Summary

CD4+CD25+ T-regulatory cells (Treg) can inhibit the proliferation and cytokine secretion of CD4+CD25− helper T cells in mice and humans. In murine tumor models, the presence of these Treg cells can inhibit the antitumor effectiveness of T-cell transfer and active immunization approaches. We have thus initiated efforts to eliminate Treg cells selectively from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) to potentially bolster antitumor responses. LMB-2 is a recombinant immunotoxin that is a fusion of a single-chain Fv fragment of the anti-Tac anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody to a truncated form of the bacterial Pseudomonas exotoxin A. In vitro incubation of human PBMCs with LMB-2 reduced the levels of CD4+CD25+ and Foxp3-expressing cells without impairing the function of the remaining lymphocytes. The short in vivo half-life of LMB-2 makes it an attractive candidate for reducing human Treg cells in vivo before the administration of cancer vaccine or cell transfer immunotherapy approaches.

Keywords: human, immunotoxin, LMB-2, CD25, regulatory T cell, depletion, Pseudomonas exotoxin

In humans, naturally occurring CD4+ CD25+ T-regulatory (Treg) cells, which represent approximately 5% of the peripheral CD4+ T-cell compartment, maintain homeostatic peripheral self-tolerance by suppressing autoreactive T cells.1 Treg cells constitutively express the α-chain of the interleukin (IL)-2 receptor (CD25), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4), glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor (GITR), and transcription factor Forkhead box P3 (Foxp3).2 Compared with CD25−CD4+ T cells, CD25+ Treg cells exhibit a hypoproliferative capacity and possess the ability to suppress CD8+ and CD25− CD4+ T-cell activation in vitro through a largely unknown mechanism. That Treg cells are key mediators of self-tolerance is evidenced in individuals genetically predisposed to the immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX), a recessive and often fatal disorder of early childhood caused by loss of function mutations of Foxp3 and the resultant lack of Treg cells.3

Peripheral blood lymphocytes from melanoma patients contain functional CD4+CD25+ Treg cells, and melanoma antigen-specific Treg cells have been described.4,5 Further, CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells in human metastatic melanoma lymph nodes have been reported to inhibit the function of infiltrating T cells.6 Treg cells are also reported to contribute to growth of human ovarian carcinomas in vivo by suppressing tumor-specific T-cell immunity and to be associated with reduced survival of patients with ovarian cancer.7 Thus, the immune inhibitory effects of Treg cells may account, in part, for the poor clinical response rates reported in cancer patients receiving immunotherapy. The impact of CD4+CD25+ Treg cells on adoptive immunotherapy has recently been evaluated in a mouse melanoma model. Adoptive transfer of tumor/self-reactive CD8+ T cells with vaccination and IL-2 led to regression of large established B16 melanoma in lymphodepleted hosts.8 In cotransfer experiments, adoptive transfer of CD25−CD4+ T helper cells with tumor/self-reactive CD8+ T cells and vaccination into CD4+ T-cell–deficient recipients resulted in regression of established tumor and concomitant autoimmunity.9 In contrast, cotransfer of CD25+ Treg cells alone or combined with CD25−CD4+ T helper cells inhibited effective immunotherapy. Based on preclinical findings suggesting that selective depletion of Treg cells and enrichment of CD4+ T helper cells may improve cancer therapy, we sought to neutralize the suppressive effects of Treg cells to bolster antitumor immune responses.

