Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To summarize clinical recognition and current management strategies for four types of acneiform facial eruptions common in young women: acne vulgaris, rosacea, folliculitis, and perioral dermatitis.

QUALITY OF EVIDENCE

Many randomized controlled trials (level I evidence) have studied treatments for acne vulgaris over the years. Treatment recommendations for rosacea, folliculitis, and perioral dermatitis are based predominantly on comparison and open-label studies (level II evidence) as well as expert opinion and consensus statements (level III evidence).

MAIN MESSAGE

Young women with acneiform facial eruptions often present in primary care. Differentiating between morphologically similar conditions is often difficult. Accurate diagnosis is important because treatment approaches are different for each disease.

CONCLUSION

Careful visual assessment with an appreciation for subtle morphologic differences and associated clinical factors will help with diagnosis of these common acneiform facial eruptions and lead to appropriate management.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Faire le point sur le diagnostic clinique et les modalités thérapeutiques actuelles de quatre types d’éruptions faciales acnéiformes chez la femme jeune: l’acné vulgaire, l’acné rosacée, la folliculite et la dermatite périorale.

QUALITÉ DES PREUVES

Le traitement de l’acné vulgaire a fait l’objet de plusieurs essais randomisés ces dernières années. Les recommandations pour le traitement de l’acné rosacée, de la folliculite et de la dermatite périorale reposent surtout sur des essais comparatifs ou ouverts (preuves de niveau II), mais aussi sur des opinions d’experts et des déclarations de consensus (preuves de niveau III).

PRINCIPAL MESSAGE

Les femmes jeunes consultent fréquemment les établissements de soins primaires pour des éruptions faciales acnéiformes. Il est souvent difficile de distinguer des conditions morphologiquement semblables. Il importe toutefois de poser un diagnostic précis car les modalités thérapeutiques diffèrent d’une maladie à l’autre.

CONCLUSION

Le diagnostic et le traitement des éruptions faciales communes sont plus faciles si l’on fait une évaluation visuelle attentive et si on tient compte des différences morphologiques subtiles et des facteurs cliniques associés.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

Acneiform facial eruptions, including acne vulgaris, rosacea, folliculitis, and perioral dermatitis, are common in young women and cause much medical and psychological distress.

Treatment for acne vulgaris varies with severity, beginning with antimicrobials (benzoyl peroxide), comedolytics (tretinoin), and topical or oral antibiotics (tetracycline, clindamycin, erythromycin). Resistant cases or nodular or scarring acne should be referred to dermatologists for isotretinoin or steroid injection.

Rosacea affects primarily women in their 20s and 30s and requires long-term management including avoiding triggers and using topical metronidazole or oral tetracycline-minocycline. Topical retinoids or isotretinoin are used for severe cases.

Perioral dermatitis has a classic presentation but unknown etiology. Removing fluorinated topical steroids and taking oral tetracycline are effective measures.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Les éruptions acnéiformes du visage comme l’acné vulgaire, l’acné rosacée, la folliculite et la dermatite périorale sont fréquentes chez la femme jeune et sont une source de préoccupation médicale et psychologique.

Le traitement de l’acné vulgaire est fonction de sa sévérité; on utilise d’abord les antimicrobiens (peroxyde de benzoyle), les comédolytiques (trétinoïne) et les antibiotiques topiques ou oraux (tétracycline, clindamycine, érythromycine). Les cas résistants de même que l’acné nodulaire ou cicatrisant devraient être dirigés en dermatologie pour un traitement par l’isotrétinoïne ou par injections de stéroïdes.

L’acné rosacée affecte principalement les femmes de 20 à 40 ans et elle exige un traitement prolongé qui comprend l’évitement des facteurs déclencheurs et l’usage de métronidazole topique et de tétracycline-minocycline orale. Les rétinoïdes et l’isotrétinoïne topiques sont réservés aux cas sévères.

La dermatite périorale a une présentation classique, mais son étiologie est obscure. Elle répond bien à l’arrêt des stéroïdes fluorinés topiques et à la tétracycline orale.

