Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To provide background for physicians’ in-office assessment of medical fitness to drive, including legal risks and responsibilities. To review opinion-based approaches and current attempts to promote evidence-based strategies for this assessment.

QUALITY OF EVIDENCE

MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Ageline, and Sociofile were searched from 1966 on for articles on health-related and medical aspects of fitness to drive. More than 1500 papers were reviewed to find practical approaches to, or guidelines for, assessing medical fitness to drive in primary care. Only level III evidence was found. No evidence-based approaches were found.

MAIN MESSAGE

Three practical methods of assessment are discussed: the American Medical Association guidelines, SAFE DRIVE, and CanDRIVE.

CONCLUSION

There is no evidence-based information to help physicians make decisions regarding medical fitness to drive. Current approaches are primarily opinion-based and are of unknown predictive value. Research initiatives, such as the CanDRIVE program of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, can provide empiric data that would allow us to move from opinion to evidence.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Fournir aux médecins les notions nécessaires à l’évaluation au bureau de l’aptitude à conduire, sans oublier les risques et responsabilités légales. Examiner les stratégies proposées dans des articles d’opinion et les tentatives récentes pour promouvoir des stratégies d’évaluation fondées sur des données probantes.

QUALITÉ DES PREUVES

On a relevé les articles répertoriés dans MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsyINFO, Ageline et Sociofile depuis 1996, et portant sur les aspects médicaux et sanitaires de l’aptitude à conduire. Plus de 1500 articles ont été consultés pour repérer des stratégies pratiques ou des recommandations concernant l’évaluation médicale de l’aptitude à conduire en milieu de soins primaires. Les seules preuves trouvées étaient de niveau III. Aucune démarche fondée sur des données scientifiques n’a été identifiée.

PRINCIPAL MESSAGE

Trois méthodes d’évaluation sont ici discutées: les directives de l’American Medical Association, SAFE DRIVE et CanDRIVE.

CONCLUSION

Il n’existe pas d’information fondée sur des preuves pour aider les médecins à prendre des décisions concernant l’aptitude médicale à conduire. Les stratégies actuelles sont surtout basées sur des articles d’opinion et on ignore leur valeur prédictive. Des initiatives de recherche, comme le programme CanDRIVE des Instituts de recherche en santé du Canada, pourraient générer des données empiriques capables de nous faire passer du domaine de l’opinion à celui des données probantes.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

Family physicians find assessing fitness to drive difficult to do without jeopardizing their relationships with their patients. Testing for fitness is imprecise; physicians can assess operational skills, but not other aspects of driving ability, such as judgment.

Evidence behind tools used to assess fitness to drive is weak (level III). Three practical resources available are the SAFE DRIVE algorithm, the Ottawa Driving and Dementia Toolkit, and the CanDRIVE assessment acronym.

Family doctors can do first-line assessments, but should consider involving other specialized professionals, such as occupational therapists or on-the-road testing centres, in difficult cases.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Le médecin de famille trouve qu’il est difficile d’évaluer l’aptitude à conduire sans mettre en péril la relation avec son patient. L’évaluation de l’aptitude est imprécise; le médecin peut évaluer les habilités opérationnelles, mais non les autres aspects de l’aptitude à conduire, comme le jugement.

Les outils proposés pour évaluer l’aptitude à conduire reposent sur des preuves faibles (niveau III). On dispose toutefois de trois ressources pratiques: l’algorithme SAFE DRIVE, l’Ottawa Driving and Dementia Toolkit et l’acronyme d’évaluation CanDRIVE.

L’évaluation de base peut être faite par le médecin de famille, mais celui-ci devrait songer à recourir à des professionnels spécialisés comme les ergothérapeutes et, dans les cas difficiles, à des centres d’évaluation de la conduite sur route.

