Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To assess the current prevalence of depression and anxiety among Ontario family medicine residents, and to describe their coping strategies.

DESIGN

Surveys mailed to residents integrated DSM-IV diagnostic criteria and a previously validated Patient Health Questionnaire.

SETTING

Ontario family medicine programs from June to August 2002.

PARTICIPANTS

Residents entering, advancing in, or graduating from residency programs: approximately 216 yearly for a total of 649 residents.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Types and frequency of coping skills used by residents; prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders.

RESULTS

Response rate for residents entering programs was 46% and for graduating residents was 30% (37% response rate overall). Prevalence of depressive disorders was 20% (13% major depressive disorders, 7% other depressive syndromes)(odds ratio [OR] 3.4, confidence interval [CI] 2.7 to 7.5, P <.001). Prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder was 12%, and 2% of residents met criteria for panic syndrome (OR 4.3, CI 1.6 to 11.8, P =.002). Rates were similar for men and women. Medical training was commonly identified as a negative influence on the mental health of troubled residents.

Residents most often turned to family and friends when they needed help (43.7% of respondents). About 17.3% saw their family doctors, 15.4% counselors, and 7.9% psychiatrists. Some residents (13.4%) used medication to deal with their affective symptoms, 7.1% underwent cognitive-behavioural therapy, and 8.3% required a leave of absence from their programs.

More than half (61.8%) indicated recreational use of alcohol and drugs, 1.2% identified use due to addiction, and 5.9% used drugs to help cope with their problems. Four respondents admitted concern that they might commit suicide during residency; a different three had made previous attempts.

CONCLUSION

Affective disorders (both depression and anxiety syndromes) are three to four times more common among Ontario family practice residents than in the general population; male and female residents are equally affected. Most residents with these problems report negative effects on their function at work. Medical training is the most commonly identified negative influence on mental health. While residents most often obtain help from family members and friends, many seek professional help.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Déterminer la prévalence actuelle de la dépression et de l’anxiété chez les résidents en médecine familiale de l’Ontario et décrire les stratégies qu’ils développent pour y faire face.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Les enquêtes postées aux résidents incluaient les critères diagnostiques du DSM-IV et un questionnaire précédemment validé sur la santé des patients.

CONTEXTE

Programmes ontariens de médecine familiale, de juin à août 2002.

PARTICIPANTS

Résidents en début, milieu ou fin du programme de résidence: environ 216 par année, pour un total de 649 participants.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES À L’ÉTUDE

Types et fréquence des stratégies développées par les résidents; prévalence des problèmes d’anxiété et de dépression.

RÉSULTATS

Le taux de réponse était de 46% pour les résidents en début de programme et de 30% pour ceux qui terminaient (taux de réponse global de 37%). La prévalence de la dépression était de 20% (13% de dépressions majeures, 7% d’autres syndromes dépressifs) (rapport des cotes [RC] 3,4, intervalle de confiance [IC] 2,7 à 7,5, P <.001). La prévalence des troubles anxieux généralisés était de 12%, et 2% des participants répondaient aux critères du syndrome de panique (RC 4,3, IC 1,6 à 11,8, P =.002). Les taux étaient semblables dans les deux sexes. Les résidents affectés considéraient souvent que la formation médicale avait une influence négative sur leur santé mentale.

Les résidents ont souvent cherché du secours auprès de leurs amis ou parents (43,7% des répondants). Environ 17,3% se sont adressés à leur médecin de famille, 15,4% à un conseiller et 7,9% à un psychiatre. Quelques-uns (13,4%) ont eu recours à une médication pour mieux contrôler leurs symptômes affectifs, 7,1% ont entrepris une thérapie cognitivo-comportementale et 8,3% ont dû s’absenter de leur programme.

Plus de la moitié (61,8%) ont déclaré avoir fait un usage récréatif d’alcool et de drogues, dont 1,2% par addiction, et 5,9% prenaient des drogues pour mieux face à leurs problèmes. Quatre répondants ont dit avoir été préoccupés par l’idée d’un suicide éventuel pendant leur résidence; trois autres avaient déjà fait des tentatives.

