Abstract

Context: Health professionals are exposed to critical influences and pressures when socialized into their work environments. Little is known about the organizational socialization of certified athletic trainers (ATs) in the collegiate context.

Objective: To discuss the organizational influences and quality-of-life issues as each relates to the professional socialization of ATs working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting.

Design: A qualitative design of in-depth interviews and follow-up electronic interviews was used to examine the organizational socialization of ATs.

Setting: Participants associated with Division I athletic programs from 4 National Athletic Trainers' Association districts volunteered for the study.

Participants: A total of 11 men and 5 women participated in the study, consisting of 14 ATs and 2 athletic directors.

Data Collection and Analysis: Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed inductively. A peer review, member checks, and data source triangulation were performed to establish trustworthiness.

Results: Two categories emerged that provide insight into the experiences that affected the professional socialization of the ATs: organizational influences and quality-of-life issues. The data indicate that the participants in this study were heavily influenced by the bureaucratic tendencies of the Division I athletic organizations in which they worked. The participants were extremely concerned about the diminished quality of life that may result from being an AT in this context. They were, however, able to maintain a commitment to delivering quality care to the student-athletes despite these influences. High work volume and low administrative support were commonly cited as problems, thus creating concern about diminished quality of life and the fear of burnout.

Conclusions: The AT's role appears not only rewarding but also challenging. The reward is working closely with patients and developing an interpersonal bond; the challenge is dealing with a bureaucratic structure and balancing one's professional and personal lives to prevent burnout. Thought should be given to using intervention strategies to mitigate the negative influences on the AT's role.

Keywords: bureaucracy, qualitative research, role strain

Professional socialization is a developmental process whereby individuals acquire the norms, knowledge, and skills that allow them to function in a particular role. 1 Although socialization has been carefully investigated over time, professional socialization in the allied health professions has recently gained more attention. As Purtilo 2 stated,

An individual's “socialization” into a profession has always been recognized as important, and indeed, inevitable. But only in recent years has the socialization process been viewed as ambipotent, that is, a process carrying the power to affect either positive or negative results for health professionals and society. Thus it is understandable that the idea of socialization is receiving new and careful attention.

Professional socialization includes not only the formal educational experiences before entering a work setting but also the experiences within one's work setting or work organization. However, as Wilensky 3 identified quite some time ago, professionals often work in complex organizations that clash with the ideals of professionalism. As allied health professionals are socialized into their work organizations, they are exposed to critical influences and pressures that affect them in many ways. More recently, Winterstein 4 identified the collegiate work organization as very complicated in that many demands are competing for one's attention. Indeed, the work context and role requirements of certified athletic trainers (ATs) are particularly complex, especially in a collegiate environment in which the sport culture's focus on winning and competing at a high level is juxtaposed with providing high-quality health care to injured athletes. How ATs develop professionally and deal with these organizational influences and how they are socialized into their professional role was the focus of this study.

This study presents 2 emergent categories—organizational influences and quality-of-life issues—from a larger qualitative study that investigated the professional socialization of ATs working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I setting. The aim of the overall investigation was to gain insight and understanding about the professional socialization of the ATs and to explore the socialization experiences. Because of the voluminous data, one category explaining the process model of professional socialization that resulted from the larger study is presented elsewhere. 5 Thus, readers are encouraged to examine these findings to gain a holistic understanding of the professional socialization process that emerged.

METHODS

Maxwell 6 suggested that qualitative methods are especially suited for understanding meaning; contexts in which participants work; and processes rather than outcomes and identifying critical influences and, consequently, generating theory about them. Thus, a qualitative approach was used to learn about the socialization experiences of the participants.

Subjects

A total of 16 individuals, 11 men and 5 women, participated in the study. At the time of the study, 12 participants (11 full-time staff and 1 graduate assistant) were currently ATs in the NCAA Division I setting. Two participants were formerly head athletic trainers in the NCAA Division I setting but currently held positions elsewhere (1 clinical setting, 1 educational setting). The remaining 2 participants were collegiate athletic directors (1 head athletic director and 1 associate-level athletic director). Excluding the graduate assistant, the 11 current ATs in the NCAA Division I setting averaged 9.2 years of experience in that setting and 11.7 years as an AT. The ATs who were full-time staff were from 4 different NCAA Division I athletic conferences. The AT participants represented National Athletic Trainers' Association Districts 3, 4, 5, and 9. Northern Illinois University's Institutional Review Board granted permission to conduct the study, and participants were required to sign and return informed consent forms.

