Abstract

A gene encoding an exo-β-1,3-galactanase from Clostridium thermocellum, Ct1,3Gal43A, was isolated. The sequence has similarity with an exo-β-1,3-galactanase of Phanerochaete chrysosporium (Pc1,3Gal43A). The gene encodes a modular protein consisting of an N-terminal glycoside hydrolase family 43 (GH43) module, a family 13 carbohydrate-binding module (CBM13), and a C-terminal dockerin domain. The gene corresponding to the GH43 module was expressed in Escherichia coli, and the gene product was characterized. The recombinant enzyme shows optimal activity at pH 6.0 and 50°C and catalyzes hydrolysis only of β-1,3-linked galactosyl oligosaccharides and polysaccharides. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of the hydrolysis products demonstrated that the enzyme produces galactose from β-1,3-galactan in an exo-acting manner. When the enzyme acted on arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs), the enzyme produced oligosaccharides together with galactose, suggesting that the enzyme is able to accommodate a β-1,6-linked galactosyl side chain. The substrate specificity of the enzyme is very similar to that of Pc1,3Gal43A, suggesting that the enzyme is an exo-β-1,3-galactanase. Affinity gel electrophoresis of the C-terminal CBM13 did not show any affinity for polysaccharides, including β-1,3-galactan. However, frontal affinity chromatography for the CBM13 indicated that the CBM13 specifically interacts with oligosaccharides containing a β-1,3-galactobiose, β-1,4-galactosyl glucose, or β-1,4-galactosyl N-acetylglucosaminide moiety at the nonreducing end. Interestingly, CBM13 in the C terminus of Ct1,3Gal43A appeared to interfere with the enzyme activity toward β-1,3-galactan and α-l-arabinofuranosidase-treated AGP.

Clostridium thermocellum is an anaerobic, thermophilic, and cellulolytic bacterium. C. thermocellum produces the most efficient enzyme complex for the degradation of polysaccharides in biomass, a large extracellular cellulase system called the cellulosome (1, 10). The cellulosome is an extremely complicated protein complex consisting of nearly 20 different catalytic subunits ranging in size from about 40 to 210 kDa, with a total molecular mass of millions. The principal component of the cellulosome is a scaffoldin subunit that integrates the various catalytic subunits into the complex through interactions between its repetitive cohesin domains and complementary dockerin domains (1, 10). The scaffoldin also frequently includes a carbohydrate-binding module (CBM) through which the complex usually recognizes and binds to the substrate. Some of the components may be involved in cellulose hydrolysis. Others may be involved in degradation of other plant cell wall polysaccharides (1, 46). Many of the known cellulosomes include different types and mixed compositions of hemicellulases in addition to cellulases.

Arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs) are an abundant and heterogeneous class of highly glycosylated hydroxyproline (Hyp)-rich glycoproteins found in the extracellular matrix associated with the higher plant plasma membrane and cell wall (7, 11, 13, 36). Recent characterization of genes encoding different AGPs from several species has given rise to the current distinction between classical and nonclassical AGPs (5, 9, 29). Classical AGPs contain a domain responsible for attaching the protein to a glycosylphosphatidylinositol membrane anchor (3, 34, 38, 45). In contrast, nonclassical AGPs lack this glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor signal, making them soluble components of the extracellular matrix, and often contain Asn- or Hyp-rich domains (13, 27, 35). The carbohydrate moieties of AGPs have a common structure consisting of β-1,3-galactosyl backbones (sugars in the present study are d series unless otherwise designated) that is substituted at O-6 by side chains of β-1,6-galactosyl residues. l-Arabinose and lesser amounts of other auxiliary sugars, such as glucuronic acid, l-rhamnose, and l-fucose, are attached to the side chains, usually at nonreducing termini (21).

Molecular and biochemical evidence has indicated that AGPs have specific functions during root formation (41, 43), promotion of somatic embryogenesis (23, 40, 42), and attraction of pollen tubes in the style (6, 33, 44). However, since a large number of putative protein cores exist and because of the complex structures of carbohydrate moieties, it has been difficult to differentiate one species of AGP from another in plant tissues. This, in turn, has made it difficult to assign specific roles to the individual AGPs. In spite of the significant physiological interest in AGPs, there has been very little research done on glycoside hydrolases that cleave their sugar moieties. We believe that it is important to study such enzymes, as hydrolytic enzymes specific to particular sugar residues and type of glycosidic linkage will provide useful tools for the structural analysis of the sugar moieties of AGPs.

Glycoside hydrolases have been classified in the CAZy database (http://www.cazy.org/CAZY/) (14). The classification system of the CAZy database is based on amino acid sequence similarities and reflects the structural features of the enzymes. Since there is a direct relationship between sequence and folding similarities, the members of one family most likely share the same architecture. Glycoside hydrolysis occurs via two major mechanisms, giving rise to either an overall retention or an inversion of anomeric configuration; enzymes in the same family catalyze by the same hydrolysis mechanism (8). The sequence-based classification of families of enzymes provides useful clues to their function but not to their substrate specificity.

The galactanases which can hydrolyze β-1,3- or β-1,6-galactosyl linkages are useful tools, as the enzymes hydrolyze the carbohydrate moieties of AGPs. Unfortunately, due to the lack of research, not many such enzymes are known. Recently for the first time, we cloned two such enzymes, the endo-β-1,6-galactanase belonging to glycoside hydrolase family 5 (GH5) from Trichoderma viride (no EC number) and the exo-β-1,3-galactanase belonging to GH43 from Phanerochaete chrysosporium (EC 3.2.1.145) (18, 22). The exo-β-1,3-galactanase is an especially powerful tool to analyze AGP since it is able to accommodate branched side chains when the enzyme hydrolyzes main-chain β-1,3-linkage of the carbohydrate moiety of AGPs.

