Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory mucocutaneous disease of unknown aetiology with no racial predisposition, although there is a considerable variation in its incidence. Involvement of oesophagus is considered to be extremely rare; the diagnosis is often not made until complications occur. An epidemiological study of 584 patients with oral lichen planus showed oesophageal involvement in only six patients, clearly showing a rare prevalence. The incidence of this disease in dermatology clinics is 1.4%, compared to 3% in oral medicine clinics. We describe a 69-year-old woman who presented with a 2-year history of odynophagia due to oesophageal lichen planus. This case is very unusual in that she had skin involvement 28 years before and had no recurrence.

CASE HISTORY

A 69-year-old retired midwife was referred to the gastroenterology clinic by her general practitioner with a 2-year history of progressive odynophagia. It occurred especially if she ate bulky foods such as bread and potatoes. She was only able to eat extremely slowly and occasionally had choking episodes. Antacids were ineffective, and lansoprazole caused intolerable colic and diarrhoea. Eighteen months previously she had a normal barium swallow and fibreoptic laryngoscopy. She had suffered extensive lichen planus of the skin in 1977 for which she received treatment for 3 months, and had complete remission within a few months. She had no further skin involvement. Subsequently, she had oral lichen planus diagnosed by her dentist 4 years previously, which subsided without treatment. She was not on any regular medications when the referral was made to us. Interestingly, her sister had been diagnosed with lichen planus of the skin a few weeks before. An outpatient gastroscopy was organized.

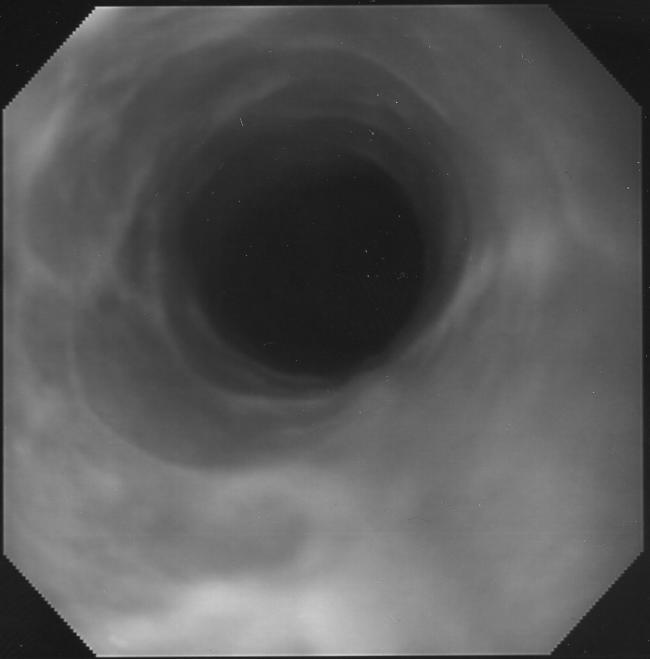

During gastroscopy a lacy network of white lines was visible in the oesophagus representing Wickham's striae of lichen planus (Figure 1). The upper third of oesophagus felt tight and `gripped' the scope. The lower oesophagus looked normal except that she had a small (<5 cm) sliding hiatus hernia. Oesophageal candidiasis was considered as a possibility, but the appearances were not typical of this diagnosis and there were no risk factors for it. Multiple upper oesophageal biopsies were taken, but, to our dismay at this stage, the histopathologist reported that the features were consistent with reflux oesophagitis and that there were no features to suggest lichen planus or candida infection. As per the histopathology report, the patient was put on esomeprazole 40mg once daily. She was followed up 4 weeks later and reported that her symptoms were worse than before. A repeat gastroscopy performed 9 weeks later whilst she was taking esomeprazole revealed the same macroscopic findings as before. Multiple biopsies were again taken from upper oesophagus and the histology showed patchy basal degeneration of squamous epithelium. There was also evidence of dense infiltration of lymphocytes with an occasional Civatte body within squamous epithelium, features consistent with oesophageal lichen planus. Subsequently she has been put on oral prednisolone 40mg per day for 2 weeks, reducing by 5mg per fortnight. She is currently taking 5mg per day and reports 85% improvement in odynophagia.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic view of oesophageal lichen planus

