Abstract

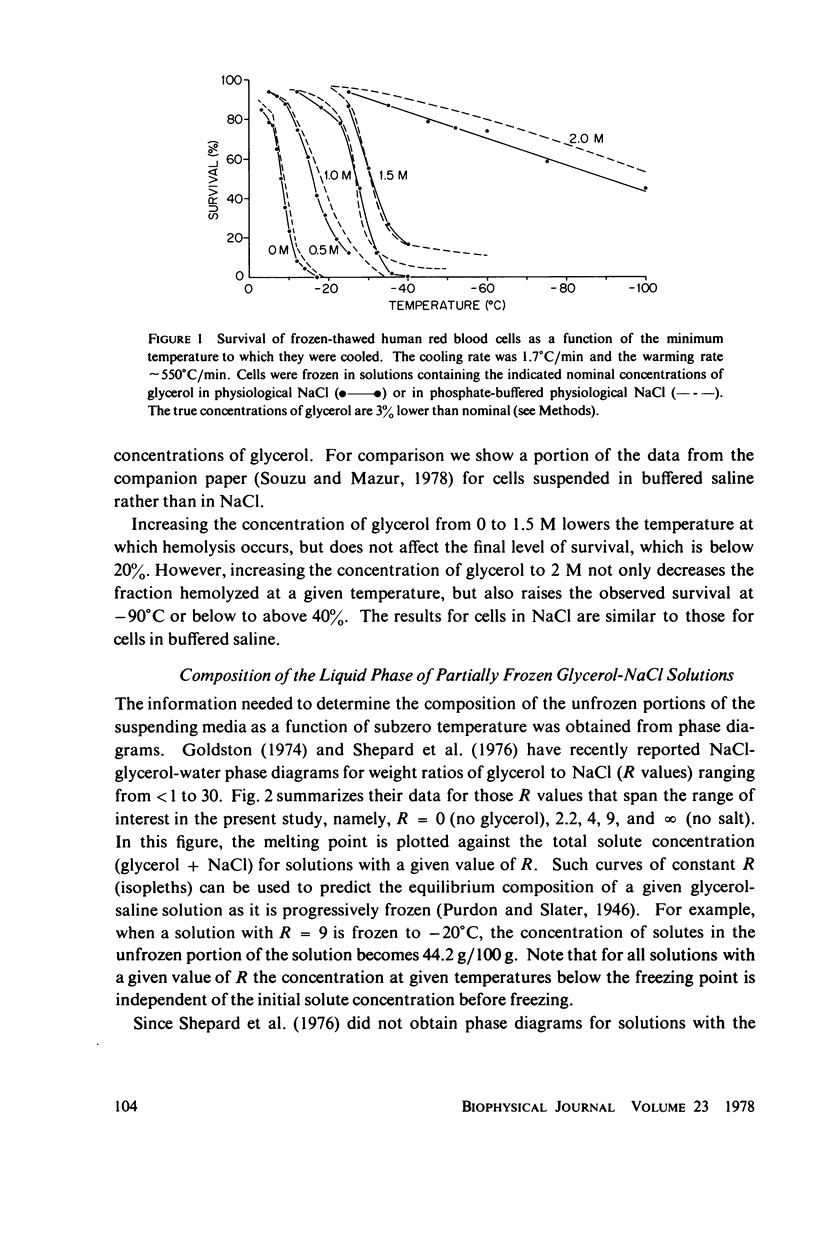

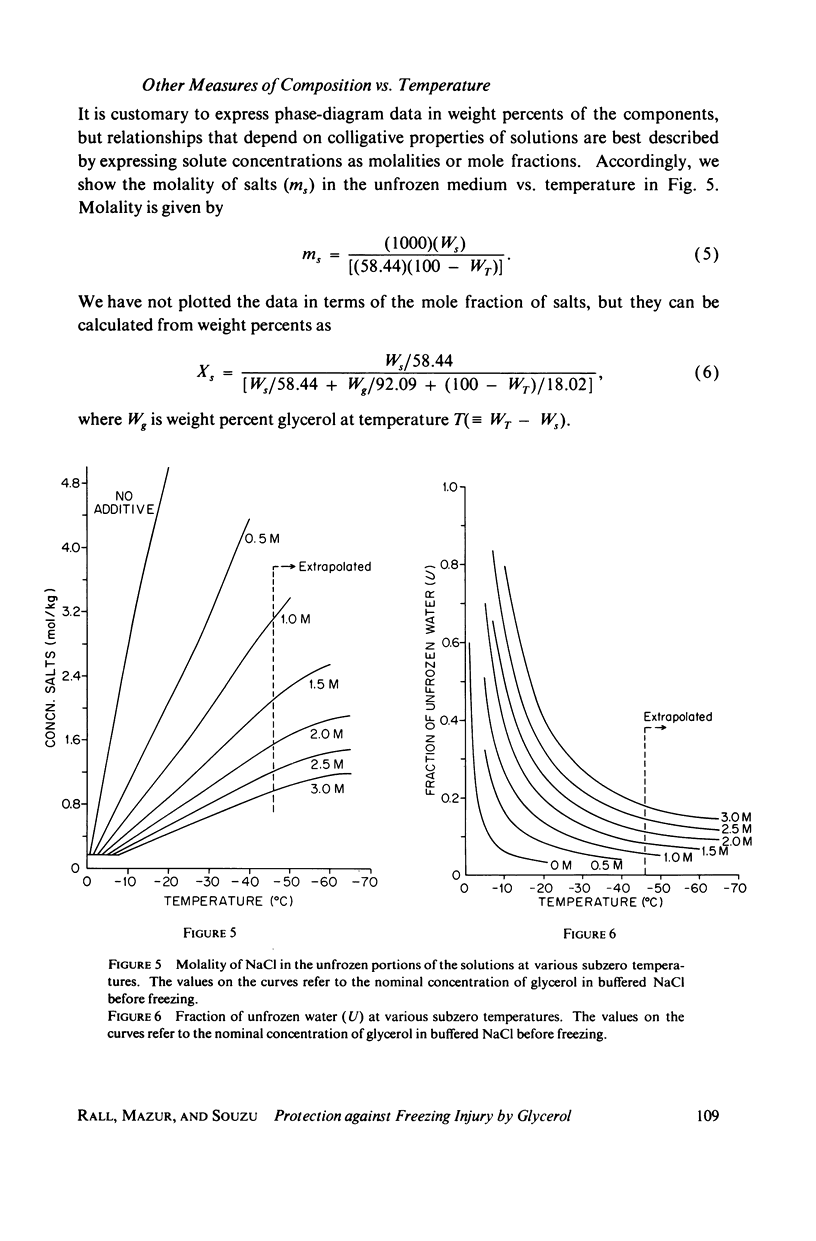

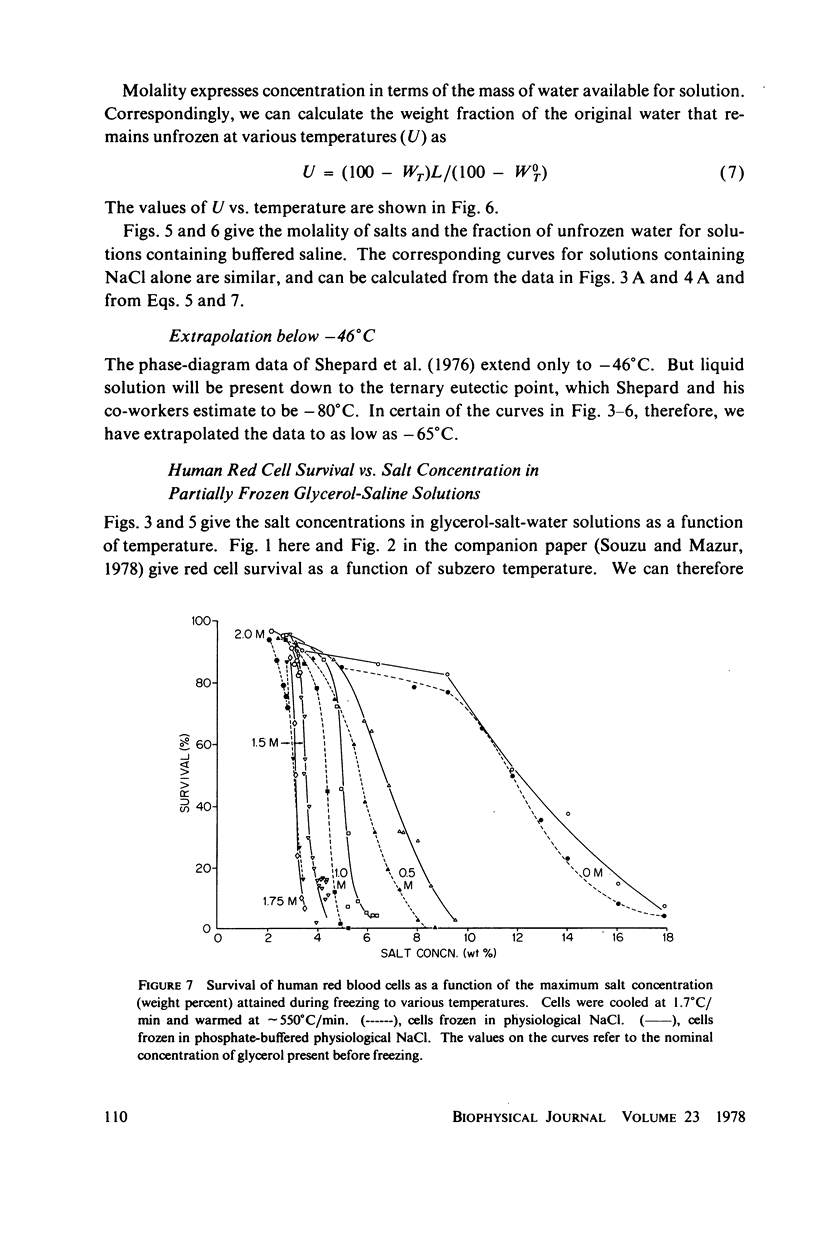

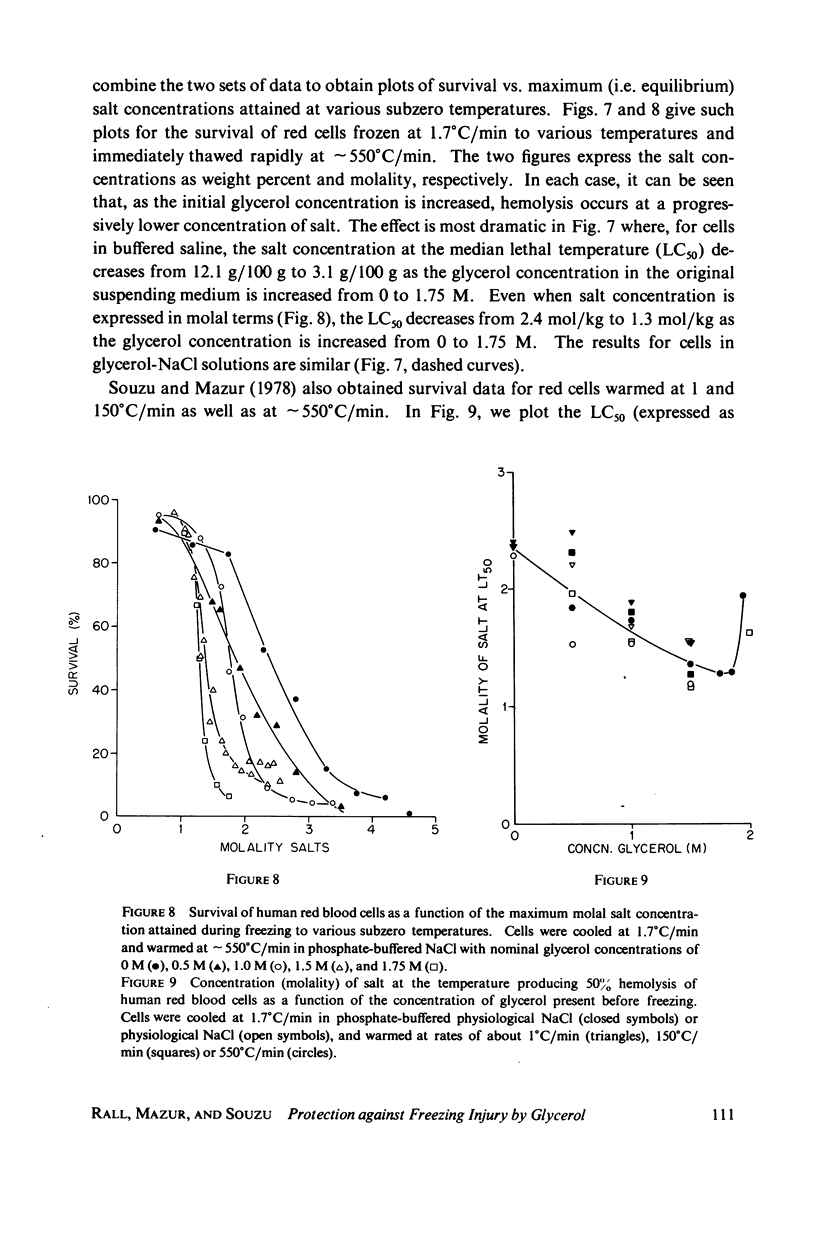

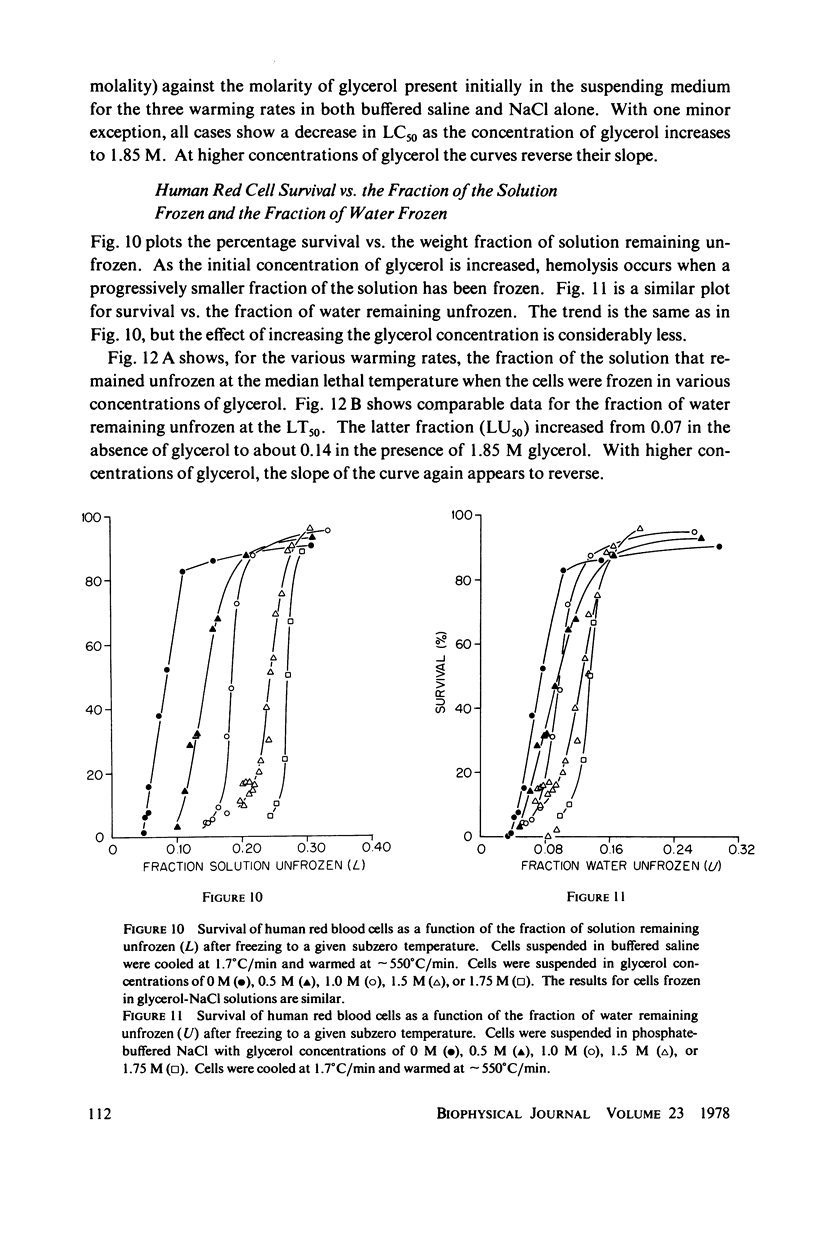

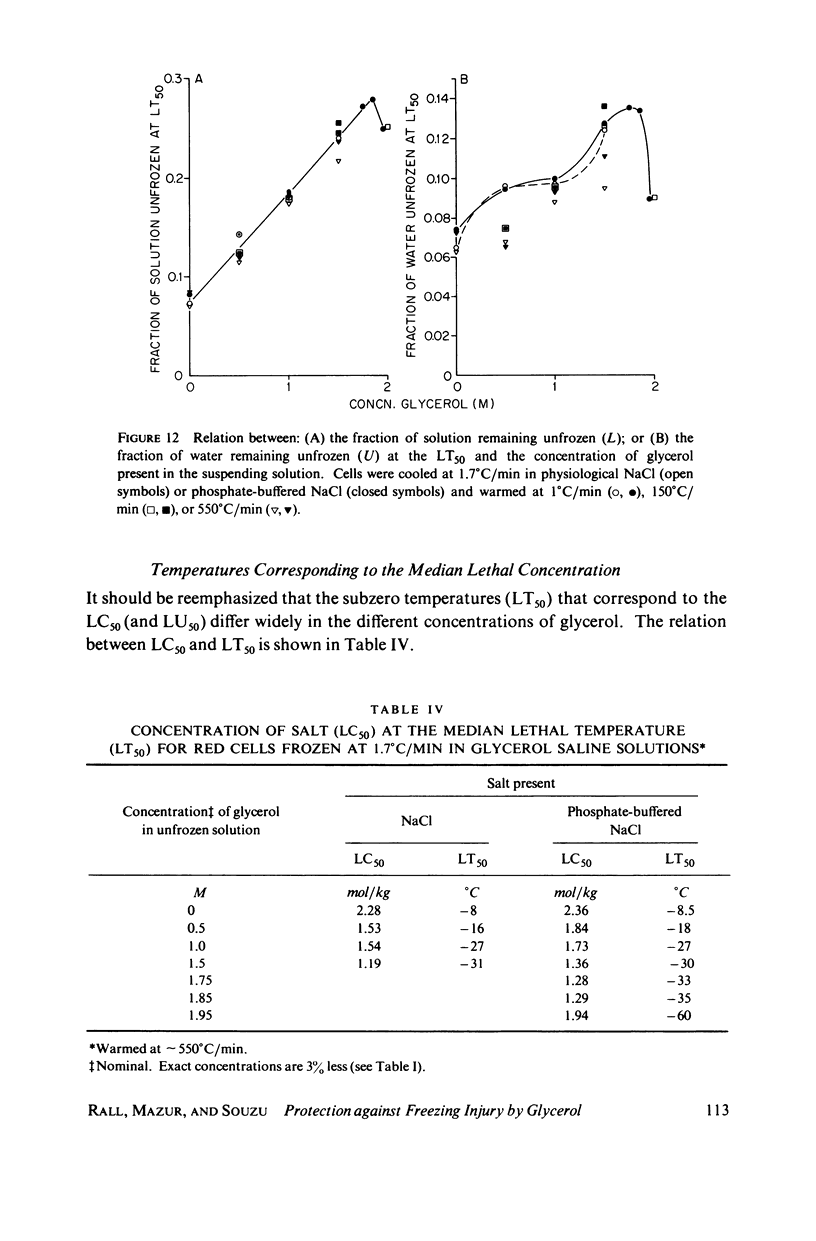

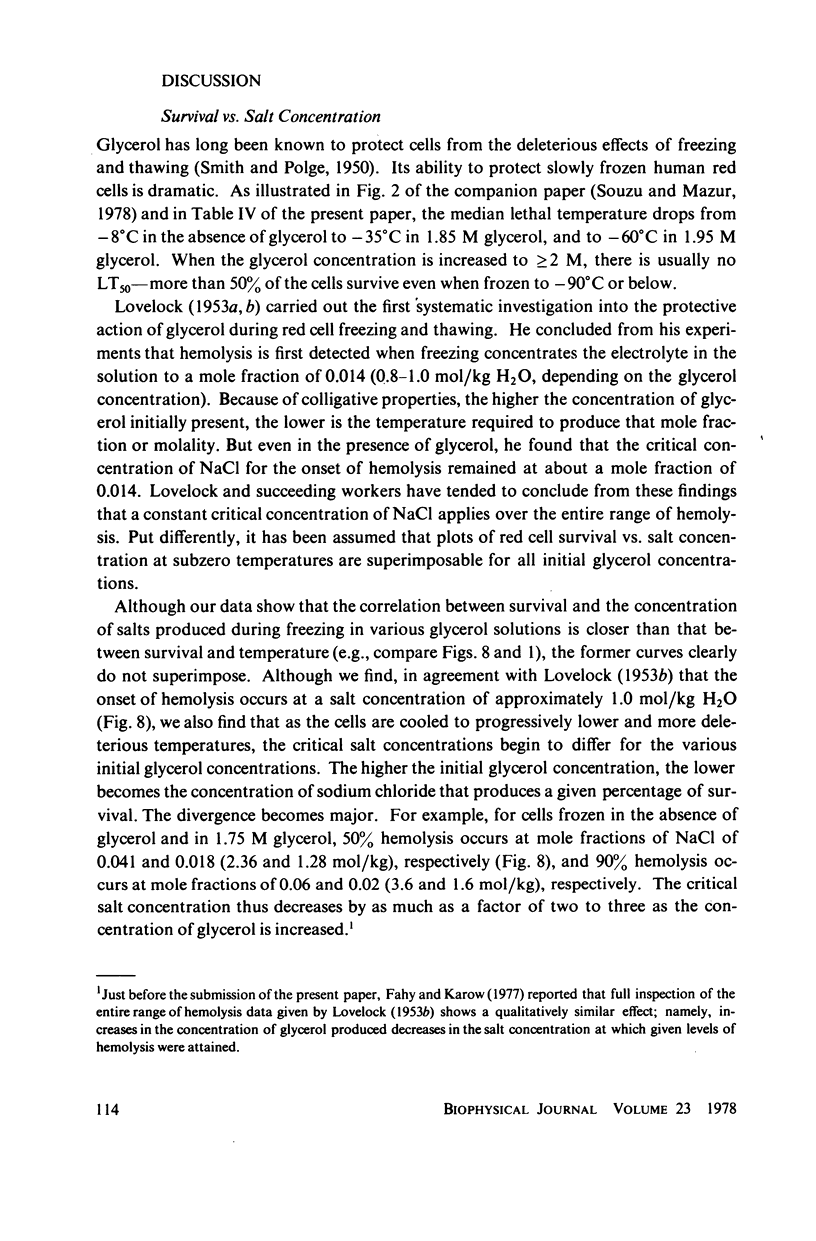

One theory of freezing damage suggests that slowly cooled cells are killed by being exposed to increasing concentrations of electrolytes as the suspending medium freezes. A corollary to this view is that protective additives such as glycerol protect cells by acting colligatively to reduce the electrolyte concentration at any subzero temperature. Recently published phase-diagram data for the ternary system glycerol-NaCl-water by M. L. Shepard et al. (Cryobiology, 13:9-23, 1976), in combination with the data on human red cell survival vs. subzero temperature presented here and in the companion study of Souzu and Mazur (Biophys. J., 23:89-100), permit a precise test of this theory. Appropriate liquidus phase-diagram information for the solutions used in the red cell freezing experiments was obtained by interpolation of the liquidus data of Shepard and his co-workers. The results of phase-diagram