In spite of their interest, exo-β-1,3-galactanases have been previously identified only in fungi (18, 32, 39). When the amino acid sequence of exo-β-1,3-galactanase from P. chrysosporium (Pc1,3Gal43A) was compared with sequences in the protein and nucleic acid database BLAST (on the website of the National Center for Biotechnology Information, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/), Pc1,3Gal43A showed 34% similarity with the hypothetical protein of Clostridium thermocellum ATCC 27405 (GenBank accession number ZP_00312459.1). To demonstrate that the exo-β-1,3-galactanases are not exclusive to fungi, we cloned the gene of the hypothetical protein of C. thermocellum and investigated the properties of the recombinant protein.

Here, for the first time, we report an exo-β-1,3-galactanase from a bacterium. In this paper, we demonstrate that exo-β-1,3-galactanases are one of the components of cellulosomes and that the enzymes are widely distributed in nature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Substrates.

p-Nitrophenyl glycosides (PNP glycosides) (such as PNP-β-Galp, PNP-α-Galp, PNP-β-Glcp, PNP-β-l-Arap, PNP-β-Xylp, PNP-β-Manp, and PNP-β-Fucp), larch arabinogalactan, laminarin, birchwood xylan, oat spelt xylan, β-1,3-galactosyl l-arabinofuranoside, and β-1,3-galactosyl glucosaminide were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Debranched arabinan and pectic galactan from lupine were from Megazyme International, Ltd. (Wicklow, Ireland). β-1,3-Galactosyl galactosaminide was from BioCarb (Lund, Sweden). Gum arabic was from Nacalai Tesque, Inc. (Kyoto, Japan). Carboxymethyl curdlan (CM-curdlan) was from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Arabinan, β-1,3-galactan, and β-1,3-β-1,6-galactan from Prototheca zopfii, native and α-l-arabinofuranosidase-treated AGPs from radish, and β-1,3-, β-1,4-, and β-1,6-galacto-oligosaccharides, 4-O-MeGlcA-β-1,6-Gal [4MeGlcA(β1-6)Gal], and 4-O-MeGlcA-β-1,6-Gal-β-1,6-Gal [4MeGlcA(β1-6)Gal2] were prepared as previously described (18). Methyl β-glycoside of β-1,3-galactotetraose and -pentaose were kind gifts from P. Kováč of the National Institutes of Health, NIDDKD (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD). β-1,3-Xylan was a kind gift from Y. Kitamura of the National Food Research Institute (Tsukuba, Japan).

Expression of recombinant Ct1,3Gal43A.

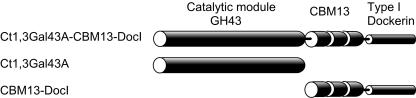

For the expression of the full-length enzyme (Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13-DocI) (where Ct1,3Gal43A is the C. thermocellum exo-β-1,3-galactanase and CBM13 is the family 13 CBM of Ct1,3Gal43A), the catalytic module (Ct1,3Gal43A), or the CBM (CBM13-DocI), the pET expression system (Novagen, Madison, WI) was used. The PCRs were performed by using the following sets of primers: F1 (forward primer, 5′-CAT ATG GCA GAA GGG GTT ATA GTC AAC-3′) and R1 (reverse primer, 5′-CTC GAG TTA CAA ATC CAC TTC CAT AAG-3′) for Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13-DocI; F1 and R2 (reverse primer, 5′-CTC GAG AGT GTC AGG TAT GTA TTC AGA-3′) for Ct1,3Gal43A; and F2 (forward primer, 5′-AAG CTT ACA CGC TAC AAA CTG GTA AAC-3′) and R1 for CBM13-DocI (Fig. 1). The amplified fragment was subcloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI), and the complete nucleotide sequences of the genes were determined with an ABI PRISM 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Each gene was individually inserted into the pET30 or pET27 vector with a restriction enzyme site of NdeI-XhoI or HindIII-XhoI (underlined).

FIG. 1.

Domain structure of Ct1,3Gal43A. GH43, glycoside hydrolase family 43; CBM13, carbohydrate-binding module family 13; DocI, type I dockerin domain.

The resultant plasmids (pET30/Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13-DocI; pET30/Ct1,3Gal43A; and pET27/CBM13-DocI) were transformed into the Escherichia coli strain Rosetta (Novagen, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The transfected cells were cultured, and expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 24 h at 23°C. The cells were harvested and then were resuspended in 5 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) and sonicated for 5 min. After removal of insoluble material by centrifugation, the supernatants were used as crude enzymes. The crude enzyme of Ct1,3Gal43A was purified with a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany) column (5 by 50 mm). In the case of Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13-DocI, the crude enzyme was loaded on a lactosyl-Sepharose column (5 by 50 mm), and the bound enzyme was eluted with a 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 200 mM lactose (19). The eluted enzyme was detected by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (25), and the relevant fractions were pooled and dialyzed against deionized water. The final preparation thus obtained was used as purified enzyme.

Characterization of recombinant Ct1,3Gal43A.

Activity of exo-β-1,3-galactanase was determined by the Somogyi-Nelson method (37). The reaction mixture consisted of 20 μl of McIlvaine buffer (0.2 M Na2HPO4, 0.1 M citric acid), pH 6.0, and 25 ml of 1% (wt/vol) β-1,3-galactan. After 5 min of preincubation at 37°C, 5 μl of enzyme was added to the solution and the reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 min. The reaction was terminated by heating the solution at 100°C for 5 min (standard condition). One unit of enzyme activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that released 1 μmol of galactose/min. Enzyme concentration was determined by using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagent kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. SDS-PAGE was carried out using a 12% polyacrylamide gel, and the protein was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250. The effects of pH on the activity and stability of Ct1,3Gal43A were investigated according to a method previously described (18). The N-terminal amino acid sequences of recombinant enzymes were determined with a model HP G105A protein sequence system. Affinity electrophoresis was performed as previously described (18). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry was performed with a KOMPACT MALDI IV tDE system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Recombinant Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13-DocI dissolved in 0.5 μl of water was crystallized by adding 0.5 μl of matrix solution (containing 1% [wt/vol] sinapinic acid and 0.1% [vol/vol] trifluoroacetic acid) and 0.5 μl of 1% (wt/vol) NaCl, which was then allowed to dry. For the mass calibration, bovine serum albumin (molecular mass, 66.431 kDa) was used.