Participants were purposefully selected for interviewing. I initially selected 9 individuals whom I knew and in whom I had confidence that they would speak honestly about their work culture and critical events that have influenced their professional lives. I selected these interviewees according to availability, and then I obtained a snowball sample (ultimately leading to 5 additional AT participants and 2 athletic directors) to gain access to ATs in the Division I setting. That is, once the initial participants were interviewed, I asked them the names of other ATs whom I was not familiar with but who they thought would be willing to give an interview.

Procedures

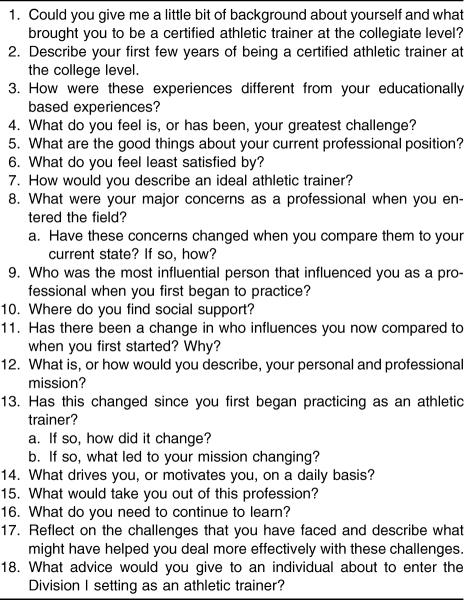

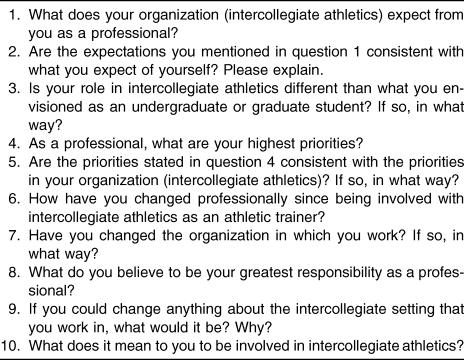

In-depth, semistructured interviews were completed with each participant (Appendix 1). Five interviews were conducted in person, and 11 interviews were telephone interviews. Second interviews were conducted electronically (via e-mail) with 6 interviewees, all of whom were currently practicing ATs in the collegiate setting. The second interviews were necessary to clarify findings, further learn of the participants' experiences, substantiate the emergent findings of the study, and gain more depth of information regarding the participants' perceptions of the work environment. Appendix 2 displays the electronic interview questions.

The trustworthiness of the study was established by peer review, member checks, and data source triangulation. The interview transcripts, coding sheets, and interpretations were presented to a peer with more than 20 years of qualitative research experience. The peer reviewed the data and findings to determine that the process was conducted in an appropriate and systematic manner. The member checks were performed by explaining the findings to 3 of the study participants. These participants examined the emergent categories to determine that they were credible according to their experiences. In all instances, the findings were substantiated and the participants agreed with the findings. Data collection was triangulated by interviewing both current and former ATs, as well as 2 athletic directors and 1 graduate assistant AT. Comparing multiple sources of data helps reduce the possibility of misrepresenting the data. 7

Interviews were tape recorded and I transcribed them verbatim. Electronic interview data were simply cut-and-pasted into a word-processor document. The interview data were analyzed inductively, borrowing from grounded theory methodology 8–10 in the following manner:

Key information related to the research purpose was identified in the transcripts. This was performed in an ongoing manner as each interview was conducted.

Each section of information was examined and given a conceptual label that represented it. These conceptual labels were written in the margins of the transcripts and transposed to index cards.

The concepts that were documented in the margins were constantly compared with one another and placed into like categories.