analysis of red cell survival indicate that the correlation between the temperature that yields 50% hemolysis (LT50) and the electrolyte concentration attained at that temperature in various concentrations of glycerol is poor. With increasing concentrations of glycerol, the cells were killed at progressively lower concentrations of NaCl. For example, the LT50 for cells frozen in the absence of glycerol corresponds to a NaCl concentration of 12 weight percent (2.4 molal), while for cells frozen in 1.75 M glycerol in buffered saline the LT50 corresponds to 3.0 weight percent NaCl (1.3 molal). The data, in combination with other findings, lead to two conclusions: (a) The protection from glycerol is due to its colligative ability to reduce the concentration of sodium chloride in the external medium, but (b) the protection is less than that expected from colligative effects; apparently glycerol itself can also be a source of damage, probably because it renders the red cells susceptible to osmotic shock during thawing.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Cocks F. H., Brower W. E. Phase diagram relationships in cryobiology. Cryobiology. 1974 Aug;11(4):340–358. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(74)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J. S. Nonsolvent water in human erythrocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1967 May;50(5):1311–1325. doi: 10.1085/jgp.50.5.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy G. M., Karow A. M., Jr Ultrastructure-function correlative studies for cardiac cryopreservation. V. Absence of a correlation between electrolyte toxicity and cryoinjury in the slowly frozen, cryoprotected rat heart. Cryobiology. 1977 Aug;14(4):418–427. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(77)90003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOVELOCK J. E. The haemolysis of human red blood-cells by freezing and thawing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1953 Mar;10(3):414–426. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(53)90273-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOVELOCK J. E. The mechanism of the protective action of glycerol against haemolysis by freezing and thawing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1953 May;11(1):28–36. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(53)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUSENA C. V. Ice propagation in glycerol solutions at temperatures below--40 degrees C. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1960 Apr 13;85:541–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb49981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUSENA C. V. Ice propagation in systems of biological interest. III. Effect of solutes on nucleation and growth of ice crystals. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1955 Aug;57(2):277–284. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(55)90289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibo S. P. Freezing damage of bovine erythrocytes: simulation using glycerol concentration changes at subzero temperatures. Cryobiology. 1976 Dec;13(6):587–598. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(76)90001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAZUR P. KINETICS OF WATER LOSS FROM CELLS AT SUBZERO TEMPERATURES AND THE LIKELIHOOD OF INTRACELLULAR FREEZING. J Gen Physiol. 1963 Nov;47:347–369. doi: 10.1085/jgp.47.2.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P. Cryobiology: the freezing of biological systems. Science. 1970 May 22;168(3934):939–949. doi: 10.1126/science.168.3934.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P., Leibo S. P., Miller R. H. Permeability of the bovine red cell to glycerol in hyperosmotic solutions at various temperatures. J Membr Biol. 1974;15(2):107–136. doi: 10.1007/BF01870084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P., Miller R. H., Leibo S. P. Survival of frozen-thawed bovine red cells as a function of the permeation of glycerol and sucrose. J Membr Biol. 1974;15(2):137–158. doi: 10.1007/BF01870085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P., Miller R. H. Permeability of the human erythrocyte to glycerol in 1 and 2 M solutions at 0 or 20 degrees C. Cryobiology. 1976 Oct;13(5):507–522. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(76)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur P., Miller R. H. Survival of frozen-thawed human red cells as a function of the permeation of glycerol and sucrose. Cryobiology. 1976 Oct;13(5):523–536. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(76)90145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meryman H. T. Freezing injury and its prevention in living cells. Annu Rev Biophys Bioeng. 