Abstract

Objectives: To quantify the number of doctors charged with manslaughter in the course of legitimate medical practice and to classify cases, as mistakes, slips (or lapses), and violations, using a recognized classification of human error system.

Design: We searched newspaper databases, Medline, Embase, and the Wellcome library catalogue to identify relevant cases from 1795 to December 2005.

Setting: Medical practice in the United Kingdom.

Main outcome measure: Number of doctors charged with manslaughter in the course of medical practice.

Results: We identified 85 doctors charged with manslaughter since 1795. The number of doctors charged was relatively high in the mid-19th century and the inter-war years, and has dramatically increased since 1990. Sixty of the doctors were acquitted, 22 were convicted, and three pleaded guilty. Most doctors were charged as a consequence of mistakes (37) or slips (17), and a minority because of alleged violations (16).

Conclusions: The number of doctors prosecuted for manslaughter has risen steeply since 1990, but the proportion of doctors convicted remains low. Prosecution for deliberately violating rules is understandable, but accounts for only a minority of these cases. Unconscious errors—mistakes and slips (or lapses)—are an inescapable consequence of human actions and prosecution of individuals is unlikely to improve patient safety. That requires improvement to the complex systems of health care.

INTRODUCTION

Medical errors have serious consequences.1 Between 44 000 and 98 000 patients may die every year in US hospitals from preventable errors in their care.2 When a death occurs as a result of such an error, the desire to attribute blame can lead to criminal proceedings; the 1990s saw a marked increase in the number of doctors charged with manslaughter.3,4 We have examined British data on doctors charged with manslaughter in the course of medical practice from the early 19th century to the present day.

SEARCH STRATEGY

We searched The Times Digital Archive (1795-1985), The Scotsman Digital Archive (1817-1950), and the Lexis Nexis (1985-December 2005) databases using the text words doctor, anaesthetist, or surgeon and manslaughter, to identify relevant newspaper articles and case law reports. We also searched Medline (1955-December 2005) and Embase (1974-December 2005) using the text word manslaughter. In addition, we searched the titles and abstracts of the Lancet (1823-December 2005) electronically using the text words manslaughter, assizes, criminal court, or verdict. Finally, we carried out a search of the Wellcome library catalogue using the search term manslaughter. Where information on potentially relevant cases was incomplete, we also hand searched the indexes of the Lancet and the BMJ for the year during which a case was tried. A previous article5 was limited to errors in administering anaesthetics or prescribing or giving medicines in the years 1970-1999. Here we extend the search to include all medical practitioners charged with manslaughter from 1795-2005. We divided the cases we identified, according to a recognized classification of human error,6,7 as mistakes, slips or lapses, and violations.

RESULTS

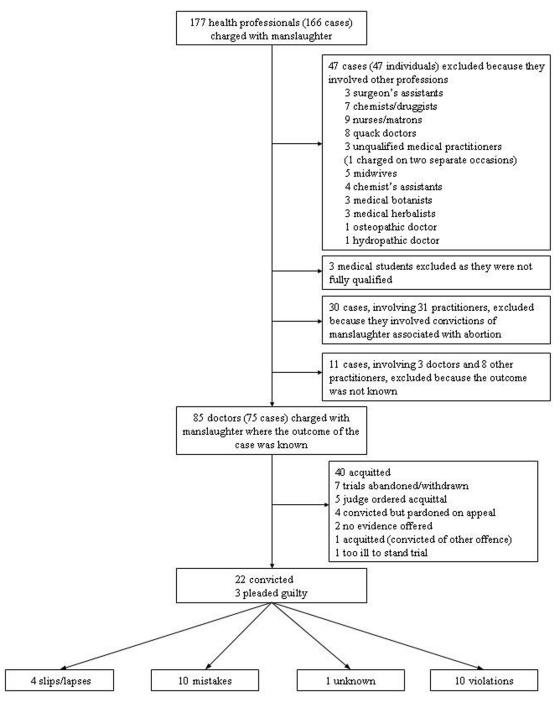

We initially identified 177 health professionals charged with manslaughter. Forty-seven individuals were not medically qualified. Three medical students, who were practicing as fully qualified doctors, even though they had not obtained the legal qualifications were also excluded from the analysis. Thirty-one practitioners were accused of manslaughter associated with criminal abortion rather than errors during legitimate practice, and we also excluded them. The outcomes of the cases of three doctors could not be found, and are not reported here. Therefore 75 cases, involving 85 doctors, were identified in the period 1795-2005 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of search strategy

