For the construction of pCARori008, fragments III and I were ligated and the resultant fragment was combined with the HindIII-NdeI-flanked Kmr gene (Fig. 1). For pCARΔparBC, fragments III to VI (Fig. 1) were combined with the HindIII-NdeI-flanked Kmr gene. For the construction of pCARΔparC, the 5.7-kb HindIII-NdeI fragment of pUCARori004 was combined with the HindIII-NdeI-flanked Kmr gene (Fig. 1). For the construction of par-defective plasmids with point mutations, the 5.7-kb HindIII-NdeI fragment was cloned into the pT7Blue T-vector, and the recombinant was designated pTrepAparWAB. Four nucleotides were inserted into the NcoI site in the parW gene on pTrepAparWAB (Fig. 1) by using T4 DNA polymerase (Takara Bio) to yield pTΔparW. The 5.7-kb HindIII-NdeI fragment of pTΔparW was combined with the HindIII-NdeI-flanked Kmr gene to yield pCARΔparW. Similarly, two nucleotides and four nucleotides were inserted into the ClaI and EcoRI sites of the parA and parB genes, respectively, of pTrepAparWAB to yield pTΔparA and pTΔparB, respectively (Fig. 1). Each 5.7-kb HindIII-NdeI fragment was combined with the HindIII-NdeI-flanked Kmr gene to yield pCARΔparA and pCARΔparB, respectively.

Construction of plasmids for complementation.

To construct pBBRparWAB, the 4-kb XbaI-NdeI fragment of pTrepAparWAB was cloned into the pBBR1MCS-5 vector (32) in the direction opposite the lac promoter. For the construction of pBBRparW, pBBRparA, and pBBRparB, the parW, parA, and parB genes, respectively, were amplified by PCR together with artificial ribosomal binding sites (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The nucleotide sequence of each amplicon was confirmed, and the fragments were cloned downstream of the lac promoter of the pBBR1MCS-5 vector.

RT-PCR analysis.

Total-RNA samples were isolated from P. resinovorans CA10 and P. putida HS01 using NucleoSpin RNA II (Macherey-Nagel, Sudbury, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each strain was grown in LB medium for 15 h (stationary phase). After digestion of contaminating DNA with 1 U of RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega, Madison, WI), 1 μg RNA was used as the template. Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed with the One Step RNA PCR kit (Takara Bio) under the following conditions: 60°C for 30 min; 94°C for 5 min; and 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. For the negative control, reverse transcriptase was not included in the reaction mixture.

Plasmid stability assay.

Each host strain that harbored the test plasmid was grown overnight at 30°C in LB medium that contained the relevant antibiotics. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:1,000 into fresh LB medium without antibiotics and grown at 30°C. At 24-h intervals (about every 20th generation), a sample of each culture was added at a dilution of 1:1,000 to fresh LB, and aliquots of each culture were diluted and plated onto L agar plates. The antibiotic resistance of 100 colonies on each L agar plate was checked, and the ratio of plasmid-containing antibiotic-resistant cells was calculated. For the complementation assay for the par-mutated plasmids, Gm was added to each culture to maintain the plasmids for complementation. To confirm that homologous recombination did not occur between the minireplicon of pCAR1 and the plasmid for complementation, Southern hybridization analysis with probes prepared from the repA and parA genes was performed on bacteria from each culture.

Construction of the P. resinovorans CA10 strain cured of pCAR1.

To obtain a P. resinovorans CA10 derivative that was cured of pCAR1, we constructed a parA-disrupted plasmid. The 7-kb NheI-HindIII fragment that contains repA-oriV-parWABC was cloned into pUC19 (Fig. 1). An EcoRV-flanked Kmr gene was introduced into the blunt-ended ClaI site of the insert (Fig. 1). The resultant plasmid was introduced into P. resinovorans CA10 by electroporation. Kmr colonies were selected, transferred to nonselective LB medium, and cultured overnight. Several Km-sensitive colonies were selected from this culture. This plasmid can exclude pCAR1 from strain CA10 when cultured with Km because both plasmids belong to the same Inc group. Because the miniplasmid itself was unstable in nonselective media, we were able to obtain a CA10 derivative that was cured of pCAR1. To confirm that the strain had lost pCAR1, Southern hybridization analysis was performed with probes prepared from the repA gene. The resultant strain was designated P. resinovorans CA10dm4.

Mating techniques and isolation of transconjugants.

Before the mating experiment, spontaneous Rif- or Km-resistant derivatives of Burkholderia sp. strain PJ310, Comamonas testosteroni IAM12419, E. coli K-12 CAG18620, P. putida KT2440, and P. resinovorans CA10dm4 were selected. A mini-Tn5 transposon with the Gmr gene of pBSL202 was introduced into the above strains by electroporation. Combined resistance to Rif and Gm for strains KT2440 and CA10dm4, or to Km and Gm for strains PJ310 and IAM12419, was used for counterselection against the donor strain (except for E. coli K-12 CAG18620, which was selected with Kmr alone), and the ability to grow on CAR was used as the selection marker for the transconjugant. Filter matings were performed on cellulose nitrate filters (pore size, 0.45 μm), as described previously (58). The number of transconjugants was determined by counting the colonies on the selective medium 5 days after mating. To confirm that each transconjugant was derived from the respective recipients and contained pCAR1, Southern hybridization analysis with the car probe prepared from the carbazole degradation genes (carAaAaBaBbCAcAd [carAa genes were duplicated]) of strain CA10 (58) and determination of the 16S rRNA gene nucleotide sequences were performed on the transconjugants obtained.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The repA-oriV region is sufficient for the replication of pCAR1.