Old and young drivers have the highest rates of motor vehicle crashes (MVC) per kilometre driven; the lowest rates are found among middle-aged people.1,2 Young drivers crash primarily because they are inexperienced and take risks (eg, speeding, substance abuse). Reducing young drivers’ collision rates is not principally a medical issue: it requires legislative (eg, graduated licensing) and law-enforcement measures.

Older drivers crash for very different reasons. While most older drivers remain safe on the road, some suffer from the cumulative effects of medical conditions (eg, dementia, strokes, Parkinson disease) that eventually affect their fitness to drive.3 This article reviews the practical resources front-line physicians can use for in-office screening and assessment of medical fitness to drive.

Quality of evidence

The articles discussed in this paper were drawn from a computerized search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Ageline, and Sociofile from 1966 on for all articles on health-related and medical aspects of fitness to drive. The more than 1500 papers selected were reviewed to find practical approaches to, or guidelines for, screening and assessment of medical fitness to drive in front-line clinical settings. Only level III evidence (ie, expert opinion or consensus statements) was found. Due to the scarcity of definitive research in this area, the three practical approaches discussed (the American Medical Association [AMA] guidelines and the SAFE DRIVE and CanDRIVE approaches) are primarily based on consensus.

Legal responsibilities and risks

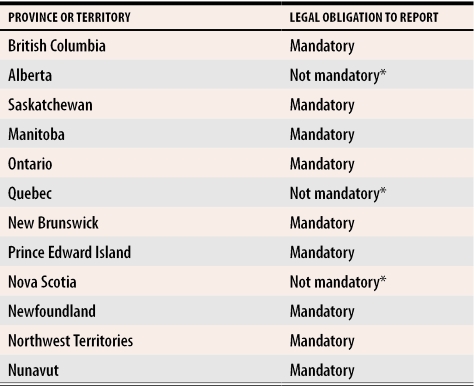

Reporting patients who have conditions that could affect driving ability is mandatory in many provinces. Physicians are usually protected from lawsuits resulting from such reporting (Table 1).

Table 1. Provincial and territorial regulations as of June 2004.

All provinces and territories offer legal protection to physicians who report patients they deem unfit to drive.

Compiled with the assistance of the Canadian Council of Motor Transportation Administrators and all 13 ministries of transportation.

*Physicians in Alberta, Quebec, and Nova Scotia can use their own judgment regarding reporting unsafe drivers to their ministries of transportation.

The concept “protection from lawsuits” is often misunderstood and requires clarification. It is still possible for patients or their families to file lawsuits. If a physician has followed the law with respect to reporting fitness to drive, it is extremely unlikely that he or she would lose such a lawsuit. Legal protection does not prevent patients and families from filing complaints with provincial medical colleges either. In Ontario, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO) would advise patients that physicians are merely following the law in sending a report to the provincial ministry of transportation.

If patients or their families still wish to pursue complaints, then in accordance with the Regulated Health Professions Act, the CPSO is required to investigate. Cases that might result in punitive action include situations in which physicians report people who are not their patients or patients who have not been examined. Similar rules and processes likely exist in other provinces. While physicians who have followed the law are protected from losing lawsuits and CPSO complaints, they could still suffer the emotional wear-and-tear that such lengthy review processes entail.

Physicians do, however, place themselves at risk of losing civil lawsuits if they fail to report unsafe drivers to the ministry of transportation and if these drivers are subsequently involved in MVCs.4,5 The outcome of such lawsuits might depend on the precise wording of each provincial statute regarding reporting patients who might be unfit to drive.

Other considerations

Another consideration in reporting fitness to drive is the negative effect on physician-patient and physician-family relationships. A survey by Marshall and Gilbert6 clearly demonstrated that physicians think reporting patients negatively affects these relationships. Patients and families might also suffer. Driving cessation leads to fewer out-of-home activities, social isolation, and worsening depression.7,8 As family and friends begin to help by driving patients to appointments, caregiver stress can increase.9 The negative effects of loss of driving privileges are more pronounced in rural communities.10-13

Physicians might also be reluctant to report patients who are currently unfit to drive but whose conditions might improve over time or whose driving abilities might improve with retraining. This reluctance is owing to the challenging and lengthy process of reinstating driver’s licenses once they have been suspended.