Immunotoxins, which couple the specificity of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) with a highly lethal cellular toxin, have been used to selectively eliminate cell subpopulations in vivo.10 LMB-2 [anti-Tac(Fv)-PE38] is a single-chain Fv fragment of the anti-CD25 mAb (Daclizumab [ZENAPAX]) fused to a truncated form of the bacterial toxin Pseudomonas exotoxin (PE).10–12 LMB-2 administered to mice bearing CD25+ human tumors penetrated into the tumors and produced complete tumor regression.13 Similarly, in phase I trials, LMB-2 administration induced clinical responses in patients with CD25+ hematologic malignancies, including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, hairy cell leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Hodgkin disease, and adult T-cell leukemia.14,15 In the current study, LMB-2 was evaluated for the ability to eliminate CD25+ Treg cells selectively from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in vitro. Here, we demonstrate that treatment of human PBMCs with a recombinant immunotoxin, LMB-2, can specifically target and diminish CD25+ Treg cells in vitro without jeopardizing the functional and proliferative potentials of the remaining effector T-cell precursors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Samples

PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque separation from normal donors after obtaining informed consent and were used fresh or were cryopreserved at 108 cells per vial in heat-inactivated human antibody serum with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide and stored at − 180°C.

Immunotoxins

LMB-2 [anti-Tac(Fv)-PE38] is a single-chain Fv fragment of the anti-CD25 mAb (Zenapax) fused to a truncated form of the bacterial PE A. Clinical grade LMB-2 was produced as previously described in detail elsewhere12,15,16 by the Monoclonal Antibody and Recombinant Protein Production Facility (National Cancer Institute [NCI], Frederick, MD). The investigation new drug (IND) application is held by the Cancer Therapy and Evaluation Program (CTEP) of the NCI. LMB-9 is a disulfide, stabilized, recombinant immunotoxin composed of the variable regions of the light and heavy chains of mAb B3 fused to PE38, which directs the cytotoxic potential of PE38 toward cells expressing the Lewis Y antigen, which is not known to be expressed on normal human PBMCs. LMB-2Asp553 is an immunotoxin composed of the Fv portion of anti-Tac fused to a mutated and thus inactivated PE38 [anti-Tac(Fv)-PE38Asp553]. LMB-9 and LMB-2Asp553 were supplied by Ira Pastan and Robert Kreitman. Anti-Tac antibody (Zenapax) was purchased from Roche Pharmaceuticals (Hoffmann-LaRoche, Nutley, NJ).

Media

PBMCs were cultured in complete media (CM) consisting of RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 2 mM glutamine (Biofluids, Rockville, MD), 25 mM HEPES buffer (Biofluids), 100 U/mL penicillin (Biofluids), 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Biofluids), and 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bioproducts, Woodland, CA).

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry was used to assess the surface expression of selected T-cell markers and was performed as previously described.17 Briefly, cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed into ice-cold buffer, washed, and Fc-receptor blocked with mouse IgG (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). CD25 staining was performed using a PE-conjugated 4E clone (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Cells were then incubated with appropriate fluorochrome-labeled antibodies (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) and relevant isotype controls and washed twice subsequently. FACSCalibur and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) was used for acquisition and analysis.

In Vitro Sensitization

The 10-day in vitro sensitization was carried out as previously described.18 Briefly, after 48 hours of exposure to LMB-2, PBMCs were washed and plated at 3 × 106 per well in 24-well plates with 1 μM soluble peptide (Flu58–66 GILGFVFTL or gp100280–288(288V) YLEPGPVTV) for 10 days. Cells were harvested, washed, and plated in 96-well plates with T2 cells alone or pulsed with peptide at 1 μM. After 24 hours, the supernatant from each well was harvested and interferon-γ (IFNγ) was measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Pierce Endogen, Rockford, IL).

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Levels of messenger RNA (mRNA) Foxp3 were analyzed using the quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as described previously.19 In each experiment, 500 ng total RNA was isolated from CD4-purified lymphocytes using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen USA, Valencia, CA) and reverse-transcribed to prepare complementary DNA (cDNA) using the ThermoScript reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The TaqMan Universal Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) was also used as a template. For β-actin, the forward primer used was 5′-GCGAGAAGATGACCCAGATC-3′, the reverse primer used was 5′-CCAGTAGGTACGGCCAGAGG-3′, and the probe used was 5′-FAM-CCAGCCATGTACGTTGCTATCCAGGC-TAMRA-3′. For Foxp3, the combined primer, probe reagent was used (Assay-on-demand gene expression assay, Applied Biosystems). The ABI Prism 7700 detection system (Applied Biosystems) was used with the following settings: 50°C for 2 minutes, followed by 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute.

