Abstract

Participants in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study were randomly assigned to receive daily antioxidants (vitamin C, 500 mg; vitamin E, 400 IU; beta carotene, 15 mg), zinc and copper (zinc, 80 mg; cupric oxide, 2 mg), antioxidants plus zinc and copper, or placebo. A cognitive battery was administered to 2,166 elderly persons after a median of 6.9 years of treatment. Treatment groups did not differ on any of the six cognitive tests (p > 0.05 for all). These results do not support a beneficial or harmful effect of antioxidants or zinc and copper on cognition in older adults.

More than 33% of women and 20% of men aged >65 years are estimated to develop dementia, and many more may develop a milder form of cognitive impairment. Therefore, the development of preventive strategies to reduce or delay onset of cognitive impairment is critical.

Oxidative pathways are hypothesized to be involved in the etiology of Alzheimer disease (AD) and vascular dementia, the two most common forms of dementia. Several observational studies of nondemented older adults have suggested that high antioxidant dietary intake or the use of antioxidant supplements is associated with better cognitive performance.1,2

In addition to antioxidants, the impact of other nutrients, such as zinc and copper, on cognitive performance is unclear. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) provides an opportunity to assess cognitive performance in older adults randomly assigned to receive standardized doses of antioxidants, zinc and copper, antioxidants plus zinc and copper, or placebo for an average of nearly 7 years.

Methods

Study population

AREDS is a large, multicenter study designed to improve the understanding of the course and prognostic factors of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). A large randomized trial was also conducted as part of AREDS to determine the effect of antioxidants and zinc on the progression of AMD. Between 1992 and 1998, 11 clinical centers enrolled 3,640 participants who were categorized into AMD categories. In the trial, participants were randomly assigned to receive daily oral tablets containing 1) antioxidants (500 mg vitamin C, 400 IU vitamin E, and 15 mg beta carotene); 2) 80 mg zinc as zinc oxide and 2 mg copper as cupric oxide; 3) antioxidants plus zinc and copper; or 4) placebo. The main results of the AMD trial have been published and suggest a benefit of antioxidants and zinc in reducing progression of AMD for those at risk.3

Cognitive function

Of the 3,640 AMD trial participants, 2,166 (60%) completed the AREDS cognitive battery near the end of the trial. Of the 1,474 participants without cognitive testing, 330 died before the implementation of the cognitive study, and 1,144 refused or were otherwise unable to participate. Participants without cognitive testing were more likely to be older, have more ocular abnormalities, and be less educated compared with those participating in the ancillary study (p < 0.01).

The AREDS cognitive function battery included six validated cognitive tests with eight components: 1) The Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS); 2) Animal Category; 3) Letter Fluency; 4) Logical Memory Part I and 5) Logical Memory Part II, Wechsler Memory Scale Revised; 6) Immediate Recall and 7) Word List Mean; Buschke Selective Reminding Test; and 8) Digits Backwards.

Other measurements

At the beginning of the trial, we obtained demographic information and conducted a general physical examination, including standardized measurement of height, weight, and blood pressure. We assessed dietary intake during the year before randomization using a modified Block Food Frequency Questionnaire. At the time of administration of the cognitive function battery, depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of the participants receiving cognitive testing were compared across treatment groups using analysis of variance for continuous variables and χ2 for dichotomous variables. Bivariate associations of the cognitive scores were assessed using generalized linear models. Logistic regression was used to investigate the effect of supplementation on the likelihood of having cognitive impairment (3MS score, <80).

Results

The 2,166 participants included in this study had a mean age of 75 ± 5 years (range, 61 to 87 years) at the time of the AREDS cognitive battery administration. There were no significant differences by treatment group among baseline characteristics (including age, sex, race, education, AMD category, smoking, hypertension, body mass index, history of diabetes or coronary disease, CES-D score, use of antihypertensive medications, and use of aspirin).