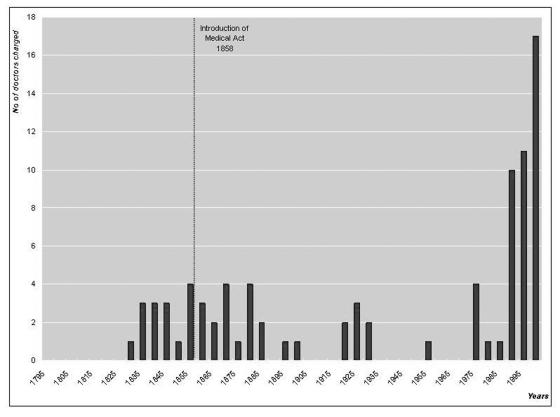

The number of doctors charged with manslaughter since 1795 was relatively high in the mid-19th century and the inter-war years, and has dramatically increased since 1990 (Figure 2). The majority of the cases from the 19th century related to obstetrics (19 of 32 cases), while most cases in the 20th century involved errors in the administration or prescribing of medicines (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Number of doctors charged with manslaughter as a result of the death of a patient, 1795 to 2005 (excluding abortion cases)

Table 1.

Number of doctors charged with manslaughter, by type of case

| Type of case | Total charged | From 1795-1899 | From 1900-2005 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obstetric care | 22 | 19 | 3 |

| Inappropriate treatment/Failure to diagnosis | 18 | 8 | 10 |

| Surgery | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Medicines | 36 | 5 | 31 |

| Total | 85 | 32 | 53 |

Sixty (71%) doctors charged with manslaughter were acquitted, with 22 doctors being convicted and three pleading guilty to the charge. Since 1975, 44 doctors have been charged, of whom 30 (68%) were acquitted and 14 pleaded guilty to or were convicted of manslaughter (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of doctors charged with and convicted of manslaughter

| Years | Total charged | Total convicted/pleaded guilty | Convicted |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1795-1824 | 0 | 0 | 0% |

| 1825-1854 | 11 | 4 | 36% |

| 1855-1884 | 18 | 4 | 22% |

| 1885-1914 | 4 | 1 | 25% |

| 1915-1944 | 7 | 1 | 14% |

| 1945-1974 | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| 1975-2005 | 44 | 14 | 32% |

| 1795-1899 | 32 | 9 | 28% |

| 1900-2005 | 53 | 16 | 30% |

The earliest case was of a Dr Raeburn, who in 1831 was charged with manslaughter following the death of a woman after childbirth.8

Doctors were most commonly charged with manslaughter as a result of mistakes (37/85 doctors), which are errors in the planning of an action. Ten of these doctors (27%) were convicted. The cases of 17 doctors were classified as slips, which are errors in the execution of an action that often occur as a result of distraction or momentary failure of concentration. Four of these doctors (24%) were convicted. There were also three cases that involved technical errors, which occur when there is a failure to carry out an action successfully even if the plan of action and technique are appropriate. Sixteen were classified as violations, in which there is a deliberate deviation from safe practices. Ten of these doctors (63%) were convicted. In 11 cases, involving 12 doctors, there was insufficient information to classify the case. Examples of cases that were classified are presented below.

