Abstract

Context: Sport training enhances the ability to use somatosensory and otolithic information, which improves postural capabilities. Postural changes are different according to the sport practiced, but few authors have analyzed subjects' postural performances to discriminate the expertise level among highly skilled athletes within a specific discipline.

Objective: To compare the postural performance and the postural strategy between soccer players at different levels of competition (national and regional).

Design: Repeated measures with 1 between-groups factor (level of competition: national or regional) and 1 within-groups factor (vision: eyes open or eyes closed). Dependent variables were center-of-pressure surface area and velocity; total spectral energy; and percentage of low-, medium-, and high-frequency band.

Setting: Sports performance laboratory.

Patients or Other Participants: Fifteen national male soccer players (age = 24 ± 3 years, height = 179 ± 5 cm, mass = 72 ± 3 kg) and 15 regional male soccer players (age = 23 ± 3 years, height = 174 ± 4 cm, mass = 68 ± 5 kg) participated in the study.

Intervention(s): The subjects performed posturographic tests with eyes open and closed.

Main Outcome Measure(s): While subjects performed static and dynamic posturographic tests, we measured the center of foot pressure on a force platform. Spatiotemporal center-of-pressure measurements were used to evaluate the postural performance, and a frequency analysis of the center-of-pressure excursions (fast Fourier transform) was conducted to estimate the postural strategy.

Results: Within a laboratory task, national soccer players produced better postural performances than regional players and had a different postural strategy. The national players were more stable than the regional players and used proprioception and vision information differently.

Conclusions: In the test conditions specific to playing soccer, level of playing experience influenced postural control performance measures and strategies.

Keywords: balance, soccer, postural control, spectral analysis

Postural regulation is organized in hierarchic and stereotypic patterns 1 and requires the integration of afferent information from the visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive systems. 2 Sport training enhances the ability to use somatosensory and otolithic information, which improves postural capabilities. 3 Postural changes are different according to the sport practiced. 4 For example, judo training leads to greater importance being placed on somatosensory information, whereas dance training results in more attention to visual information. 5 Each sport develops specific postural adaptations that are not transferable to the usual upright postures. 6 7 Indeed, Asseman et al 6 evaluated elite gymnasts in 3 postural conditions: bipedal, unipedal, and handstands. The gymnasts who were best in the specific unipedal or handstand conditions were not the same as those who were best in the nonspecific bipedal task. Even though nonspecific tasks such as bipedal stance are typically used in activities of daily living, in athletes, it is more relevant to evaluate postural abilities in specific conditions relative to the particular sport.

Soccer requires a unipedal posture to perform different technical movements (eg, shooting, passing). The stability of the supporting foot turns out to be critical to shoot as accurately as possible. Therefore, soccer players' postural control should be evaluated in a unipedal stance to respect the specific conditions of soccer. Previous authors have studied soccer players' postural control in a unipedal stance to reduce the risk of traumatic injuries to the lower extremities 8 or to evaluate the effects of rehabilitative training of the ankle joint. 9 10 However, as far as we know, no study has yet been carried out comparing postural performance and strategy in soccer players of different levels of expertise. The postural performance can be characterized by the ability to minimize postural sway, and the postural strategy corresponds to the preferential involvement of short or long neuronal loops in balance regulation. Our aim was to compare postural performance and strategy in unipedal stance between players at different levels of soccer competition.

METHODS

Subjects

Two groups of 15 male soccer players aged 18 to 30 years participated in the study. One group was composed of 15 soccer players who played at the national level (NAT) (age = 24 ± 3 years, height = 179 ± 5 cm, mass = 72 ± 3 kg). The other group was composed of 15 players at the regional level (REG) (age = 23 ± 3 years, height = 174 ± 4 cm, mass = 68 ± 5 kg). The NAT and REG players had played soccer for 13 ± 2 and 10 ± 3 years, respectively. None had stopped playing for more than 3 weeks during the 6 months before the study because of ankle, knee, hip, or other known injuries. The NAT players trained almost every day and the REG players trained twice a week. We conducted the experiment in the middle of the competitive season. The subjects signed an informed consent as required by the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Measurements

