Abstract

Fecal culture for Escherichia coli O157:H7 was compared to rectoanal mucosal swab (RAMS) culture in dairy heifers over a 1-year period. RAMS enrichment culture was as sensitive as fecal culture using immunomagnetic separation (IMS) (P = 0.98, as determined by a chi-square test). RAMS culture is less costly than fecal IMS culture and can yield quantitative data.

Domestic ruminants are the primary reservoir for Escherichia coli O157:H7, and the on-farm ecology of this organism has been studied extensively (2, 4, 11, 18, 20). Environmental reservoirs likely play an important role (6, 10, 12, 14), but individual animals may also contribute significantly to the maintenance and spread of E. coli O157:H7 on the farm. The duration of carriage varies widely between individual animals. Most animals excrete culture-positive feces for less than 1 week, but there are a few animals that are feces positive for several weeks or even months (2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 16, 22). Recent findings (15, 19) that the rectoanal-junction mucosa is a major colonization site for E. coli O157:H7 in the bovine intestine also suggest that host colonization factors may play an important role. Rectoanal mucosal swab (RAMS) culture has been shown to be more sensitive than fecal culture for dairy (21) and feedlot (9) cattle. Immunomagnetic separation (IMS) (23) of E. coli O157 from fecal samples after enrichment culture is often used to increase the sensitivity of fecal culture, but this technique is expensive and does not provide quantitative information in the form of bacterial counts/sample. We hypothesized that RAMS culture is at least as sensitive as fecal IMS with enrichment culture and that, as suggested by Rice et al. (21), RAMS culture could be used to detect carrier animals. To compare the sensitivity of RAMS culture to the sensitivity of fecal culture and to evaluate the ability of RAMS culture to predict the duration of carriage, we conducted a longitudinal study of the natural E. coli O157:H7 status among dairy heifers in which we sampled individual heifers over time at monthly intervals for 12 months, using (i) direct and enriched RAMS culture, (ii) direct fecal culture, and (iii) fecal IMS.

Two university dairy herds were used. Dairy A had a closed herd and raised calves on its premises. Dairy B raised calves on its premises but sent heifers to be raised at another facility until they were 12 to 14 months old, so the dairy B heifers were at the heifer-raising facility for the duration of the study. Hutch calves were fed milk replacer at dairy A and waste milk at dairy B, and after weaning at both dairies the animals were fed a pelleted grain calf starter prepared at a local feed mill. The calf starter consisted of barley, corn, oats, soybean meal, vitamins, minerals, and a coccidiostat. After weaning, calves were placed in group pens containing three to five animals per pen, and after several weeks they moved to pens with larger numbers of heifers per pen.

At the initial visit to each dairy, a cohort of 20 heifers that were 2 to 6 months old was identified. At each subsequent monthly visit, newly weaned heifers were added to the study until each herd contained 40 animals. Heifers were sampled once each month for 12 months, and there was not more than a 15-day variation in the interval. Each animal that yielded a positive sample at the monthly visit was resampled 5 to 9 days later. At each visit, two samples were collected from each animal: freshly passed feces and a rectoanal mucosal swab. The order of sample collection was always (i) free-catch feces (if available), (ii) RAMS, and then (iii) feces collected by rectal palpation if free catch was not available. RAMS samples were collected and processed as previously described (21). Briefly, a sterile foam-tipped applicator (catalog no. 10812-022; VWR International, Buffalo Grove, IL) was inserted approximately 2 to 5 cm into the anus, and the circumference of the rectoanal- junction mucosa was swabbed (21). Each swab was placed immediately into a culture tube containing 3 ml ice-cold Trypticase soy broth (TSB) (Difco Laboratories, Detroit MI). Fecal samples (≥15 g) were placed immediately into sterile Whirl-Pak bags (Nasco, Fort Atkinson, WI). All samples were kept on ice to prevent bacterial replication until laboratory processing within 6 h after collection.