The categories and their contents were examined and compared with one another; the relationships among the categories were explored and collapsed together or separated where appropriate.

All data were constantly reevaluated for discrepancies, and categories were revised as necessary.

RESULTS

Three categories emerged from the original 2002 study: (1) role dynamics—the process of professional socialization, (2) organizational influences, and (3) quality-of-life issues. As aforementioned, the first category identified a predictable sequence of experiences among collegiate ATs and was presented as a separate manuscript. 5 The current study presents the remaining categories and serves to illuminate the critical aspects of the role ATs face in rendering health care in the NCAA Division I context, particularly as individuals evolved in their professional role.

Organizational Influences

Consistently, most participants indicated that the dynamics of their position were grounded on attempting to render high quality of care, despite the bureaucratic tendencies of the collegiate organization. The bureaucracy of collegiate athletics was a surprise to the participants, and they were often unprepared for such influences. Moreover, the participants were not always able to affect the way in which their work was structured (ie, when practices were held). Although the ATs expected a degree of autonomy and freedom to make decisions at their discretion (under the supervision of a team physician), the bureaucratic aspects of the culture, the unwritten aspects of the organizational hierarchy, and pressures to win created an unsettling environment that appeared to devalue an AT's role. Referring to the organizational bureaucracy, specifically a personnel hierarchy and political environment, one participant stated,

We are, in theory, [the coaches'] equal, but whether it's written or not we still work for them. That was really highlighted about a year and a half ago as a head [athletic] trainer with a personnel issue with a coach who said, “I don't want this particular [athletic trainer working with the team]…” Those kind of things, knowing I guess that we are on the bottom rung of the ladder, at times [is frustrating].

Consistent with many bureaucratic organizations, collegiate athletics emphasize efficiency. For example, one AT stated that the athletic directors expected him to provide efficient health care:

We were doing what was asked of us…and doing it as well as we could do it with what we had. And my perception from the administration was that that was effective and efficient. So, [the administration thought] we really don't need to do anything to make things better for [the athletic training staff] because you're doing the job with what you have.

When discussing his professional mission, another AT automatically incorporated that the leaders (athletic directors) of the administration expected efficiency from him:

First and foremost, [my mission is] to provide the best quality of health care to our student-athletes. I mean that's why I'm hired here at E1 University…Number 2, the unwritten part of our job description, is to educate our [athletic training students] and…somewhere in there is [to do it in] the most efficient and cost-effective way.

The collegiate athletics organization that many of the ATs knew as undergraduates and graduate students was unlike the organization they experienced as full-time staff. Alluding to the bureaucratic aspects of the organization, one participant commented

I never expected there to be so much political involvement at the intercollegiate level. As an undergraduate, I expected to be able to focus on treating the athletes. However, I have come to realize that, by being the “middle man” between the athletes, coaches, and administration, I have had to spend much of my time communicating and getting involved on a political level in the negotiation of what is good or not good for the health of the athlete.

Regarding the political nature of collegiate athletics, a different participant exclaimed,

I would love to get rid of the bureaucracy involved in college athletics and create more fairness among the sports. I would love to be able to just do my job and not have to answer to everyone from coaches to administrators. Just allow me to do what I know best and stop micro-managing an area [they— the administration—know little about].

Attempting to deliver quality health care to injured athletes at one institution was met with resistance, as health care to the athletes was not an organizational priority. For example, when asked about the greatest challenges faced in collegiate athletics, one former head AT said,

I would say dealing with coaches and administrators. And the reason why is because a lot of times I felt that their primary concern for the athlete wasn't their health and welfare but just was “when are they going to be back to the field.” Because of that it was frustrating; but also, [from] the administrative standpoint, I did not feel there was a lot of support administratively to back [me]. Obviously as an athletic trainer your primary objective was the health care and well being of the athlete but I don't feel like administratively they supported me as far as that goes. To deal with [the administration] in those times was frustrating.