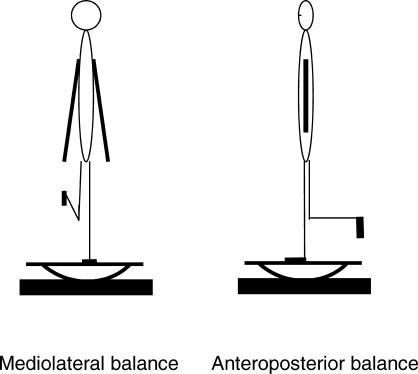

We asked the subjects to stand as still as possible with their arms along the body on 1 leg on a force platform (PostureWin, Techno Concept, Cereste, France; 40-Hz frequency, 12-bits A/ D conversion) that recorded the displacements of the center of foot pressure (COP) with 3 strain gauges. When the subject's right leg was dominant for kicking the ball, then the left leg was the supporting leg (conversely, when the subject's left leg was dominant, the right leg was supporting). The foot was placed according to precise landmarks with respect to the X and Y axes of the platform. The other leg was raised and flexed 90° at the knee. The hips were placed in a neutral position (0° of flexion). Three conditions of balance were tested first with eyes open (EO) and then with eyes closed (EC): a static balance condition on stable ground and 2 dynamic balance conditions on a seesaw device (Stabilomètre; Techno Concept) that generated instability ( Figure 1) in the anteroposterior or the mediolateral direction (anteroposterior or mediolateral dynamic balance). In the EO condition, the subjects looked at a fixed level target at a distance of 2 m. In the EC condition, they were asked to keep their gaze in a straight-ahead direction. The test lasted 51.2 seconds in the static balance condition and 25.6 seconds in the dynamic balance condition. The subjects could lightly touch the seesaw with the raised leg in the dynamic balance condition, and only the total loss of balance invalidated the trial.

Figure 1. The seesaw (Stabilomètre) device is laid on the force platform (full rectangle). This device has only 1 degree of free motion.

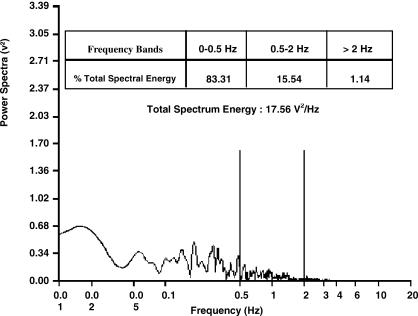

The COP signals were smoothed using a second-order Butterworth filter with a 6-Hz low-pass cut-off frequency. The COP surface area (90% confidence ellipse) evaluates the subject's postural performance: the smaller the area, the better the performance. 11 The COP velocity (sum of the accumulated COP displacement divided by the total time) evaluates the subject's postural control. 6 11 The COP excursions were also investigated in the frequency domain to assess the preferential involvement of short or long neuronal loops in balance regulation. 12–17 Fast Fourier transforms were applied to COP displacements from 0 to 20 Hz. Hence, the total spectral energy was calculated and distributed in 3 frequency bands ( Figure 2): low frequencies, 0 to 0.5 Hz; medium frequencies, 0.5 to 2 Hz; and high frequencies, greater than 2 Hz. 18 19 The values of these 3 frequency bands were expressed as a percentage of the spectral energy. Low frequencies mostly account for visuovestibular regulation, 20 21 medium frequencies for cerebellar regulation, 22 and high frequencies for proprioceptive regulation. 12 21 23

Figure 2. Fast Fourier transform analysis of center-of-pressure displacement of a subject in the mediolateral dynamic balance condition.

Statistical Analysis

Each condition of balance (static balance, anteroposterior or mediolateral dynamic balance) was independently analyzed. The data analysis was performed with a 2-way analysis of variance with 1 between-groups factor (2 levels of competition, NAT and REG) and 1 within-groups factor with repeated measures (2 levels of vision, EO and EC). Dependent variables were COP surface area, COP velocity, total spectral energy, percentage of low-frequency band, percentage of medium-frequency band, and percentage of high-frequency band. This analysis of variance also highlights possible interactions between these 2 factors (group and vision). We calculated the Fisher F value and selected P < .05 as the level of significance.