Substrate specificity.

The substrate specificity of Ct1,3Gal43A was determined using various PNP glycosides as substrates. The enzyme was incubated with 1 mM PNP glycoside in McIlvaine buffer, pH 6.0, at 37°C for 10 min, and the reactions were terminated by adding Na2CO3 to the final concentration of 0.1 M. The amount of PNP released was then determined by measuring absorbance at 400 nm with an extinction coefficient of 19,608 M−1 cm−1.

The substrate specificity toward polysaccharides and oligosaccharides was determined at 37°C in McIlvaine buffer, pH 6.0, with 0.5% (wt/vol) polysaccharide or 5 mM of oligosaccharide as the substrate and 0.16 μM of enzyme. After incubation for the appropriate reaction time, the amount of hydrolysis was quantified by the Somogyi-Nelson method (37).

The catalytic efficiency of the enzyme against β-1,3-galacto-oligosaccharides was investigated as previously reported (18). Briefly, the enzyme (1.8 nM) was incubated with substrate (10 μM) in McIlvaine buffer, pH 6.0, at 37°C. At regular time intervals, 100-μl aliquots were taken and heated at 100°C for 5 min to terminate the reaction. The substrate and the primary reaction products were then quantified by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with a pulsed amperometric detection system (HPAEC-PAD) as previously reported (18, 28).

The hydrolysis products of β-1,3-galactan or α-l-arabinofuranosidase-treated AGP from radish root were determined by HPAEC-PAD. The enzyme reactions were performed at 37°C in McIlvaine buffer, pH 6.0, containing 0.5% (wt/vol) substrate and 0.2 μM of enzyme and terminated by heating the solution at 100°C for 5 min. The products were analyzed by comparing their retention time by HPAEC to that of a standard sample.

FAC.

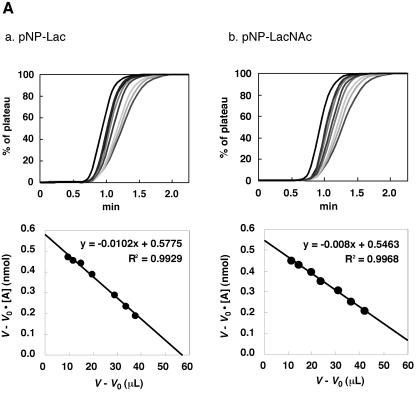

The affinity of CBM13 of Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13 for a range of oligosaccharides was determined by frontal affinity chromatography (FAC) using Ct1,3Gal43A as a control, according to a method described previously (16-18, 31). Pyridylaminated (PA) oligosaccharides, containing a terminal galactose residue, used as substrates are shown in Fig. 4B. PA-Lac (Galβ1-4Glc), PA-Gb3 (Galα1-4Galβ1-4Glc), PA-GA1 (Galβ1-3GalNAcβ1-4Galβ1-4Glc), PA-LNT (Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc), PA-LNnT (Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc), PA-Galili penta (Galα1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc), and PA-rhamnose were purchased from TaKaRa (Kyoto, Japan). Nonlabeled oligolactosamines LN1 (Galβ1-4GlcNAc), LN2 (Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAc), and LN3 (Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAc) and milk oligosaccharides βGalLac (Galβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc) and βGal2Lac (Galβ1-3Galβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc) were gifts from K.-I. Yoshida (Seikagaku Co., Japan) and T. Urashima (Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Japan), respectively. The nonlabeled glycans were pyridylaminated with GlycoTAG (TaKaRa Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan) prior to use. PNP-Lac or PNP-LacNAc (Galβ1-4GlcNAc), purchased from Sigma, was used for determination of the total amount of immobilized recombinant enzyme in the column (see Fig. 4A), according to a method described previously (16-18, 31).

FIG.4.

FAC analysis of CtCBM13 moiety. (A) Elution profiles used to determine the affinity of CtCBM13 moiety for (a) Lac or (b) LacNAc (top panels) and Eadie-Hofstee plots of the FAC data (bottom panels). (B) Structures of oligosaccharides used for FAC. (C) Elution profiles of PA oligosaccharides after application to immobilized CtCBM13 moiety.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Modular structure of exo-β-1,3-galactanase from C. thermocellum.

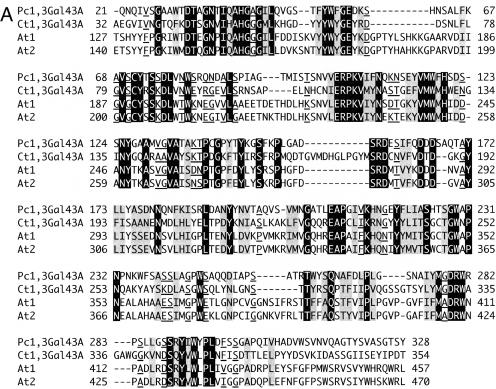

Using the amino acid sequence of Pc1,3Gal43A, a gene of C. thermocellum (GenBank accession number ZP_00312459.1) encoding a putative protein (annotated as a β-xylosidase in the NCBI database) was found. The DNA sequence was 1,716 bp long and putatively encodes a 571-amino-acid protein. The deduced amino acid sequence was compared with sequences in the protein database by using BLAST (on the website of the National Center for Biotechnology Information, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). The sequence, Ct1,3Gal43A, resembled the following sequences, in order of decreasing similarity: hypothetical protein SAV2109 from Streptomyces avermitilis MA-4680 (46% identity and 60% similarity, GenBank accession number BAC69820.1); hypothetical protein BT3685 from Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron VPI-5482 (37% identity and 54% similarity, AAO78790.1); hypothetical protein BT2112 from Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron VPI-5482 (36% identity and 53% similarity, AAO77219.1); β-glucanase precursor from Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron VPI-5482 (38% identity and 53% similarity, AA78788.1); hypothetical protein P0471B04.23 from Oryza sativa (40% identity and 55% similarity, BAC07339.1); hypothetical protein T16K5.230 from Arabidopsis thaliana (38% identity and 53% similarity, AAM20364.1); and hypothetical protein AT5g67540/K9I9_10 from Arabidopsis thaliana (39% identity and 55% similarity, BAB08462.1).