Acneiform eruptions, such as acne vulgaris, rosacea, folliculitis, and perioral dermatitis, are routinely encountered in primary care. Acne vulgaris alone affects up to 80% of adolescents and continues to affect 40% to 50% of adult women.1 An estimated 13 million Americans are affected by rosacea.2 These conditions often have psychosocial sequelae.3

These four eruptions are challenging to diagnose because they all resemble acne. This article describes these eruptions, highlighting the salient distinguishing characteristics, and summarizes current management recommendations from the medical literature.

Quality of evidence

PubMed was searched from January 1966 to December 2003 using the names of each of the acneiform conditions combined with “treatment.” Several randomized controlled trials (level I evidence) on treatment of acne vulgaris were found, but there was little level I evidence for treating the other conditions. Recommendations for treating these conditions are based mainly on comparison or open-label studies (level II evidence) and expert opinion and consensus guidelines (level III evidence).

Acne vulgaris

Acne vulgaris is a disease of the sebaceous follicles that primarily affects adolescents but not uncommonly persists through the third decade and beyond, particularly in women. Pathogenesis is multifactorial and involves an interplay between abnormal follicular keratinization or desquamation, excessive sebum production, proliferation of follicular Propionibacterium acnes, and hormonal factors.

Diagnosis is often clear, and laboratory investigations are unnecessary, except where signs and symptoms suggest hyperandrogenism.4,5 Acne is characterized by a variety of lesions that indicate varying degrees of disease severity.

Mild or noninflammatory acne is characterized by comedones. Closed comedones appear as pale white, slightly elevated, dome-shaped, 1- to 2-mm papules with no clinically visible follicular orifice (Figure 1). Open comedones are flat or slightly raised lesions with a visible central orifice filled with a brown-black substance (Figure 1). Inflammatory acne has a range of lesions. Papules (Figure 1) are often encircled by an inflammatory halo, and pustules can be identified by a central core of purulent material. Nodules are rounder and deeper to palpation than papules and are often tender. Cysts have a propensity to scar and essentially feel like fluctuant nodules. Acne scars (Figure 1) usually appear as sharply punched out pits.

Figure 1. Acne vulgaris in various stages.

A) Several closed comedones (1-mm to 2-mm pale white, dome-shaped papules); B) Several open comedones, papules with a central orifice filled with a brown-black substance; C) Acne papule; D) Several punched-out depressions marking acne scars.

Before commencing therapy and in the interest of establishing a therapeutic alliance, it is important to explain to patients the causes of acne and the rationale for therapy as well as the expected duration of therapy (weeks to months). The literature suggests that therapy be based on the severity or the predominant morphologic variant of disease.

Mild comedonal acne should be treated with topical antimicrobials,1,6-8 such as benzoyl peroxide (available in 2.5/5/10% cream, gel, or wash) or topical comedolytics,1,6-8 such as tretinoin (available in 0.025/0.05/0.1% cream, 0.01/0.025% gel, and 0.05% liquid) (Table 19-24). Benzoyl peroxide is preferred for patients with inflammation8; tretinoin is effective for cases with a predominance of comedones. The recently developed topical retinoid, adapalene, is only marginally more effective than tretinoin, but is better tolerated.7 Choice of treatment depends largely on patients’ tolerance and preference.6 Gels and creams with water bases are less drying than gels in alcohol or glycol bases. Exfoliants, such as salicylic acid, remain an option for acne treatment, but are ineffective for deep comedones and can be irritating.1

Table 1.

Recommendations for treating acne vulgaris

Roman numerals indicate level of evidence.

