INTRODUCTION

On 27 January 2006 we celebrated the 250th anniversary of the birth of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, considered by many to be the greatest musical genius that the world has ever known. His life has been chronicled in more detail than any other musician and there are extant about 1200 letters in the Mozart family correspondence that give first-hand information about much of the composer's life. Paradoxically, however, in spite of this wealth of material which is repeatedly being re-assessed, the circumstances of his health and death continue to abound in myth.

The main reason for this anomaly lies in the failure of many authors to take cognizance of the primary sources of information, such as the family letters; instead, they cite the numerous secondary sources, which have accumulated over the years to which are added speculative opinions masquerading as fact. Soon after his death stories began to circulate that he had succumbed to poison administered by his rival Salieri or, according to some, the Freemasons. The poisoning tales have now been laid to rest but many other fables grew up particularly those concerned with his medical history and death some of which show remarkable persistence.

THE LAST PORTRAIT OF MOZART?

Mozart is now so highly regarded that any opportunity is seized upon to associate his name with a newly discovered document, musical manuscript, or portrait in order to enhance its worth; the present anniversary provides another opportunity. There are, in total, 11 authentic portraits of the composer in existence of which there are six depicting him as an adult—one of these was painted several years after his death from a lost original. In addition, there is a very large number, which either cannot be verified or are frankly spurious.1

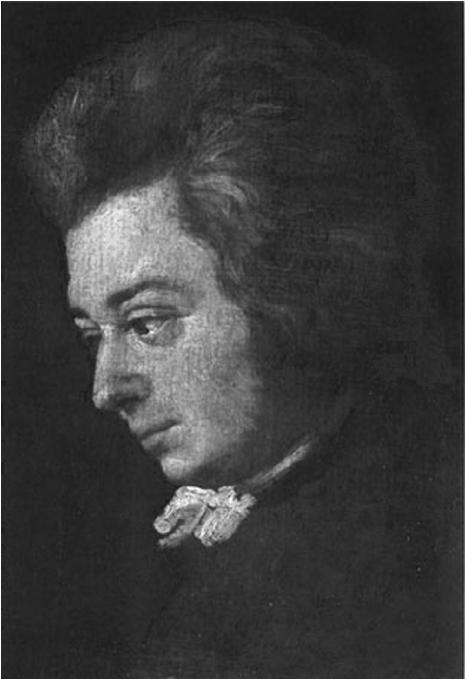

Early in 2005, a picture of an 18th century gentleman which had been languishing in the storage depot of the Berlin Picture Gallery for 70 years was unearthed; it was described as a hitherto unknown portrait of Mozart painted in Munich in the year before his death. (Figure 1). This opinion was based on a computer analysis of the features compared with those of an authentic portrait of Mozart as Knight of the Golden Spur painted 13 years previously, at the age of 21, by an unknown artist and now in the Museum of Music, Bologna. The Berlin portrait is undated and was painted by a German artist, Johann Georg Edlinger. Born in 1741 at Graz, Edlinger went to Munich in 1774. He was appointed by the Elector Karl Theodor as court painter in 1781 at a small salary, but later he seems to have lost favour and in 1819 died impoverished. Today he is regarded as a competent 18th century portraitist and several of his paintings are in the possession of the Munich Neue Pinakothek art gallery where one is currently on view. The Berlin painting shows a man with a greying, puffy appearance, which the curator of the art gallery ascribes to a prematurely aged Mozart, ravaged by treatment for syphilis or by renal failure.2

Figure 1.

Portrait by Johann Georg Edlinger [reproduced by permission of Gemäldegalerie, Statliche Museen zu Berlin, Germany]

There are, however, considerable difficulties about the acceptance of this attribution; there is certainly no evidence for the assertions that he suffered from syphilis or renal failure. The Mozart scholar Volkmar Braunbehrens points out that, while Mozart did stay in Munich in 1790, there is no mention in his letters of any portrait of him being commissioned by the Elector or anyone else during his short visit to the city, nor does the name Edlinger occur anywhere in his correspondence.3 Indeed, Mozart writes that he only intended to stay for 1 day in Munich but was persuaded by the Elector to stay for 6 days to entertain his court guests; during this time he also busied himself by visiting his many friends.4 (p. 947)

The picture chosen for comparison by computer was painted in Salzburg when the composer was 13 years younger; it does not show obvious likenesses with other portraits of his youth—in fact, it is simply that particular artist's interpretation of Mozart's likeness and is not necessarily a valid comparison. Finally, the Berlin painting bears little resemblance to the portrait which Mozart's widow Constanze regarded as the best likeness—that painted in 1789-1790 by his brother-in-law Joseph Lange, now in the Mozarteum, Salzburg (Figure 2). The Lange portrait shows a man whose looks are compatible with the composer's age of about 33 years. The present evidence would seem to be against the attribution of the Berlin picture as Mozart's last portrait. Furthermore, the comments made about Mozart's state of health at the time to account for his appearance in this picture require proper consideration.