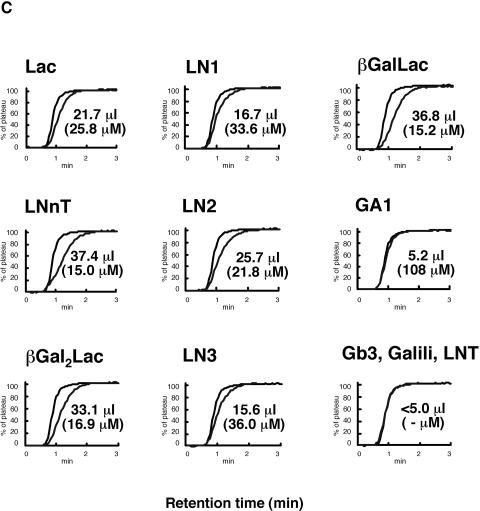

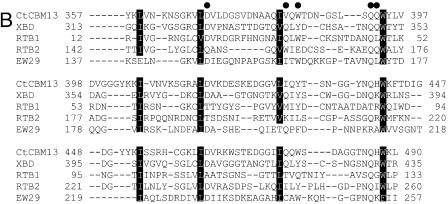

Further analysis revealed that residues 77 to 267 of Ct1,3Gal43A showed sequence similarity to GH43 enzymes, while residues 357 to 490 showed similarity with CBM13 (Fig. 2A and B). The sequence at the N terminus is a signal sequence, and the C-terminal sequence is a dockerin domain, a cohesin binding region which normally mediates association with the cellulosome (Fig. 2C). The latter suggests that Ct1,3Gal43A is a cellulosome component (1, 46). Since AGPs might be the adhesive matrix between cellulose microfibrils and/or other matrix polysaccharides, the β-1,3-galactanases could be involved in exposing cellulose from the intricacy of the plant cell wall matrix for the parent cellulolytic bacterium.

FIG.2.

Partial sequence alignment of Ct1,3Gal43A. (A) Sequence alignment of catalytic amino acids of P. chrysosporium Pc1,3Gal43A (GenBank accession number AB200390), C. thermocellum Ct1,3Gal43A (ZP_00312459.1), Arabidopsis thaliana At1 (CAB66926.1), and A. thaliana At2 (BAB08462.1). The alignment was performed with ClustalW. Identical amino acid residues are enclosed in black boxes. Conserved and semiconserved amino acid residues are in gray boxes and underlined, respectively. (B) Sequence alignment of selected CBM13s. CtCBM13, carbohydrate-binding module from exo-β-1,3-galactanase from C. thermocellum; XBD, xylan-binding domain from xylanase 10A from Streptomyces olivaceoviridis (Protein Data Bank entry 1XYF_A); RTB1 and RTB2, domains 1 and 2 of ricin toxin B chain from Ricinus communis (Protein Data Bank entry 2AAI_B); EW29, galactose-binding lectin from the earthworm Lumbricus terrestris (GenBank accession number BAA36394) (15). • indicates residues involved in substrate binding in RTB. The amino acid residues corresponding to the forming hydrophobic core of RTB are enclosed in black boxes. (C) Sequence alignment of selected type I dockerins. CtDocI is the type I dockerin module from exo-β-1,3-galactanase from C. thermocellum. Others are PDB entries 1CLC (20), 1DAV_A (26), 1DAQ_A (26), and 1OHZ_B (4).

Expression and characterization of recombinant exo-β-1,3-galactanase.

According to the domain structure, three plasmids, designated pET30/Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13-DocI, pET30/Ct1,3Gal43A, and pET27/CBM13-DocI, were constructed and were expressed in E. coli (Fig. 1). While CBM13-DocI could not be expressed as soluble protein, approximately 90 mg/liter of Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13-DocI and 380 mg/liter of Ct1,3Gal43A were successfully expressed. Purified Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13-DocI and Ct1,3Gal43A could be resolved as single bands by SDS-PAGE when visualized by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (data not shown). The molecular mass of Ct1,3Gal43A as estimated from SDS-PAGE was found to be 38 kDa, while the molecular mass of Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13-DocI was determined to be 51 kDa, which is somewhat smaller than the predicted molecular mass (62 kDa). The N-terminal amino acid sequence of Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13-DocI was AEGVI, which corresponded to the N terminus of the mature enzyme. When matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry was used to determine the accurate molecular mass of Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13-DocI, the molecular ion [M+H]+, 52,823.0 was obtained. This corresponded to the mass of the residues from 32 to 504, suggesting that the protein included both the catalytic module (the residues from 32 to 354) and CBM13 (the residues from 357 to 490). Furthermore, Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13-DocI could be purified by lactosyl-Sepharose affinity chromatography between the interaction of CBM13 and lactose, indicating that the CBM13 moiety was properly folded. Therefore, the purified Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13-DocI most likely has a C-terminal dockerin domain deletion. The purified Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13 was used to perform further experiments.

When Ct1,3Gal43A was incubated with β-1,3-galactan, exo-β-1,3-galactanase activity was detected and the specific activity was 21.3 U/mg. The enzyme achieved maximal activity at pH 6.0, and the activity on this substrate was stable between pH 3.0 and 10.0. The enzyme achieved maximal activity at 50°C, and more than 80% activity was retained after incubation at 55°C and pH 6.0 for 1 h.

Substrate specificity of Ct1,3Gal43A.