Papular and pustular acne can be treated with topical or oral antibiotics (Table 19-24). Both topical erythromycin (available as solution, gel, or pledgets) and clindamycin (available as solution, gel, lotion, or pledgets) are reported to be equally effective.9,25 Topical erythromycin is considered safest during pregnancy.1

Combination topical products, such as Clindoxyl (clindamycin and benzoyl peroxide) and Benzamycin (benzoyl peroxide and erythromycin), have recently come on the market and are quite useful.6 Tetracycline (1000 mg/d in two or four divided doses), because of its effectiveness and low cost, is the first-choice oral antibiotic followed by minocycline (50 to 100 mg/d) or doxycycline (100 mg/d). These drugs are often prescribed, along with topical retinoids, combination products, or antimicrobials, to improve efficacy and prevent resistance from developing. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is best reserved for severe, recalcitrant cases.1 Other oral antibiotics mentioned in the literature include erythromycin, clindamycin, ampicillin, and amoxicillin in no particular order. Most of these drugs should be used for at least 2 months before they are deemed ineffective.6

Cases of treatment-resistant, nodulocystic, or scarring acne should be referred to a dermatologist for isotretinoin treatment, steroid injection, or hormone therapy (Table 19-24). Isotretinoin is notorious for its drying side effects and teratogenicity, but is a very effective medication with a response rate as high as 90%.1 It is administered at 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg daily and titrated to obtain an optimal and early response with minimal side effects. Average duration of therapy is 4 months; a second course might be necessary. Triamcinolone acetonide intralesional injections are feasible for sparser nodulocystic lesions, but care must be taken to avoid steroid atrophy. Finally, for women unresponsive to conventional therapy, hormonal therapy (biphasic or triphasic contraceptive pills or spironolactone, which has strong antiandrogenic activity) is recommended in conjunction with topical treatment.1,8

Rosacea

Rosacea is a chronic vascular acneiform facial disorder that affects primarily 20- to 60-year-old people of northern and eastern European descent. Although the condition is equally prevalent in men and women, it is usually more severe in men and can progress to tissue hyperplasia. Pathogenesis remains unknown, although many factors including bacteria, Demodex mites, vasomotor and connective tissue dysfunction, and topical corticosteroids have been implicated.

Rosacea is characterized by a triad of symmetrical erythema, papules and pustules, and telangiectasia on the cheeks, forehead, and nose (Figures 2 and 3). The absence of comedones is an important factor that differentiates rosacea from acne vulgaris. Rosacea follows a course of exacerbations and remissions and is often aggravated by sun, wind, and hot drinks. Frequent flushing, mild telangiectasia, increased telangiectasia with acneiform eruptions, and tissue hyperplasia are the four sequential stages of the condition. Rosacea can also be associated with ocular symptoms of burning, redness, itching, sensation of a foreign body, tearing, dryness, photophobia, and eyelid fullness or swelling.26

