Smoking was first introduced into the United Kingdom in the late 16th century. Shortly afterwards, King James I of England implemented the first tax on tobacco use. He also published his famous A Counterblaste to Tobacco in 1604, where he reflected on his dislike of the “precious stink” and observed: “Smoking is a custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs, and in the black, stinking fume thereof nearest resembling the horrible Stygian smoke of the pit that is bottomless.”

Figure 1.

King James I of England, by John de Critz the Elder (c1552-1642). King James I implemented the first tax on tobacco

Cigarette smoking delivers nicotine—a powerfully addictive drug—quickly and in high doses directly to the brain. Addiction to nicotine is usually established through experimentation with cigarettes during adolescence and often results in sustained or lifelong smoking. However, nicotine itself does not cause major health problems in most users; it is the accompanying tar that accounts for most of the harm caused by cigarettes.

Figure 2.

Warnings found on cigarette boxes are useful ways in which to remind individuals of the dangers of smoking

Effects of cigarette smoking

Apart from being the most common and important cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cigarette smoking causes a range of other chronic diseases and cancers affecting almost every bodily system. Cigarette smoking results in more than 100 000 deaths each year in the United Kingdom. Some diseases—including sarcoidosis, extrinsic allergic alveolitis, Parkinson's disease, and ulcerative colitis—are less common in smokers.

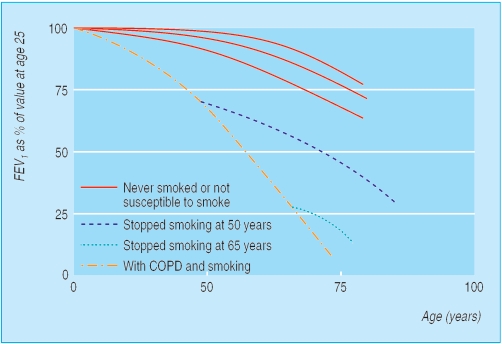

Figure 3.

Stopping smoking at any age has beneficial effects on the lung function of patients with COPD

Primary prevention of COPD

As long as cigarette smoking remains a normal and acceptable behaviour in adults, preventing children and adolescents from experimenting is difficult. However, measures to reduce children's access to cigarettes will probably help prevent smoking. The most effective approach to primary prevention is the application of general population measures that reduce incentives to smoke in both adults and young people. Examples include

Comprehensive bans on advertising and promotion

Sustained increases in real price

Policing of illegal sources of less expensive cigarettes

Comprehensive smoke-free policies at work and public places

Health warnings on cigarette packs

Sustained health promotion campaigns.

By preventing smoking, all of these measures will reduce the incidence of COPD.

Secondary prevention of COPD

Smoking cessation is the most effective means of secondary prevention for COPD. At any age it reduces disease progression and reduces the rate of decline in lung function in those with established COPD to that of a non-smoker. Individuals with COPD who quit smoking experience a substantial improvement in overall health, functional status, and survival, as well as a reduced incidence of many forms of cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Thus, it is important to emphasise to all patients with COPD that it is never too late to stop smoking.

This is the fourth in a series of 12 articles

Successful and cost effective smoking cessation interventions have been available for many years. These include generic population measures to encourage smoking cessation (and to discourage uptake of smoking) as mentioned above, plus individual interventions involving behavioural support and pharmacotherapy.

Figure 4.

Verbal and written smoking cessation advice should be given to all current smokers at all available opportunities

Helping patients stop smoking

Behavioural support

All health professionals should encourage all smokers to quit at every available opportunity. Always offer advice in an encouraging, non-judgmental, and empathetic manner. Explain to patients with COPD who still smoke that stopping is not easy and that several attempts may be required to achieve long term success. Find out if they are motivated to stop and, if so, support a quit attempt as soon as possible.

Figure 5.