Previously, we reported that pCAR1 was predicted to carry a single gene (repA) that encodes a replication initiator protein as well as an origin of replication (oriV, formerly designated oriP [35]) region, although the RepA function has not been proven (35). To determine the minimal DNA fragment involved in the replication of pCAR1, we cloned the region encompassing repA and oriV and their flanking genes into pUC19 vectors (designated pUCARori001 to pUCARori007) (Fig. 1) and tested their abilities to replicate in P. putida DS1, which was originally isolated as a dimethyl sulfide-utilizing bacterium (14). After electrotransformation of DS1 with these plasmids, transformants that carried pUCARori001, pUCARori002, pUCARori004, or pUCARori005 were obtained (transformation efficiencies, approximately 102 colonies per μg of DNA). However, no transformants were obtained for pUCARori003, pUCARori006, or pUCARori007 (efficiencies, <1 colony per 10 μg of DNA). To exclude the possibility that some DNA region of the pUC vector affected replication, pCARori004, pCARori005, and pCARori006 were constructed by removing the pUC vector regions from the above plasmids, and their abilities to replicate in DS1 were tested. To investigate whether pCAR1 could replicate in E. coli, these three plasmids were introduced into E. coli strains DH5α and JM109. DS1 transformants were obtained for pCARori004 and pCARori005 (at about 102 colonies per μg of DNA) but not for pCARori006 (<1 colony per 10 μg of DNA), while no E. coli transformants were obtained for any of these plasmids (<1 colony per 10 μg of DNA). To confirm that pCARori004 and pCARori005 were maintained in the DS1 transformants as plasmids and not as chromosomal insertions, plasmid DNA was extracted from each transformant. Plasmid DNA was isolated from each of the transformants (data not shown). This indicates that an approximately 2.7-kb DNA region that contains repA and the putative oriV is sufficient for the replication of pCAR1 in P. putida DS1, while this region is not sufficient for pCAR1 replication in E. coli.

The minimal region of oriV exists in a 345-bp DNA region on pCAR1.

To determine the minimal region of oriV on pCAR1, we tested whether RepA could act in trans for the oriV region in P. putida DS1. The repA gene was supplied in trans from pBBRrepA, which expresses repA under the control of the lac promoter. For the test plasmids, pTCARoriVΔrepA and pTCARoriV01 were constructed, which carry the putative pCAR1 oriV and repA disrupted by internal or complete deletions, respectively (Fig. 1 and 2). Although these two plasmids were not able to replicate in P. putida DS1 (data not shown), they could replicate efficiently in strains that harbored pBBRrepA (about 102 colonies per μg of DNA for both plasmids). Kanamycin-resistant transformants of P. putida DS1 (pBBRrepA) appeared on plates in either the presence or the absence of 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (data not shown). Thus, it appears that repA can be supplied in trans in P. putida DS1. In the case of pMT2 (IncP-9), it has been reported that although the oriV-rep region is not sufficient for replication in E. coli, an increased supply of rep allows plasmid replication (55). We investigated whether mini-pCAR1 (pCARori005) could replicate in E. coli in the presence of an increased supply of repA, which was expressed from pBBRrepA with (0.1 mM) or without IPTG in E. coli JM109. No transformants were detected (<1 colony per 10 μg of DNA), which suggests that pCAR1 is unable to replicate in E. coli even with an increased supply of repA. In addition, the pTCARoriV02-to-pTCARoriV09 series of plasmids, which carry various fragments of the oriV-flanking region, were constructed (Fig. 2A), and the ability to be established in DS1 with pBBRrepA was tested. Only pTCARoriV04, pTCARoriV07, and pTCARoriV08 were established in this strain (approximately 102 colonies per μg of DNA [Fig. 2A]). This suggests that the oriV of pCAR1 is located within the insert of pTCARoriV08, which represents a 345-bp DNA region in P. putida DS1 (Fig. 2A).

The repA gene product of pCAR1 shows high overall lengthwise identity with pL6.5 (98%) (GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession no. CAB60146), pND6-1 (98%) (34), and pWW53 (95%) (31; H. Yano and M. Tsuda, unpublished data) and also shows low-level identity with pECB2 (43%), pPS10 (39%), and pRO1600 (31%). The RepA protein of the narrow-host-range plasmid pPS10 isolated from Pseudomonas savastanoi has been investigated in detail both enzymatically and biochemically (reviewed in reference 19). As with many plasmids, the RepA protein of pPS10 binds to repeat sequences, called iterons, in the oriV region (19). AT-rich or GC-rich regions have also been found, and two copies of an 11-mer repeat sequence (5′-TTT(T/C)TTGTTTT-3′) exist in an AT-rich region (38). A DnaA box, which is the binding site of the DnaA protein produced by the host strain, is also found in the oriV region of pPS10 (19). In the case of pCAR1, two AT-rich regions (regions I and II) and three copies of a 12-bp repeat sequence were found in AT-rich region I and another five copies were located in region II (Fig. 2A and B). These sequences are similar to the three copies of a 13-mer repeat sequence (5′-GATCTNTTNTTTT-3′) found in the oriC gene of E. coli (56) (Fig. 2B). We have named the above repeat sequences of pCAR1 the 12-mers L, M, and R and the 12-mers R1 to R5 (Fig. 2A and B). Two putative DnaA box sequences (5′-TTATCCACA-3′ and 5′-TTGTGCACG-3′) have been identified, and the former sequence is identical to that found in oriC of E. coli (4) (Fig. 2A). We also found 14 copies of 18-mer repeat sequences from the oriV region (Fig. 2A and C). Considering the relative locations of the AT-rich regions, DnaA boxes, and 18-mer repeats, these 18-mer repeats are predicted to be the iterons of pCAR1 (Fig. 2A and C), although their nucleotide sequences have no similarity to known iteron sequences (33). We showed that repA and the above region that contains oriV can be separated in P. putida DS1 and that a ∼345-bp DNA region on pCAR1 is needed in cis for plasmid replication (Fig. 2A). These findings suggest the importance of the 12-mers L, M, R, R1, and R2, iterons 1 to 6, and the two DnaA boxes for pCAR1 replication.