Mistakes

Case 1 (1844)

A 6-week-old girl was prescribed a mixture containing two drops of laudanum [a tincture of opium] and died. The mixture contained four times the standard dose. The prescribing surgeon was charged with manslaughter but acquitted.9

Case 2 (1874)

A woman died from an overdose of morphia administered by her husband, a surgeon, to help her to sleep. He allegedly administered 17 grains (778 mg) of morphia over a 3-hour period. He was charged with manslaughter but acquitted.10

Case 3 (1999)

A general practitioner administered 30 mg of diamorphine to a 55-year-old man suffering from lower back pain. The patient died from respiratory failure. The maximum recommended initial dose of diamorphine is 10 mg. The GP was charged with manslaughter and convicted.11

Case 4 (2001)

A 20-year-old emaciated man with muscular dystrophy died after circumcision. The surgeon guessed the patient's weight and inadvertently gave three times the recommended dose of lidocaine. He was charged with manslaughter but acquitted.12

Slips and lapses

Case 5 (1867)

A woman was prescribed three tablespoons of medicine obtained from a doctor, which was supposed to contain bismuth, henbane, and quassia. In error, the medicine was made up with strychnine, not bismuth, and the woman died. The doctor was charged with manslaughter but acquitted.13

Case 6 (1978)

A 4-year-old boy who had had a brain tumour removed was given 650 mg of methotrexate into the cerebral ventricles, developed convulsions, and died. The dose of methotrexate was 20 times too great. The junior doctor who had given the injection had taken the dosage from the case notes, `... not knowing that it related only to intravenous drips'. She was charged with manslaughter but acquitted.14

Case 7 (2003)

An 18-year-old man with leukaemia was due to receive cytosine, to be injected intrathecally that day; and vincristine, to be injected intravenously the next day. The senior house officer correctly administered the cytosine, but the registrar then handed his junior the vincristine and told him to inject it into the patient's spine. Although the SHO checked twice to be certain of the registrar's instructions, he was told to go ahead with the injection. The registrar was charged with manslaughter and pleaded guilty.15

Case 8 (2004)

A 6-week-old boy died after cardiac arrest during surgery for pyloric stenosis. The anaesthetist injected air into the bloodstream instead of the nasogastric tube. The anaesthetist was charged with manslaughter but acquitted.16

Technical errors

Case 9 (1875)

A woman died during childbirth and the surgeon was charged with manslaughter due to alleged unskilful treatment. Following inquiries, it was found that the doctor followed a course of treatment that would have been followed by any skilful surgeon and the case was withdrawn.17

Case 10 (2001)

A 16-year-old girl being treated for leukaemia died after an attempt to insert a Hickman line (central venous catheter) caused cardiac rupture. The surgeon was charged with manslaughter but acquitted.18

Violations

Case 11 (1839)

A woman died following childbirth. The post mortem examination revealed injuries to the woman that had been caused by the unskilful and violent use of some instrument. The surgeon may have been intoxicated during the delivery and was charged with manslaughter, but acquitted.19

Case 12 (1859)

A woman died several days after an instrumental delivery, as the result of a large vaginal wound. It was alleged that the doctor had been `fresh' (drunk) and had been deficient of ordinary skill and caution, or had, by intoxication, rendered himself unfit. He was charged with manslaughter and found guilty.20

Case 13 (1959)

A 2-year-old boy died from hypoxia that occurred during a hernia operation. The anaesthetist had deliberately inhaled anaesthetic before and during the operation. He was charged with manslaughter and found guilty.21

Case 14 (2004)

A 71-year-old woman died after suffering catastrophic blood loss during surgery to remove a cancerous tumour from her liver. The surgeon admitted that he should not have continued the operation after finding that the tumour was twice the size he had expected, and was near important blood vessels. He was also alleged to have had his picture taken with her dissected liver during the operation. He was charged with manslaughter and other offences. He pleaded guilty to manslaughter.22

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE: THE CHARGE OF INVOLUNTARY MANSLAUGHTER OVER THE PAST TWO CENTURIES

We set out to identify qualified doctors, but the formal distinction between legally qualified and unqualified practitioners was not made until the Medical Act 1858. Before this, many patients used the services of unlicensed practitioners, of whom several were charged with manslaughter.

