Abstract

Goodpasture's syndrome is an autoimmune disease characterized by pulmonary hemorrhage, glomerulonephritis, and antiglomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibodies. We have studied a rat model with chimeric proteins (CPs) consisting of portions of the nephritogenic non-collagenous domain of α3 type IV collagen (α3(IV)NC1) and non-nephritogenic α1(IV)NC1. CPs with aminoterminal α3 that contains the major epitope for Goodpasture antibody binding induced EAG. We next immunized with D3, an α1(IV)NC1 CP with 69AA of α3(IV)NC1 (binds Goodpasture sera), D4, the D3 construct shortened by 4 AA (nonbinding), P9 and P10, single AA mutants (nonbinding) and S2, an α1(IV)NC1 with nine AA of α3(IV)NC1 (binding). GBM, S2 and D3 induced EAG. GBM immunized rats had intense IgG deposits but S2 and D3 rats had minimal deposits. A 13 mer rat peptide encompassing the aminoterminal site induced EAG sans antibody, while peptides not encompassing the region failed to induce GN. Asparagine at position 19 rather than isoleucine was essential for disease induction.

These studies define critical limited AA sequences of α3(IV)NC1 associated with glomerulonephritis without antibody, and demonstrate that this region contains a T-cell epitope responsible for induction of glomerulonephritis.

Introduction

In 1919, Ernest Goodpasture described a clinical syndrome of pulmonary hemorrhage associated with influenza infection and acute glomerulonephritis (1). In 1958 Stanton and Tange reiterated this finding in patients with pulmonary renal disorders and described it as “Goodpasture's syndrome” based on the earlier report from 1919 (2). It is now understood that there are multiple causes of the association between glomerulonephritis and pulmonary hemorrhage including vasculitis, immune complex disease, congestive heart failure, multiple infectious etiologies and a host of others (3,4). We now reserve the term Goodpasture's syndrome for those individuals who have pulmonary hemorrhage associated with glomerulonephritis with the presence of antibodies to basement membranes bound within the kidney and frequently within the lung. Most of these patients also have circulating antiglomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibodies. Fixation of the patient's own antibodies to their own GBM was the first indication of both an autoimmune process and localization of the responsible antigen to kidney basement membrane. There are patients who have circulating and bound antibodies but have only glomerulonephritis, others with only pulmonary hemorrhage, and yet others with circulating and bound antibody with no clinical disease. Serologic evidence to incriminate the type IV collagen component of GBM as the predominant target was provided by numerous investigators using Goodpasture's sera (5,6,7). This collagen is made up of a trimer of α1 and α2 collagen consisting of a 7S straight portion, a triple helix, and a noncollagenous domain (NC1) which contains the reactive epitope mapped with Goodpasture's sera (5,8). GBM, lung, choroid plexus and lens basement membrane contain other unique chains (9). With the advent of monoclonal antibodies, molecular biologic techniques and appropriate animal models, much has been learned about the pathogenesis of Goodpasture's syndrome. Perhaps there is more information on this disease than any other autoimmune human glomerulonephritis. For decades the disease has been considered to be mediated by antibodies (10,11) alone with a few voices crying from the wilderness that cell mediated immunity was also involved or even primal in some circumstances (12–15).

It has been relatively straight forward to show that antibodies can induce experimental glomerulonephritis. It has been much more challenging to document a role for cellular immunity. Some of the earliest evidence for induction of experimental glomerulonephritis via the cell mediated immune system derives from studies in chickens in which bursectomy rendered animals with intact T cell immunity unable to mount an antibody response (16). Immunization with crude GBM resulted in glomerulonephritis in the absence of immunoglobulin, and the glomerulonephritis could be passively transferred by cells (14). This was followed by development of a model in rats induced by digests of GBM, associated with pulmonary hemorrhage, glomerulonephritis, progressive proteinuria and renal failure similar both clinically and histologically to human disease (17,18). Immunization with GBM was associated with linear IgG deposits on the GBM, intense fibrin deposition, and crescents progressing to glomerular sclerosis and loss of kidney function. Ultrastructurally there were monocytes, multinucleated giant cells and lymphocytes within glomeruli, confirmed phenotypically with monoclonal antibodies (18). Immunization of rats with collagenase solubilized GBM, column chromatograph purified α3(IV)NC1, and recombinant α3(IV)NC1 domain have all shown this to be the responsible antigen to induce glomerulonephritis in susceptible rats (17–20). Collagen containing the standard α1 and α2NC1 domains, absent α3, is not nephritogenic (20,21). Thus, the α3 NC1 domain, a 232 amino acid length protein of type IV collagen, contains the disease causing epitopes identified by Goodpasture serum antibody binding and T cell proliferation from patients with Goodpasture's syndrome. Therapeutic intervention in this severe disease would be greatly augmented by a thorough understanding of the actual disease-producing epitopes and pathogenetic processes. We and others have focused on further defining the responsible epitopes with a goal of eventual specific therapeutic intervention.