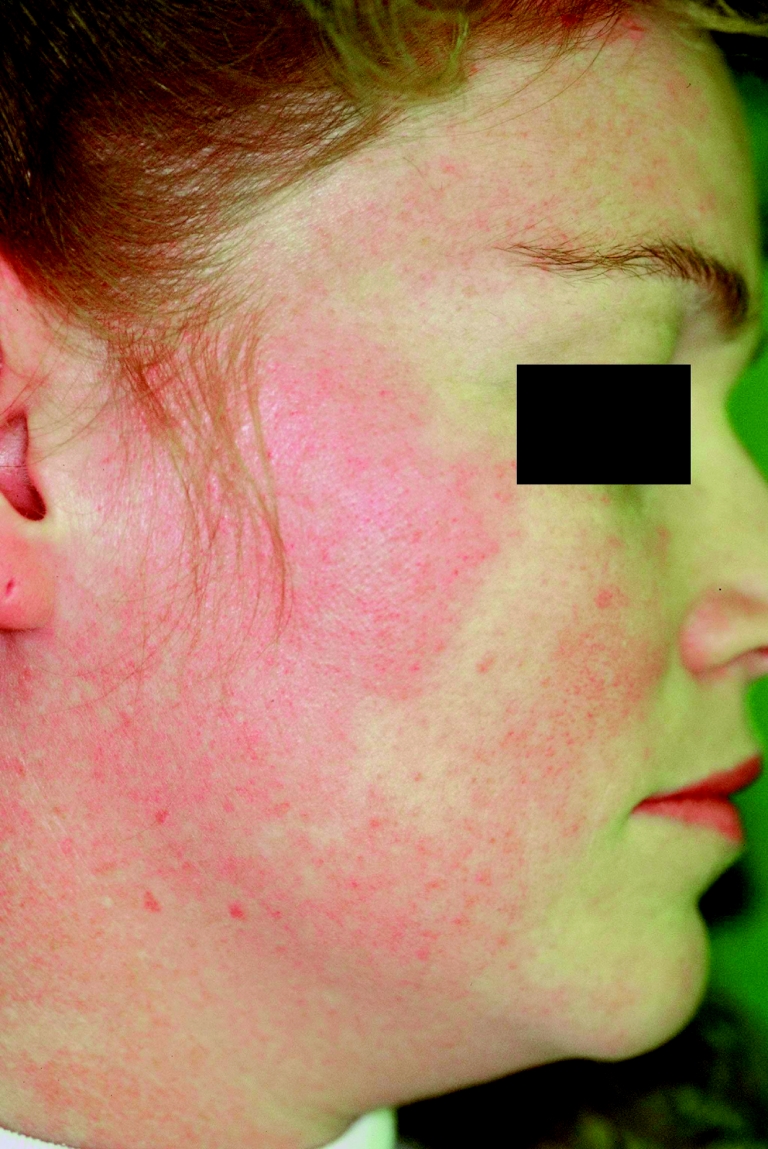

Figure 2. Rosacea.

A young woman has persistent erythema and red papules on both cheeks. No comedones are visible.

Figure 3. Rosacea.

Rosacea can persist into later decades. This older woman has deep symmetrical erythema and many red papules on her cheeks, forehead, and chin.

Begin treatment by discussing potential triggers and how to avoid them. Concomitant topical metronidazole and oral tetracycline are recommended as first-line therapy for early-stage rosacea27,28 (Table 229-33). This combination lowers the potential for relapse once the oral medication is withdrawn.27,28 Oral minocycline (100 to 200 mg/d) is considered an acceptable alternative.28 Doxycycline, clindamycin, erythromycin, clarithromycin, ampicillin, and metronidazole have also been shown to be effective (Table 229-33). Oral therapy should be prolonged in those with ocular symptoms, although some sources recommend deferring oral antibiotics until there are ocular complaints.34

Table 2.

Recommendations for treating rosacea

Roman numerals indicate level of evidence.

There is no significant difference in efficacy between twice-daily treatment with 0.75% topical metronidazole and once-daily treatment with 1.0% metronidazole.27 Topical sulfacetamide is an alternative if metronidazole is not tolerated or if patients want concealment (sulfacetamide is available in a flesh-coloured preparation) (Table 229-33). Oral tetracycline is usually started at 1000 mg/d, tapered, and finally discontinued. Various sources recommend various tapering protocols and duration of therapy. Some recommend tapering to 500 mg/d over 6 weeks followed by a slow maintenance taper to 250 mg/d over 3 months if patients respond; otherwise, a 6-week course of full-dose tetracycline should be repeated.2 Others recommend therapy at full dose until clearance or for 12 weeks’ duration.28 Recently, topical retinoid and vitamin C preparations have been shown to have a beneficial effect29,32 (Table 229-33).

For recalcitrant rosacea, a 4- to 5-month course of oral isotretinoin at either low dose (10 mg/d) or the dose used for acne vulgaris has been shown to reduce symptoms.35 Patients with rosacea with fibrotic changes should be referred to a cosmetic surgeon.

Folliculitis

Folliculitis is an inflammation of the hair follicle as a result of mechanical trauma (eg, shaving, friction), irritation (certain topical agents, such as oils), or infection. Mechanical trauma, occlusion, and immunocompromise predispose patients to infection. The usual infectious organism is Staphylococcus aureus, although Gram-negative folliculitis can result from prolonged use of antibiotics for acne. Pityrosporum, a saprophytic yeast, has also been implicated.