Swabs in cold TSB were vortexed for 1 min, and 10-fold serial dilutions in a sterile saline solution were spread plated onto individual sorbitol MacConkey agar plates (SMac) (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) containing cefixime (50 ng/ml; Wyeth-Ayerst, Pearl River NY), potassium tellurite (2.5 μg/ml; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis MO), vancomycin (40 μg/ml; Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO), and 4-methylumbelliferyl-beta-d-glucuronic acid dihydrate (100 μg/ml; Biosynth Ag, Switzerland); this medium was designated SMac-CTVM. SMacCTVM plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h. Sorbitol- and beta-glucuronidase-negative colonies were confirmed to be E. coli O157 using a latex agglutination test (Pro Lab Diagnostics, Canada). Immediately after direct plating, RAMS samples in TSB were incubated on a rotary shaker (150 rpm) at 37°C for 18 h. The samples that did not yield E. coli O157 by direct culture were serially diluted and spread plated onto SMac-CTVM. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h, and E. coli O157 colonies were identified as described above for direct RAMS culture. Feces (10 g) were weighed into 90 ml cold TSB and mixed. Plating of fecal solutions onto SMac-CTVM, incubation, and colony counting were performed as described above for RAMS samples.

After samples were plated for direct culture of E. coli O157, the feces-TSB mixtures were incubated at 42°C for 24 h. Immunomagnetic separation with anti-O157 Dynabeads (Dynal, Olso, Norway) was then performed by following the manufacturer's directions, using an automated bead retriever (Dynal). Bead suspensions were plated onto SMac containing cefixime and potassium tellurite and incubated at 37°C for 18 h, and E. coli O157 colonies were identified as described above for direct RAMS culture.

To compare the sensitivity of culture of RAMS samples to the sensitivity of direct fecal culture and fecal culture with IMS enrichment, the overall and monthly proportions of positive samples determined by the different methods were compared using a chi-square contingency table (7). For comparisons of test method sensitivity, only monthly visit data were used, whereas to estimate the duration of carriage, both the data from each monthly visit and the data from follow-up visits were used. (Follow-up visits occurred 1 week after monthly sampling to retest heifers that were culture positive at the monthly visit.) Duration was estimated by determining the interval (in days) between the first and last consecutive sample visits that yielded E. coli O157-positive samples and adding 1 day. If a positive sample was collected more than 30 days after a previous positive sample was collected, a new episode of carriage was inferred. Two positive results with one or more intervening negative tests were considered to be different carriage episodes. To explore the relationship between duration of carriage and the amounts of E. coli O157 bacteria contributed by individual animals, we calculated the log10 geometric mean of the fecal E. coli O157 counts from each sample date that fell within the duration. Data were analyzed using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Wash.) and SAS (SAS, Cary, N.C.).

Most of the heifers remained in good health during the study period; the only exception was one animal at dairy B that died of causes unrelated to the study (Table 1). A total of 874 RAMS samples and 874 fecal samples were collected from both dairies over the sampling period. Of these, 73 were collected at follow-up visits that were made about 1 week after the monthly visit to resample positive heifers. The prevalence of culture-positive samples for free-catch samples was similar to the prevalence of culture-positive samples for rectally retrieved fecal samples (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Numbers of heifers longitudinally sampled at each monthly sampling visit

| Sampling month | Dairy A (Washington State University) | Dairy B (University of Idaho) |

|---|---|---|

| April | 20a | 20a |

| May | 32 | 0b |

| June | 31 | 28 |

| July | 34 | 29 |

| August | 39 | 29 |

| September | 40 | 32 |

| October | 40 | 40 |

| November | 40 | 36c |

| December | 40 | 40 |

| January | 40 | 40 |

| February | 40 | 39d |

| March | 40 | 26e |

Heifers were enrolled at 2 months of age and were sampled repeatedly throughout the study period.

Calves were transported to the heifer-raising facility in May and were unavailable for sampling.

Four heifers were unavailable for sampling.

One of the study heifers died of causes unrelated to the study.

Mature heifers were moved back to the dairy prior to the sampling date and were unavailable for sampling.