Materials and Methods

We have used recombinant proteins of α1 and α3(IV)NC1, chimeric constructs of α3 and α1(IV)NC1, mutations within these various constructs, and synthetic peptides to examine pathogenesis further (8,22,23). We followed animal antibody response, proteinuria and hematuria, clinical kidney function, and histologic changes of the disease (18). Purified proteins were derived from column chromatography. ELISA assays, immunoblots, and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis were by standard techniques (24,25). Constructs were made by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methodology with site directed mutagenesis using an overlap extension PCR reaction (8,22). Constructs were expressed in HEK293 cells and purified by their 6 his tags.

Results

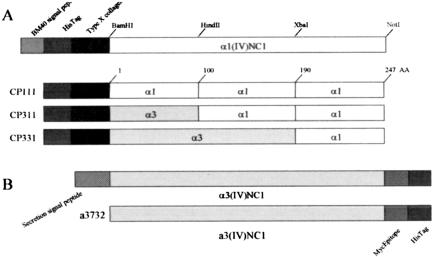

Molecular mapping using chimeric proteins consisting of different portions of nephritogenic α3NC1 domain with nonnephritogenic α1NC1 domain have delineated two immunodominant antibody binding domains in α3(IV)NC1, the first in the middle portion of the molecule and the second in the amino terminal third (8,26–28). These two portions contain sequences necessary for a conformational structure which binds Goodpasture's sera and a monoclonal antibody which recognizes α3(IV)NC1, Mab 17 (27,28). These two portions make up the majority of antibody binding sites for Goodpasture's sera although there are others. Clinically the strongest correlation in man with antibody binding and disease is with the aminoterminal portion. To determine if the epitopes defined with Goodpasture's sera were concordant with glomerulonephritis induction in our model, WKY rats were immunized with chimeric proteins or full-length recombinant α3(IV)NC1 domain (Figure 1). Constructs consisted of thirds of α3(IV)NC1 domain replaced with corresponding sequences of homologous nonreactive α1(IV)NC1 domain. Constructs containing all three domains of α3 are designated chimeric protein (CP333). Those with all α1 would be CP111, constructs containing an amino terminus would be CP311. Two other constructs EA and EB consisting entirely of α1(IV)NC1 except for the two immunodominant amino acids from the first and second thirds of α3(IV)NC1 were also used to immunize rats (27,28). CP311 immunized rats as well as full recombinant immunized rats had typical glomerulonephritis within a few weeks with CP311 inducing the more severe disease, comparable to positive controls. EA from the amino terminal region induced glomerulonephritis but EB from the middle region did not. Disease in recombinant protein immunized rats was indistinguishable from native GBM immunized rats.

Fig. 1.

Cartoon depicting construction of chimeric proteins consisting of thirds of α3(IV)NC1 domain and homologous α1(IV)NC1 domain. After data from Chen, L, et al, Kidney Int 64:2108–2120, 2003.

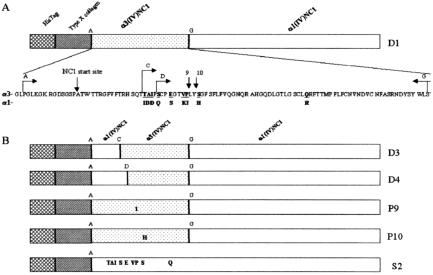

Selected areas within the aminoterminus, which might disrupt antibody binding, were then targeted for point mutations within the α3 portion of the chimeric protein (8) (Figure 2). A series of constructs were shown to either maintain Goodpasture's serum antibody binding or abrogate it. For these studies rats were immunized with collagenase solubilized GBM (csGBM), which binds Goodpasture's sera, D3 which is an α1(IV)NC1 chimeric protein with 69 aminoterminal amino acids of α3(IV)NC1 which also binds Goodpasture's sera, D4, the D3 construct shortened by four amino-terminal amino acids which is nonbinding, P9 and P10, single amino acid mutants which are nonbinding, and S2, and α1(IV)NC1 domain with nine amino acids of α3(IV)NC1 domain which binds Goodpasture's sera. All rats immunized with csGBM as well as those immunized with S2, and half of D3 immunized rats developed glomerulonephritis. Positive control rats immunized with csGBM had intense GBM bound IgG deposits, but S2 and D3 rats had minimal deposits. None of D4, P9 or P10 rats developed glomerulonephritis. Lymphocytes from positive control nephritic rats proliferated with csGBM, S2 and D3 but not with D4, P9 or P10.

