Legal chewing of khat leaves is prevalent in East African migrants to the UK; however severe cardiac ischaemia and liver damage can result.

Khat also known as qat or chat is the fresh leaves of Catha edulis. It is a shrub grown in East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula where khat chewing is common with open legal trade. Around 20 million people use khat in these countries and its use has spread to the immigrant communities across Europe and America. The 2001 census records 44 000 Somalis in the UK and estimates of 95 000 were made in 2003. On chewing, khat leaves release amphetamine-like constituents; cathinone and cathin and other alkaloids (cathulidins). Khat is currently legal in the UK though cathinone and cathin are controlled drugs (Misuse of Drugs Act 1971). Khat is illegal in the USA, Canada, Norway and Sweden.

CASE HISTORY

A 33-year-old East African man presented with acute onset chest pain. He smoked (15 pack years), but had no other coronary risk factors (cholesterol 4.8 mmol/L). The patient had been chewing khat almost constantly for 2-3 days, but denied a regular habit; no reason for this change in behaviour was given. He took no medication and did not use illegal drugs.

His electrocardiogram (ECG) showed acute anterior myocardial infarction. After thrombolysis with rt-PA his pain resolved but the ECG showed no signs of reperfusion. Calcium channel antagonists were given intravenously for possible vasospasm. Troponin T at 12 h was 10.11 μg/L (normal range <0.01) indicating myocardial infarction. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed anteroseptal and apical akinesis with a moderately impaired left ventricle. The patient refused coronary angiography and received medical therapy of aspirin, an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, a β-blocker and a statin.

The patient failed to attend for follow up having stated that he relied on his faith for his health. He returned 27 months later with shortness of breath at rest and intermittent chest pain. In the interim, he had continued daily khat chewing. He was short of breath at rest, tachycardic, normotensive, and had a pansystolic murmur. He had signs of biventricular failure. Electrocardiogram showed his previous myocardial infarction without acute changes. Troponin T was 0.09 μg/L. Echocardiography revealed severely impaired biventricular function (ejection fraction of 15%, normal range 65-80%).

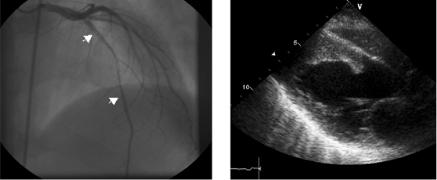

Coronary angiography showed a 6 cm stenosis in the left anterior descending coronary artery and filling defects consistent with thrombus. The other coronary arteries were normal (Figure 1a). A dobutamine stress echocardiogram revealed no symptoms or electrocardiogram changes at peak stress and failed to show significant contractile reserve or viability suggesting an established infarct with no salvageable myocardium. In view of the negative stress echocardiogram, coronary intervention was not attempted and the patient was discharged on perindopril, carvedilol, frusemide, clopidogrel, simvastatin and spironolactone.

Figure 1.

(a) Coronary angiogram showing 6 cm stenosis in the left anterior descending artery (arrows) filled with clot. (b) Transthoracic echocardiogram (parasternal long axis view) showing a large apical left ventricle clot (arrows)

One month later, he returned with worsening chest pain and shortness of breath having stopped taking all his medications. He was hypotensive (104/64 mmHg), his jugular venous pulse was elevated and his electrocardiogram was unchanged despite a Troponin T of 1.83 μg/L. The patient had impaired liver function from admission, which continued to deteriorate with peak alanine transaminase of 626 IU/L. Ultrasound showed an enlarged liver with reduced echogenicity consistent with acute hepatitis. A hepatitis screen was negative (B and C, autoantibodies) as was an HIV test. The patient's left ventricle had deteriorated and echocardiography showed an extensive mural thrombus in the apex of his severely impaired left ventricle (Figure 1b). He was anticoagulated with warfarin and intravenous diuretics were required to treat fluid overload. An implantable cardioverter defibrillator was not attempted at this admission due to the risk of embolism from the left ventricle thrombus. Ultimately, the patient was discharged on maximal medical therapy after a 6-week stay to stabilize his severe biventricular failure.