Finally, physicians’ ability to predict whether patients will become involved in MVCs is overestimated by licensing authorities and the general public. Several factors need to be taken into account.

Abilities can fluctuate, and patients’ presentation in physicians’ offices might not represent all periods during which they are driving. In some cases, fluctuation is related to medication or alcohol use.

Medical events that alter function can occur after visits to the office and cannot be predicted during the visit.

All active drivers are at some baseline risk of being involved in MVCs. Even if drivers pass all imaginable screening tests, they could still become involved in MVCs. This can be explained partly by factors extrinsic to drivers, such as weather, road conditions, and the behaviour of other drivers.

Physicians primarily assess operational skills (ie, basic motor, sensory, perceptual, and cognitive abilities required to drive safely). They rarely assess tactical decisions (ie, driving behaviour or style, choice of speed, and distance from the car in front) or strategic approaches (ie, planning and preparing for trips, self-restriction) that determine whether people can appropriately compensate for early or minimal loss of operational abilities.

Standard physical examinations were designed to detect presence or absence of disease, not to assess function.

Reliable, clinically sensible, and valid tools to assist clinicians in screening and assessment of fitness to drive do not exist.

The first three factors listed are irreversible and limit physicians’ ability to predict all MVCs. The next three factors can be addressed by devising and validating screening tools to better assess medical fitness to drive.

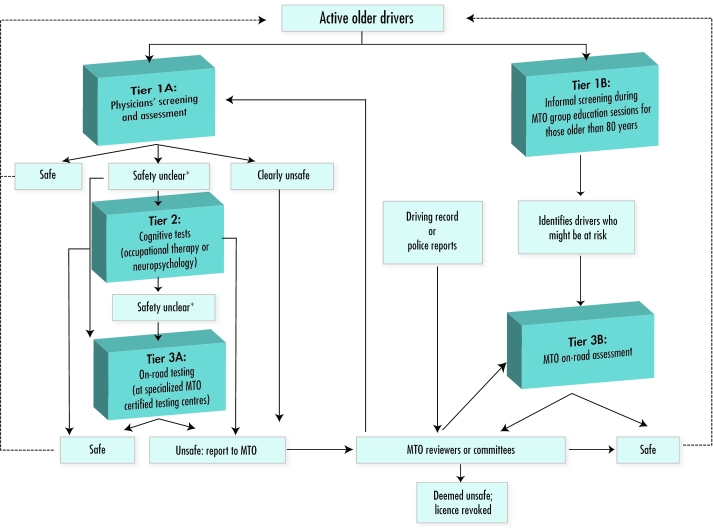

Given the disincentives and barriers listed above, it is not surprising that many physicians are reluctant to assess and report patients they think are unfit to drive. Are physicians the best professionals to assess fitness to drive? This question arises out of an understandable desire to avoid an extremely challenging medicolegal area. The question, however, also demonstrates a lack of understanding of the true role of physicians in this area and the tremendous potential to contribute to patients’ health and safety. The issue is not who can best assess fitness to drive but rather what complementary role can each profession play to improve road safety and decrease morbidity and mortality. Each profession is part of a system or network of assessments (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Assessment of fitness to drive in Ontario

MTO—Ministry of Transportation of Ontario.

*Drivers whose safety is unclear are reported to the MTO. Those with progressive diseases, such as dementia, require follow-up evaluations

Specialized assessment

Specialized driver assessment (ie, occupational therapy and neuropsychological office-based testing) and on-road testing do not replace physicians’ screening and assessment. There are too few occupational therapists and neuropsychologists to assess all older drivers every year. On-road testing remains the criterion standard for assessment, but is expensive ($300 to $600 per assessment) and is available only on a limited basis. It is unrealistic to think we could screen every older driver every year using on-road testing. Patients would not accept the need for such time-consuming and expensive annual assessments. Annual screening of large numbers of patients is best done by physicians in their offices. Borderline cases can be referred to specialized testing centres.