RESULTS

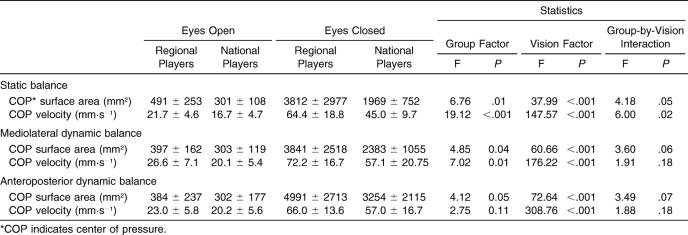

In the static balance condition and the mediolateral dynamic balance condition, the COP surface area and COP velocity were significantly greater for REG soccer players than for NAT soccer players ( Table). In the anteroposterior dynamic balance condition, only the COP surface area was significantly greater for REG soccer players than for NAT soccer players. For both NAT and REG, the suppression of vision significantly increased the COP surface area and COP velocity in the static and both dynamic balance conditions (see Table). In the dynamic balance conditions, we noted no significant vision-by-group interaction. Nevertheless, the vision-by-group interaction was significant in the static balance condition for COP surface area and COP velocity.

Postural Variables in the Regional (n = 15) and National (n = 15) Soccer Players with Eyes Open and Closed (Mean ± SD).

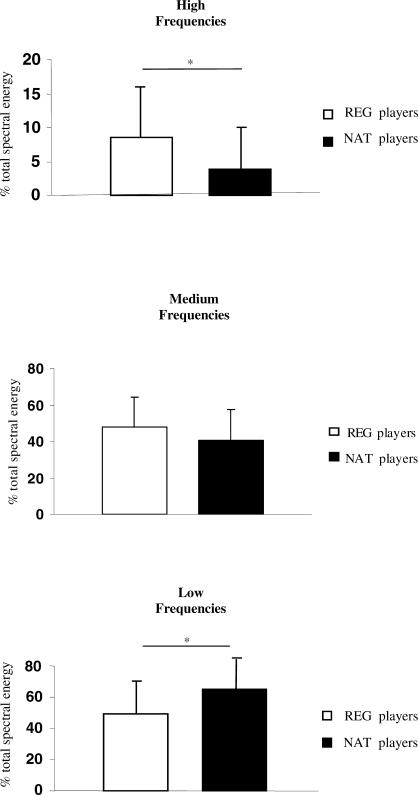

Moreover, in the static balance condition, neither the total spectral energy nor the relative contribution of each of the 3 frequency bands was significantly different between REG and NAT players. In the mediolateral dynamic balance condition, the total spectral energy was greater for REG players than for NAT players (EO: 57504 ± 35775 V 2 versus 34187 ± 17301 V 2, respectively; EC: 71683 ± 41596 V 2 versus 38336 ± 35643 V 2, respectively; F 1,28 = 6.04, P = .02). For anteroposterior dynamic balance, the total spectral energy was not significantly different between the groups. When focusing on the relative contribution of the 3 frequency bands, we found that the high and low frequencies were significantly different between the groups in the anteroposterior dynamic balance condition ( Figure 3). The contribution of the high frequencies was less in NAT players than REG players. By contrast, the contribution of low frequencies was greater in NAT players than REG players. In the mediolateral dynamic condition, no significant difference was seen between the groups in relation to the contributions of the 3 frequency bands.

Figure 3. Percentage of total spectral energy in the anteroposterior dynamic balance condition. Top, High-frequency band. Middle, Medium-frequency band. Bottom, Low-frequency band. *Indicates a significant difference, P < .05. REG indicates regional players; NAT, national players .

DISCUSSION

In both the static and dynamic balance conditions, the COP surface area was greater for REG soccer players than for NAT soccer players. Based on the findings of Caron et al, 11 NAT soccer players produced the best postural performance. Moreover, the COP velocity was greater in REG players than in NAT players. Thus, NAT players' postural control was better than that of REG players, 6 suggesting that NAT players possessed a greater sensitivity of sensory receptors or better integration of information than REG players (or both). 24 Similar results were reported by Era et al, 25 who showed that international-level rifle shooters were more stable than national-level shooters. Nevertheless, Paillard et al 26 reported no relationship between competition level and postural control in judo athletes because the subjects were not evaluated in a condition specific to judo. In our study, balance was evaluated in a postural condition close to that of soccer (unipedal stance). Our results suggest that one can discriminate the level of performance in soccer when balance is evaluated in a condition close to that of the sport. However, training is more frequent among NAT soccer players than REG soccer players (daily versus biweekly training, respectively). Certainly, a relationship between the competition level and postural abilities was shown, but one could ask whether the performance level (competition level) influenced the postural abilities by intrinsic qualities (natural predispositions) or the amount of training influenced the postural abilities by some motor program acquisitions that included specific postural adaptations.