pCAR1 belongs to the IncP-7 group.

To determine the incompatibility group of pCAR1, we performed incompatibility testing with the IncP plasmids listed in Table 2. The pUCARori004-Gm plasmid, which was constructed to replace the Kmr gene of pUCARori004 with a Gmr gene, was used as a minireplicon of pCAR1. On selective media with dual antibiotics, it was impossible to obtain a transformant that carried both Rms148 (IncP-7) and pUCARori004-Gm (transformation efficiency, <1 colony per 10 μg of DNA), whereas other IncP group plasmids were compatible with the test plasmids (about 102 colonies per μg of DNA) (Table 2). We detected a transformant with pUCARori004-Gm on selective medium with Gm but without Sm, although the transformation efficiency was relatively low (about 1 colony per 5 μg of DNA). The transformants lost resistance to Sm, indicating the loss of Rms148 from the host strain. To transfer Rms148 into the pCAR1 host, filter mating was performed. For the pCAR1 host, Gm- and Rif-resistant P. putida strain KT2440 that harbored pCAR1 was used. Streptomycin-resistant transconjugants were obtained, although the conjugation frequency was very low (about 10−7 cells/donor cell). The transconjugants did not grow on NMM-4 with CAR, indicating that pCAR1 was lost from its host. These results suggest that pCAR1 belongs to the IncP-7 group. To corroborate this, Southern hybridization analysis was performed under low-stringency conditions (hybridization and washing steps at 60°C) with the total DNA of the host strains of each IncP plasmid (including IncP-8 plasmid FP2 [45]) by using a probe prepared from the repA gene of pCAR1. A single signal was detected with the DNA of the host strain that carried Rms148 (data not shown). This indicates that pCAR1 belongs to the IncP-7 group of plasmids. As described by Thomas and Haines (63), archetypes of only three Pseudomonas plasmid Inc groups have been completely sequenced: IncP-1 (RP4, R751, pADP-1, pB2, and pB3 [25]; pB4 [25]; pB8 [53]; pB10 and pEST4011 [67]; pJP4, pUO1, and pTB11 [62]), IncP-4 (RSF1010, pDN1, and pIE1130), and IncP-9 (pWW0 and pDTG1), and very recently, the complete sequence of the archetypal IncP-6 plasmid Rms149 was determined (22). Thus, pCAR1 is the first IncP-7 plasmid for which the entire nucleotide sequence has been determined.

Each of pL6.5, pND6-1, and pWW53 carried a repA gene and putative oriV region highly homologous with those of pCAR1. Thus, it is possible that these three plasmids may belong to the IncP-7 group, as described by Dennis (8), and that the putative oriV sequences are characteristic of IncP-7 plasmids.

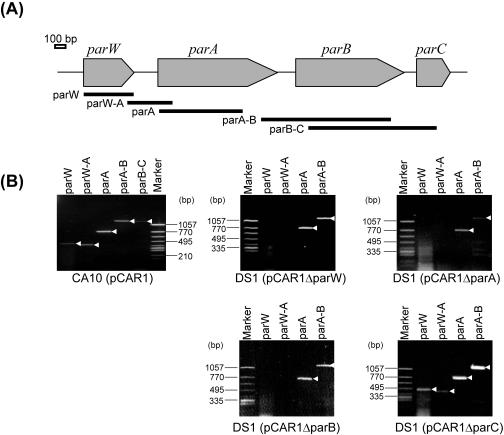

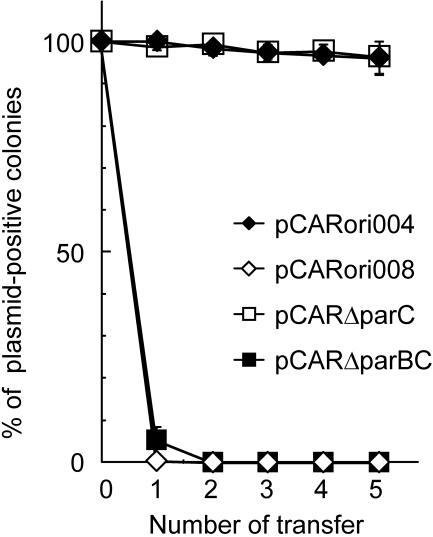

DNA regions of parWABC are involved in the stable maintenance of pCAR1.