Ct1,3Gal43A was tested for the activities reported for the GH43 family, using the following substrates: β-1,3-galactan, gum arabic, larch arabinogalactan, debranched arabinan, arabinan, soluble oat spelt xylan, soluble birchwood xylan, and PNP glycosides. The enzyme showed significant activity only toward β-1,3-galactan and did not show any additional activities previously reported for GH43 (data not shown). Subsequently, activity of the enzyme towards other polysaccharides which have structures similar to that of β-1,3-galactan was tested (Table 1). The enzyme did not hydrolyze β-1,4-linked galactose-containing polysaccharides, such as pectic galactan and α-l-arabinofuranosidase-treated pectic galactan from lupine, and also did not hydrolyze laminarin, CM-curdlan, or β-1,3-xylan, suggesting that the enzyme acts only on a β-1,3-linked galactan chain. This is also apparent from the substrate specificities for oligosaccharides. The enzyme hydrolyzed β-1,3-linked galacto-oligosaccharides but did not hydrolyze β-1,4-linked and β-1,6-linked galacto-oligosaccharide (Table 2). Ct1,3Gal43A also could not hydrolyze the β-1,3-galactosyl linkage of β-1,3-galactosyl galactosaminide, β-1,3-galactosyl glucosaminide, or β-1,3-galactosyl l-arabinofuranoside (Table 2). These data suggest that Ct1,3Gal43A cleaves only β-1,3-linkage between two galactosyl residues, concluding that Ct1,3Gal43A is an exo-β-1,3-galactanase.

TABLE 1.

Substrate specificity of Ct1,3Gal43A toward polysaccharidesa

| Substrate | Activity (μM galactose/min) | Relative activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| β-1,3-Galactan | 21 ± 0 | 100 |

| Pectic galactan (β-1,4-galactan) | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| Lupine galactan (β-1,4-galactan) | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| CM-curdlan (β-1,3-glucan) | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| β-1,3-Xylan | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| Laminarin (β-1,3-β-1,6-glucan) | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| β-1,3-β-1,6-Galactan | 0.65 ± 0.08 | 3.1 |

| Native leaf AGP from radish | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| α-l-Arabinofuranosidase-treated root AGP from radish | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 9.3 |

The final concentrations of substrates were 0.5% (wt/vol). Results are means± standard errors of the means from a linear regression. Relative activity is expressed as a percentage, where activity toward β-1,3-galactan is taken as 100%.

TABLE 2.

Substrate specificity of Ct1,3Gal43A toward galacto-oligosaccharidesa

| Substrate | Concn | Activity (μM galactose/min) | Relative activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-1,3-Galactan | 5 mg/ml | 21 ± 0 | 100 |

| β-1,3-Galactobiose | 5 mM | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 31 |

| β-1,3-Galactotriose | 5 mM | 25 ± 2 | 119 |

| β-1,4-Galactobiose | 5 mM | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| β-1,4-Galactotriose | 5 mM | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| β-1,4-Galactotetraose | 5 mM | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| β-1,6-Galactobiose | 5 mM | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| β-1,6-Galactotriose | 5 mM | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| β-1,6-Galactotetraose | 5 mM | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| Gal-β-1,3-GalNAc | 5 mM | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| Gal-β-1,3-GlcNAc | 5 mM | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| Gal-β-1,3-Ara | 5 mM | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0 |

Results are means ± standard errors of the means from a linear regression. Relative activity is expressed as a percentage, where activity toward β-1,3-galactan is taken as 100%. Abbreviations: Gal-β-1,3-GalNAc, β-1,3-galactosyl galactosaminide; Gal-β-1,3-GlcNAc, β-1,3-galactosyl glucosaminide; Gal-β-1,3-Ara, β-1,3-galactosyl l-arabinofuranoside.

The catalytic efficiency of Ct1,3Gal43A against β-1,3-galacto-oligosaccharides with different degrees of polymerization (dp) was determined (Table 3). The catalytic efficiency was slightly increased from galactobiose (dp2) to galactotetraose (dp4). The enzyme displayed maximal activity against galactotetraose (dp4), indicating that the number of major subsites of Ct1,3Gal43A is four.

TABLE 3.

Rates of β-1,3-linked galacto-oligosaccharide hydrolysis by Ct1,3Gal43Aa

| Degree of polymerization of β-1,3-galacto-oligosaccharides | kcat/Km (min−1 mM−1) |

|---|---|

| 2 | 263 ± 18 |

| 3 | 1,183 ± 416 |

| 4 | 3,314 ± 330 |

| 5 | 2,085 ± 80 |

Results are means ± standard errors of the means from a linear regression.