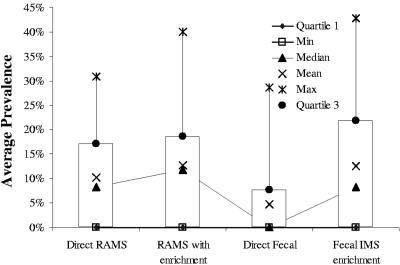

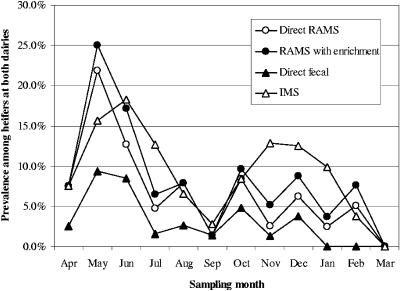

Overall, RAMS culture (direct and enriched results were combined to include all animals with a culture-positive RAMS sample) was as sensitive as fecal IMS with enrichment culture (Table 2). Fecal culture with IMS enrichment detected 87 positive samples in 874 samples (10.0%), and RAMS culture (direct and enrichment) detected 84 positive samples in 840 samples (10.0%) (P = 0.98, as determined by a chi-square test). Direct fecal plating without the IMS enrichment step was the least sensitive method, detecting 3.2% positive samples. Overall, direct fecal plating was significantly less sensitive than either direct or enrichment RAMS culturing (P < 0.001, as determined by a chi-square test). None of the observed differences in the month-specific prevalence values determined by the different methods were statistically significant (Fig. 1 and 2). The distributions of average monthly prevalence detected by fecal IMS and RAMS culture with enrichment overlapped (Fig. 1). The point prevalence of E. coli O157 among individual heifers varied greatly from month to month at both dairies. In general, the monthly point prevalence detected by RAMS culture with enrichment was similar to that detected by fecal IMS with enrichment, and for most months it appeared to be higher than that detected by direct fecal culture, although the difference was not statistically significant in any month (for each month-specific comparison the P values were greater than 0.09, as determined by a chi-square test) (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Total numbers of samples that were culture positive for E. coli O157

| Method | Total no. positive for E. coli O157 | Total no. tested | % Positivea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct fecal plating | 28 | 874 | 3.2 A |

| Fecal IMS enrichment | 87 | 874 | 10.0 B |

| Direct RAMS plating | 62 | 874 | 7.1 C |

| RAMS culture with enrichment | 84 | 840b | 10.0 B |

Values followed by different letters were significantly different (P < 0.05, as determined by a chi-square test).

Thirty-four RAMS samples that were negative by direct plating methods were accidentally discarded and therefore unavailable for enrichment.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of monthly prevalence of E. coli O157, as detected by different screening methods. Min, minimum monthly prevalence; Quartile 1, first quartile (25th percentile); Max, maximum monthly prevalence; Quartile 3, third quartile (75th percentile).

FIG. 2.

Monthly prevalence of E. coli O157 in dairy heifers at both university dairies, as determined by different test methods.

To test the hypothesis that positive RAMS culture identifies colonized animals and differentiates them from animals that are not colonized but are passively shedding E. coli O157 in their feces, we compared the duration of carriage for the heifers that were initially identified as E. coli O157 positive by fecal IMS culture to the duration of carriage for the heifers that were initially identified as E. coli O157 positive by RAMS culture. Of 77 E. coli O157-positive heifers, 12 (15.6%) were first detected by all three methods (RAMS culture, direct fecal culture, and fecal IMS). Twenty-four (31.2%) were first detected by both RAMS culture and fecal IMS, 11 (14.3%) were first detected by direct RAMS culture, 3 (3.9%) were first detected by enriched RAMS culture, and 27 (35.1%) were first detected by IMS alone. Of the 17 colonizations with estimated durations of 15 days or longer, 7 (41.2%) were first detected by all three methods, 6 (35.3%) were first detected by both RAMS culture and IMS, and 4 (23.5%) were first detected by IMS.