Fig. 2.

Cartoon of constructs and mutations used to explore aminoterminal nephritogenic epitopes. After data from Hellmark, T, et al, J Biol Chem 278:46, 516–46, 522, 2003.

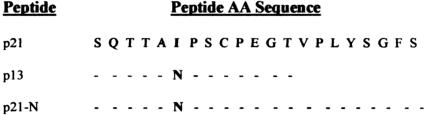

These studies showed that discrete segments of α3(IV)NC1 within the α1(IV)NC1 backbone can induce glomerulonephritis and that single amino acid mutations within the epitope render the antigen unresponsive to Goodpasture's sera and incapable of inducing glomerulonephritis. They also define a critical amino acid sequence within α3(IV)NC1 of nine or less amino acid which confers the ability to induce glomerulonephritis to the non-nephritogenic α1(IV)NC1 but without antibody binding. We postulated that this latter region could be a T-cell epitope responsible for inducing glomerulonephritis in rats and possibly associated with Goodpasture's syndrome in man. We therefore constructed peptides spanning this nine amino acid region based upon the human sequence for α3(IV)NC1 domain (Figure 3). Surprisingly, none of 50 rats immunized under various conditions with a 21 mer peptide developed disease. We next changed the amino acid in position 19 from isoleucine to asparagine, the rat sequence, and shortened the sequence to 13 amino acids. 21 of 26 rats developed severe glomerulonephritis with crescents, proteinuria and hematuria with decreased kidney function (29). There was no antibody bound on the GBM in two thirds of animals nor any circulating anti-GBM antibody. There was no correlation between severity of histologic damage and antibody deposits. Eluates from the nephritic kidneys and serum of antibody negative rats fixed equally to immunizing peptide and did not bind to recombinant α3(IV)NC1 domain. Rat lymphocytes underwent proliferation in response to the peptides. Peptides not encompassing the region but involving all of the rest of α3NC1 domain failed to induce glomerulonephritis. Substitution of asparagine at position 19 in the original 21 amino acid sequence converted it to a nephritogenic peptide.

Fig. 3.

Sequence of the peptides used to immunize rats.

Discussion

These findings demonstrate that discrete segments of α3(IV)NC1 can induce glomerulonephritis and that single amino acid mutations can render the epitope unresponsive to both antibody binding and induction of glomerulonephritis. They define a critical limited amino acid sequence within this region associated with glomerulonephritis without antibody and show that this region contains a T-cell epitope responsible for induction of glomerulonephritis without antibody in this model of rats and possibly in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by USPHS Grant DK 55801 from the NIDDK, K2001-71X-09487-11C from the Swedish Research Council, the Tegger Foundation and the Swedish Society for Medical Research (SSMF). We thank the Biomolecular Research Facility at University of Virginia for their expert support on protein sequencing, and Dr. Peter Lobo for collaboration with the cell proliferation assays. We are grateful to Ms. Chun Gao for her excellent technical assistance. We thank Joyce De Guzman for secretarial assistance and Lena Gunnarsson for technical assistance.

DISCUSSION

Wolf, Boston: What happens in the lungs?

Bolton, Charlottesville: These animals have mild pulmonary hemorrhage and petechiae in the lungs, but don't develop the full blown syndrome that we see in humans. This is probably because in almost in all cases of human pulmonary hemorrhage associated with antibodies, there's a predisposing insult to the lungs. So it occurs with high association with smoking, or possibly petroleum fume exposure, etc. If you put gasoline down the trachea of rabbits or injure the endothelium in the lung with oxygen, then you can induce a full blown pulmonary syndrome.