Mean cognitive scores on all eight parts of the six tests were not statistically different across the four treatment groups (table). The results were similar after covariate adjustment. Similarly, there were no significant differences on cognitive scores comparing participants who were randomly assigned to receive zinc (and copper) with those not assigned to zinc, or on cognitive scores comparing participants randomly assigned to receive antioxidants with those not assigned to antioxidants. Covariate adjustment did not change the results.

Table.

Cognitive test scores by treatment group

| Treatment group

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive test | Antioxidants, n = 566 | Antioxidants + zinc, n = 528 | Zinc, n = 538 | Placebo, n = 534 | p Value* |

| Logical memory | |||||

| Part I, immediate recall | 36.3 (10.9) | 35.5 (11.4) | 37.1 (10.9) | 35.6 (10.9) | 0.06 |

| Part II, delayed recall | 20.9 (8.4) | 20.6 (8.8) | 21.3 (8.8) | 20.6 (8.5) | 0.46 |

| 3MS | 92.7 (6.7) | 92.5 (6.1) | 92.7 (6.3) | 92.1 (6.9) | 0.40 |

| Letter fluency | 39.5 (13.5) | 37.9 (13.0) | 38.7 (13.4) | 37.6 (13.6) | 0.09 |

| Animal category | 17.3 (5.0) | 16.8 (4.7) | 17.2 (4.9) | 16.9 (4.9) | 0.23 |

| Buschke test | |||||

| Immediate recall | 26.1 (13.0) | 26.9 (12.8) | 26.1 (12.6) | 25.7 (13.2) | 0.50 |

| Word list mean | 5.8 (2.1) | 5.8 (2.1) | 5.8 (2.2) | 5.7 (2.3) | 0.88 |

| Digits backwards | 6.3 (1.9) | 6.2 (1.8) | 6.2 (1.9) | 6.3 (1.9) | 0.78 |

Results expressed as mean (SD).

p Value from generalized linear model.

3MS = Modified Mini-Mental State Examination.

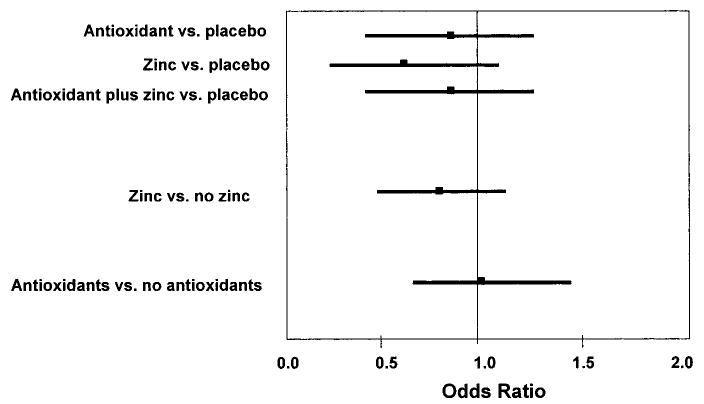

Ninety-seven (4.5%) of the participants met criteria for cognitive impairment (3MS score, <80). There was no significant effect of treatment group on likelihood of having cognitive impairment (figure). A trend toward slight benefit of zinc was found to be not significant. These results were similar after covariate adjustment.

Figure.

The likelihood (odds ratio and 95% CI) of developing cognitive impairment (Modified Mini-Mental State Examination score, <80) in the 2,166 Age-Related Eye Disease Study participants. Reference group is placebo (no active treatment).

Discussion

This large, randomized controlled trial examined the effect of treatment with antioxidants or zinc and copper on cognitive function in nondemented elderly adults. Compared with placebo treatment, antioxidants with or without zinc and copper did not have a significant effect on cognitive performance at the end of the trial. There also were no significant differences in the likelihood of having cognitive impairment, as assessed by the 3MS, across all treatment groups.