Another AT made a similar statement, commenting on the organizational hierarchy: “The perception there, whether right or wrong, is that [athletic trainers] are still on the lower end of the ‘totem pole.’” When asked what caused that to occur, the answer was “Money. I mean let's not [kid] ourselves, I think it's money. The revenue sports, football, men's and women's basketball, and volleyball, to an extent within reason, get what they want.” An administrator also clarified this when asked what the priorities of collegiate athletics were: “Well, we have a number of priorities. I would say at the top of the list would be to develop a competitive football program here.” Additionally, the administrator stated another priority: “Increasing the visibility of our program regionally and nationally is important.” Unfortunately, the health and welfare of the student-athletes were secondary thoughts.

The student-athletes' health and welfare was a strong priority with all the ATs. Thus, when athletic training was not perceived as an organizational priority, it was perceived as not only a lack of administrative support but also a lack of concern for the athletes' well-being. One AT explained how he discussed this lack of support with an administrator before resigning his position:

And I said it's because of the fact that I don't see any commitment from the administration to improve the quality of care we can provide our athletes. Then I really don't see any reason to stay here. I said this isn't an issue of me, I said this is an issue of trying to provide quality services to the student athletes.

An important note is that those ATs finding role stability within the organization did find a level of support that seemed to make a difference in terms of their professional goals. For example, one AT stated,

The administration has kind of backed us, [although] not to the point that I would really have liked them to. But, they've backed us to the point where…I think our athletes get innumerable chances to see the physician if need be and their [the athletes'] care has just jumped exponentially. They get such better care now than when I first got here…[and] that [administrative support] has really helped me a lot. It's made me better.

Unfortunately, such comments were the exception rather than the rule. In most instances, the priorities of collegiate athletics were unsettling to the ATs. Although they envisioned and came to expect working in an organization that enjoyed and promoted athletic competition, they soon found an excessive commitment to winning at the Division I level. For example, when asked what he would like to change about his current position, one interviewee said, “I would change the political nature of the job and I would change Division I athletics from a win-at-all-costs program to a program that emphasizes student development through athletics.” These results are a bit surprising considering that all but 1 of the ATs had previously been a graduate assistant athletic trainer in the NCAA Division I setting.

Despite the organizational influences, ATs continued to focus on providing care for the athletes. However, the aforementioned bureaucratic influences of hierarchy and efficiency, as well as the consuming nature of their professional roles, did seem to come at a price. The next theme explicates the consuming nature of the collegiate context, specifically its influence on the professionals' quality of life.

Quality-of-Life Issues

An AT's ability to maintain quality of life and prevent burnout was a premier concern of the participants. Consistently, the participants with more than 2 years of full-time collegiate experience stated that the work environment in which they found themselves was consuming and can deeply affect their quality of life, both inside and outside the organization. When asked what advice they would give to an AT taking a position with Division I collegiate athletics, unequivocally the ATs' statements pertained to preventing burnout and finding a balance between their professional and personal lives. As one AT said,

I guess the advice or recommendations that I would give would be to find a way to realize that there is life outside of intercollegiate athletics. I think that one of the faults, I guess in the way I see it, in that type of a setting is that you, the person, become so wrapped up and involved in the institution, the athletic department, the teams that are associated with the department, the travel with those teams, everything that goes on within that department, that you sometimes lose a sense that there's life outside the department.

A more experienced AT said,

The other thing I'd probably tell them is find time to get away from it. Figure out how to get away from it and still do the job. That's from people at my age level and have been [sic] involved the [number of] years I have, we did not do a good job with that when we were younger. You just went, went, and went, because we didn't know any other way. I think now it's important to try to find a release, to try to make time to do some things so you don't burn out at such a young age.

The consuming role of an AT was even confirmed by an administrator. When asked what advice she would give to an incoming AT, she said,

This is going to sound really terrible coming from me, but not to get consumed in the job. It's terrible coming from me because I am consumed in my job; and I do work 7 days a week most of the school year anyway. That's probably not the healthiest of things to do. But from one “workaholic” to another is not to get consumed in [the job]. Because [the job] can be all-consuming and there is [sic] always people who need or want your time and if you're somebody who has a hard time saying no, or you have to wait, or do this on your own, or whatever, it can be really hard.