Moreover, the total spectral energy in mediolateral dynamic balance was greater for REG players than for NAT players. According to Dichgans et al, 20 the contribution of afferent information (ie, somatosensory, vestibular, and visual) is more important for REG players than for NAT players to regulate mediolateral balance. Because differences in the total spectral energy only affect lateral dynamic balance, one could hypothesize that soccer is a dynamic activity predominantly requiring fine postural control in the frontal plane. Similarly, the contribution of the high and low frequencies was different between the groups in anteroposterior dynamic balance. In the sagittal plane, the NAT players used a greater proportion of energy in the low-frequency band, contrary to REG players, who used a greater proportion of energy in the high-frequency band. According to other authors, 18 19 23 these results suggest different postural strategies between the groups. Indeed, during simple unipedal tasks of balance (static and dynamic balance), REG players proportionally use more short-loop information (proprioceptive myotactic and plantar cutaneous) than NAT players. Moreover, NAT players proportionally use more long-loop (vestibular) information and, thus, probably have more efficient vestibular or interoceptive (or both) input than REG players. Bringoux et al 3 reported similar findings in gymnasts, showing that the efficiency of otolithic and/or interoceptive inputs improved with increasing sport expertise. Therefore, this greater efficiency of the vestibular system would enable NAT players to regulate simple postural tasks without overusing proprioception. Conversely, REG players, when using proprioception in a dominant way during simple tasks (such as those in our protocol) would saturate the proprioceptive system more quickly as the difficulty of the postural task increased. Indeed, with a more complex postural task (eg, in soccer, control of the ball in the air on 1 leg), which necessarily requires stimulation of short neural loops, 27 only NAT players could initially select and use proprioceptive information to efficiently regulate their posture.

Equally, when the visual information was suppressed, COP surface area increased and COP velocity decreased in the 3 conditions (static and dynamic balance conditions). As has already been shown by other authors in judo and karate athletes, dancers, and gymnasts, 7 14 28 29 visual information is a determining factor in the postural regulation of soccer players. Moreover, the vision-by-group interaction for COP surface area and COP velocity was significant in static balance. For anteroposterior and mediolateral dynamic balance, this interaction was not significant, but tendencies were strong (surface area: P = .07 and P = .06, respectively). Therefore, REG players are probably more dependent on vision than NAT players. The NAT players would have a better internal representation of erect posture (including the role played by the various sensory inputs in this representation), which probably provides a better knowledge of the body axis and verticality than REG players. Nevertheless, other protocols using different visual conditions (eg, reduction in visual field, visual manipulation) would allow confirmation of this phenomenon.

CONCLUSIONS

Postural performance and strategy were different between NAT and REG soccer players. In test conditions specific to playing soccer, level of playing experience appears to influence postural control performance measures and strategies. In conditions specific to the playing of soccer, postural capabilities can be considered as one criterion of performance or ability.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Boschat from Techno Concept (Cereste, France) for having kindly lent us the force platform.