CONCLUSION

Les problèmes affectifs (syndromes dépressifs et anxieux) sont trois à quatre fois plus fréquents chez les résidents en médecine familiale de l’Ontario que dans la population générale; les deux sexes sont également affectés. La plupart des résidents touchés déclarent que cela a une influence négative sur leur rendement au travail. Parmi les facteurs qui influencent négativement la santé mentale, le plus souvent mentionné est la formation médicale. Même si les résidents obtiennent le plus souvent de l’aide de leurs parents et amis, plusieurs consultent aussi des professionnels.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

Depression and anxiety affective disorders appear to be three to four times more prevalent among Ontario family medicine residents than in the general population.

Most residents with mental health problems report that these problems have a negative effect on their medical work and studies.

Residents often turn to family and friends for help, but many seek professional help.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Les troubles affectifs de types anxieux et dépressif semble être trois à quatre fois plus fréquents chez les résidents en médecine familiale d’Ontario que dans la population générale.

La plupart des résidents présentant des problèmes de santé mentale déclarent que ces affections ont un effet négatif sur leurs activités médicales et sur leurs études.

Les résidents cherchent souvent de l’aide auprès de leurs amis ou parents, mais plusieurs s’adressent à des professionnels.

Mental illness among Canadian medical trainees is an important and largely unexplored component of Canada’s medical culture. No studies focusing on family medicine residents’ mental illnesses have been undertaken in nearly 20 years. Data gathered from general medical trainees demonstrate a range of mental health assessments.

A MEDLINE search for English-language articles was undertaken using the search words mental health, stress (psychological), anxiety, depression, and “internship and residency” back to 1975. While annual incidence of major depressive disorders in the general population is estimated at 6%,1 the international literature indicates it ranges among medical trainees from 15% to 30%.2,3,4,5 A 1990 survey3 of 800 American medical students and residents found a 40% prevalence of anxiety or depressive symptoms in female medical students and residents and a 27% prevalence among male trainees.

In 1987, the Professional Association of Internes & Residents of Ontario (PAIRO) surveyed6 its 2143 members and found 23% of respondents suffered some depressive symptoms (most mild to moderate), with more symptoms among female residents. In 1997, 621 medical students, 645 residents, and 415 graduate students from Calgary, Alta; Edmonton, Alta; Halifax, NS; and Hamilton, Ont, responded to a survey.7 It documented a “mild stress level,” higher among female medical trainees, but generally lower than among a comparison group of graduate students. Both groups had more symptoms than the general population.

Several studies offer conflicting results. A 1992 Beck inventory survey8 of 178 family practice residents in South Carolina demonstrated “better than average psychological health” according to age-adjusted norms. A survey2 in 1988 of 61 first-year residents in Wisconsin showed a depression rate of 15.5%; the rate in a sample of nonmedical university undergraduates was 23.5%.

Residents cope with mental illness in various ways. A previous survey of 76 Ontario family practice residents showed that up to 40% turn to family, friends, or fellow residents for support.9 In 1991, 30% to 60% of 113 American specialty (anesthesia, pediatrics, psychiatry) residents surveyed indicated they would access psychotherapy if it were offered.5 Residents’ coping mechanisms are not always positive. Documented use of alcohol and substance abuse ranges from 2% to 16%.2,9 In the PAIRO survey, 65% of moderately depressed trainees sought no help.6

Generalized anxiety disorder is less well studied in medical training and is estimated to affect 3% of the nonmedical general population.10

This study was designed to assess coping skills and to provide a current estimate of the prevalence of depression and anxiety among Ontario family medicine residents.

METHODS

We developed a three-page survey on depression and anxiety symptoms, using DSM-IV criteria, modeled on the Patient Health Questionnaire, the most current instrument validated for primary care.11 Questions were added to assess prevalence of anxiety, coping and treatment resources, suicide and substance abuse issues, and need for leave of absence from training. The questionnaire was pilot-tested on residents in the first year of the Thunder Bay family medicine residency program. Final surveys were mailed from June to August 2002 to 649 entering, advancing, and graduating Ontario family medicine residents (approximately 216 residents per year).