Even the less experienced ATs in this study were consumed with their role as collegiate ATs, and this caused significant challenges regarding balancing and juggling their life roles. For instance, one participant said,

The overall challenge for me has been juggling…all the major aspects of my life within athletic training. The political side of things has been rather challenging, but I think overall just being able to juggle my school load [both] as a GA [graduate assistant] and as a…[staff member] right now and making sure I get all my work done.

Another AT believed that the organization expected so much that burnout as a result of role overload was a concern:

Burnout is a huge issue with athletic trainers. I think…adjusting to the collegiate setting, adjusting to how coaches want to be dealt with, how administrators want to be dealt with…I think when [an AT] gets into a full-time situation, as opposed to a graduate or undergraduate [situation], and as you continue to work and be at a place for 1, 2, 5, 7, 10 years, people start to depend on you a little more, people start to look to you for a lot more areas. Trying to be able to separate you away from what you should and shouldn't do, to keep yourself from being burned out. That's something I battle and I guess challenge myself with everyday. Sometimes you just have to say wait a minute, this isn't something we should or shouldn't do…I think if I kept going at the rate that I go during [my primary sport] season…I think it would eventually burn me out and I'd end up babbling somewhere.

The previous 3 quotes relate to the concern of high work volume expressed by the participants. Other organizational influences that affected their quality of life included a lack of administrative support and inadequate salaries. Many of the ATs discussed their roles as they related to being appreciated by the athletes but not by the administration, such as the athletic directors. When discussing what it means to be a collegiate AT, one participant described how he is part of a team effort to help the athletes succeed, yet much of his role was not rewarded or appreciated by the administration:

[Athletic training] means investing a lot of hard work and not always getting the kind of return on your investment that you had hoped. It means long hours and short pay. It means being part of a community effort to reach certain goals. It means witnessing the gamut of emotions that people go through from the “thrill of victory” to the “agony of defeat.” It means sharing all of those emotions with the athletes and yet sometimes not being able to express yourself completely [to the administration].

DISCUSSION

The aim of this investigation was to gain insight into the professional socialization influences and experiences of ATs working in the NCAA Division I setting. The data indicate that the participants in this study are heavily influenced by the bureaucratic aspects of the NCAA Division I athletic organizations in which they work, and the participants were extremely concerned about their diminished quality of life that may result from being an AT in this context. However, it appears that they maintain a commitment to delivering quality care to the student-athletes. In short, the ATs are able to care in the face of bureaucracy.

Organizational Influences

Many of the participants in the current study expressed concern with the organizations in which they worked and were seemingly surprised by the extent to which bureaucratic influences prevailed. Varying levels of bureaucracy permeate almost every organizational setting and thus should be expected to some extent. Indeed, the modern sport organization, such as college athletics, has been characterized as a highly commercialized bureaucracy. 11 Although bureaucracies come in various degrees, the dimensions of bureaucracy include a hierarchy of authority, a division of labor, organizational control, organizationally defined techniques, impersonality, and organizationally defined standards. 12 13

Bureaucratic influences have the propensity to create routinization of work and managerial control, increase volume of work, and downgrade job-related tasks and skill levels. 14 The participants experienced several of these aspects, including increased work volume, impersonality (lack of support and appreciation by administration), and a hierarchy of authority. According to Hummel, 15 bureaucracies promote efficiency and administrative control and may also give rise to inhumanity. Furthermore, referring to individuals working within a bureaucratic network, Hummel 15 stated that professionals may come to value efficiency at the cost of human decency, which might have significant consequences for allied health providers working in any context.

The organizational influences on the ATs, however, appeared not to have diminished their level of commitment toward the athletes they served. In fact, commitment to the student-athletes was evident with each participant. The ATs' level of commitment demonstrated to the student athletes corroborates findings from the study by Winterstein 4 about organizational commitment among collegiate head ATs. After surveying 461 head ATs regarding their work-environment commitments, he found that both student athletes and athletic training students were the primary objects of commitment among the participants in the study. Also consistent with the findings presented in the current study, Malasarn et al 16 found that expert male ATs were dedicated to the student-athletes and, indeed, part of their success in the NCAA Division I work environment was traced to their concern for the well-being of the athletes.