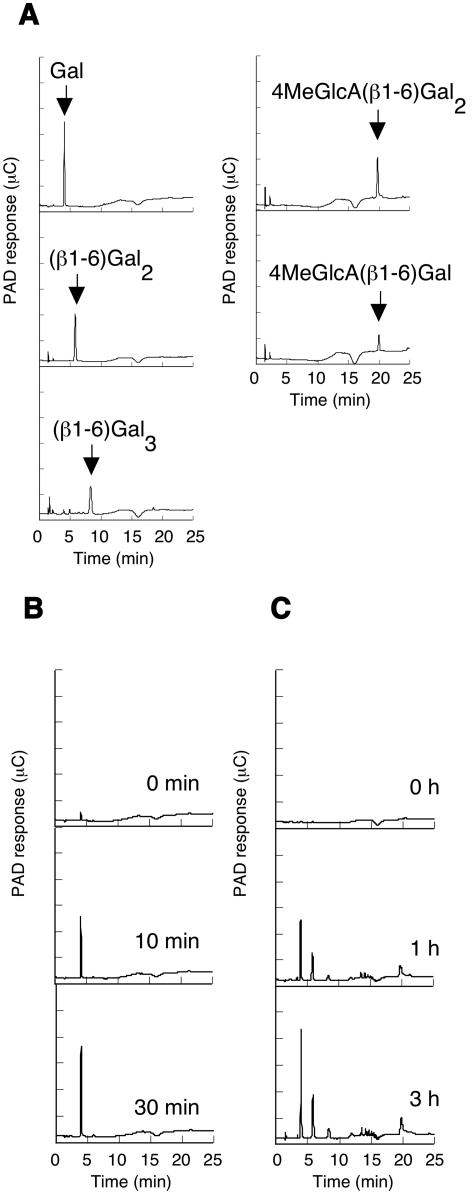

The hydrolysis products of Ct1,3Gal43A for β-1,3-galactan or radish AGP were analyzed by HPAEC-PAD (Fig. 3). When the enzyme hydrolyzed β-1,3-galactan, only galactose was produced, suggesting that Ct1,3Gal43A releases galactose in an exo-acting manner (Fig. 3B). In the case of the hydrolysis of α-l-arabinofuranosidase-treated AGP, the activity was lower than that for β-1,3-galactan. However, peaks corresponding to β-1,6-galactobiose, β-1,6-linked galactotriose, 4MeGlcA(β1-6)Gal, and 4MeGlcA(β1-6)Gal2 were detected in addition to galactose (Fig. 3C). The data suggest that the enzyme is able to accommodate the β-1,6-linked galactosyl side chains in AGPs, a property similar to that of Pc1,3Gal43A. Therefore, we concluded that Ct1,3Gal43A is an exo-β-1,3-galactanase.

FIG. 3.

HPAEC-PAD analysis of hydrolysis products of β-1,3-galactan or radish AGP generated by Ct1,3Gal43A. Ct1,3Gal43A (0.2 μM) was incubated with 0.5% (wt/vol) substrate in McIlvaine buffer, pH 6.0, at 37°C. At regular intervals, reaction products were analyzed by means of HPAEC-PAD as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Standards. (B) β-1,3-Galactan as a substrate. (C) α-l-Arabinofuranosidase-treated AGP from radish root as a substrate.

CBM13.

CBM13 consists of three similar repeated peptides of about 40 residues, referred to as subdomains α, β, and γ, and these three units assemble around the pseudo threefold axis, forming a globular structure. This combination of three subdomains results in a fold similar to the β-trefoil fold. This fold is shared by plant galactose-binding lectins, ricin B chain, and abrin B chain, in which two sets of domains with a triple repeated sequence are arranged in tandem (12). Comparison with the ricin/lactose complex showed that most of the residues involved in lactose binding in ricin are strictly conserved among all three subdomains of CtCBM13, indicating that CtCBM13 could bind to galactose. However, there are no reports of CBM13 binding to β-1,3-galactan.

Thus far, several studies of the characteristics of CtCBM13 have been conducted. To clarify the binding specificity of CtCBM13, Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13 was analyzed by affinity gel electrophoresis and FAC by using Ct1,3Gal43A as a control. When Ct1,3Gal43A or Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13 was applied on gels which contained polysaccharides, such as hydroxyethylcellulose, soluble birchwood xylan, laminarin, gum arabic, gum arabic after twice-repeated Smith degradation, gum arabic after thrice-repeated Smith degradation (β-1,3-galactan), larch arabinogalactan, potato galactan, or β-1,3-xylan, no significant affinity for these substrates was observed (data not shown). However, the result of FAC using Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13 indicated that CtCBM13 binds to several oligosaccharides, including βGalLac and βGal2Lac, which contained β-1,3-linked galactosyl residues at the nonreducing end, and Lac, LNnT, LN1, LN2, and LN3, which possessed β-1,4-linked galactosyl residues at the nonreducing end (Fig. 4), whereas Ct1,3Gal43A did not show affinity for any substrate (data not shown). The affinity of CtCBM13 for βGalLac, which has an additional β-1,3-Gal at the nonreducing end of lactose, was significantly higher than that for lactose (Fig. 4C). The Kd values for βGalLac and βGal2Lac (both containing β-1,3-linked galactosyl residues) were 15.2 μM and 16.9 μM, respectively. The Kd values for LN3, LN2, and LNnT (substrates containing β-1,4-linked galactosyl residues) were 36 μM, 21.8 μM, and 15.0 μM, respectively. CtCBM13 showed higher affinity for the oligosaccharide consisting of two LacNAc units (LN2) than for LacNAc. In contrast, the affinity of CtCBM13 for three LacNAc units (LN3) was lower than that for LacNAc. Moreover, CtCBM13 bound more strongly to LNnT than to LN2.

The sequence alignment of selected CBM13s with CtCBM13 is shown in Fig. 2B. The aromatic residues involved in substrate binding are conserved in all three subdomains of CtCBM13, suggesting that CtCBM13 has three binding pockets. Interestingly, some residues in the xylan-binding domain (XBD) (12, 24), the earthworm Lumbricus terrestris 29-kDa lectin (EW29) (15), and the ricin toxin B chain (RTB) (30), which were shown to form hydrogen bonds with the substrate, were not conserved in CtCBM13. The variation in these residues may cause the difference in substrate specificity in CBM13. The affinity of CtCBM13 for lactose (25.8 μM) was much higher than that of the xylan-binding module from Streptomyces lividans (SlCBM13, 1.0 mM), and it was the same order as for the other lectins (2). The results of FAC analysis indicated that CtCBM13 binds to oligosaccharides containing β-1,3-linked or β-1,4-linked galactosyl residues. The affinity of CtCBM13 for βGalLac was almost the same as that for βGal2Lac (Fig. 4C), suggesting that CtCBM13 recognizes β-1,3-galactobiose (not triose) at the nonreducing end.

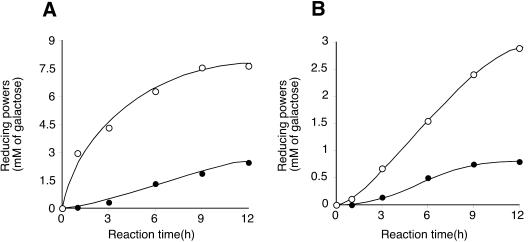

When the exo-1,3-galactanase activities of the two variants with or without CtCBM13 were compared, CtCBM13 appeared to interfere with the exo-β-1,3-galactanase activity on β-1,3-galactan and α-l-arabinofuranosidase-treated AGP (Fig. 5). This could be explained by the fact that CtCBM13 recognizes the β-1,3-galactobiose at the nonreducing end and thereby blocks the enzyme from accessing its substrate. However, further analysis to examine the competition between the CtCBM13 and the catalytic domain could not be performed because it was not possible to express CtCBM13 only.