1974;3(0):341–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.03.060174.002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meryman H. T., Williams R. J., Douglas M. S. Freezing injury from "solution effects" and its prevention by natural or artificial cryoprotection. Cryobiology. 1977 Jun;14(3):287–302. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(77)90177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. H., Mazur P. Survival of frozen-thawed human red cells as a function of cooling and warming velocities. Cryobiology. 1976 Aug;13(4):404–414. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(76)90096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mironescu S. Hyperosmotic injury in mammalian cells. Survival of CHO cells in unprotected and DMSO-treated cultures. Cryobiology. 1977 Aug;14(4):451–465. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(77)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris G. J., Farrant J. Interactions of cooling rate and protective additive on the survival of washed human erythrocytes frozen to -196 degrees C. Cryobiology. 1972 Jun;9(3):173–181. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(72)90029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH A. U., POLGE C. Survival of spermatozoa at low temperatures. Nature. 1950 Oct 21;166(4225):668–669. doi: 10.1038/166668a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard M. L., Goldston C. S., Cocks F. H. The H2O-NaCl-glycerol phase diagram and its application in cryobiology. Cryobiology. 1976 Feb;13(1):9–23. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(76)90154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souzu H., Mazur P. Temperature dependence of the survival of human erythrocytes frozen slowly in various concentrations of glycerol. Biophys J. 1978 Jul;23(1):89–100. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(78)85435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steponkus P. L., Garber M. P., Myers S. P., Lineberger R. D. Effects of cold acclimation and freezing on structure and function of chloroplast thylakoids. Cryobiology. 1977 Jun;14(3):303–321. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(77)90178-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOOD T. H., ROSENBERG A. M. Freezing in yeast cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1957 Jul;25(1):78–87. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(57)90421-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]