We located the parWABC genes, which are predicted to be involved in the partitioning of the plasmid (35), upstream of the repA gene of pCAR1 and in opposite orientations. To investigate whether these genes were expressed in the host strains, RT-PCR was performed with total RNA extracted from cultures of P. resinovorans CA10 by using the primers shown in Fig. 3A. Specific RT-PCR products for each gene and the corresponding internal regions were detected (Fig. 3B). This suggests that parWABC is expressed at the transcriptional level and is transcribed as a single transcriptional unit. Comparisons of the plasmid maintenance properties in nonselective (LB) cultures of P. putida DS1 were performed with pCARori004 (includes the repA-oriV-parWABC region) and pCARori008 (contains only the repA gene and oriV region [Fig. 1]); pCARori004 was stably maintained in DS1 after five transfers, whereas pCARori008 was rapidly lost from the host (Fig. 4). This indicates that the parWABC genes are involved in the stability of pCAR1. This fact could explain our previous findings; we obtained strains CA10dm1 and CA10dm3, which had lost some of the plasmid DNA but retained the DNA region that contains the repA, oriV, and parWABC genes in all strains, even after 22 successive cultures on nonselective media (66).

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR analysis for the detection of par gene expression (mRNA transcripts). (A) Genetic map of the parWABC gene cluster. Bold solid lines indicate the locations and sizes of putative PCR products for each primer set: parW (475 bp), parW-A (430 bp), parA (790 bp), parA-B (1,310 bp), and parB-C (1,075 bp). (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis of RT-PCR products using primer sets parW, parW-A, parA, parA-B, and parB-C with CA10(pCAR1) and DS1 with each mutated plasmid. White arrowheads indicate amplified fragments. No products were detected under the condition without reverse transcriptase (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Role of the par genes in the stability of pCAR1. The stabilities of the test plasmids pCARori004 (containing repA-oriV-parWABC) (black diamonds), pCARori008 (containing repA-oriV) (white diamonds), pCARΔparC (containing repA-oriV-parWAB) (white squares), and pCARΔparBC (containing repA-oriV-parWA) (black squares) in P. putida DS1 were compared as the relative percentages of Kmr transformants at each transfer into nonselective (LB) medium. Each assay was performed at least three times.

parWAB is sufficient for the stable maintenance of pCAR1.

To determine which of the genes of the parWABC cluster participate in the stability of pCAR1, we constructed mini-pCAR1 with the par genes deleted, i.e., pCARΔparBC and pCARΔparC (Fig. 1), and compared their maintenance properties (numbers of colonies carrying each plasmid) to those of mini-pCAR1 that carried either parWABC (pCARori004) or no par genes (pCARori008). The results are shown in Fig. 4 and Table 3. The pCARΔparC plasmid was stably maintained in P. putida DS1 without Km after five transfers, while pCARΔparBC was rapidly lost after 24 h of cultivation, which indicates that the parC gene is not necessary for pCAR1 stability. In addition, we constructed various minireplicons that had small deletion mutations in the three par genes, designated pCARΔparW, pCARΔparA, and pCARΔparB (Fig. 1), and compared their stabilities (Table 3). We found that each plasmid with a mutated par gene was rapidly lost from strain DS1 even after 24 h of cultivation (Table 3). We also performed complementation assays, and the stability of each mutated plasmid was assessed. Before the complementation assay, we confirmed the transcription of each par gene on plasmids for complementation in P. putida DS1 by RT-PCR (data not shown). The coexistence of pBBRparW or pBBRparA slightly improved the survival rate of pCARΔparW or pCARΔparA, which was retained at about 14% in strain DS1 after 24 h of cultivation, as shown in Table 3. When pBBRparB coexisted with pCARΔparB, plasmid stability was not improved (Table 3). In contrast, when pBBRparWAB coexisted with pCARΔparW, -ΔparA, or -ΔparB, stability after 24 h of cultivation was improved (approximately 68%, 62%, or 60%, respectively), although these plasmids were unstable compared to pCARΔparC (Table 3). The coexistence of the empty vector pBBR1MCS-5 with each mutated plasmid did not recover the mutated plasmids stability (data not shown). The possibility that each plasmid used in the complementation assay had a destabilizing effect on the mini-pCAR1 replicon was excluded by confirming the stable maintenance of pCARΔparC in combination with pBBRparW, -parA, or -parB (data not shown). Using RT-PCR, we ascertained par gene transcription in each host that carried a mutated plasmid. As a result, although the parA and parB transcripts were detected in cells that contained each mutated plasmid, we were unable to detect the parW transcript (Fig. 3B). This result implies that the ParW protein is required for the stable maintenance of the mini-pCAR1 replicon. In summary, our results suggest that the stability of pCAR1 depends on the ParW, ParA, and ParB proteins but not on the parC region.

TABLE 3.

Mutational and complementation analysis of pCAR1 par genes

| Plasmid(s)a | % of plasmid retainedb after:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 24-h cultivation on nonselective medium | Fifth transfer to fresh nonselective medium | |

| pCARori004 | 100 ± 0 | 96 ± 4 |

| pCARori008 | <0.3 | <0.3 |

| pCARori008 + pBBRparWAB | 57 ± 14 | <0.3 |

| pCARΔparC | 99 ± 0.6 | 96 ± 4 |

| pCARΔparBC | 5 ± 3 | <0.3 |

| pCARΔparW | 2 ± 2 | <0.3 |

| pCARΔparW + pBBRparW | 14 ± 6 | <0.3 |

| pCARΔparW + pBBRparWAB | 68 ± 14 | <0.3 |

| pCARΔparA | 1 ± 1 | <0.3 |

| pCARΔparA + pBBRparA | 14 ± 7 | <0.3 |

| pCARΔparA + pBBRparWAB | 62 ± 9 | <0.3 |

| pCARΔparB | <0.3 | <0.3 |

| pCARΔparB + pBBRparB | <0.3 | <0.3 |

| pCARΔparB + pBBRparWAB | 60 ± 11 | <0.3 |

Plus signs signify the coexistence of the mutated plasmids with each plasmid used for complementation.