A variety of pharmacological preparations are available to help patients quit smoking

If they are not motivated, explore their reasons for not quitting and encourage them to consider doing so in the future. Introduce the idea that a cigarette is a killer and should not be regarded as a “comforting friend” in times of anxiety and stress. Explain that cigarette smoking is pleasurable or relaxing primarily because it relieves withdrawal symptoms—remind patients of their first experience of smoking and ask if it was pleasant. List the harmful chemicals and carcinogens that are found in cigarettes (such as benzene and arsenic) and all the diseases that smoking causes.

Table 1.

Brief advice on smoking cessation

| • Brief advice from health professionals should be given to all smokers. Doing so causes 2-3% of smokers to become long term abstainers and is probably the most cost effective clinical intervention |

| • “The best thing you can do for your health is to stop smoking, and I advise you to stop as soon as possible. The sooner you stop the better.” |

| • “How do you feel about your smoking?” |

| • “How do you feel about tackling your smoking now?” |

Highlight the importance of behavioural support and pharmacotherapy, and encourage patients to use both. Discuss potential nicotine withdrawal symptoms and explain that these are at their worst in the first few days and most will pass within about a month. Weight gain is often a concern, so emphasise the need to eat healthily, drink water before meals, and exercise. Formal dietary advice may be necessary for some individuals. Encourage patients to create goals and rewards for themselves, and highlight the financial benefits of stopping smoking. Devise coping mechanisms to use during periods of craving. Give written information to support your advice so that the risks of smoking and the benefits of quitting can be reinforced at home by family members.

Table 2.

Behavioural strategies for smoking cessation

| • Set a quit date and tell friends and colleagues that you are quitting |

| • Prepare by avoiding smoking in places where you spend a lot of time |

| • Get rid of all cigarettes |

| • Don't “cut down” or “have the odd one”-aim for total abstinence |

| • Review past attempts; look at what has helped and what hasn't |

| • Anticipate challenges and think of ways of dealing with them |

| • Encourage partners to quit at the same time and offer them support |

| • Use nicotine replacement therapy or bupropion |

| • Make use of follow-up support |

Deliver behavioural advice yourself or ask a smoking cessation specialist to do it for you. Arrange to review all patients, either personally or through a smoking cessation specialist, soon after their quit attempt. Use this review to monitor progress, use alternative strategies if necessary, and provide support and encouragement.

Nicotine replacement therapy

Nicotine replacement is the most common drug treatment to help smoking cessation and increases the chances of quitting by about 1.7-fold. It works by supplying nicotine without the toxic components of cigarette smoke. Many smokers believe that nicotine is toxic, so emphasise that nicotine is safe; it is the tar that kills.

Nicotine replacement therapy is available in many different formulations. Although some forms (gum, inhalator, nasal spray, and lozenges) deliver nicotine more quickly than others (transdermal patches), all deliver a lower total dose and deliver it to the brain more slowly than does a cigarette. Since there is no clear evidence that any formulation is more effective than another, the best approach is to follow individual patients' preference over choice of product. For heavy smokers, there is theoretical support for using a combination of a sustained release product (to provide continuous background nicotine) plus a more rapidly acting product in anticipation of, or at times of, craving.

In some smokers with relative contraindications to treatment (such as acute cardiovascular disease or pregnancy) it may be prudent to use low doses of relatively short acting preparations, though in practice nicotine replacement rarely causes problems. Light smokers (< 10 cigarettes a day) and those who wait longer than an hour before their first cigarette of the day may also be best advised to choose a short acting product and to use it in advance of their regular cigarettes or at times of craving.

Table 3.

Prescribing points with nicotine replacement therapy

| Adverse effects | Cautions |

| • Nausea | • Hyperthyroidism |

| • Headache | • Diabetes |

| • Unpleasant taste | • Renal and hepatic impairment |

| • Hiccoughs and indigestion | • Gastritis and peptic ulcer disease |

| • Peripheral vascular disease | |

| • Sore throat | • Skin disorders (patches) |

| • Nose bleeds | • Avoid nasal spray when driving or operating machinery (sneezing, watering eyes) |

| • Palpitations | |

| • Dizziness | • Severe cardiovascular disease (arrhythmias, after myocardial infarction) |

| • Insomnia | |

| • Nasal irritation (with spray) | • Recent stroke |

| • Pregnancy | |

| • Breast feeding |

Note that, even with many of the cautions above, nicotine replacement therapy is still preferable to continued smoking

Nicotine replacement therapy is recommended for up to three months, followed by a gradual withdrawal. The products are generally well tolerated.