COMMENT

Khat contains alkaloids cathulidins and cathinone which mediate its sympathomimetic effects.1 These release serotonin and dopamine in the central nervous system and noradrenaline from peripheral sympathetic neurones.1 Cathinone has a similar action to amphetamine and cocaine causing an elevation in blood pressure and heart rate proportional to blood levels which peak 1.5-3.5 h after chewing.2 Myocardial oxygen demand increases followed by catecholamine-mediated platelet aggregation and coronary vasospasm.3 We describe a case of severe ischaemic cardiomyopathy due to khat-related myocardial infarction.

A case-control study in the Yemen comparing 100 patients with acute myocardial infarction to 100 age- and sex-matched controls showed a 39-fold increased myocardial infarction risk in heavy khat chewers. In a multivariate analysis the relative risk of myocardial infarction associated with khat was 5.0 (confidence interval 1.9-13.1).4 Our patient's unusually sustained khat use for 2-3 days without sleep probably caused his extensive infarction.

No published guidelines exist for the optimal management of khat-induced coronary ischaemia; however, extrapolation from cocaine-associated myocardial infarction supports use of benzodiazepines, calcium channel blockers and nitrates with coronary intervention if these are unsuccessful.5

To date, khat-associated human hepatotoxicty is unknown; but rabbit studies implicate long-term high dose khat use in chronic hepatic inflammation and porto-portal fibrosis with associated liver dysfunction.6 Our patient's hepatitis was is probably due to right heart failure and possible direct khat toxicity (it did not respond to withdrawal of statin or proton pump inhibitor).

Khat also causes gingivitis and tooth loss and may increase oesophageal cancer risk.7 Case reports implicate khat usage in memory impairment, depression and psychoses.7 The World Health Organization classifies khat as causing psychological, but not physical dependence.7

The practice of chewing khat leaves has been a part of the culture in areas of East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula since the 7th century. In these regions, khat is traded openly and is used socially across a range of age and class groups, particularly as alcohol is not permitted in Islam. It also has religious association and has been described as an aid to religious devotion and prayer. Migrants from these regions see khat chewing as integral to retaining their cultural and social identity. However, approval is not universal and varies with gender, region and generation; there is an awareness of the harmful effects on health and productivity.8 This differing of opinion was reflected in a survey by Nacro, a government drugs charity. This showed that in the UK, although 50% of Somali men regularly use khat and 35% of the 553 Somalis interviewed regarded it as important to cultural identity, 49% wanted to see it criminalized.9 The legal status of khat is currently under Home Office review. Although the harmful effects of chronic khat usage have been widely reported, the cultural effects of a ban on an immigrant minority need to be considered.

Our patient demonstrates its adverse effects on multiple organ systems including, not only the severe cardiovascular consequences of long-term khat use, but also its possible hepatotoxicity. Increased medical awareness of khat's availability and use by urban migrant populations in the UK is needed to allow prompt treatment of coronary ischaemia, particularly in young male khat chewers with few other risk factors for coronary disease.

Acknowledgments We would like to acknowledge Dr Malcolm Walker's contribution to this patient's care and preparation of this report.

Competing interests None.

References

- 1.Kalix P. A comparison of the catecholamine releasing effect of the khat alkaloids (-)-cathinone and (+)-norpseudoephidrine. Drug Alcohol Depend 1983;11: 395-401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halket JM, Karasu Z, Murray-Lyon IM. Plasma cathinone levels following chewing khat leaves. J Ethnoparmacol 1995;49: 111-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Motarreb AL, Broadly KJ. Coronary and aortic vasoconstriction by cathinone, the active constituent of khat. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol 2003; 23: 319-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Motarreb AL, Briancon S, Al-Jaber N, et al. Khat chewing is a risk factor for acute myocardial infarction: a case control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005;59: 574-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braunwald E, Antman E, Beasley J, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40: 1366-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Habori M, Al-Aghbari A, Al-Mamary M, et al. Toxicological evaluation of Catha edulis leaves: a long term feeding experiment in animals. J Ethnopharmacol 2002;83: 209-17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houghton P. Khat—a growing concern in the UK. Pharmaceutical J 2004;272: 163-5 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevenson M, Fitzgerald J, Banwell C. Chewing as a social act: cultural displacement and khat consumption in the East African communities of Melbourne. Drug Alcohol Rev 1996;15: 73-82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel SL, Murray R. Khat chewing amongst Somalis in four English cities. [http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs05/r266.pdf]