Lymphocyte Separation

CD4+ cells were separated from whole PBMCs by magnetic bead selection using the Dynal CD4 negative isolation kit (Dynal Biotech; Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In indicated experiments, CD4+ T cells were enriched using the Dynal CD4 positive isolation kit (Dynal Biotech; Invitrogen). For suppression assays, CD4+ cells were further purified into CD25− and CD25+ fractions using the Dynal Treg kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Separations were performed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% bovine serum albumin.

Proliferation Assay

PBMCs treated with 0 or 100 ng/mL LMB-2 for 48 hours were plated in 96-well plates coated with anti-CD3 (1 μg/mL) at a cell concentration of 50 × 103 PBMCs per well. On days 2 and 4 of cell culture, 1 μCi [3H]-thymidine incorporation was added per well and further cultured for 18 hours before harvesting for measurement on days 3 and 5. Plates were harvested onto nylon filters using the Betaplate system, and radioactivity was quantified using a Betaplate counter. Results are expressed as the mean counts per minute of 24 cultures ± standard error of measure (SEM) per condition.

RESULTS

Impact of LMB-2 on Resting Lymphocytes

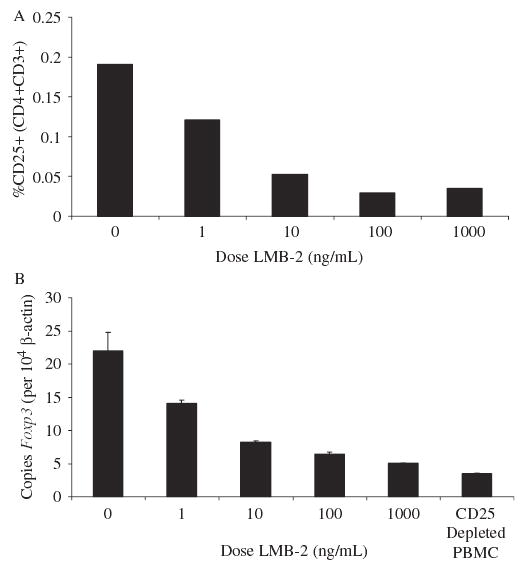

Doses of LMB-2 ranging from a final concentration of 0 to 1000 ng/mL were incubated in vitro with resting PBMCs for 48 hours. The surface expression of CD25 on CD3+CD4+ lymphocytes within this population decreased by 75% to 90% (Fig. 1A), which was paralleled by the decrease in Foxp3 expression (see Fig. 1B). Resting PBMCs were sensitive to LMB-2 at 1 ng/mL, but a maximum impact was observed between 100 and 1000 ng/mL. This experiment was representative of several dose titrations performed. For the remainder of our in vitro experiments, 100 ng/mL was chosen as the treatment dose.

FIGURE 1.

Varying doses of LMB-2 were incubated with resting human PBMCs for 48 hours, and the percentages of residual CD4+CD25+ cells (top) and the copies of Foxp3 mRNA per 104 copies of β-actin mRNA (bottom) were evaluated. A dose-related reduction in these 2 surrogate markers of human Treg cells was seen.

To determine the optimal exposure time, PBMCs were harvested at 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours (data not shown). Based on the decrease in CD25 expression and reduction in Foxp3 expression, 48- or 72-hour exposure was deemed equally appropriate and superior to the shorter exposures after a single administration of LMB-2 at time 0. For the remainder of our in vitro experiments, a 48-hour harvest was used.