Diagnosis is clinical. There is usually an abrupt eruption of small, well circumscribed, globular, dome-shaped, often monomorphic pustules in clusters on hair-bearing areas of the body and face (Figure 4). Deeper follicular infections, or sycosis, although rare, are more erythematous and painful.

Figure 4. Folliculitis.

A cluster of small monomorphic pustules appears on a woman’s forehead.

Initially, potassium hydroxide testing of the hair and any surrounding scale should be considered to exclude Pityrosporum. Otherwise, an identifying culture should always be taken before initiating therapy.34 In confirmed cases, topical therapy with econazole cream, selenium sulfide shampoo, or 50% propylene glycol36 has been recommended for a duration of 3 to 4 weeks (Table 337-41). Subsequent additional intermittent maintenance doses once to twice a week42 have been found helpful for avoiding recurrence, which is common in folliculitis. Oral antifungals (fluconazole, ketoconazole, or itraconanzole) have been deemed effective when used for 10 to 14 days43 (Table 337-41). One clinical trial demonstrated the superiority of combined topical and oral therapy as compared with either alone.37

Table 3.

Recommendations for treating folliculitis

Roman numerals indicate level of evidence.

Topical therapy for superficial S aureus includes erythromycin, clindamycin, mupirocin, or benzoyl peroxide44 (Table 337-41). Oral antistaphylococcal antibiotics (first-generation cephalosporins, penicillinase-resistant penicillins, macrolides, or fluoroquinolones) are indicated for extensive disease or for the deep involvement of sycosis44 (Table 337-41). Treatment is continued until lesions completely resolve.45 Gram-negative folliculitis can be treated as severe acne with isotretinoin at a dose of 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg daily for 4 to 5 months46 (Table 337-41). Alternatives are ampicillin at 250 mg or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole at 600 mg four times daily, but response to antibiotic treatment is slow, and relapse is common.

Perioral dermatitis

Perioral dermatitis is an acneiform eruption of unknown etiology, although many contributing factors have been implicated: fluorinated topical corticosteroids, subclinical irritant contact dermatitis, and overmoisturization of skin. Women are affected more than men.47

Clinically, the condition appears as an eruption of discrete, symmetrical pinpoint papules and pustules in clusters periorally (on the chin or nasolabial folds, but not on the vermilion border of the lips) that might have an erythematous base (Figure 5). Similar and concomitant lesions are sometimes found at the lateral borders of the eyes.

Figure 5. Perioral dermatitis.

Pinpoint erythematous papules, some confluent, are distributed in a perioral array distinctly sparing the vermilion border of the lip.

Despite an unclear etiology, treatment is simple and effective. Perioral dematitis resolves with tetracycline (250 mg two to three times daily for several weeks)48 or erythromycin49 (Table 450,51). Topical antibiotics are less well tolerated and less effective, but remain an option for those who cannot take systemic antibiotics.27 Topical fluorinated corticosteroids should be discontinued. Gradually weaker topical corticosteroids for weaning and prevention of rebound eruptions have been used either as monotherapy or as additional agents to topical metronidazole and oral erythromycin.52

Table 4.

Recommendations for treating perioral dermatitis

Roman numerals indicate level of evidence.

Conclusion

Acneiform facial eruptions are common in young women. Differential diagnosis of the four conditions discussed above should be kept in mind when assessing patients. Although there is some overlap in how these conditions present, careful attention to distribution of lesions, morphology, and exacerbating factors can lead to accurate diagnosis and optimal therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Thomas G. Salopek and Dr Benjamin Barankin for supplying some figures for this article.