Schreiner, Los Altos: Kline, Goodpastures is often preceded by a vaguely defined event that seems to resemble an infection. It implies that some trauma then generates this epitope. If you present the S2 sequence of collagen, or if you present collagen, to human macrophages, do you observe generation of this epitope that you have tracked via the rat studies? Would spontaneous generation of the epitope induced by feeding this protein to macrophages suggest that, in fact, this epitope might be selected out as an antigen to be presented to T cells?

Bolton: We have not, but this has been one of the considerations. We were very surprised when we used the whole protein and got disease, yet the peptide did not cause disease. So we think that intracellular processing or some sort of modification of the protein must be occurring in order for the peptide to cause disease in the setting of the whole protein, but not in the form of the isolated peptide. But we've not done the macrophage studies.

Luke, Cincinnati: How does this fit with the Alport syndrome story? How does your epitope fit in there?

Bolton: As you know Alport's is a hereditary disease, which was not mentioned this morning, but to us Nephrologists it's a near and dear hereditary disease. It is associated with abnormalities in the alpha-5 collagen chain that causes disassembly of the network of alpha 3, 4, 5, in the basement membrane associated with histologic abnormalities and with glomerulonephritis that is progressive. When you transplant a normal kidney into a patient who has Alport's syndrome as the cause of end-stage renal disease, some of those patients develop antibodies to the new antigen in the Alport's recipient with loss of the graft. I would point out that a lot of those patients actually develop antibodies, some of which fix to the basement membrane, but some of which do not cause loss of the graft. So it's a much more complicated story than simply exposure to the cryptic antigen. But this example of nature illustrates that this neo-antigen results in autoimmunization.

Mahaffey, Washington: In studies of environmental exposures to chemicals, particularly to airborne chemicals, we are constantly asked questions about genetically susceptible subpopulations. Would you comment on this with respect to what you have just presented?

Bolton: There's a large literature about the association between Goodpastures syndrome and exposure to various chemicals, especially petroleum related chemicals, as occurs with gas station operators, and it's thought that could play a role. Almost every year, there's new paper coming out saying yea or nea, that it does or does not cause disease. There is, however, genetic susceptibility related to MHC type, which not only seems to predispose the individual to disease, but also influences the severity of disease. HLA B7 with DR2 for instance is associated with much worse disease.

Mahaffey: In terms of percent of population for genetic susceptible for airborne contaminants, any estimate as to the percent of people, not necessarily with just this syndrome, but broadly that might be the genetically susceptible portion?

Bolton: I don't think we know enough to assess what the base risk factors are. We know that it's an unusual disease. One in a million or so patients gets the disease. We know from MHC mapping that there are many more individuals “a risk,” but they don't get disease. Only a very small percentage of them actually develop disease. We think it's related to exposure of the cryptic antigen. It occurs after infections as George was saying, which can disrupt the basement membrane, it occurs after membranous nephropathy which damages the basement membrane, and after acute tubular necrosis and cortical necrosis, all of which cause damage to the basement membrane and presumably expose the cryptic antigen.

Mahaffey: If you were to focus on not just this syndrome but on a broad array of syndromes, and not just the full clinical picture but to those who are susceptible to say airborne chemical contaminants—could you guess this to a percent?