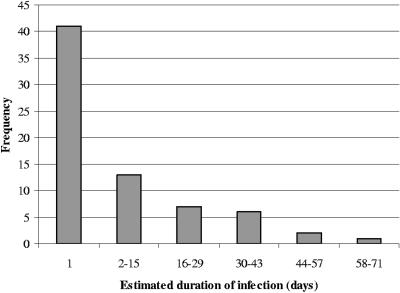

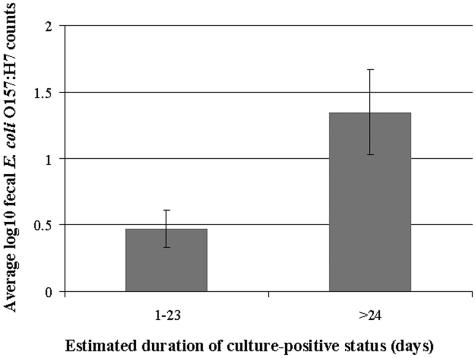

To examine the role of long-term carriers in the ecology of E. coli O157 on dairy farms, we estimated the duration of carriage in each positive animal. The majority of estimated durations were brief, and a minority of animals were culture positive on four or five consecutive visits over a 44- to 66-day period (Fig. 3). For each category of duration that we observed, the average log fecal E. coli O157 counts varied, but in general, heifers that were culture positive for 23 days or longer had higher average fecal E. coli O157 counts than heifers that were culture positive for shorter durations (Fig. 4). The high numbers of E. coli O157 in the feces correlated with high numbers of E. coli O157 detected on swab samples by direct RAMS culture (r = 0.77) (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Estimated duration of E. coli O157 carriage detected by any method for heifers from two university dairies.

FIG. 4.

Average log10 fecal E. coli O157 counts for estimated duration of culture-positive status in two duration categories. There were 64 occurrences in the <23-day duration category and 9 occurrences in the 23- to 66-day category. The error bars indicate standard errors of the means.

To describe the genetic relationships between E. coli O157 strains recovered during this study, isolates were subtyped using standard pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of restriction enzyme-digested chromosomal DNA (6). If a restriction pattern differed by one or more bands, a different type was assigned. Of 54 typed isolates, 35 (61%) were type A, 6 (11.1%) were type B, 3 (5.5%) were type C, 3 (5.5%) were type D, and types E through K were each represented by unique patterns seen only once. In the majority of animals, identical PFGE types were detected in both RAMS- and fecal culture-positive samples; however, on two occasions distinct PFGE types were detected in the feces compared with the RAMS samples from the same animal (data not shown). Animals that were culture positive on more than one consecutive sampling day carried identical PFGE types, suggesting, although not proving, that one carriage episode occurred over the duration of the experiment.

This study demonstrated that RAMS culture has a sensitivity similar to that of IMS with enrichment fecal culture and better overall sensitivity than direct fecal plating for E. coli O157 screening in cattle. Therefore, an animal that was E. coli O157 positive as determined from a fecal sample was almost always identified as culture positive by RAMS culture. This is consistent with previous findings (9, 21) and confirms these findings for the first time for a large cohort of naturally infected dairy heifers sampled longitudinally over time. The use of IMS is often considered to be the most sensitive culture method for screening cattle for E. coli O157, but RAMS culture has the advantage of being less costly and more rapid than IMS, and only the direct method yields quantitative results. Direct plating of RAMS samples alone was significantly more sensitive overall than non-IMS fecal culture and provided results within 24 h.

The most surprising finding of this study was that the concentration of E. coli O157 in feces was positively associated with the estimated duration of culture-positive status. This suggests that colonized animals make a significant contribution to pathogen load on farms and supports the concept of “supershedders” (1, 17). For example, the single animal in our study whose culture-positive status lasted for 66 days (Fig. 4) shed, on average, 3.0 log bacteria per g of feces daily. Using a conservative estimate of per-heifer daily fecal output (24) of approximately 20 kg, this individual would have shed more than 109 CFU during the 66-day period. By comparison, animals that were culture positive for 1 day were mostly characterized by very low fecal counts. This finding is also consistent with the demonstration by Low et al. that mucosal carriage of E. coli O157 at the rectoanal junction is associated with high-level fecal excretion and that high-level excreters are associated with low-level excreting penmates, suggesting that the high-level excreters were the source of E. coli O157 for the other cattle (15).