The stability of each plasmid is shown as the percentage of plasmid-positive colonies after 24 h of culture or after 120 h in culture with five transfers into nonselective medium. Each assay was performed at least three times.

Most partition systems that have been characterized to date consist of two plasmid-encoded proteins and a DNA site (par site) for binding the proteins (16, 17). The par site often contains one or more inverted repeats as recognition elements for DNA-binding proteins and serves as the loading site for the rest of the segregation machinery (16, 17). From the amino acid alignment, it appears that pCAR1 has a Walker-type ATPase (ParA) and a DNA-binding protein (ParB) that resemble those of other plasmids (data not shown). Indeed, plasmids with the parA and parB mutant genotype were unstable in P. putida DS1, which indicates that these two genes function as predicted. Although we cannot yet explain why the transcription of parW on each mutated plasmid was undetectable (Fig. 3B), the ParW protein is clearly important for the stable maintenance of pCAR1 (Table 3). However, its function has not yet been established. ParW does not show any significant homology with functional proteins in a BLAST search. From hydrophobicity analysis using the SOSUI program (http://sosui.proteome.bio.tuat.ac.jp), ParW was predicted to be a membrane protein with a transmembrane region at the N terminus. Similar predictions were obtained using other programs, such as TMPRED (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html) and PSORT (http://psort.ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp). Therefore, it is possible that ParW functions as a membrane protein in the partition of pCAR1.

The mutated parW, parA, and parB genes were partially complemented by pBBRparWAB (Table 3). In contrast, the stability of the parW- or parA-defective plasmid was only slightly improved by pBBRparW or -parA, and pBBRparB was not able to improve the stability of parB-defective plasmids (Table 3), although the expression of each par gene was confirmed by RT-PCR. Similarly, it has been reported that abnormal amounts and ratios of the Par proteins disrupt the proper maintenance of the P1 plasmid (15, 16, 17). In the case of pCAR1, it is possible that the Par proteins supplied from pBBRparW, -parA, or -parB were not present in the correct amounts and ratios, since each of the par genes in the above plasmids was located downstream of the lac promoter, which is known to be expressed constitutively in Pseudomonas spp. (46).

Like the oriV region of pCAR1, the 3.3-kb par operon of pCAR1 was conserved in other (putative) IncP-7 plasmids, i.e., pND6-1, pWW53, and pL6.5. Interestingly, potential binding sites (such as inverted repeats) for the ParB protein were not found upstream of the parA gene or downstream of the parB gene, as is the case in well-characterized plasmids, such as P1 and R1 (16, 17). However, the coexistence of pBBRparWAB and pCARori008 (which carries no par genes) improved stability after 24 h of cultivation (about 57% [Table 3]). This suggests that a nucleotide sequence recognized by the Par system of pCAR1 may be located in the insert of oCARori008, i.e., upstream of the parW gene. To elucidate the function of the Par proteins and the location of the recognition site for the Par system of pCAR1, a more detailed analysis is needed.

pCAR1 is a self-transmissible plasmid.

The conjugative transfer of pCAR1 was examined using Burkholderia sp. strain PJ310, C. testosteroni IAM12419, E. coli K-12 CAG18620 (ME8878), P. resinovorans CA10dm4, and P. putida KT2440 as recipients in mating experiments. The transfer of pCAR1 from CA10 to strains CA10dm4 and KT2440 was detected at frequencies of 3 × 10−1 and 3 × 10−3 per donor cell, respectively. These results suggest that pCAR1 is a self-transmissible plasmid. However, we were unable to detect pCAR1 transfer to strains PJ310, IAM12419, and CAG18620 (frequencies, <10−7 per donor cell). To investigate whether pCAR1 could replicate or become established in Burkholderia sp. strain PJ310 (Cm sensitive) or C. testosteroni IAM12419 (Tc sensitive), we constructed pCARori004-TcCm and introduced it into these recipient strains by electroporation. No transformants were obtained with pCARor004-CmTc, although the broad-host-range plasmid pBBR1MCS-3Cm could be introduced into these strains (data not shown). This result indicates that the host range for conjugation of pCAR1 into non-Pseudomonas hosts is determined primarily by ability to replicate. In our previous experiments, the conjugative transfer of pCAR1 from P. resinovorans CA10 to P. putida DS1 and Pseudomonas fluorescens IAM12022RG was not detectable (58). In contrast, we could detect replication and establishment of a plasmid that had the same repA and oriV as pCAR1 in other Pseudomonas recipients, such as strains DS1 and IAM12022 (57). Thus, lack of replicative ability is not sufficient to explain why pCAR1 is unable to transfer to these Pseudomonas recipients from P. resinovorans CA10. Recently, it has been reported that the plasmid donor affects the host range of broad-host-range plasmids in an activated sludge (18). One possibility is that the conjugative frequency may be altered by host regulation of transfer genes in donor strains. Another possibility is that the restriction-modification systems of the donor and recipient strains may affect the acquisition of foreign DNAs (64).