DISCUSSION

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory mucosal disease of unknown aetiology affecting skin, mouth or genitals. Its association with HLA-BW 16, B8, and DR1 suggests the possibility of genetic predisposition.1 It is characterized by shiny, violaceous, flat-topped polygonal papules which retain the skin lines, and which vary in size from pinpoint to a centimetre or more across.2 White lines, known as Wickham's striae may traverse the surface of the papules. Linear lesions often appear along scratch marks or in scars (Koebner phenomenon). Skin lesions may be disfiguring, and involvement of the oral mucosa or genital mucosa in severe cases can be debilitating. While most cases of lichen planus are idiopathic, some may be caused by the ingestion of certain medications (e.g., gold, antimalarial agents, penicillamine, thiazides, beta blockers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, quinidine and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors) or linked to hepatitis C virus infection.3 Diabetes mellitus is a possible associated disease of oral lichen planus4 and candidiasis may also coexist in some patients.

The well-known histopathological features of lichen planus are compact orthokeratosis, wedge shaped hypergranulosis, vacuolar alteration of the basal layer, necrotic keratinocytes (so-called Civatte bodies) and a dense band-like infiltrate composed mostly of lymphocytes.5 Not all of these features must be present to establish the diagnosis of lichen planus.

Oesophageal lichen planus is said to be often unrecognized and underestimated.6 It should always be evaluated for in patients with mucocutaneous involvement. The overwhelming clinical presentation is dysphagia; but reflux-type symptoms, or retrosternal pain, can also be associated. Delay in diagnosis may lead to serial dilations of oesophageal strictures that, without simultaneous medical treatment, may lead to koebenerization of lichen planus and worsening of the stricture. Patients can lose significant weight and become dehydrated secondary to stenosis. Squamous cell cancer developing on mouth lesions is uncommon, but is a potential danger, especially with ulcerated lesions.2 No case has yet been reported in oesophageal lichen planus. After the initial diagnosis of oesophageal lichen planus is made, systemic steroids are often needed to quell the inflammation. A variety of steroid sparing agents have been used successfully, including azathioprine, cyclosporine and etretinate.7 Most patients with symptomatic disease initially respond to immunosuppressant therapy, but recurrent stenosis, in spite of treatment, is common and repeated endoscopic dilatations are necessary in the long run.8

Recognition of oesophageal lichen planus is critical for several reasons. Misinterpretation of the histological features as secondary to reflux disease or as simply a non-specific reaction can lead to delay in the diagnosis and the continuation or worsening of the symptoms.7 It outlines the importance of a proper history and full examination to look for any potential extra oral manifestations of lichen planus. Although no case of carcinoma developing in the setting of oesophageal lichen planus has been reported, some authors think such patients should be followed endoscopically, even prospectively evaluated, for this possibility.9

CONCLUSION

Oesophageal lichen planus is a rare cause of oesophageal symptoms in patients with no active skin or oral lichen planus. A history of lichen planus should be sought in patients presenting with oesophageal symptoms.

References

- 1.Valsecchi R, Bontempelli M, Rossi A, et al. HLA-DR and DQ antigens in lichen planus. Acta Derm Venerol (Stockh) 1988;68: 77-80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breathnach SM, Black MM. Lichen planus and lichenoid reactions. In: Burns T, Breathnach SM, Cox N, Griffiths C, eds. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology, 7th edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2004:42. 6 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katta R. Lichen planus. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61: 3319-24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith MJA. Oral lichen planus and diabetes mellitus. J Oral Med 1977;32: 110-12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acherman AB. Histologic Diagnosis of Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1978

- 6.Eisen D. The evaluation of cutaneous, genital, scalp, nail, oesophageal, and ocular involvement in patients with oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1999;88: 431-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menges M, Hohloch K, Pueschel W, Stallmach A. Lichen planus with oesophageal involvement: a case report and review of the literature. Digestion 2002;65: 184-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham SC, Ravich WJ, Anhalt GJ, Yardley JH, Tsung-Teh W. Oesophageal Lichen planus: case report and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24: 1678-82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickens CM, Heseltine D, Walton S, Bennett JR. The oesophagus in lichen planus: an endoscopic study. BMJ 1990;300: 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]