All but 1 of the ATs had previous experience as a graduate assistant athletic trainer in the NCAA Division I setting. Although work as a graduate assistant in this setting is often a rite of passage for obtaining a full-time position in this environment, 5 many participants in the current study expressed their concern with the organizations in which they worked, and few were initially prepared for such stressful environments. Davis 17 reported that few health care providers anticipate, or prepare for, the tremendous stress inherent in the helping professions. Cooper 18 explained that a great deal of occupational stress is related to the organizational structure and climate, such as high workload and low administrative support. Some participants in the current study, for example, identified instances of low administrative support, such as athletic directors not allocating appropriate resources (ie, equipment and additional staff) to enhance the health care delivery to the athletes. Also, some ATs felt as though they were low in the organizational hierarchy. These aspects of the organizations seemed to contribute to concerns related to the participants' quality of life.

Quality-of-Life Issues

Quality of life was a concern for the participants, particularly because they felt overloaded in their role and unappreciated by the administration. The information gained from the participants revealed organizational influences that resulted in high demands, low control over one's organizational structure, and low perceived administrative support. Such work environment factors are shown to contribute to role stress and strain 19 and even lead to burnout among allied health professionals.

In an investigation of the psychological and organizational factors related to burnout in ATs, Capel 20 found a relationship between the number of hours in direct contact with the athletes each week and burnout. This creates an interesting paradox in that the ATs in the present study tended to focus on dedicating themselves to the health and well-being of the athlete, yet the number of hours in direct contact with athletes is related to burnout. Furthermore, Hendrix et al 21 suggested that emotional exhaustion can occur because ATs can develop close relationships and become emotionally involved in the athletes' lives, thus leading to burnout.

As a result of burnout, many health care providers develop boundaries between their personal and professional lives, creating identifiable compartments. 17 That is, individuals attempt to separate their work roles, family roles, and friendship roles. In so doing, they feel torn between the various roles, creating competition within themselves. Similarly, as a result of role-related stress, it is not unusual for an individual to identify one aspect or part of a given role as dominant and de-emphasize the others. 22 This may well explain the participants' level of commitment toward the student-athletes.

The quality-of-life issues expressed by the participants, specifically a concern with burnout among collegiate ATs, has recently gained attention. 21 Indicating that life as an allied health care provider can be stressful and lead to burnout, Balogun et al 23 suggested that support from supervisors and colleagues were 2 critical factors to minimize stress. Clearly, an organization's culture can significantly affect an individual's work life.

An organization's culture and structure can influence the wellness of the professionals employed. Hamil 24 reported that bureaucratic structures, lack of empowerment, and organizational climates that do not adequately reward professionals promote a depreciated level of wellness. Bureaucratic organizations, according to Wilensky, 3 can strip a professional of autonomy and create barriers for professional development. This concept is also supported by Hamil, 24 who believed that the occupational dimensions of health and wellness, which includes balancing career and personal life and internal and external career rewards, are inextricably linked to an ability to continually learn and develop professionally.

The lack of administrative support identified by the participants in this study is not unique to ATs in the collegiate setting. When examining the experiences of clinical nurse specialists, Bousfield 25 found that a lack of support was a deterrent to successfully completing the participants' roles. Organizational support is crucial for job success; in fact, a lack of support can have a negative effect on health care providers. 25 As demonstrated in the aforementioned findings, the negative effect can be a diminished quality of life. Because such influences can affect practitioners, strategies to mitigate the negative aspects of these influences should be explored.

Implications

The results of this study indicate that the bureaucracy of the NCAA Division I setting can raise concerns about the ATs quality of life. Therefore, strategies must be explored that will allow ATs to effectively deal with the bureaucratic aspects and ameliorate the concerns related to stress and burnout within the organizations. The use of stress management, conflict resolution, mentoring strategies, continuing education, and critical reflection related to one's experiences may offer substantial promise to mitigate the negative organizational influences and manage quality-of-life issues.