Southern hybridization analysis found that Rms148 also carries the tra/trh genes (data not shown), which suggests that not only the replication and partition system, but also the transfer system, may be conserved in IncP-7 plasmids. This suggests that pCAR1 may be an archetypal plasmid of the IncP-7 group, and more detailed investigations of its replication, partition, and conjugative transfer are important for understanding the general characteristics of IncP-7 plasmids.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Y. Iyobe of the Gumma University School of Medicine for providing the series of IncP plasmids used for incompatibility testing.

This work was supported by the program Promotion of Basic Research Activity for Innovative Bioscience (PROBRAIN) of Japan and by a grant-in-aid (Hazardous Chemicals) from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan (HC-05-2325-1).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexeyev, M. F., I. N. Shokolenko, and T. P. Croughan. 1995. New mini-Tn5 derivatives for insertion mutagenesis and genetic engineering in gram-negative bacteria. Can. J. Microbiol. 41:1053-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexeyev, M. F., I. N. Shokolenko, and T. P. Croughan. 1995. Improved antibiotic-resistance gene cassettes and omega elements for Escherichia coli vector construction and in vitro deletion/insertion mutagenesis. Gene 160:59-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagdasarian, M., R. Lurz, B. Ruckert, F. C. H. Franklin, M. M. Bagdasarian, J. Frey, and K. N. Timmis. 1981. Specific-purpose plasmid cloning vectors. II. Broad host range, high copy number, RSF1010-derived vectors, and a host-vector system for gene cloning in Pseudomonas. Gene 16:237-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bramhill, D., and A. Kornberg. 1988. Duplex opening by DnaA protein at novel sequences in initiation of replication at the origin of the E. coli chromosome. Cell 52:743-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryan, L. E., S. D. Semaka, H. M. van den Elzen, J. E. Kinnear, and R. L. S. Whitehouse. 1973. Characteristics of R931 and other Pseudomonas aeruginosa R factors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 3:625-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryan, L. E., H. M. van den Elzen, and J. T. Tseng. 1972. Transferable drug resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1:22-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakrabarty, A. M. 1972. Genetic basis of the biodegradation of salicylate in Pseudomonas. J. Bacteriol. 112:815-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennis, J. J. 2005. The evolution of IncP catabolic plasmid. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 16:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dennis, J. J., and G. J. Zylstra. 2004. Complete sequence and genetic organization of pDTG1, the 83 kilobase naphthalene degradation plasmid from Pseudomonas putida strain NCIB 9816-4. J. Mol. Biol. 341:753-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Souza, M. L., L. P. Wackett, and M. J. Sadowsky. 1998. The atzABC genes encoding atrazine catabolism are located on a self-transmissible plasmid in Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2323-2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Don, R. H., and J. M. Pemberton. 1981. Properties of six pesticide degradation plasmids isolated from Alcaligenes paradoxus and Alcaligenes eutrophus. J. Bacteriol. 145:681-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Don, R. H., A. J. Weightman, H. J. Knackmuss, and K. N. Timmis. 1985. Transposon mutagenesis and cloning analysis of the pathways for degradation of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 3-chlorobenzoate in Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP134(pJP4). J. Bacteriol. 161:85-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn, N. W., and I. C. Gunsalus. 1973. Transmissible plasmid coding early enzymes of naphthalene oxidation in Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 114:974-979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Endoh, T., K. Kasuga, M. Horinouchi, T. Yoshida, H. Habe, H. Nojiri, and T. Omori. 2003. Characterization and identification of genes essential for dimethyl sulfide utilization in Pseudomonas putida strain DS1. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 62:83-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funnell, B. E. 1988. Mini-P1 plasmid partitioning: excess ParB protein destabilizes plasmids containing the centromere parS. J. Bacteriol. 170:954-960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Funnell, B. E., and R. A. Slavcev. 2004. Partition systems of bacterial plasmids, p. 81-103. In E. Funnell and G. J. Philips (ed.), Plasmid biology. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 17.Funnell, B. E. 2005. Partition-mediated plasmid pairing. Plasmid 53:119-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gelder, L. E., F. P. J. Vandecasteele, C. J. Brown, L. J. Forney, and E. M. Top. 2005. Plasmid donor affects host range of promiscuous IncP-1b plasmid pB10 in an activated-sludge microbial community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5309-5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giraldo, R., and M. E. Fernández-Tresguerres. 2004. Twenty years of the pPS10 replicon: insights on the molecular mechanism for the activation of DNA replication in iteron-containing bacterial plasmids. Plasmid 52:69-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greated, A., L. Lambersten, P. A. Williams, and C. M. Thomas. 2002. Complete sequence of the IncP-9 TOL plasmid pWW0 from Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. 4:856-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Habe, H., J.-S. Chung, J.-H. Lee, K. Kasuga, T. Yoshida, H. Nojiri, and T. Omori. 2001. Degradation of chlorinated dibenzofurans and dibenzo-p-dioxins by two types of bacteria having angular dioxygenases with different features. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3610-3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haines, A. S., K. Jones, M. Cheung, and C. M. Thomas. 2005. The IncP-6 plasmid Rms149 consists of a small mobilizable backbone with multiple large insertions. J. Bacteriol. 187:4728-4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedges, R. W., and A. E. Jacob. 