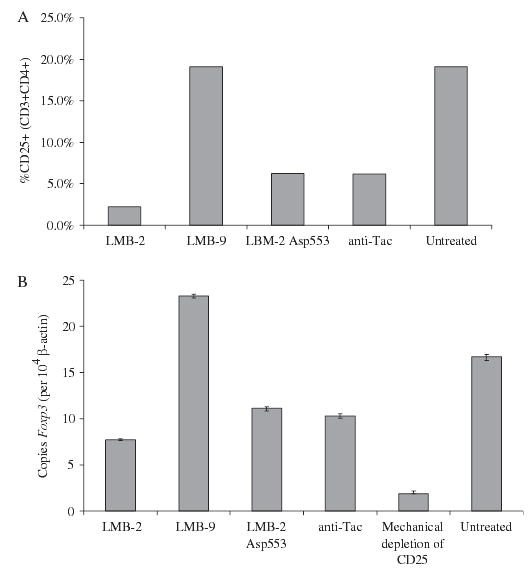

Specificity of LMB-2

Several immunotoxin controls were used to examine the specificity of LMB-2 cytotoxicity toward resting PBMCs. LMB-2Asp553 is identical to LMB-2 except for a single modification (E553D) of PE38 that nearly eliminates adenosine diphosphate (ADP) ribosylation activity. Unmodified anti-Tac antibody,20,21 which is not fused to toxin, was also used as a control. Finally, PBMCs mechanically depleted of CD25+ cells were also used as a control to assess the nadir of Foxp3 expression. Figure 2 shows the impact of LMB-2, LMB-9, LMB-2Asp553, and anti-Tac (each at 100 ng/mL) on CD25 surface expression and Foxp3 expression, respectively. LMB-9 had no impact on PMBCs, suggesting that the cytotoxicity of LMB-2 was directed toward cells expressing CD25 rather than killing because of nonspecific internalization of PE38. LMB-2Asp553 and anti-Tac had a similar impact on resting CD3+CD4+ PBMCs, reducing CD25 expression from 19.1% to 6.2% and 6.2%, respectively, and reducing Foxp3 expression from 16.7 to 11.1 and 10.3 copies per 104 β-actin copies. LMB-2 had a superior depleting effect, reducing CD25 expression to 2.2% and Foxp3 expression to 7.2 copies. This experiment was performed twice with similar results. The observed reductions in CD25 and Foxp3 expression by LMB-2Asp553 and anti-Tac suggest that blockade of the α-chain of the IL-2 receptor on resting CD4+CD25+ cells may be detrimental to their survival, although not to the extent resulting from internalization of the toxin. Finally, the Foxp3 expression in PBMCs mechanically depleted of CD25+ cells showed even greater depletion, underscoring the partial depletion by LMB-2.

FIGURE 2.

Resting human PBMCs were incubated in vitro for 48 hours with 100 ng/mL of LMB-2, LMB-9 (an immunotoxin that recognized the Lewis Y antigen not expressed on PBMCs), LMB-2Asp553 (anti-CD25 fused to an inactivating mutation in the Pseudomonas exotoxin), or the intact anti-Tac mAb. Some decrease in the percentage of CD4+ CD25+ cells and/or Foxp3-expressing cells was seen with LMB-9, LMB-2Asp553, and anti-Tac. A greater decrease was seen in PBMCs treated with LMB-2, although it did not reach the level of Foxp3 depletion achieved by ex vivo mechanical depletion using anti-CD25 magnetic leads.

Impact of LMB-2 on CD4+CD25+ Regulatory T Cells

To quantify the impact of LMB-2 on resting Treg cells, large numbers of freshly isolated PBMCs were treated with or without LMB-2. After 48 hours of incubation, PBMCs were counted and mechanically sorted into CD4+ fractions by negative isolation and then into CD4+CD25− and CD4+CD25+ fractions. Table 1 shows the absolute cell counts for each cell subset from 2 independently performed experiments on separate patient samples. In the first experiment, 1.5 × 109 PMBCs were treated in flasks with no treatment or 100 ng/mL LMB-2 for 48 hours. The impact of LMB-2 on the absolute CD4+ count and the absolute CD4+CD25− count was minimal (decrease of 14.4% and 1.9%, respectively). The decrease in CD4+CD25+ cells was more profound (98.7% reduction), however. In the second experiment, starting with one fifth the total number of PBMCs compared with the first experiment, a greater reduction in was seen in the treated CD4+ fraction (47.9%), whereas an increase was observed in the absolute count of CD4+CD25− cells (27.4%). A similar reduction in absolute CD4+CD25+ cell count as seen in the first experiment was observed (98.7%), however.