FIG. 5.

Effect of CtCBM13 on the hydrolysis rate of Ct1,3Gal43A. Enzyme (0.2 μM) was incubated with 0.5% (wt/vol) substrate in McIlvaine buffer, pH 6.0, at 37°C. At regular intervals, the amounts of hydrolysis products were determined by the Somogyi-Nelson method. Symbols: ○, Ct1,3Gal43A; •, Ct1,3Gal43A-CBM13. (A) β-1,3-Galactan. (B) α-l-Arabinofuranosidase-treated AGP from radish root.

Conclusion.

Because exo-β-1,3-galactanases had so far been identified only in fungi, we were interested in seeing if exo-β-1,3-galactanases are also common in other branches of life. In this study, we report for the first time an exo-β-1,3-galactanase from a bacterium, Ct1,3Gal43A. Comparing the amino acid sequence of Pc1,3Gal43A to available databases indicates that there are similar sequences not only in bacteria but also in plants (Fig. 2A, At1 and At2). Indeed, the At1 and At2 proteins demonstrated exo-β-1,3-galactanase activity when they were expressed in Pichia pastoris (S. Kaneko et al., unpublished data). The exo-β-1,3-galactanases seem to be distributed in the fungal, bacterial, and plant kingdoms. We believe that further studies of exo-β-1,3-galactanase will help us to determine the individual structure of AGPs and that this in turn will help us to define the physiological function of each AGP type in the future.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to P. Kováč (National Institutes of Health, NIDDKD) for supplying the oligosaccharide substrates. We are also grateful to Y. Kitamura (National Food Research Institute) for supplying β-1,3-xylan. We wish to thank S. Nakamura and R. Yabe for FAC analyses and S. Numao and L. Lo Leggio for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayer, E. A., J. P. Belaich, Y. Shoham, and R. Lamed. 2004. The cellulosomes: multienzyme machines for degradation of plant cell wall polysaccharides. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58:521-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boraston, A. B., P. Tomme, E. A. Amandoron, and D. G. Kilburn. 2000. A novel mechanism of xylan binding by a lectin-like module from Streptomyces lividans xylanase 10A. Biochem. J. 350:933-941. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borner, G. H., D. J. Sherrier, T. J. Stevens, I. T. Arkin, and P. Dupree. 2002. Prediction of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins in Arabidopsis. A genomic analysis. Plant Physiol. 129:486-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carvalho, A. L., F. M. Dias, J. A. Prates, T. Nagy, H. J. Gilbert, G. J. Davies, L. M. Ferreira, M. J. Romão, and C. M. Fontes. 2003. Cellulosome assembly revealed by the crystal structure of the cohesin-dockerin complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:13809-13814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, C. G., Z. Y. Pu, R. L. Moritz, R. J. Simpson, A. Bacic, A. E. Clarke, and S. L. Mau. 1994. Molecular cloning of a gene encoding an arabinogalactan-protein from pear (Pyrus communis) cell suspension culture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10305-10309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung, A. Y., H. Wang, and H. M. Wu. 1995. A floral transmitting tissue-specific glycoprotein attracts pollen tubes and stimulates their growth. Cell 82:383-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke, A. E., R. L. Anderson, and B. A. Stone. 1979. Form and function of arabinogalactans and arabinogalactan-proteins. Phytochemistry 18:521-540. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies, G., and B. Henrissat. 1995. Structures and mechanisms of glycoside hydrolases. Structure 3:853-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du, H., R. J. Simpson, R. L. Moritz, A. E. Clarke, and A. Bacic. 1994. Isolation of the protein backbone of an arabinogalactan-protein from the styles of Nicotiana alata and characterization of a corresponding cDNA. Plant Cell 6:1643-1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felix, C. R., and L. G. Ljungdahl. 1993. The cellulosome: the exocellular organelle of Clostridium. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:791-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fincher, G. B., W. H. Sawyer, and B. A. Stone. 1974. Chemical and physical properties of an arabinogalactan-peptide from wheat endosperm. Biochem. J. 139:535-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujimoto, Z., A. Kuno, S. Kaneko, H. Kobayashi, I. Kusakabe, and H. Mizuno. 2002. Crystal structures of the sugar complexes of Streptomyces olivaseoviridis E-86 xylanase: sugar binding structure of the family 13 carbohydrate binding module. J. Mol. Biol. 316:65-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaspar, Y., K. L. Johnson, J. A. McKenna, A. Bacic, and C. J. Schultz. 2001. The complex structures of arabinogalactan-proteins and the journey towards understanding function. Plant Mol. Biol. 47:161-176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henrissat, B. 1991. A classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem. J. 280:309-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirabayashi, J., S. K. Dutta, and K. Kasai. 1998. Novel galactose-binding proteins in Annelida. Characterization of 29-kDa tandem repeat-type lectins from the earthworm Lumbricus terrestris. J. Biol. Chem. 273:14450-14460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirabayashi, J., T. Hashidate, Y. Arata, N. Nishi, T. Nakamura, M. Hirashima, T. Urashima, T. Oka, M. Futai, W. E. Muller, F. Yagi, and K. Kasai. 2002. Oligosaccharide specificity of galectins: a search by frontal affinity chromatography. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1572:232-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirabayashi, J., Y. Arata, and K. Kasai. 2003. Frontal affinity chromatography as a tool for elucidation of sugar recognition properties of lectins. Methods Enzymol. 362:353-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ichinose, H., M. Yoshida, T. Kotake, A. Kuno, K. Igarashi, Y. Tsumuraya, M. Samejima, J. Hirabayashi, H. Kobayashi, and S. Kaneko. 2005. An exo-β-1,3-galactanase having a novel β-1,3-galactan binding module from Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J. Biol. Chem. 280:25820-25829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito, S., A. Kuno, R. Suzuki, S. Kaneko, Y. Kawabata, I. Kusakabe, and T. Hasegawa. 2004. Rational affinity purification of native Streptomyces family 10 xylanase. J. Biotechnol. 