1975. Mobilization of plasmid-borne drug resistance determinants for transfer from Pseudomonas aeruginosa to Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 140:69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hedges, R. W., and G. A. Jacoby. 1980. Compatibility and molecular properties of plasmid Rms149 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli. Plasmid 3:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heuer, H., R. Szczepanowski, S. Schneiker, A. Puhler, and E. M. Top. 2004. The complete sequences of plasmids pB2 and pB3 provide evidence for a recent ancestor of the IncP-1β group without any accessory genes. Microbiology 150:3591-3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill, K. E., and A. J. Weightman. 2003. Horizontal transfer of dehalogenase genes on IncP1β plasmids during bacterial adaptation to degrade α-halocarboxylic acids. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 45:273-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacoby, G. A. 1974. Properties of R plasmids determining gentamicin resistance by acetylation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 6:239-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacoby, G. A. 1986. Resistance plasmids of Pseudomonas, p. 265-293. In J. R. Sokatch (ed.), The bacteria. Academic Press, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 29.Jain, S., and D. E. Ohman. 1998. Deletion of algK in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa blocks alginate polymer formation and results in uronic acid secretion. J. Bacteriol. 180:634-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawasaki, H., H. Yahara, and K. Tonomura. 1981. Isolation and characterization of plasmid pUO1 mediating dehalogenation of haloacetate and mercury resistance in Moraxella sp. B. Agric. Biol. Chem. 45:1477-1481. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keil, H., S. Keil, R. W. Pickup, and P. A. Williams. 1985. Evolutionary conservation of genes coding for meta pathway enzymes within TOL plasmids pWW0 and pWW53. J. Bacteriol. 164:887-895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovach, M. E., P. H. Elzer, D. S. Hill, G. T. Robertson, M. A. Farris, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krüger, R., S. A. Rakowski, and M. Filutowicz. 2004. Participating elements in the replication of iteron-containing plasmids, p. 25-45. In E. Funnell and G. J. Philips (ed.), Plasmid biology. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 34.Li, W., J. Shi, X. Wang, Y. Han, W. Tong, L. Ma, B. Liu, and B. Cai. 2004. Complete nucleotide sequence and organization of the naphthalene catabolic plasmid pND6-1 from Pseudomonas sp. strain ND6. Gene 336:231-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maeda, K., H. Nojiri, M. Shintani, T. Yoshida, H. Habe, and T. Omori. 2003. Complete nucleotide sequence of carbazole/dioxin-degrading plasmid pCAR1 in Pseudomonas resinovorans strain CA10 indicates its mosaicity and the presence of large catabolic transposon Tn4676. J. Mol. Biol. 326:21-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez, B., J. Tomkins, L. P. Wackett, R. Wing, and M. J. Sadowsky. 2001. Complete nucleotide sequence and organization of the atrazine catabolic plasmid pADP-1 from Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP. J. Bacteriol. 183:5684-5697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakazawa, T., and T. Yokota. 1973. Benzoate metabolism in Pseudomonas putida (arvilla) mt-2: demonstration of two benzoate pathways. J. Bacteriol. 115:262-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nieto, C., R. Girado, M. E. Fernández-Tresguerres, and R. Diaz. 1992. Genetic and functional analysis of the basic replicon of pPS10, a plasmid specific for Pseudomonas isolated from Pseudomonas syringae pathovar savastanoi. J. Mol. Biol. 223:415-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nojiri, H., and T. Omori. 2002. Molecular bases of aerobic bacterial degradation of dioxins: involvement of angular dioxygenation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 61:2001-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nojiri, H., H. Sekiguchi, K. Maeda, M. Urata, S. Nakai, T. Yoshida, H. Habe, and T. Omori. 2001. Genetic characterization and evolutionary implications of car gene cluster in the carbazole degrader Pseudomonas sp. strain CA10. J. Bacteriol. 183:3663-3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nojiri, H., M. Shintani, and T. Omori. 2004. Divergence of mobile genetic elements involved in the distribution of xenobiotic-catabolic capacity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 64:154-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ogawa, N., A. M. Chakrabarty, and O. Zaborina. 2004. Degradative plasmids, p. 341-376. In E. Funnell and G. J. Philips (ed.), Plasmid biology. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 43.Ouchiyama, N., Y. Zhang, T. Omori, and T. Kodama. 1993. Biodegradation of carbazole by Pseudomonas spp. CA06 and CA10. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 57:455-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pansegrau, W., E. Lanka, P. T. Barth, D. H. Figurski, D. G. Guiney, D. Haas, D. R. Helsinki, H. Schwab, V. A. Stanisich, and C. M. Thomas. 1994. Complete nucleotide sequence of Birmingham IncPα plasmids. Compilation and comparative analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 239:623-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pemberton, J. M., and A. J. Clark. 1973. Detection and characterization of plasmids in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains PAO. J. Bacteriol. 114:424-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rist, M., and M. A. Kertesz. 1998. Construction of improved plasmid vectors for promoter characterization in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 169:179-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Royle, P. L., H. Matsumoto, and B. W. Holloway. 1981. Genetic circularity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 145:145-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sagai, H., K. Hasuda, S. Iyobe, L. E. Bryan, B. W. Holloway, and S. Mitsuhashi. 1976. Classification of R plasmids by incompatibility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 10:573-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 50.Sato, S., J.