REFERENCES

- Horak FB, Nashner LM. Central programming of postural movement: adaptation to altered support-surface configurations. J Neurophysiol. 1986;55:1369–1381. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.6.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massion J. Postural control systems in developmental perspective. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1998;22:465–472. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(97)00031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringoux L, Marin V, Nougier V, Barraud PA., Raphel C. Effects of gymnastics expertise on the perception of body orientation in the pitch dimension. J Vestib Res. 2000;10:251–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davlin CD. Dynamic balance in high level athletes. Percept Mot Skills. 2004;98:1171–1176. doi: 10.2466/pms.98.3c.1171-1176. (3 pt 2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin P, Deviterne D, Hugel F, Perrot C. Judo, better than dance, develops sensorimotor adaptabilities involved in balance control. Gait Posture. 2002;15:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(01)00149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asseman F, Caron O, Crémieux J. Is there a transfer of postural ability from specific to unspecific postures in elite gymnasts? Neurosci Lett. 2004;358:83–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugel F, Cadopi M, Kohler F, Perrin P. Postural control of ballet dancers: a specific use of visual input for artistic purposes. Int J Sports Med. 1999;20:86–92. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderman K, Werner S, Pietila T, Engstrom B, Alfredson H. Balance board training: prevention of traumatic injuries of the lower extremities in female soccer players? A prospective randomized intervention study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:356–363. doi: 10.1007/s001670000147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauffin H, Tropp H, Odenrick P. Effect of ankle disk training on postural control in patients with functional instability of the ankle joint. Int J Sports Med. 1988;2:141–144. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintsaar A, Brynhildsen J, Tropp H. Postural corrections after standardised perturbations of single limb stance: effect of training and orthotic devices in patients with ankle instability. Br J Sports Med. 1996;30:151–155. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.30.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron O, Gelat T, Rougier P, Blanchi JP. A comparative analysis of the center of gravity and centre of pressure trajectory path lengths in standing posture: an estimation of active stiffness. J Appl Biomech. 2000;16:234–247. doi: 10.1123/jab.16.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V, Mauritz KH, Dichgans J. Body oscillations in balancing due to segmental stretch reflex activity. Exp Brain Res. 1980;40:89–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00236666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick R, Rogers DK, McCloskey DI. Stable human standing with lower-limb muscle afferents providing the only sensory input. J Physiol. 1994;480:395–403. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020369. (pt 2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golomer E, Cremieux J, Dupui P, Isableu B, Ohlmann T. Visual contribution to self-induced body sway frequencies and visual perception of male professional dancers. Neurosci Lett. 1999;267:189–192. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00356-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitton D, Kearney RE, Wereley N, Peterson BW. Visual, vestibular and voluntary contributions to human head stabilization. Exp Brain Res. 1986;64:59–69. doi: 10.1007/BF00238201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki BE. Selection of perturbation parameters for identification of the posture-control system. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1986;24:561–568. doi: 10.1007/BF02446257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterka RJ. Sensorimotor integration in human postural control. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1097–1118. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golomer E, Dupui P, Bessou P. Spectral frequency analysis of dynamic balance in healthy and injured athletes. Arch Int Physiol Biochim Biophys. 1994;102:225–229. doi: 10.3109/13813459409007543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golomer E, Dupui P. Spectral analysis of adult dancers' sways: sex and interaction vision-proprioception. Int J Neurosci. 2000;105:15–26. doi: 10.3109/00207450009003262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichgans J, Mauritz KH, Allum JH, Brandt T. Postural sway in normals and atactic patients: analysis of the stabilising and destabilizing effects of vision. Agressologie. 1976;17:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy E, Toth K, Janositz G. Postural control in athletes participating in an ironman triathlon. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;92:407–413. doi: 10.1007/s00421-004-1157-7. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njiokiktjien C, De Rijke W, Dieker-Van Ophem A, Voorhoeve-Coebergh O. A possible contribution of stabilography to the differential diagnosis of cerebellar processes. Agressologie. 1978;19:87–88. (B) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurfinkel VS. Muscle afferentation and postural control in man. Agressologie. 1973;14:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuillerme N, Teasdale N, Nougier V. The effect of expertise in gymnastics on proprioceptive sensory integration in human subjects. Neurosci Lett. 2001;311:73–76. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Era P, Konttinen N, Mehto P, Saarela P, Lyytinen H. Postural stability and skilled performance: a study on top-level and naive rifle shooters. J Biomech. 1996;29:301–306. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paillard T, Costes-Salon MC, Lafont C, Dupui P. Are there differences in postural regulation according to the level of competition in judoists? Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:304–305. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.4.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashner LM. Fixed patterns of rapid postural responses among leg muscles during stance. Exp Brain Res. 1977;30:13–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00237855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin P, Schneider D, Deviterne D, Perrot C, Constantinescu L. Training improves the adaptation to changing visual conditions in maintaining human posture control in a test of sinusoidal oscillation of the support. Neurosci Lett. 1998;245:155–158. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuillerme N, Danion F, Marin L. The effect of expertise in gymnastics on postural control. Neurosci Lett. 2001;303:83–86. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01722-0. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]