Research on simulators has not yet become widely available for clinical application. There is little or no consistency from simulator to simulator in terms of hardware, software, testing protocols, or pass-fail thresholds.

The disincentives and barriers to assessing fitness to drive also explain why at least one provincial medical association has lobbied for removal of the legal mandate to report unfit drivers (Table 1). While such reactions are understandable, they are difficult to justify ethically. It is hard to argue that a profession dedicated to improving patients’ health, safety, and quality of life should be allowed to divest itself of a responsibility vital to reducing patients’ morbidity and mortality.

To better meet professional and societal responsibilities, physicians need better screening and assessment tools. We should openly acknowledge that their ability to assess fitness to drive is currently limited. They cannot perform this task without evidence-based screening tools and without the support of other professionals (Figure 1).

Evidence-based screening tools

Developing validated evidence-based approaches is increasingly important because the medical conditions that affect ability to drive accumulate with age, older drivers are the fastest-growing segment of the active driving population, and older drivers suffer the highest rates of serious injury and death from MVCs.14-16 Several authors17-19 and national driving organizations,20 including Transport Canada, have called for development of instruments to aid physicians in determining fitness to drive.

In an article in this issue of Canadian Family Physician, Hogan (page 362) reviews published approaches to office-based assessment of older drivers. He found that evidence supporting these approaches is weak (level III). He recommends validation of all office-based approaches.

In addition to not being supported by research, the recommended approaches are often impractical. For instance, the “red flags for medically impaired driving” proposed by the AMA21 and reviewed by Hogan are overly inclusive and would likely identify most older patients in a family practice as requiring further assessment. The AMA’s “Patient Education Handout” is similar. Few older drivers would respond no to such statements as “other drivers drive too fast,” “busy intersections bother me,” “left-hand turns make me nervous,” and “I don’t like to drive at night.” The AMA suggests reviewing medications and doing a neuromuscular examination in evaluating fitness to drive,21 but does not indicate how the resulting information is to be used. For instance, the presence or absence of a medication is not important, but recent dose changes that could affect function are. The neuromuscular examination is not evidence based (ie, is not shown to predict crash risk) and does not provide thresholds at which patients would be at risk of MVCs. Hogan also reviewed the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) guide22 and found it was too broad to be of practical use.