TABLE 1.

LMB-2 Mediated Reduction of CD25 Expressing Cells in Human PBMC

|

Patient 1 |

Patient 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | LMB-2 | Untreated | LMB-2 | |

| Fresh PBMC | 1500 | 1500 | 300 | 300 |

| 48 hour PBMC | 1305 | 1190 | 230 | 278 |

| Isolated CD4+ | 160 | 137 | 38.4 | 20.4 |

| Isolated CD4+ CD25− | 106 | 104 | 9.9 | 12.6 |

| Isolated CD4+ CD25+ | 5.1 | 0.067 | 0.15 | <0.002 |

| Reduction in CD4+ CD25+ (%) | 98.7% | 98.7% | ||

Fresh patient pheresis samples (PBMC) were cultured in T175 flasks at 4 × 106 cells/mL in CM with or without LMB-2 (100 ng/mL). After 48 hours, PBMC were counted and mechanically sorted into CD4+ fractions by negative magnetic selection. Subsequently, CD4+ enriched cells were counted and separated into CD25+ and CD25− fractions and enumerated. Upper values represent the absolute number (× 10−6) of treated or untreated PBMC before and after subset separations. Percent LMB-2 mediated reduction in CD4+ CD25+ cell number was calculated as 1 − (LMB-2 treated CD4+ CD25+ count ÷ untreated CD4+ CD25+ count).

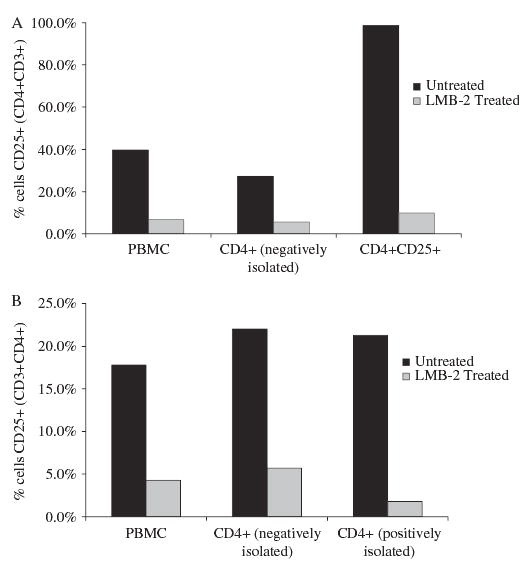

Using flow cytometry, surface expression of CD25 was measured on the treated PBMCs in addition to posttreated purified subsets (CD4+ cells isolated by negative selection, CD4+ cells isolated by positive selection, and CD4+CD25+ cells). Figure 3A shows the reduction in CD25 expression on PBMCs, negatively isolated CD4+ cells, and CD4+CD25+ cells. Figure 3B shows the reduction in CD25 expression on PBMCs as well as on negatively and positively isolated CD4+ cells from a second representative experiment. In both experiments, the reduction in CD25 expression, regardless of the method of posttreatment isolation, was between 80% and 95%.

FIGURE 3.

Resting human PBMCs were incubated with LMB-2 for 48 hours, and the percentage of CD4+CD25+ cells remaining was evaluated by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis. A significant decrease in CD25-expressing cells was seen as a result of LMB-2 treatment in whole PBMCs and negatively isolated purified CD4+CD25+ cells (top). A similar decrease was seen in a second experiment testing negatively and positively isolated CD4+ cells (bottom).