Figure 2.

Portrait of Mozart by Joseph Lange [reproduced by permission of Internationale Stiftung Mozarteum]

SYPHILIS

In the 18th century syphilis was widespread and seems to have been even more virulent than today. It was certainly to be found in the musical profession, a notable example being Schubert. That Mozart suffered from the disease was first mentioned in 1804 by J P A Suard in his highly unreliable Anecdotes sur Mozart. He states:

`I have heard it said that he wrote The Magic Flute only to please a woman of the theatre with whom he had fallen in love and who offered him her favours at his price. It is added that his triumph had very cruel consequences and that he contracted from it an incurable disease of which he died shortly after.'5(p. 498)

The treatment of syphilis at this time was by the use of mercury and, among many other causes, it has been blamed for the composer's death. The chronic administration of mercury is associated with a persistent tremor. However, when Mozart's entries in his own catalogue of compositions is examined, his handwriting of only 2 weeks before his fatal illness is shown to be as firm and steady as ever. Therefore, mercury poisoning can be eliminated. In fact, Mozart reacted vehemently whenever he was confronted with evidence of syphilis in any person. In October 1777, when he met his friend the Czech composer Joseph Myslivecek who had contracted the disease and had been admitted to hospital, he reacted with horror to find him hideously disfigured by a nasal gumma which had been cauterized by a surgeon. He says `Nothing can help him. The surgeon, that ass, burnt away his nose. Imagine what he must have suffered'.4 (p. 322) In 1778 he writes about a journey he was making to Strasbourg by carriage and says `One of our fellow travellers was badly affected by the French disease and he didn't deny it either—which in itself was enough to make me prefer to travel by a post-chaise'.4 (p. 622)

In 1781, Mozart sums up his feelings about the disease when writing to his father about the importance to him of getting married. `I have too much horror and disgust—too much dread and fear of diseases, and too much care for my health to fool about with whores'.4 (p. 783)

RENAL DISEASE

There have been many opinions about Mozart's health during his final year and the illness leading to his death, including subacute bacterial endocarditis, acute rheumatic fever and excessive venesections, and even subdural haemorrhage; but the most persistent assertion is chronic renal disease culminating in renal failure. This diagnosis dates back 100 years when Barraud propounded the view that Mozart suffered from nephritis following a supposed attack of scarlet fever at the age of 6—which was, in fact, erythema nodosum according to modern criteria. 6 Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis was considered in more detail by Dr Aloys Greither 50 years later7 and, as we have seen, it is still being perpetuated. The main reason for the diagnosis is that during his last year Mozart is supposed to have become progressively ill with fainting fits, headaches and exhaustion; during his last illness, he was said to be suffering from peripheral oedema but without any mention of dyspnoea. A more recent attempt to demonstrate a cause for renal failure is the assertion that he had repeated attacks of Henoch-Schönlein disease.8

The view that Mozart became severely depressed and suffered progressive ill-health towards the end of his life is fallacious and stems from uncritical acceptance of the stories circulated by the over romantic early biographers. Their information was obtained from one source, Constanze Mozart, and their accounts were written many years after the composer's death. The fact that she initially attempted to pass off The Requiem as completed by her husband demonstrates that her evidence is sometimes questionable. Even if she did not deliberately mislead, she had good opportunities to embellish incidents which had happened in their lives. An example of how the legends arose is to be found in the writing of an early author, Franz Xaver Niemetschek. In the first edition of his biography (1798) he refers to Mozart's health during his stay in Prague in September 1791 when he had just completed his opera La Clemenza di Tito and was greatly overworked—`The composer became sickly and required medication'.9 In the second edition of Niemetschek's work (1808) this has developed into `On bidding farewell to his circle of friends he became so melancholy that he wept. A premonition of his approaching death appeared to have brought on melancholia—for he already bore within him the seed of the illness which soon carried him off'!5 (p. 510)

These stories are in complete contrast to what Mozart himself wrote concerning his life and state of mind at this time.