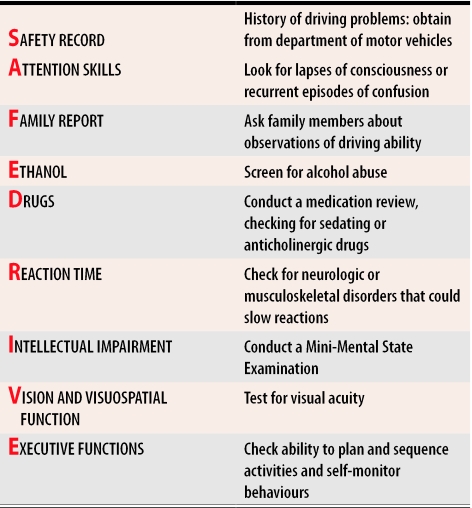

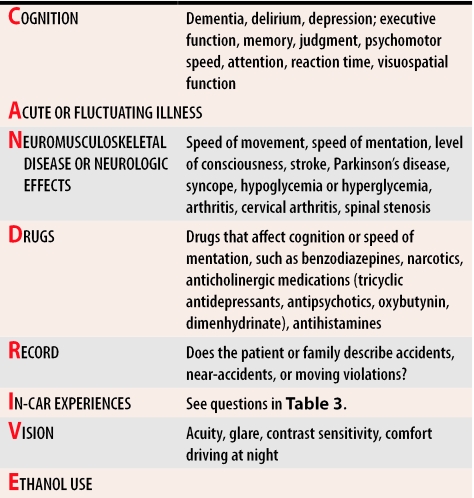

Given the lack of evidence-based screening tools and the serious shortcomings of the approaches reviewed by Hogan, what are front-line clinicians to do? They could selectively employ sections of the AMA, CMA, and SAFE DRIVE23 approaches (Table 223) (probably what most physicians do); they could examine other approaches being employed and studied by practising clinicians and researchers; and they could support and engage in research to devise and validate evidence-based screening tools to assess fitness to drive in primary care. In the remainder of this paper, we will review alternative approaches, such as the Ottawa Driving and Dementia Toolkit24 and the CanDRIVE assessment acronym, and introduce the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)–funded CanDRIVE research program25 that is dedicated to developing and validating evidence-based fitness-to-drive screening tools.

Table 2. SAFE DRIVE checklist.

If concerns are noted in any of these areas, referral to a specialized centre is recommended.

Adapted with permission from Wiseman and Souder.23

Ottawa Driving and Dementia Toolkit

In 1997, the Dementia Network of Ottawa developed a Driving and Dementia Toolkit24 for primary care physicians. The tool kit consists of background information on the topic, a list of local resources, the necessary forms to access these services, screening questions about older drivers’ safety, and the SAFE DRIVE approach23 (Table 223).

In 2001, the effectiveness of the tool kit in improving primary care physicians’ knowledge and confidence in addressing driving-related issues was evaluated.24 Responses to a multistage survey demonstrated that using the tool kit resulted in statistically significant improvements in physicians’ knowledge of driving issues and confidence in assessing fitness to drive.

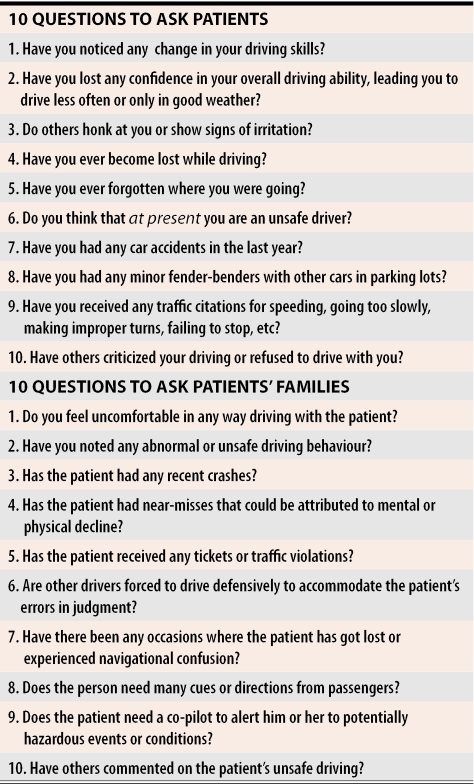

The tool kit also contains questions for older drivers and different questions for family members (Table 324). Questions for family members should be asked when patients are not present in order to maximize the honesty of responses. An on-line version of the full Driving and Dementia Toolkit and the SAFE DRIVE approach is available in the physicians’ resource section at http://www.candrive.ca.

Table 3. Driving and Dementia Toolkit interview questions.

Responses might not always reflect the full picture because patients and their families might want to preserve the privilege to drive.

Adapted from Byszewski et al.24

Much like the CMA, AMA, and SAFE DRIVE approaches, the Ottawa Driving and Dementia Toolkit questions are based on clinical acumen and consensus, but have not yet been validated to determine whether they truly predict risk of MVCs. The patient-directed questions (Table 324) are being examined in two studies supervised by the authors of this article. The tool kit is not yet an evidence-based tool.

CanDRIVE Assessment Acronym

An approach similar to the SAFE DRIVE algorithm is the CanDRIVE acronym (Table 4). Once again, this is not yet an evidence-based approach.