In the early 19th century, the law recognized that medical practitioners were not immune to human error; juries were directed to convict a practitioner only if the prosecution had proved that the individual owed the patient a duty of care, and had acted with gross want of skill and care. For example, in 1862 Frederick Robinson, a surgeon, was charged with the death of a woman following childbirth.23 Instead of removing the placenta, he had dragged out a portion of the intestines. The judge stated:

`Every medical man was of course liable to make a mistake, and he would not be criminally responsible for the consequences if it should appear that he had exercised reasonable skill and caution, and it was only in the case where a medical man, as he had before stated, was guilty of gross negligence, or evinced a gross want of knowledge of his profession, that he could be held criminally responsible.'

Robinson was convicted and imprisoned.

Unlicensed practitioners were held accountable by the law in a similar manner to licensed practitioners in the period before the Medical Act 1858. For example, in 1834, a chemist named Joseph Webb was charged following the death of patient to whom he had administered medicine for the treatment of smallpox.24 The judge in this case stated that:

`... in these cases there is no difference between a licensed physician or surgeon, and a person acting as a physician or surgeon without a licence. In either case, if a party having competent degree of skill and knowledge, makes an accidental mistake in his treatment of a patient, through which mistake death ensues, he is not thereby guilty of manslaughter: but if where proper medical assistance can be had, a person totally ignorant of the science of medicine takes upon himself to administer a violent and dangerous remedy to one labouring under a disease, and death ensues in consequence of this dangerous remedy having been so administered, then he is guilty of manslaughter.'

Webb was acquitted.

Judicial attitudes seem to have changed after the Medical Act 1858. In 1859, William Crick, a medical botanist was charged with causing the death of a child by giving a dose of Lobelia inflata (an emetic herb).25 The judge stated:

`If the prisoner had been a medical man I should have recommended you to take the most favourable view of his conduct, for it would be most fatal to the efficiency of the medical profession if no one could administer medicine without a halter round his neck.'

Crick was acquitted.

The law relating to involuntary manslaughter has been clarified by two medical cases. Dr Percy Bateman was convicted in 1925 of gross negligence manslaughter after a woman died following childbirth. During manual removal of the placenta, he had mistakenly removed a portion of the uterus. The Court of Criminal Appeal quashed his conviction, stating that to be convicted, the defendant's negligence must be `... so gross that it showed such a disregard for the life and safety of others as to amount to a crime against the state and conduct deserving punishment'.26

In 1995 the House of Lords considered the case of John Adomako, an anaesthetist, convicted of gross negligence manslaughter after the death of a patient following a cardiac arrest during surgery for a retinal detachment.27 The anaesthetist noticed hypoxia only when a blood pressure alarm sounded some 4½ min after the endotracheal tube became disconnected from the oxygen supply. The House of Lords held that gross negligence defined in the Bateman case was the appropriate test in manslaughter cases involving breach of duty.

DISCUSSION

We identified 85 doctors over the past two centuries who were charged with manslaughter due to medical errors. Leahy Taylor stated the earliest known case13 was tried in 1867.28 However, we identified several cases of licensed doctors, as well as unqualified practitioners, who were charged with manslaughter before this.

There were many cases in the middle of the 19th century, the majority related to obstetrics. This may be explained by the increasing medicalization of childbirth during that time. The 1800s saw increased, and often injudicious, use of forceps and a high rate of maternal mortality, which did not alter dramatically until the early 1940s.29 The introduction of powerful, sometimes dangerous, medicines in the 20th century, may also explain why the majority of cases from this period involved medicines.

Several cases involved drunkenness or brutal lack of skill, but many were classified as mistakes (errors in planning) or slips (errors in executing an action). Slips are inherent to human cognition and are more likely to occur when an individual is tired, distracted, or interrupted. They can only be prevented or minimized when the systems and processes in which doctors work are made safer. This is most likely to happen when practitioners are candid about their errors.30

The dramatic increase in the number of doctors charged with manslaughter over the past two decades is evident. However, the conviction rate remains at around 30%. In the UK, the

`... Crown Prosecutors must be satisfied that there is enough evidence to provide a “realistic prospect of conviction”... [that is] that a jury or a bench of magistrates, properly directed in accordance with the law, will be more likely than not to convict the defendant of the charge alleged.'31

The Crown Prosecution Service charges too many doctors, even by its own standards.