The results of our estimation of the duration of culture-positive status in this study were consistent with the results of other longitudinal studies (2, 4, 8). Duration was estimated by calculating the time between the first and last successive positive samples, so there was potential for both under- and overestimating the duration of culture-positive status. For example, a true culture-positive duration falling between two sample visits would have been overestimated. On the other hand, the less-than-perfect sensitivity of culture may have biased our estimate of duration in the other direction by failing to detect positive samples which would have resulted in more animals being classified as longer-duration carriers.

A primary rationale for conducting this study was the prospect that RAMS culture would be a means to identify colonized animals and would therefore provide cattle producers with a method (for example, segregation or culling of colonized animals) for reducing the total pathogen load on their premises. Although this study did not reproduce the findings of Rice et al. (21), which showed that there was a significant association between long duration of carriage and RAMS culture-positive status, it did confirm the sensitivity of RAMS culture as a screening tool for culture-positive status in cattle. A definitive conclusion about the usefulness of RAMS culture to predict the duration of shedding requires additional data from a larger number of animals.

In conclusion, we found that (i) for detecting E. coli O157 in cattle, RAMS culture with enrichment is as sensitive as fecal IMS and is less costly, (ii) direct RAMS culture provides quantitative data and is more sensitive than direct fecal culture without IMS, (iii) RAMS culture-positive status does not always predict long duration of carriage but does provide a practical screening method for positive animals, and (iv) there is a positive association between duration of positive status and fecal E. coli O157 counts. The last, unexpected finding supports the idea that supershedders exist and that if we could identify these animals, we would be able to eliminate a large source of pathogens in the farm environment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Idaho Agriculture Experiment Station; by the National Cattlemen's Beef Association; by the National Research Initiative of the USDA Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service (grants 99-35201-8539 and 04-04562); by Public Health Service grants NO1-HD-0-3309, U54-AI-57141, P20-RR16454, and P20-RR15587 from the National Institutes of Health; and by grants from the United Dairymen of Idaho.

We acknowledge Rob Adair, Jennifer Carstens, Lonie Austin, Hanna Knecht, Richard Knight, and Russ McClanahan for animal handling and technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bach, S. J., L. J. Selinger, K. Stanford, and T. A. McAllister. 2005. Effect of supplementing corn- or barley-based feedlot diets with canola oil on faecal shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by steers. J. Appl. Microbiol. 98:464-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Besser, T. E., D. D. Hancock, L. C. Pritchett, E. M. McRae, D. H. Rice, and P. I. Tarr. 1997. Duration of detection of fecal excretion of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in cattle. J. Infect. Dis. 175:726-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, C. A., B. G. Harmon, T. Zhao, and M. P. Doyle. 1997. Experimental Escherichia coli O157:H7 carriage in calves. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:27-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobbold, R., and P. Desmarchelier. 2000. A longitudinal study of Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC) prevalence in three Australian dairy herds. Vet. Microbiol. 71:125-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cray, W. C., Jr., and H. W. Moon. 1995. Experimental infection of calves and adult cattle with Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1586-1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis, M. A., D. D. Hancock, D. H. Rice, D. R. Call, R. DiGiacomo, M. Samadpour, and T. E. Besser. 2003. Feedstuffs as a vehicle of cattle exposure to Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enterica. Vet. Microbiol. 95:199-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean, A. G., J. A. Dean, D. Coulombier, K. A. Brendel, D. C. Smith, A. H. Burton, R. C. Dicker, K. Sullivan, R. F. Fagan, and T. C. Arner. 1994. Epi Info, version 6: a word processing, database, and statistics program for epidemiology on microcomputers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.