Bolton: I have no idea.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goodpasture EW. The significance of certain pulmonary lesions in relation to the etiology of influenza. Am J Med Sci. 1919;158:863–870. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31818fff94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanton MC, Tange JD. Goodpasture's syndrome (pulmonary haemorrhage associated with glomerulonephritis) Aust Ann Med. 1958;7:132–144. doi: 10.1111/imj.1958.7.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolton WK. Goodpasture's syndrome. Nephrology Forum. Kidney Int. 1996;50:1753–1766. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rees AJ, Lockwood CM. Antiglomerular basement membrane antibody-mediated nephritis. In: Schrier RW, Gottschalk CW, editors. Diseases of the Kidney, chap 68. Boston: 1988. pp. 2091–2126. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudson BG, Weislander J, Wisdom BJ, Noelken ME. Goodpasture syndrome: Molecular architecture and function of basement membrane antigen. Lab Invest. 1989;61:256–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wieslander J, Bygren P, Heinegård D. Isolation of the specific glomerular basement membrane antigen involved in Goodpasture syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1984;81:1544–1548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalluri R, Sun MJ, Hudson BG, Neilson EG. The Goodpasture autoantigen: Structural delineation of two immunologically privileged epitopes on α3(IV) chain of type IV collagen. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9062–9068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.9062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hellmark T, Burkhardt H, Wieslander J. Goodpasture Disease: Characterization of a single conformational epitope as the target of pathogenic autoantibodies. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25862–25868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudson BG, Tryggvason K, Sundaramoorthy M, Neilson EG. Alport's syndrome, Goodpasture's syndrome, and type IV collagen. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2543–2556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lerner RA, Glassock RJ, Dixon FJ. The role of anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody in the pathogenesis of human glomerulonephritis. J Exp Med. 1967;126:989–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.126.6.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon FJ. What are sensitized cells doing in glomerulonephritis? N Engl J Med. 1970;283:536–537. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197009032831011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolton WK, Innes DJ, Sturgill BC, Kaiser DL. T-cells and macrophages in rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis: Clinicopathologic correlations. Kidney Int. 1987;32:869–876. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolton WK. What sensitized cells just might be doing in glomerulonephritis. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:713–714. doi: 10.1172/JCI15285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolton WK, Chandra M, Tyson TM, Kirkpatrick PR, Sadovnic J, Sturgill BC. Transfer of experimental glomerulonephritis in chickens by mononuclear cells. Kidney Int. 1988;34:598–610. doi: 10.1038/ki.1988.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolton WK. Mechanisms of glomerular injury: Injury mediated by sensitized lymphocytes. Semin Nephrol. 1991;11:285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolton WK, Tucker FL, Sturgill BC. New avian model of experimental glomerulonephritis consistent with mediation by cellular immunity. J Clin Invest. 1984;73:1263–1276. doi: 10.1172/JCI111328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sado Y, Okigaki T, Takamiya H, Seno S. Experimental autoimmune glomerulonephritis with pulmonary hemorrhage in rats. The dose-effect relationship of the nephritogenic antigen from bovine glomerular basement membrane. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1984;15:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolton WK, May WJ, Sturgill BC. Proliferative glomerulonephritis in rats: A model for autoimmune glomerulonephritis in humans. Kidney Int. 1993;44:294–306. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalluri R, Gattone VH, II, Noelken ME, Hudson BG. The α3 chain of type IV collagen induces autoimmune Goodpasture syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:6201–6205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sado Y, Boutaud AA, Kagawa M, Naito I, Ninomiya Y, Hudson BG. Induction of anti-GBM nephritis in rats by recombinant α3(IV) NC1 and α4(IV) NC1 of type IV collagen. Kidney Int. 1998;53:664–671. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolton WK, May WJ, Sturgill BC, Luo A-M, Fox PL. Study of EHS type IV collagen lacking Goodpasture's epitope in glomerulonephritis in rats. Kidney Int. 1995;47:404–410. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hellmark T, Johansson C, Wieslander J. Characterization of anti-GBM antibodies involved in Goodpasture's syndrome. Kidney Int. 1994;46:823–829. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo A-M, Fox J, Chen L, Bolton WK. Synthetic peptides of Goodpasture's antigen in antiglomerular basement membrane nephritis in rats. J Lab Clin Med. 2002;139:303–310. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2002.123623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, Hellmark T, Wieslander J, Bolton WK. Immunodominant epitopes of α3(IV)NC1 induce autoimmune glomerulonephritis in rats. Kidney Int. 2003;64:2108–2120. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hellmark T, Chen L, Ohlsson S, Wieslander J, Bolton WK. Point mutations of single amino acids abolish ability of α3 NC1 domain to elicit experimental autoimmune glomerulonephritis in rats. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46516–46522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hellmark T, Segelmark M, Unger C, Burkhardt H, Saus J, Wieslander J. Identification of a clinically relevant immunodominant region of collagen IV in Goodpasture disease. Kidney Int. 1999;55:936–944. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.055003936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borza DB, Netzer KO, Leinonen A, Todd P, Cervera J, Saus J, Hudson BG. The Goodpasture autoantigen: identification of multiple cryptic epitopes on the NC1 domain of the α3 (IV) collagen chain. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6030–6037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.6030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Netzer KO, Leinonen A, Boutaud AA, Borza DB, Todd P, Gunwar S, Langeveld JPM, Hudson BG. The Goodpasture antigen: Mapping the major conformational epitope(s) of α3(IV) collagen to residues 17–31 and 127–141 of the NC1 domain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11267–11274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolton WK, Chen L, Hellmark T, Wieslander J, Fox J. Production of no immune deposit (Pauci immune) experimental autoimmune glomerulonephritis (EAG) with a peptide of Goodpasture (GP) antigen. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:167A. [Google Scholar]