-W. Nam, K. Kasuga, H. Nojiri, H. Yamane, and T. Omori. 1997. Identification and characterization of genes encoding carbazole 1,9a-dioxygenase in Pseudomonas sp. strain CA10. J. Bacteriol. 179:4850-4858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sato, S., N. Ouchiyama, T. Kimura, H. Nojiri, H. Yamane, and T. Omori. 1997. Cloning of genes involved in carbazole degradation of Pseudomonas sp. strain CA10: nucleotide sequences of genes and characterization of meta-cleavage enzymes and hydrolase. J. Bacteriol. 179:4841-4849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sawada, Y., S. Yaginuma, M. Tai, S. Iyobe, and S. Mitsuhashi. 1976. Plasmid-mediated penicillin beta-lactamases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 9:55-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schluter, A., H. Heuer, R. Szczepanowski, S. M. Poler, S. Schneiker, A. Puhler, and E. M. Top. 2005. Plasmid pB8 is closely related to the prototype IncP-1β plasmid R751 but transfers poorly to Escherichia coli and carries a new transposon encoding a small multidrug resistance efflux protein. Plasmid 54:135-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Serdar, C. M., and D. T. Gibson. 1989. Isolation and characterization of altered plasmids in mutant strains of Pseudomonas putida NCIB9816. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 164:764-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sevastsyanovich, Y. R., M. A. Titok, R. Krasowiak, L. E. H. Bingle, and C. M. Thomas. 2005. Ability of IncP-9 plasmid pM3 to replicate in Escherichia coli is dependent on both rep and par functions. Mol. Microbiol. 57:819-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shaper, S., and W. Messer. 1995. Interaction of the initiator protein DnaA of Escherichia coli with its DNA target. J. Biol. Chem. 270:17622-17626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shintani, M., H. Habe, M. Tsuda, T. Omori, H. Yamane, and H. Nojiri. 2005. Recipient range of IncP-7 conjugative plasmid pCAR2 from Pseudomonas putida HS01 is broader than from other Pseudomonas strains. Biotechnol. Lett. 27:1847-1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shintani, M., T. Yoshida, H. Habe, T. Omori, and H. Nojiri. 2005. Large plasmid pCAR2 and class II transposon Tn4676 are functional mobile genetic elements to distribute the carbazole/dioxin-degradative car gene cluster in different bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 67:370-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sota, M., H. Kawasaki, and M. Tsuda. 2003. Structure of haloacetate-catabolic IncP-1β plasmid pUO1 and genetic mobility of its residing haloacetate-catabolic transposon. J. Bacteriol. 185:6741-6745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stuart-Keil, K. G., A. M. Hohnstock, K. P. Drees, J. B. Herrick, and E. L. Madsen. 1998. Plasmids responsible for horizontal transfer of naphthalene catabolism genes between bacteria at a coal tar-contaminated site are homologous to pDTG1 from Pseudomonas putida NCIB 9816-4. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3633-3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Summers, A. O., and G. A. Jacoby. 1978. Plasmid-determined resistance to boron and chromium compounds in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 13:637-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tennstedt, T., R. Szczepanowski, I. Krahn, A. Puhler, and A. Schluter. 2005. Sequence of the 68,869 bp IncP-1α plasmid pTB11 from a waste-water treatment plant reveals a highly conserved backbone, a Tn402-like integron and other transposable elements. Plasmid 53:218-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thomas, C. M., and A. S. Haines. 2004. Plasmids of the genus Pseudomonas, p. 197-231. In J.-L. Ramos (ed.), Pseudomonas. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 64.Thomas, C. M., and K. M. Nielsen. 2005. Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:711-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Trefault, N., R. de la Iglesia, A. M. Molina, M. Manzano, T. Ledger, D. Pérez-Pantoja, M. A. Sánchez, M. Stuardo, and B. González. 2004. Genetic organization of the catabolic plasmid pJP4 from Ralstonia eutropha JMP134(pJP4) reveals mechanisms of adaptation to chloroaromatic pollutants and evolution of specialized chloroaromatic degradation pathways. Environ. Microbiol. 6:655-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Urata, M., M. Miyakoshi, S. Kai, K. Maeda, H. Habe, T. Omori, H. Yamane, and H. Nojiri. 2004. Transcriptional regulation of the ant operon, encoding two-component anthranilate 1,2-dioxygenase, on the carbazole-degradative plasmid pCAR1 of Pseudomonas resinovorans strain CA10. J. Bacteriol. 186:6815-6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vedler, E., M. Vahter, and A. Heinaru. 2004. The completely sequenced plasmid pEST4011 contains a novel IncP1 backbone and a catabolic transposon harbouring tfd genes for 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid degradation. J. Bacteriol. 186:7161-7174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Widada, J., H. Nojiri, K. Kasuga, T. Yoshida, H. Habe, and T. Omori. 2002. Molecular detection and diversity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria isolated from geographically diverse sites. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 58:202-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Williams, P. A., R. M. Jones, and G. Zylstra. 2004. Genomics of catabolic plasmids, p. 165-195. In J.-L. Ramos (ed.), Pseudomonas. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 70.Williams, P. A., and K. Murray. 1974. Metabolism of benzoate and the methylbenzoates by Pseudomonas putida (arvilla) mt-2: evidence for the existence of a TOL plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 120:416-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wong, C. L., and N. W. Dunn. 1974. Transmissible plasmid coding for the degradation of benzoate and m-toluene in Pseudomonas arvilla mt-2. Genet. Res. 23:227-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yoshida, T., Y. Ayabe, M. Yasunaga, Y. Usami, H. Habe, H. Nojiri, and T. Omori. 2003. Genes involved in the synthesis of the exopolysaccharide methanolan by the obligate methylotroph Methylobacillus sp. strain 12S. Microbiology 149:431-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.