- 8.Ezawa, A., F. Gocho, M. Saitoh, T. Tamura, K. Kawata, T. Takahashi, and N. Kikuchi. 2004. A three-year study of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 on a farm in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 66:779-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenquist, M. A., J. S. Drouillard, J. M. Sargeant, B. E. Depenbusch, X. Shi, K. F. Lechtenberg, and T. G. Nagaraja. 2005. Comparison of rectoanal mucosal swab cultures and fecal cultures for determining prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in feedlot cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6431-6433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hancock, D., T. Besser, J. Lejeune, M. Davis, and D. Rice. 2001. The control of VTEC in the animal reservoir. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 66:71-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hancock, D., D. Rice, L. A. Thomas, D. Dargatz, and T. Besser. 1997. Epidemiology of Escherichia coli O157 in feedlot cattle. J. Food Prot. 60:462-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hancock, D. D., T. E. Besser, D. H. Rice, E. D. Ebel, D. E. Herriott, and L. V. Carpenter. 1998. Multiple sources of Escherichia coli O157 in feedlots and dairy farms in the northwestern USA. Prev. Vet. Med. 35:11-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hancock, D. D., T. E. Besser, D. H. Rice, D. E. Herriott, and P. I. Tarr. 1997. A longitudinal study of Escherichia coli O157 in fourteen cattle herds. Epidemiol. Infect. 118:193-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kudva, I., K. Blanch, and C. J. Hovde. 1998. Analysis of Escherichia coli O157:H7 survival in ovine or bovine manure and manure slurry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3166-3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Low, J. C., I. J. McKendrick, C. McKechnie, D. R. Fenlon, S. W. Naylor, C. Currie, D. G. E. Smith, L. Allison, and D. L. Gally. 2005. Rectal carriage of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 in slaughtered cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:93-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magnuson, B. A., M. Davis, S. Hubele, P. R. Austin, I. T. Kudva, C. J. Williams, C. W. Hunt, and C. J. Hovde. 2000. Ruminant gastrointestinal cell proliferation and clearance of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect. Immun. 68:3808-3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews, L., I. J. McKendrick, H. Ternent, G. J. Gunn, B. Synge, and M. E. J. Woolhouse. 2006. Super-shedding cattle and the transmission dynamics of Escherichia coli O157. Epidemiol. Infect. 134:131-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mechie, S. C., P. A. Chapman, and C. A. Siddons. 1997. A fifteen month study of Escherichia coli 0157:H7 in a dairy herd. Epidemiol. Infect. 118:17-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naylor, S. W., J. C. Low, T. E. Besser, A. Mahajan, G. J. Gunn, M. C. Pearce, I. J. McKendrick, D. G. Smith, and D. L. Gally. 2003. Lymphoid follicle-dense mucosa at the terminal rectum is the principal site of colonization of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the bovine host. Infect. Immun. 71:1505-1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neaves, P., J. Deacon, and C. Bell. 1994. A survey of the incidence of E. coli O157 in the UK dairy industry. Int. Dairy J. 4:679-696. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice, D. H., H. Q. Sheng, S. A. Wynia, and C. J. Hovde. 2003. Rectoanal mucosal swab culture is more sensitive than fecal culture and distinguishes Escherichia coli O157:H7-colonized cattle and those transiently shedding the same organism. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4924-4929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanderson, M. W., T. E. Besser, J. M. Gay, C. C. Gay, and D. D. Hancock. 1999. Fecal Escherichia coli O157:H7 shedding patterns of orally inoculated calves. Vet. Microbiol. 69:199-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tutenel, A. V., D. Pierard, D. Vandekerchove, J. Van Hoof, and L. De Zutter. 2003. Sensitivity of methods for the isolation of Escherichia coli O157 from naturally infected bovine faeces. Vet. Microbiol. 94:341-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkerson, V. A., D. R. Mertens, and D. P. Casper. 1997. Prediction of excretion of manure and nitrogen by Holstein dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 80:3193-3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]