Our results stand in contrast to those from several observational studies that have reported a beneficial effect of either antioxidant supplements or dietary intake on cognitive function or risk of dementia in the elderly population.1,4,5 However, other observational studies have not observed a protective effect of antioxidant supplement use and cognitive outcomes in elderly persons.6,7

A randomized controlled trial of vitamin E for the management of AD demonstrated a reduced risk of dementia severity, death, or being placed in a nursing home in the group assigned to 2,000 IU of vitamin E daily. However, there was no improvement on cognitive test scores in the treated group.8 Our results are consistent with that trial in that we also did not find a benefit of antioxidants on cognitive scores. However, we did not find any association with antioxidant treatment and likelihood of having cognitive impairment. This may be because of differences in antioxidant doses (e.g., 400 IU of vitamin E compared with 2,000 IU) or because of our patient population being nondemented and having more intact cognitive abilities.

Other studies have reported that high levels of zinc9 induce β-amyloid to form clumps resembling the amyloid plaques seen in AD and that patients with AD have higher serum levels of copper compared with control subjects.10 Our finding of no harmful effect on cognitive function of high-dose zinc supplementation along with 2 mg of copper in the AREDS population is reassuring, especially because many patients with AMD are now treated with this combination.

Cognitive function was not the primary outcome of our study, and this has led to a number of study limitations. The cognitive testing occurred at the end of the trial; therefore, we can only assess the cross-sectional comparison of treatment groups, and thus we cannot determine whether antioxidant or copper and zinc treatment influences the rate of cognitive decline. Randomization to the various treatment groups, which resulted in equivalence of the treatment groups in a large number of baseline characteristics, is likely, but not definitely, to lead to equal variation of cognitive function in each treatment group. Another limitation is that not all participants in the trial had cognitive testing, although participation in the cognitive ancillary study did not differ by treatment group and so probably does not interfere with our assessment of treatment effects. We also cannot be certain that our results pertain to older adults without eye disease, although there is no biologic explanation why these groups would respond differently to treatment.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

AREDS Report No. 12.

Additional material related to this article can be found on the Neurology Web site. Go to www.neurology.org and scroll down the Table of Contents for the November 9 issue to find the title link for this article.

Writing Team: Kristine Yaffe, MD, Departments of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Epidemiology, University of California, San Francisco, and San Francisco VA Medical Center, CA; and Traci E. Clemons, PhD, Wendy L. McBee, MA, and Anne S. Lindblad, PhD, The EMMES Corporation, Rockville, MD.

A complete list of the members of the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) Research Group is available on the Neurology Web site at www.neurology.org (Appendix E-1).

The Writing Team for this report and the AREDS investigators have no commercial or proprietary interest in the supplements used in this study.

Supported by contracts from the National Eye Institute and the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD, with additional support from Bausch & Lomb Inc, Rochester, NY.

References

- 1.Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, et al. Dietary intake of antioxidant nutrients and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease in a biracial community study. JAMA. 2002;287:3230–3237. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.24.3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masaki KH, Losonczy KG, Izmirlian G, et al. Association of vitamin E and C supplement use with cognitive function and dementia in elderly men. Neurology. 2000;54:1265–1272. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.6.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS Report No. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1417–1436. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Ruitenberg A, et al. Dietary intake of antioxidants and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2002;287:3223–3229. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.24.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zandi PP, Anthony JC, Khachaturian AS, et al. Reduced risk of Alzheimer disease in users of antioxidant vitamin supplements: the Cache County Study. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:82–88. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luchsinger JA, Tang MX, Shea S, Mayeux R. Antioxidant vitamin intake and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:203–208. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendelsohn AB, Belle SH, Stoehr GP, Ganguli M. Antioxidant supplement use and its association with cognitive function in an elderly, rural cohort: the MoVIES project. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:38–44. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas RG, et al. A controlled trial of selegiline, alpha-tocopherol, or both as treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1216–1222. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704243361704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bush AI, Pettingell WH, Multhaup G, et al. Rapid induction of Alzheimer A beta amyloid formation by zinc. Science. 1994;265:1464–1467. doi: 10.1126/science.8073293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Squitti R, Lupoi D, Pasqualetti P, et al. Elevation of serum copper levels in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 2002;59:1153–1161. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.8.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.