THE MYTH OF CHRONIC DISEASE

During the last 6 months of Mozart's life he spent much time away from his wife, who was in Baden taking the waters to improve her health. In all, there are in existence 20 letters he wrote to her from Vienna during this period. He repeatedly expresses his great love for her, frets at her absence, and he worries frequently about her health; he makes no mention of any ailments suffered by him. In fact, on 3 July 1791 he wrote very positively `... as for my health I feel pretty well'.4 (p. 959) Only 6 weeks before the onset of his terminal illness he tells his wife `I took my favourite walk by the Glacis to the theatre. But what do I see? What do I smell? Why here is Don Primus with the cutlets. How delicious'.4 (p. 967) The next day he writes `I have just swallowed a delicious slice of sturgeon which Don Primus (who is my faithful valet) brought me and as I have a rather voracious appetite I have sent him off again to fetch some more'.4 (p. 968) In the evening he attended the performance of his opera The Magic Flute. During the performance he was so animated and full of good spirits that he played a practical joke on Schikaneder (in his role of Papageno) by playing the glockenspiel behind the scenes when there should have been silence. The next morning he says he has slept very well and had half a capon for breakfast. In his last letter written 2 days before he went to Baden to fetch Constanze back to Vienna in the middle of October, Mozart recounts that he took their elder son Karl to see The Magic Flute following which he took him back home and they both slept very soundly. He then continues in a very normal state of mind by discussing the plans he had for their son's future education and the requirements for supper that evening.

Mozart's creative output during the last few months of his life was prodigious. He composed the opera La Clemenza di Tito in 18 days for the coronation of Emperor Leopold in Prague in September 1791; during the last 10 weeks he completed The Magic Flute, the clarinet concerto, and composed a cantata for the newly opened premises for his Masonic Lodge, having already begun the Requiem.

Enormous mental energy, an undiminished appetite, normal sleep, and unimpaired fertility (his wife had given birth to their second surviving son on 26 July) are clinical signs of good health and not terminal renal failure or any other serious chronic disease. There is, therefore, no reason whatever to suggest that the Berlin picture is a portrait of Mozart showing signs of severe ill health.

THE LAST ILLNESS AND DEATH

In spite of a very large literature devoted to Mozart's death most of it is purely speculative and the cause remains uncertain. Unfortunately, his medical attendants Dr Closset and Dr Salaba have left no clinical account of his condition. Their diagnosis was heated miliary fever, which simply means a fever with a rash. The information upon which so much speculative writing has subsequently been based derives from the descriptions given by Mozart's sister-in-law, and to a lesser extent his widow, many years later for the biography of the composer by Constanze's second husband, some of which is contradictory. The fact, however, that he enjoyed normal health during his last year means that his death was due to an acute illness which struck him down only 2 days after he had conducted the recently composed Masonic Cantata. This receives confirmation from the testimony of the well-respected Dr Edward Guldener von Lobes, medical superintendent of Lower Austria, who had been in consultation with Dr Closset over the case. He refers to an epidemic which raged in Vienna in the late autumn of 1791 and said `... this malady attacked at this time a great many of the inhabitants and not for a few of them it had the same fatal conclusions and the same symptoms as in the case of Mozart'.5 (p. 523) Over the distance of two centuries the nature of this epidemic remains speculative; one suggestion is scarlet fever with the complication of streptococcal septicaemia. At that time, infections of various kinds were the most common cause of death; the standard treatment for fevers was venesection, emetics and purgatives all of which would have contributed to a fatal outcome. It should be remembered that several of Mozart's contemporaries died prematurely. Two of his own physicians died aged 29 and 33. His great friend, Count von Hatzfield, a violinist, died of a sudden pulmonary infection following which, on 4 April 1787, Mozart wrote sadly `He was just thirty one, my own age'.4 (p. 908) In this respect Mozart's death was no different from many others in 18th century Vienna.

CONCLUSION

Contrary to widespread opinion Mozart did not suffer from chronic ill health during the last part of his life and death came as a result of an acute infectious illness.

A picture of an 18th century gentleman recently described as the last portrait of Mozart ravaged by syphilis or renal disease is most unlikely to be authentic since he was in good health at the time the picture is said to have been painted and it bears little resemblance to the portrait endorsed by his wife Constanze.

References

- 1.Zenger M, Deutsch O E. Mozart und seine Welt in zeitgenössischen Bildern. Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1961

- 2.Sunday Telegraph 9 January 2005

- 3.Braunbehrens V. Die Presse, Vienna13 January 2005

- 4.Anderson E, ed. The Letters of Mozart and His Family, 3rd edn. London: Macmillan, 1985

- 5.Deutsch OE. Mozart: A Documentary Biography. London: Adam & Charles Black, 1966

- 6.Barraud J. A quelle maladie a succombé Mozart. Chronique méd 1905; 22: 737-4412955675 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greither A. Mozart und dieÄrzte, seine Krankenheiten und sein Tod. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1956; 81: 165-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies P J. Mozart's last months and controversial death. J Med Biog 1994; 2: 44-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niemetschek F X. Leben des k.k. Kapellmeisters Wolfgang Gottlieb Mozart, translated by H Mautner, Prague 1798. London: Leonard Hyman, 1956: 43