To the extent that stress and strain are factors related to the quality-of-life issues expressed by ATs, stress management strategies may help address this problem. Organizational leaders and human resource personnel should consider implementing conflict resolution and stress management training. Such training may be warranted when ATs are initially inducted into their roles in an organization. Another induction strategy is to utilize mentors to learn an organization's structure and function.

Receiving direction from a mentor has been identified as a critical factor in becoming an expert male AT working in the collegiate setting. 16 Because mentoring can play a role in enhancing an individual's career development, ATs should also consider finding a mentor while working in this setting. In educational settings, Parkay et al 26 have suggested that individuals can benefit from interactions with others in similar roles. Indeed, being mentored by those who have successfully navigated the political work environments can potentially mitigate the bureaucratic influences and enhance the quality of life for those working in the NCAA Division I setting.

Hamil 24 recommended continuing education as a vehicle to facilitate a balance between personal and professional lives. Continued learning that facilitates workplace empowerment 27 may both effectively offset the barriers of professional development found in the workplace and enhance an AT's ability to continually grow and help gain a sense of occupational stability that supports his or her personal and professional lives.

Continued learning for these purposes should focus on fostering reflection. Reflection can facilitate not only improved occupational performance but also improved self-awareness and understanding. 28–30 Tang and Cheung 31 concluded that reflection is well suited to respond to the challenges of ever-changing professional environments not unlike those found in the health professions, including the work environment of ATs in the collegiate setting. Perhaps explicitly engaging professionals in reflective activities during the continuing education process can help develop these important skills.

The concept of reflection in professional fields is based on the idea that it facilitates self-understanding as it is connected to practice and that it can facilitate critical and creative thinking. 32 These qualities are especially helpful when experiencing indeterminate zones of practice, such as those created in the collegiate environment. Continuing education can play a crucial role in helping professionals integrate reflection and practice, stimulate an awareness of their own practice, and obtain an understanding of how professional action can shape the lives of citizens in our societies. 33

On a much more basic level, undergraduate students who seek employment in similar work settings would be well served to perform an internship in this setting, shadow an athletic director, or interview a collegiate staff member about his or her greatest challenges working in competitive environments. Moreover, introducing students to conflict management, stress management, and life skills training may help prepare them for dealing with the quality-of-life issues that arise in similar work settings. Recent researchers 34 have also found that ATs in dual positions (teaching and athletic training) in the high school setting who experienced low levels of role strain tended to negotiate or clarify their role. This role clarification often involved educating coaches about the extent of the AT's role as well as “saying no” to many additional responsibilities. Perhaps such strategies will also work in the collegiate setting.

Limitations

The results from this study may not be generalizable to all settings, although they may be transferable to similar Division I contexts. Because the participants identified volume of work as an organizational influence, more in-depth information related to work volume might have helped clarify some of the findings presented here.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, I investigated how ATs experience their role in the NCAA Division I setting. The role appears not only rewarding but also challenging. The reward is working closely with patients and developing an interpersonal bond; the challenge is dealing with a bureaucratic structure and balancing one's professional and personal lives to prevent burnout. Thought should be given to using stress management, role conflict, and time management strategies as well as mentoring processes to deal with these aspects related to the AT's role and to facilitating professional development in similar settings. Continuing education may be a promising way to promote reflection and empowerment in the work environment and mitigate negative organizational influences that may diminish one's quality of life.

To further explore organizational influences and quality-of-life issues in this context, future researchers could examine gender differences, years of experience, and workload influences. Additionally, investigations comparing how individuals are socialized into other organizations, such as different levels of organized athletics (ie, different NCAA levels), may lead to further understanding and insight. Moreover, research that examines factors facilitating commitment and enthusiasm in the work environment might be particularly revealing.

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr Paul Ilsley and Dr Jan Rintala for their insight and assistance during the course of this study.

Appendix 1. Semistructured Interview Guide

Appendix 2. Electronic Interview Questions

REFERENCES

- McPherson BD. Socialization into and through sport involvement. In: Luschen GRF, Sage GH, eds. Handbook of Social Science of Sport. Champaign, IL: Stipes; 1981:246–273 .