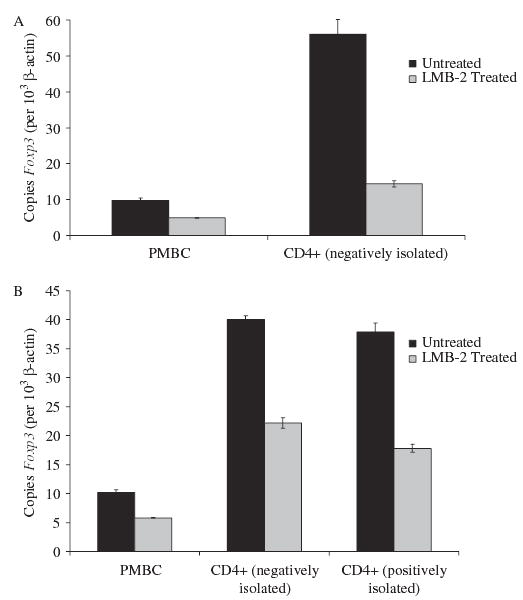

Total RNA was isolated from the cells from these experiments, and real-time quantitative PCR was used to quantify Foxp3 expression, relative to β-actin, in the treated PBMCs and posttreated isolated cell subsets (Fig. 4). In both experiments, the reduction in Foxp3 expression in whole PBMCs was approximately 50%, whereas in CD4+ subsets, the reduction varied from 50% to 75%.

FIGURE 4.

Same cells as in Figure 3. LMB-2 treatment also reduced Foxp3 levels in PBMCs and in purified CD4+ cells.

Impact of LMB-2 on Non-CD25+ Bystander Cells

The impact of LMB-2 on the surviving non-CD4+CD25+ cells was examined using proliferation (Table 2) and in vitro peptide sensitization assays (Table 3). PBMCs were harvested after 48 hours of exposure to 0 or 100 ng/mL LMB-2 and plated in 96-well plates that had been coated with anti-CD3 (1 μg/mL) at a cell concentration of 50 × 103 PBMCs per well. On days 3 and 5 of cell culture, [3H]-thymidine incorporation was measured (see Table 2). On day 3, the untreated PBMCs seemed to have a proliferative advantage compared with the treated PBMCs; however, LMB-2–treated and –untreated PBMCs had proliferated equivalently by day 5 of culture. It is unclear whether the recovery of day 5 LMB-2–treated PBMCs reflects a continued growth of non-CD25+ PBMCs or the efficient incorporation of [3H]-thymidine by remnant CD25+ cells not eliminated by LMB-2.

TABLE 2.

Proliferation of LMB-2 Treated PBMC

|

Pre-Treatment |

||

|---|---|---|

| Age of Culture | Untreated | LMB-2 |

| Day 3 | 73.7 ± 1.2 | 48.6 ± 2.3 |

| Day 5 | 74.0 ± 1.2 | 75.3 ± 1.2 |

PBMC, pretreated with 0 or 100 ng/mL LMB-2 for 48 hours, were plated at 5 × 104 cells per well in 96-well plates precoated with anti-CD3 (1 μg/mL). Cells were cultured, in the presence of 1 μCi [3H]-thymidine for the final 18 hours, for 3 and 5 days and harvested onto nylon filters for assessment of proliferation by betacount. Values indicate the mean counts per minute (CPM) of 24 cultures ± SEM per condition.

TABLE 3.

The Function of Effector Cell Precursors Is not Affected by LMB-2 Exposure

|

Pre-Treatment |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Untreated |

LMB-2 |

|||||

| Stimulation | None | g280 | Flu | None | g280 | Flu |

| Flu/T2 | 104 | 42 | 799 | 178 | 174 | 626 |

| g280/T2 | 76 | 31 | 54 | 115 | 107 | 174 |

| T2 alone | 155 | 112 | 129 | 231 | 210 | 326 |

| None | 119 | 121 | 131 | 102 | 94 | 147 |

PBMC were pretreated with 0 or 100 ng/mL LMB-2 for 48 hours, washed and cultured for 10 days at 3 × 106 cells per well in 24-well plates with IL-2 (50 CU/mL) alone or with 1 μM soluble peptide (Flu: Flu58–66, GILGFVFTL; gp100:gp100280–288(288V), YLEPGPVTV). After 10 days, cells were washed, and co-cultured overnight with an equivalent number (1 × 105) of T2 cells alone or pulsed with 1 μM of the indicated peptide. Values indicate the concentration of gamma-interferon (pg/mL) secreted in response to stimulation as measured by standard ELISA. Values in bold denote concentrations twice background and ≥ 200 pg/mL.