Biography

Dr Cheung is a dermatology resident, Dr Taher has completed dermatology residency, and Dr Lauzon is an Associate Professor and Director in the Division of Dermatology, all at the University of Alberta in Edmonton.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Nguyen QH, Kim YA, Schwartz RA. Management of acne vulgaris. Am Fam Physician. 1994;50(1):89–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuevas T. Identifying and treating rosacea. Nurse Pract. 2001;26(6):13. doi: 10.1097/00006205-200106000-00003. 13-5,19-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta MA. Psychosocial aspects of common skin diseases. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:660. 660-5 (Eng), 668-70 (Fr) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jabbour SA. Cutaneous manifestations of endocrine disorders: a guide for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4(5):315–331. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tourniaire J, Pugeat M. Strategic approach of hyperandrogenism in women. Horm Res. 1983;18(1-3):125–134. doi: 10.1159/000179785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor MB. Treatment of acne vulgaris: guidelines for primary care physicians. Postgrad Med. 1991;89(8):40–47. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1991.11700952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunliffe WJ. Management of adult acne and acne variants. J Cutan Med Surg. 1998;2(Suppl 3):7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burdon-Jones D. New approaches to acne. Aust Fam Physician. 1992;21(11):1615–1622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shalita AR, Smith EB, Bauer E. Topical erythromycin versus clindamycin therapy for acne. A multicenter, double-blind comparison. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:351–355. doi: 10.1001/archderm.120.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes BR, Norris JF, Cunliffe WJ. A double-blind evaluation of topical isotretinoin 0.05%, benzoyl peroxide gel 5% and placebo in patients with acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17(3):165–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1992.tb00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nyirady J, Grossman RM, Nighland M, Berger RS, Jorizzo JL, Kim YH, et al. A comparative trial of two retinoids commonly used in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Dermatol Treat. 2001;12(3):149–157. doi: 10.1080/09546630152607880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pochi PE, Bagatell FK, Ellis CN, Stoughton RB, Whitmore CG, Saatjian GD, et al. Erythromycin 2 percent gel in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 1988;41(2):132–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuhlman DS, Callen JP. A comparison of clindamycin phosphate 1 percent topical lotion and placebo in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 1986;38(3):203–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lookingbill DP, Chalker DK, Lindholm JS, Katz HI, Kempers SE, Huerter CJ, et al. Treatment of acne with a combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide gel compared with clindamycin gel, benzoyl peroxide gel and vehicle gel: combined results of two double-blind investigations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37(4):590–595. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chalker DK, Shalita A, Smith JG, Jr, Swann RW. A double-blind study of the effectiveness of a 3% erythromycin and 5% benzoyl peroxide combination in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9(6):933–936. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gammon WR, Meyer C, Lantis S, Shenefelt P, Reizner G, Cripps DJ. Comparative efficacy of oral erythromycin versus oral tetracycline in the treatment of acne vulgaris. A double-blind study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 Pt 1):183–186. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cullen SI, Cohan RH. Minocycline therapy in acne vulgaris. Cutis. 1976;17(6):1208. 1208-10,1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parsad D, Pandhi R, Nagpal R, Negi KS. Azithromycin monthly pulse vs daily doxycycline in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Dermatol. 2001;28(1):1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2001.tb00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panzer JD, Poche W, Meek TJ, Derbes VJ, Atkinson W. Acne treatment: a comparative efficacy trial of clindamycin and tetracycline. Cutis. 1977;19(1):109–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunliffe WJ, Meynadier J, Alirezai M, George SA, Coutts I, Roseeuw DI, et al. Is combined oral and topical therapy better than oral therapy alone in patients with moderate to moderately severe acne vulgaris? A comparison of the efficacy and safety of lymecycline plus adapalene gel 0. 1%, versus lymecycline plus gel vehicle. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(3 Suppl):218–226. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)01153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine RM, Rasmussen JE. Intralesional corticosteroids in the treatment of nodulocystic acne. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:480–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peck GL, Olsen TG, Butkus D, Pandya M, Arnaud-Battandier J, Gross EG, et al. Isotretinoin versus placebo in the treatment of cystic acne. A randomized double-blind study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6(4 Pt 2 Suppl):735–745. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)70063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosen MP, Breitkopf DM, Nagamani M. A randomized controlled trial of second- versus third-generation oral contraceptives in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(5):1158–1160. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatwal A, Bhatt RP, Agrawal JK, Singh G, Bajpai HS. Spironolactone and cimetidine in treatment of acne. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh) 1988;8(1):84–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schachner L, Pestana A, Kittles C. A clinical trial comparing the safety and efficacy of a topical erythromycin-zinc formulation with a topical clindamycin formulation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22(3):489–495. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70069-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zug KA, Palay DA, Rock B. Dermatologic diagnosis and treatment of itchy red eyelids. Surv Ophthalmol. 1996;40(4):293–306. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(96)82004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuber TJ. Rosacea. Dermatology. 2000;27(2):309–318. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen AF, Tiemstra JD. Diagnosis and treatment of rosacea. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(3):214–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlin RB, Carlin CS. Topical vitamin C preparation reduces erythema of rosacea. Cosmetic Dermatol. 2001;2:35–38. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dahl MV, Katz HI, Krueger GG, Millikan LE, Odom RB, Parker F, et al. Topical metronidazole maintains remissions of rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:679–683. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkin JK, DeWitt S. Treatment of rosacea: topical clindamycin versus oral tetracycline. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32(1):65–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vienne MP, Ochando N, Borrel MT, Gall Y, Lauze C, Dupuy P. Retinaldehyde alleviates rosacea. Dermatology. 1999;199(Suppl 1):53–56. doi: 10.1159/000051380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoting E, Paul E, Plewig G. Treatment of rosacea with isotretinoin. Int J Dermatol. 1986;25(10):660–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1986.tb04533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mengesha YM, Bennett ML. Pustular skin disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3(6):389–400. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200203060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erdogan FG, Yurtsever P, Aksoy D, Eskioglu F. Efficacy of low-dose isotretinoin in patients with treatment-resistant rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:884–885. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.7.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Back O, Faergemann J, Hornqvist R. Pityrosporum folliculitis: a common disease of the young and middle-aged. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(1 Pt 1):56–61. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abdel-Razek M, Fadaly G, Abdel-Raheim M, al-Morsy F. Pityrosporum (Malassezia) folliculitis in Saudi Arabia—diagnosis and therapeutic trials. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20(5):406–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1995.tb01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parsad D, Saini R, Negi KS. Short-term treatment of pityrosporum folliculitis: a double blind placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;11(2):188–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.1998.tb00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bork K, Brauers J, Kresken M. Efficacy and safety of 2% mupirocin ointment in the treatment of primary and secondary skin infections—an open multicentre trial. Br J Clin Pract. 1989;43(8):284–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tassler H. Comparative efficacy and safety of oral fleroxacin and amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium in skin and soft tissue infections. Am J Med. 1993;94(3A):159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plewig G, Nikolowski J, Wolff HH. Action of isotretinoin in acne rosacea and Gram-negative folliculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6(4 Pt 2 Suppl):766–785. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)70067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faergemann J. Pityrosporum infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(3 Pt 2):18–20. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81261-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aly R, Berger T. Common superficial fungal infections in patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22(Suppl 2):128–132. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.supplement_2.s128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stulberg DL, Penrod MA, Blatny RA. Common bacterial skin infections. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(1):119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berger TG. Treatment of bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections in the HIV-infected host. Semin Dermatol. 1993;12(4):296–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boni R, Nehroff B. Treatment of Gram-negative folliculitis in patients with acne. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4(4):273–276. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hogan DJ. Perioral dermatitis. Curr Prob Dermatol. 1995;22:98–104. doi: 10.1159/000424239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilkinson DS, Kirton V, Wilkinson JD. Perioral dermatitis. A 12-year review. Br J Dermatol. 1979;101(3):245–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1979.tb05616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coskey RJ. Perioral dermatitis. Cutis. 1984;34(1):55. 55-6,58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller WS. Tetracycline in the treatment of perioral dermatitis. N C Med J. 1971;32(11):471–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Veien NK, Munkvad JM, Nielsen AO, Niordson AM, Stahl D, Thormann J. Topical metronidazole in the treatment of perioral dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24(2 Pt 1):258–260. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bikowski JB. Topical therapy for perioral dermatitis. Cutis. 1983;31(6):678–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]