Table 4.

Contraindications to prescribing bupropion

| • History of seizures |

| • Use of drugs that lower the seizure threshold |

| • Symptoms of alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal |

| • Eating disorders |

| • Bipolar illness |

| • Central nervous system tumours |

| • Pregnancy |

| • Breast feeding |

| • Severe hepatic cirrhosis |

Bupropion

Bupropion is of similar efficacy as nicotine replacement in improving quit rates. It is an antidepressant, but its effect on smoking cessation seems to be independent of this property. Like nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion also helps to prevent weight gain. Its main adverse effect is its association with convulsions, and it is therefore contraindicated in patients with a history of epilepsy or seizures. Bupropion should not generally be prescribed for people with other risk factors for seizures, and some drugs—such as antidepressants, antimalarials, antipsychotics, quinolones, and theophylline—can lower the seizure threshold.

Table 5.

The five A's of smoking cessation

| These should form a routine component of all health service delivery |

| • Ask about tobacco use |

| • Advise quitting smoking |

| • Assess willingness to make an attempt |

| • Assist in quit attempt |

| • Arrange follow up |

Unlike nicotine replacement therapy, which is usually started at the time of quitting smoking, bupropion should be started one or two weeks before the quit date. The initial dose should be 150 mg daily for six days, increasing thereafter to 150 mg twice daily. Stop treatment if the patient has not quit smoking within eight weeks. There is no clear evidence that combining bupropion with nicotine replacement further improves quit rates, and it can lead to hypertension and insomnia.

Other drug treatments

The antidepressant nortriptyline seems to be as effective as nicotine replacement and bupropion as a smoking cessation therapy. Other new treatments are in an advanced stage of clinical trials and may become available in the near future, one of which, varenicline, is a nicotine receptor blocker and partial agonist. There is no evidence that complementary therapies such as hypnosis or acupuncture are effective.

Implementing smoking cessation in routine care

One of the major barriers to smoking cessation practice is that many health professionals do not have the skills and knowledge to intervene, or fail to intervene routinely in clinical practice. It is essential that ascertaining smoking status, delivering brief advice, and offering further help to smokers interested in quitting becomes routine practice throughout all medical disciplines, and especially with patients with COPD.

Stopping smoking is the only effective long term intervention in the management of COPD, but too many patients are still not offered the treatments that could help them quit. All smokers should receive smoking cessation intervention, however brief, at all contacts with their doctor and other health professionals. It is also important to advise patients unable to completely quit, that a reduction in the number of cigarettes smoked may still produce some benefit.

The ABC of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is edited by Graeme P Currie. The series will be published as a book by Blackwell Publishing in autumn 2006.

Competing interests: GPC has received funding for attending international conferences and honoraria for giving talks from pharmaceutical companies GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca. JB has received an honorarium and travel expenses for speaking at a conference from a manufacturer of nicotine replacement products, has been involved in clinical trials of such products, and has been a paid consultant for companies developing such products.

The portrait of King James I is reproduced with permission of Roy Miles Fine Paintings/BAL. The graph showing the effect of stopping smoking on lung function is adapted from Hogg JC. Lancet 2004;364: 709-21.

References

- • Silagy C, Lancaster T, Stead L, Mant D, Fowler G. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3): CD000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Hughes JR, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(4): CD000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Roddy E. Bupropion and other non-nicotine pharmacotherapies. BMJ 2004;328: 509-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Jamrozik K. Population strategies to prevent smoking. BMJ 2004; 328: 759-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Molyneux A. Nicotine replacement therapy. BMJ 2004;328: 454-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • West R, McNeill A, Raw M. Smoking cessation guidelines for health professionals: an update. Health Education Authority. Thorax 2000; 55: 987-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]