Table 4.

CanDRIVE assessment algorithm

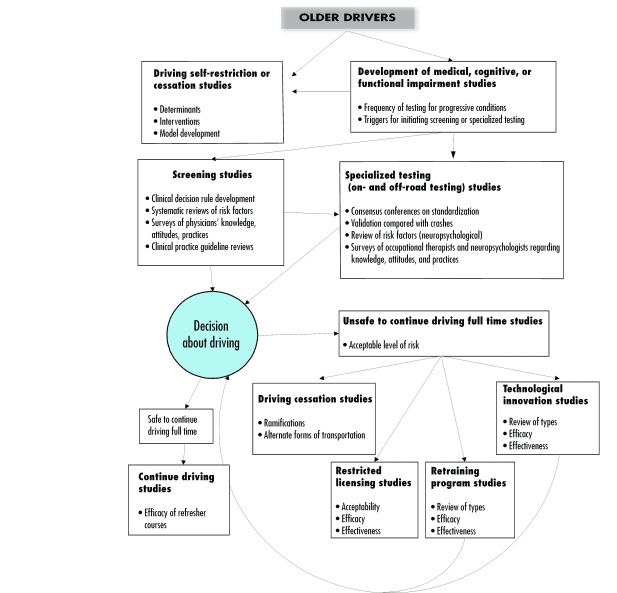

CanDRIVE research program

In March 2002, the CIHR’s Institute of Aging awarded a $1.25 million New Emerging Team grant to the CanDRIVE research group.25 The outline of related research projects of this national network is shown in Figure 2.25

Figure 2.

CanDrive program of research

One central project of the CanDRIVE research program is a large (N = 2000) prospective cohort study that will examine active older drivers annually and link results of their clinical assessments with their respective Ministry of Transportation driving records. Results of this study will allow derivation and validation of fitness-to-drive screening tools for front-line settings, such as physicians’ offices and Ministry of Transportation testing and licensing centres. The study will also try to validate specialized assessment approaches, such as occupational therapy and neuropsychological testing, and on-road assessment protocols. Multitiered assessment algorithms similar to the one shown in Figure 1 have been published, but do not accurately describe the situation in Canada.26

The large prospective cohort study could move assessment of fitness to drive from opinion to evidence. For this to become reality, the study will require the active support of provincial ministries of transportation; seniors’ associations; medical colleges, societies, and associations; and practising family physicians. To learn more about the CanDRIVE research program, visit http://www.candrive.ca.

Conclusion

Assessment of older people’s medical fitness to drive requires physicians to balance safety issues with the need for independence provided by operating a motor vehicle. All physicians have the ethical responsibility to reduce their older patients’ risk of injury from MVCs. In many provinces, they also have a legal obligation to do so. Unfortunately, there is little evidence to help physicians make decisions about fitness to drive.

Biography

Drs Molnar, Byszewski, Marshall, and Man-Son-Hing are members of CanDRIVE, a New Emerging Team funded by the Institute of Aging at the Canadian Institutes of Health Research at the Élisabeth-Bruyère Research Institute in Ottawa, Ont. Dr Molnar is a researcher in the CT Lamont Centre for Primary Care Research in the Elderly at the Élisabeth-Bruyère Research Institute. Drs Molnar, Byszewski, and Man-Son-Hing teach in the Division of Geriatric Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, at the University of Ottawa. Drs Molnar, Marshall, and Man-Son-Hing are affiliated with the Clinical Epidemiology Program at the University of Ottawa’s Health Research Institute. Dr Marshall teaches in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at the University of Ottawa. Drs Marshall and Man-Son-Hing serve on the Ontario Ministry of Transportation’s Medical Advisory Committee.