- Purtilo R. Foreword. In: Davis CM, ed. Patient Practitioner Interaction: An Experiential Manual for Developing the Art of Healthcare. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1998:xvii–xviii .

- Wilensky HL. The professionalization of everyone? Am J Sociol. 1964;70:137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Winterstein AP. Organizational commitment among intercollegiate athletic trainers: examining our work environment. J Athl Train. 1998;33:54–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitney WA, Ilsley P, Rintala J. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I context. J Athl Train. 2002;37:63–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JA. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996.

- Graber KC. The emergence of faculty consensus concerning teacher education: the socialization process of creating and sustaining faculty agreement. J Teach Phys Educ. 1993;12:424–436. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998.

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998.

- Chenitz WC, Swanson JM. Qualitative research using grounded theory. In: Chenitz WC, Swanson JM, eds. From Practice to Grounded Theory. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley; 1986:3–15 .

- Hall RH. The concept of bureaucracy: an empirical assessment. Am J Sociol. 1963;69:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon HL, Frey JH. A Sociology of Sport. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 1996.

- Hall RH. Professionalization and bureaucratization. Am Sociol Rev. 1968;33:92–104. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald D. The role of proletarianization in physical education teacher attrition. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1995;66:129–141. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1995.10762220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel R. The Bureaucratic Experience: A Critique of Life in the Modern Organization. New York, NY: St Martin's; 1994.

- Malasarn R, Bloom GA, Crumpton R. The development of expert male National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2002;37:55–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CM. Stress management. In: Patient Practitioner Interaction: An Experiential Manual for Developing the Art of Health Care. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1998:279–289 .

- Cooper CL. The experience and management of stress: job and organizational determinants. In: Riley AW, Zaccaro SJ, eds. Occupational Stress and Organizational Effectiveness. New York, NY: Praeger; 1987:53–70 .

- Lambert VA, Lambert CE. Literature review of role stress/strain on nurses: an international perspective. Nurs Health Sci. 2001;3:161–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2001.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capel SA. Psychological and organizational factors related to burnout in athletic trainers. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1986;57:321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix AE, Acevedo EO, Herbert E. An examination of stress and burnout in certified athletic trainers at Division I-A universities. J Athl Train. 2000;35:139–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage G. The social world of high school athletic coaches: multiple role demands and their consequences. Sociol Sport J. 1987;4:213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Balogun JA, Titiloye V, Balogun A, Oyeyemi A, Katz J. Prevalence and determinants of burnout among physical and occupational therapists. J Allied Health. 2002;31:131–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamil M. Wellness for professionals. In: Young WH, ed. Continuing Professional Education in Transition: Visions for the Professions and New Strategies for Lifelong Learning. Malabar, FL: Krieger; 1998:21–41 .

- Bousfield C. A phenomenological investigation into the role of the clinical nurse specialist. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:245–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkay FW, Currie GD, Rhodes JW. Professional socialization: a longitudinal study of first-time high school principals. Educ Admin Q. 1992;28:43–75. [Google Scholar]

- Flagello JR. Continuing education for the professions: the catalyst for workplace empowerment. In: Young WH, ed. Continuing Professional Education in Transition: Visions for the Professions and New Strategies for Lifelong Learning. Malabar, FL: Krieger; 1998:43–57 .

- Marsick VJ, Watkins KE. Continuous learning in the workplace. Adult Learn. 1992;3:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Marsick VJ. Sculpting the Learning Organization: Lessons in the Art and Science of Systemic Change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1993.

- Redding JC, Catalanello RF. Strategic Readiness: The Making of the Learning Organization. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1994.

- Tang K, Cheung JT. Models of workplace training in North America: a review. Int J Lifelong Educ. 1996;15:256–265. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan JM, Chernomas WM. Developing the reflective teacher. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:1138–1143. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forester J. Planning in the Face of Power. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1989.

- Pitney WA, Stuart ME, Parker J. The prevalence of role strain among dual position physical educators and certified athletic trainers in the high school setting. Paper presented at: The Illinois Association for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance Convention; November 18, 2005; St Charles, IL.