Limitations of our study

We may have failed to identify some relevant cases and we explicitly excluded non-qualified practitioners from the search strategy and analysis, which may have led to a biased representation of the early 19th century. The results are presented without consideration to the actual number of practising doctors or the number of interactions between doctor and patient. They therefore do not provide insight into the actual proportion of doctors charged with manslaughter or the proportion of patients whose death led to charges of manslaughter.

CONCLUSIONS

The criminal prosecution of a doctor is appropriate when there is clear evidence of violation of safety rules. However, human error is unavoidable in the course of care. Charging doctors with manslaughter following a medical error may be an emotionally satisfying way to exact retribution, but if individual doctors are singled out for punishment it will become much harder to foster an open culture. Faults in the system will remain hidden, and more patients will die.

Details of Funding Sarah E McDowell was supported by the Antidote Trust Fund of the Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust.

Competing interests RE Ferner has received fees for writing medicolegal reports. Sarah E McDowell has no competing interests.

References

- 1.An Organisation With a Memory. Report of an Expert Group on Learning From Adverse Events in The NHS Chaired By The Chief Medical Officer. Norwich. London: Stationery Office, 2000

- 2.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington: National Academy Press, 1999 [PubMed]

- 3.Dyer C. Doctors face trial for manslaughter as criminal charges against doctors continue to rise. BMJ 2002;325: 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holbrook J. The criminalisation of fatal medical mistakes. BMJ 2003; 327: 1118-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferner RE. Medication errors that have led to manslaughter charges. BMJ 2000;321: 1212-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reason J. Human Error. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990

- 7.Ferner RE, Aronson JK. Medication errors, worse than a crime. Lancet 2000;355: 947-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lent Assizes, York. The Times 31 March 1831: 4

- 9.Crown Side (Before the Lord Chief Baron). The Times 22 August 1844: 6

- 10.Spring Assizes, Northern Circuit, Carlisle. The Times 23 February 1874: 11

- 11.Manslaughter GP walks free. Daily Mail 3 August 1999: 2

- 12.Jury clears surgeon over patient's death. The Journal 7 December 2001: 20

- 13.Norfolk Circuit. Leicester, March 1. The Times 4 February 1867: 11

- 14.Doctor cleared over boy's drug death. The Times 28 April 1978: 4

- 15.Doctor who killed teenager freed. The Times 24 September 2003: 4

- 16.Doctor cleared. The Times 19 May 2004: 416509033

- 17.Before Mr Justice Field. The Times 27 July 1875: 11

- 18.Jury clear surgeon of killing schoolgirl. The Independent 22 December 2001: 8

- 19.Chester, Wednesday, April 10. The Times 12 April 1839: 6

- 20.Midland Circuit, Nottingham, July 21. The Times 23 July 1859: 12

- 21.12 Months for anaesthetist responsible for boy's death, “life in ruins”. The Times 21 February 1959: 4

- 22.Doctor who killed patient on operating table escapes jail. The Independent 24 June 2004: 19

- 23.Central Criminal Court, April 10. The Times 11 April 1862: 10

- 24.R v Webb (1834) 2 Lew CC 196

- 25.R v Crick (1859) 1 F & F 519.

- 26.R v Bateman (1925) 19 Cr App R 8

- 27.R v Adomako [1995] 1 AC 171

- 28.Leahy Taylor J. The Doctor and The Law. London: Pitman Medical & Scientific, 1970

- 29.Loudon ISL. Childbirth. In: Bynum WF, Porter R. Companion Encyclopaedia of the History of Medicine. London: Routledge, 1993: 1050-71

- 30.National Patient Safety Agency, Medical Defence Union, Medical Protection Society. Medical Error. London: National Patient Safety Agency, 2005

- 31.The Crown Prosecution Service. About the CPS. The Principles We Follow. [http://www.cps.gov.uk/about/principles.html] Accessed 26 January 2006