References

- 1.Reuban DB, Silliman RA, Traines M. The aging driver. Medicine, policy and ethics. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:1135–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb04403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cerrelli E. Older drivers; the age factor in traffic safety. Springfield, Va: National Technical Information Service; 1989. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker D, McDonald L, Rabbitt P, Sutcliffe P. Elderly drivers and their accidents: the Aging Driver Questionnaire. Accid Anal Prev. 2000;32(6):751–759. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(99)00125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capen K. New court ruling on fitness-to-drive issues will likely carry “considerable weight” across country. CMAJ. 1994;151(5):667. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capen K. Are your patients fit to drive? CMAJ. 1994;150(6):988–990. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall SC, Gilbert N. Saskatchewan physicians’ attitudes and knowledge regarding assessment of medical fitness to drive. CMAJ. 1999;160(12):1701–1704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marottoli RA, Mendes de Leon CF, Glass TA, Williams CS, Cooney LM, Jr, Berkman LF, et al. Driving cessation and increased depressive symptoms: prospective evidence from the New Haven EPESE. Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:202–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb04508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marottoli RA, de Leon CFM, Glass TA, Williams CS, Cooney LM, Jr, Berkman LF, et al. Consequences of driving cessation: decreased out of home activity levels. J Gerontol Soc Sci. 2000;55(Suppl B):334–340. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.6.s334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azad N, Byszewski A, Amos S, Molnar FJ. A survey of the impact of driving cessation on older drivers. Geriatr Today. J Can Geriatr Soc. 2002;5:170–174. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keplinger FS. The elderly driver: who should continue to drive? Phys Med Rehab: State of the Art Reviews 1998. 2002;12(1):147–155. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson JE. Older rural adults and the decision to stop driving: the influence of family and friends. J Community Health Nurs. 1998;15(4):205–216. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn1504_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holland CA. Self-bias in older drivers’ judgments of accident likelihood. Accid Anal Prev. 1993;25(4):431–441. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(93)90072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacKean JM, Elkington AR. Glaucoma and driving. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285(6344):777–778. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6344.777-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams AF, Carsten O. Driver age and crash involvement. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(3):326–327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.3.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans L. Older driver involvement in fatal and severe traffic crashes. J Gerontol. 1988;43(6):186–193. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.6.s186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Distiller LA, Kramer BD. Driving and diabetics on insulin therapy. S Afr Med J. 1996;86(8 Suppl):1018–1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nouri F. Fitness to drive and the general practitioner. Int Disabil Stud. 1988;10(3):101–103. doi: 10.3109/09638288809164122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller DJ, Morley JE. Attitudes of physicians toward elderly drivers and driving policy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:722–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb07460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parnes LS, Sindwani R. Impact of vestibular disorders on fitness to drive: a census of the American Neurotology Society. Am J Otol. 1997;18(1):79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators. Maturing drivers workshop and proceedings and aging driver strategy. Ottawa, Ont: Transport Canada; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang CC, Kosinski CJ, Schwartzberg JG, Shanklin AV. Physician’s guide to assessing and counseling older drivers. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canadian Medical Association. Determining medical fitness to drive. A guide for physicians. 6th ed. Ottawa, Ont: Canadian Medical Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiseman EJ, Souder E. The older driver: a handy tool to assess competence behind the wheel. Geriatrics. 1996;51:36–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byszewski AM, Graham ID, Amos S, Man-Son-Hing M, Dalziel BD, Marshall SM, et al. A continuing medical education initiative for Canadian primary care physicians: the Driving and Dementia Toolkit: a pre- and post-evaluation of knowledge, confidence gained, and satisfaction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1484–1489. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Man-Son-Hing M, Marshall SC, Molnar FJ, Wilson KG, Crowder C, Chambers LW. [cited 2005 January 5];A Canadian research strategy for older drivers: the CanDRIVE program. Geriatr Today. 2004 7:86–92. Available at: http://www.canadiangeriatrics.com.

- 26.Janke MK. Medical conditions and other factors in driver risk. Sacramento, Calif: California DMV, Research and Development Section; 2001. [Google Scholar]