110:137-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juy, M., A. G. Amit, P. M. Alzari, R. J. Poljak, M. Claeyssens, P. Béguin, and J. P. Aubert. 1992. Three-dimensional structure of a thermostable bacterial cellulase. Nature 357:89-91. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knox, J. P. 1995. The extracellular matrix in higher plants. 4. Developmentally regulated proteoglycans and glycoproteins of the plant cell surface. FASEB J. 9:1004-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotake, T., S. Kaneko, A. Kubomoto, M. A. Haque, H. Kobayashi, and Y. Tsumuraya. 2004. Molecular cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of a Trichoderma viride endo-β-(1→6)-galactanase gene. Biochem. J. 377:749-755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kreuger, M., and G. J. van Holst. 1996. Arabinogalactan proteins and plant differentiation. Plant Mol. Biol. 30:1077-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuno, A., S. Kaneko, H. Ohtsuki, S. Ito, Z. Fujimoto, H. Mizuno, T. Hasegawa, K. Taira, I. Kusakabe, and K. Hayashi. 2000. Novel sugar-binding specificity of the type XIII xylan-binding domain of a family F/10 xylanase from Streptomyces olivaceoviridis E-86. FEBS Lett. 482:231-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lytle, B. L., B. F. Volkman, W. M. Westler, M. P. Heckman, and J. H. Wu. 2001. Solution structure of a type I dockerin domain, a novel prokaryotic, extracellular calcium-binding domain. J. Mol. Biol. 307:745-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majewska-Sawka, A., and E. A. Nothnagel. 2000. The multiple roles of arabinogalactan proteins in plant development. Plant Physiol. 122:3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsui, I., K. Ishikawa, E. Matsui, S. Miyairi, S. Fukui, and K. Honda. 1991. Subsite structure of Saccharomycopsis alpha-amylase secreted from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 109:566-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mau, S. L., C. G. Chen, Z. Y. Pu, R. L. Moritz, R. J. Simpson, A. Bacic, and A. E. Clarke. 1995. Molecular cloning of cDNAs encoding the protein backbones of arabinogalactan-proteins from the filtrate of suspension-cultured cells of Pyrus communis and Nicotiana alata. Plant J. 8:269-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montfort, W., J. E. Villafranca, A. F. Monzingo, S. R. Ernst, B. Katzin, E. Rutenber, N. H. Xoung, R. Hamlin, and J. D. Robertus. 1987. The three-dimensional structure of ricin at 2.8 Å. J. Biol. Chem. 262:5398-5403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura, S., F. Yagi, K. Totani, Y. Ito, and J. Hirabayashi. 2005. Comparative analysis of carbohydrate-binding properties of two tandem repeat-type Jacalin-related lectins, Castanea crenata agglutinin and Cycas revoluta leaf lectin. FEBS J. 272:2784-2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pellerin, P., and J. M. Brillouet. 1994. Purification and properties of an exo-(1→3)-β-d-galactanase from Aspergillus niger. Carbohydr. Res. 264:281-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roy, S., G. Y. Jauh, P. K. Hepler, and E. M. Lord. 1998. Effects of Yariv phenylglycoside on cell wall assembly in the lily pollen tube. Planta 204:450-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schindelman, G., A. Morikami, J. Jung, T. I. Baskin, N. C. Carpita, P. Derbyshire, M. C. McCann, and P. N. Benfey. 2001. COBRA encodes a putative GPI-anchored protein, which is polarly localized and necessary for oriented cell expansion in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 15:1115-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schultz, C. J., K. L. Johnson, G. Currie, and A. Bacic. 2000. The classical arabinogalactan protein gene family of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12:1751-1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sommer-Knudsen, J., A. Bacic, and A. E. Clarke. 1998. Hydroxylproline-rich plant glycoproteins. Phytochemistry 47:483-497. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Somogyi, M. 1952. Notes on sugar determination. J. Biol. Chem. 195:19-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun, W., Z. D. Zhao, M. C. Hare, M. J. Kieliszewski, and A. M. Showalter. 2004. Tomato LeAGP-1 is a plasma membrane-bound, glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored arabinogalactan-protein. Physiol. Plant. 120:319-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsumuraya, Y., N. Mochizuki, Y. Hashimoto, and P. Kováč. 1990. Purification of an exo-β-(1→3)-d-galactanase of Irpex lacteus (Polyporus tulipiferae) and its action on arabinogalactan-proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 265:7207-7215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Hengel, A. J., Z. Tadesse, P. Immerzeel, H. Schols, A. van Kammen, and S. C. de Vries. 2001. N-Acetylglucosamine and glycosamine-containing arabinogalactan proteins control somatic embryogenesis. Plant Physiol. 125:1880-1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Hengel, A. J., and K. Roberts. 2002. Fucosylated arabinogalactan-proteins are required for full root cell elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 32:105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Hengel, A. J., and K. Roberts. 2003. AtAGP30, an arabinogalactan-protein in the cell walls of the primary root, plays a role in root regeneration and seed germination. Plant J. 36:256-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willats, W. G., and J. P. Knox. 1996. A role for arabinogalactan-proteins in plant cell expansion: evidence from studies on the interaction of beta-glucosyl Yariv reagent with seedlings of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 9:919-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu, H. M., H. Wang, and A. Y. Cheung. 1995. A pollen tube growth stimulatory glycoprotein is deglycosylated by pollen tubes and displays a glycosylation gradient in the flower. Cell 82:395-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Youl, J. J., A. Bacic, and D. Oxley. 1998. Arabinogalactan-proteins from Nicotiana alata and Pyrus communis contain glycosylphosphatidylinositol membrane anchors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7921-7926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zverlov, V. V., J. Kellermann, and W. H. Schwarz. 2005. Functional subgenomics of Clostridium thermocellum cellulosomal genes: identification of the major catalytic components in the extracellular complex and detection of three new enzymes. Proteomics 5:3646-3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]