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. To identify sex differences in results, chi-square tests were performed. Ethics approval was obtained from the Lakehead University research Ethics Board.

RESULTS

An overall 37% response rate included 254 surveys, 164 from female respondents, 90 from male respondents. Mean age of respondents was 29. Response rate was 46% among respondents entering family medicine residency, but fell to 30% among graduating residents entering the work force. Prevalence of major depression was 13%, of other depressive syndromes was 7%; combined prevalence was 20% for any depressive syndrome.

Generalized anxiety syndrome was reported by 12% of residents, and 2% met the criteria for panic syndrome.

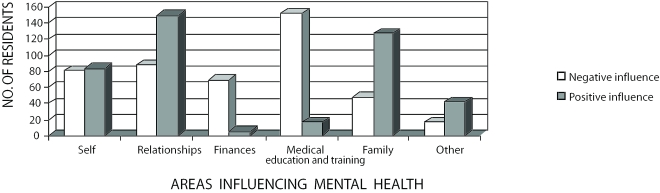

Rates among men and women were not significantly different. Among graduating participants, affective disorders increased during the clinical years of training. Medical training was identified as the most difficult area of life for troubled residents who found it “somewhat difficult to function” (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Positive and negative influences on mental health

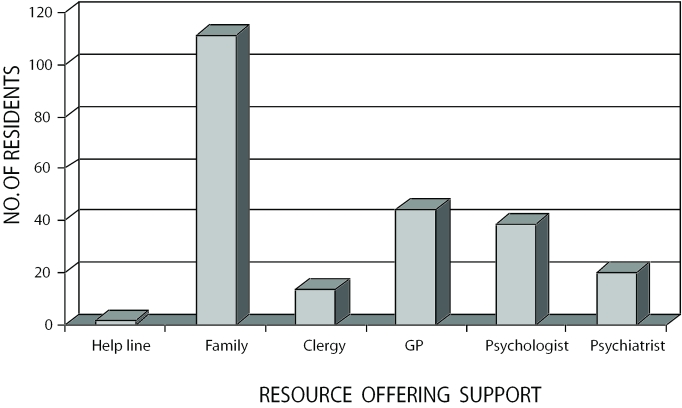

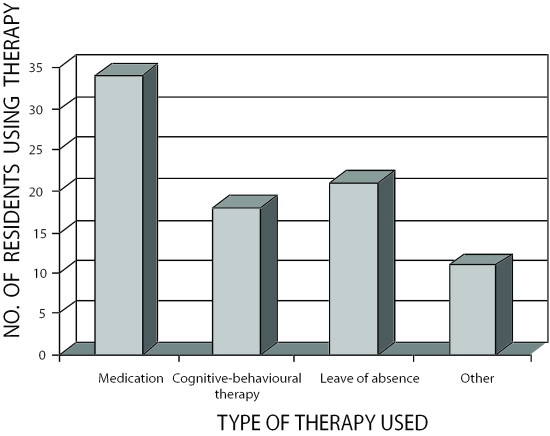

Residents most often turned to family and friends when they needed help (43.7% of respondents). Some (17.3%) visited their family physicians; 15.4% saw a counselor or psychologist; and 7.9% saw a psychiatrist (Figure 2). Among respondents, 13.4% had used a medication to deal with their affective symptoms, 7.1% underwent cognitive-behavioural therapy, and 8.3% took a leave of absence (Figure 3). With respect to alcohol and drug use, 61.8% indicated recreational use, 1.2% indicated use due to addiction, and 5.9% used drugs to help deal with their problems. Four responded yes to the question, “Are you worried you might commit suicide during residency training?” A different three respondents indicated a past suicide attempt.

Figure 2.

Resources accessed by residents

Figure 3.

Residents’ use of therapies

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of depressive disorders in our study was comparable to others in the medical literature, indicating far greater levels of these disorders among family medicine residents than in the general population. Major depression is significantly higher among medical trainees than in the general Ontario population (OR 3.4, CI 2.7-7.5, P<.001).

This study also provides clear new information about levels of anxiety among family practice residents. Generalized anxiety syndrome is significantly more prevalent among medical trainees than in the general population (P =.002), with an OR of 4.3 (CI 1.6 to 11.8).

A notable percentage (8.3%) of family practice residents require time away from their training programs because of their mental health problems. This has implications for program policy and administration.

While informal aid is most often sought, a substantial proportion of residents seek professional help. Family practice programs should ensure their residents have confidential and timely access to independent family physicians, psychologists, and psychiatrists.

The study was retrospective and was subject to both response and recall biases. Perhaps residents were more likely to respond if they had experienced mental health problems. Recall of symptoms could have been magnified or minimized. Underreporting is also possible; respondents with mental health issues could have had concerns about the stigma attached to such issues. This questionnaire is the first in the literature to incorporate DSM-IV standardized criteria.

Unfortunately, the overall response rate was lower than we had hoped. The survey was timed for a June to August distribution to capture three cohorts of residents. Unfortunately, the graduating year’s residents had a poor response rate, which affected the overall rate. We presumed they were busy moving and preparing for entry into the family medicine work force.

Reports in the literature suggest family practice residents take more leave of absence and less medication for mental health problems than do internal medicine residents. Differences between specialty programs and family medicine, and among programs, need to be further studied so that all residents have the same supports for dealing with what is a common and serious issue. Future efforts might address causes of affective disorders in medical training.

CONCLUSION

Affective disorders (both depression and anxiety syndromes) are three to four times more common among Ontario family practice residents than in the general population; male and female residents are equally affected. Most residents with these problems report negative effects on their function at work. Medical training is the most commonly identified negative influence on mental health. While residents most often obtain help from family members and friends, many seek professional help.

Biographies

Dr Earle is a resident in the Family Medicine North Program in Thunder Bay, Ont.

Dr Kelly is an Associate Clinical Professor in the Family Medicine North Program and in the Family Medicine Department at McMaster University in Sioux Lookout, Ont.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Parkih SV, Wasylenki D, Goering P, Wong J. Mood disorders: rural/urban differences in prevalence, health care utilization, and disability in Ontario. J Affect Disord. 1996;38:57–65. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirsling RA, Kochar MS. An evaluation of mood states among first-year residents. Psychol Rep. 1989;65:355–366. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1989.65.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendrie HC, Clair DK, Brittain HM, Fadul PE. A study of anxiety/depressive symptoms of medical students, house staff, and their spouses/partners. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990;178(3):204–207. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199003000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruben DB. Depressive symptoms in medical house officers. Rhode Island Hospital. Providence, RI: Rhode Island Hospital; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samuel SE, Lawrence JS, Schwartz HJ, Weiss JC, Seltzer JL. Investigating stress levels of residents: a pilot study. Med Teach. 1991;13(1):89–92. doi: 10.3109/01421599109036762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu K, Marshall V. Prevalence of depression and distress in a large sample of Canadian residents, interns, and fellows. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1561–1566. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.12.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toews JA, Lockyer JM, Dobson DJG, Simpson E, Brownell AK, Brenneis F, et al. Analysis of stress levels among medical students, residents and graduate students at four Canadian schools of medicine. Acad Med. 1997;72(11):997–1002. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199711000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Godenick MT, Musham C, Palesch Y, Hainer BL, Michels PJ. Physical and psychological health of family practice residents. Fam Med. 1995;27:646–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudner HL. Stress and coping mechanisms in a group of family practice residents. J Med Educ. 1985;60:564–566. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198507000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rizzo R, Piccinelli M, Mazzi MA, Bellantuono C, Tansella M. The personal health questionnaire: a new screening instrument for detection of ICD-10 depressive disorders in primary care. Psychol Med. 2000;30:831–840. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]