To examine the ability of surviving PBMCs to respond to peptide stimulation, LMB-2–treated and –untreated PBMCs were cultured with relevant (Flu58–66), irrelevant (gp100280–288 (288V)), or no soluble peptide for 10 days. The cells were then washed and plated with T2 cells pulsed with and without each peptide overnight, and IFNγ secretion in the supernatant was measured (see Table 3). LMB-2–treated PBMCs responded to relevant peptide stimulation to a similar extent as the untreated PBMCs, suggesting that LMB-2 had no deleterious effects on the remaining CD4+ and CD8+ non-CD25+ cells.

DISCUSSION

Murine models have demonstrated that that elimination of Treg cells can augment the antitumor efficacy of the adoptive transfer of antitumor T cells.9,22 Conversely, the addition of Treg cells can inhibit the antitumor impact of cell transfer.9 In humans, adoptive immunotherapy strategies that involve a nonmyeloablative lymphodepleting chemotherapy regimen before cell transfer induce an objective response rate of approximately 50% in patients with metastatic melanoma.23,24 One plausible explanation for the success of this treatment lies in the elimination of host Treg cells by lymphodepletion before cell infusion. A host homeostatic environment devoid of Treg cells and competing cells can influence the efficacy of tumor vaccination as well. Mice immunized with tumors in the absence of CD4+CD25+ cells generated immunity against these tumors.25 Further, tumor-specific T cells preferentially expanded in the lymphopenic environment after a melanoma vaccine was administered to RAG1-deficient mice reconstituted with naive T cells from normal mice.26 The fact that simply removing Treg cells can allow effector T cells to display their innate antitumor capabilities suggests that Treg cells may paradoxically protect tumors from the host by inhibiting effector T cells from recognizing or responding to the antigenic stimulus. Because many cancer antigens are derived from nonmutated self-proteins,27 Treg cells that may be playing a role in protection from autoimmunity may also be inhibiting antitumor responses.

The ability to surmount peripheral self-tolerance may be important to mediate in vivo antitumor responses in cancer patients. Overcoming the immunoregulatory influences of Treg cells in vivo requires clinical-grade reagents with specific targeting and elimination of Treg cells.19 Recombinant immunotoxins and cytotoxins have been shown to deliver a cytotoxic signal targeted by the specificity of mAbs or growth factor ligands, respectively.28 In phase I trials, immunotoxins and cytotoxins have demonstrated clinical effectiveness against malignancies expressing CD22, CD122, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor (GM-CSFR), IL-13 receptor, IL-2 receptor, and CD25.10 Because CD25, CTLA-4, and GITR represent cell surface markers of resting Treg cells to which clinical reagents can be targeted, we have initiated the evaluation of clinical-grade reagents that target these molecules on Treg cells.

We have recently treated patients with a fusion protein, Denileukin Diftitox (ONTAK), which enzymatically links the active portion of the diphtheria toxin to IL-2.29 Because Treg cells constitutively express the high-affinity α-chain CD25, it was hypothesized that treatment with Denileukin Diftitox would specifically expose these resting CD25-expressing cells to the potent toxicities of diphtheria toxin. Thirteen patients with metastatic cancer (12 with melanoma, 1 with renal cell carcinoma) were treated with the approved low dose (9 μg/kg) or high dose (18 μg/kg) of Denileukin Diftitox without any regression of cancer or impact on Treg cells.30 In some patients, the frequency of CD4+CD25+ cells increased, as did normalized levels of Foxp3 expression. In addition, there was no evidence that the suppressor function of posttreatment Treg cells had decreased compared with pretreatment Treg cells. Because IL-2 is a homeostatic cytokine for Treg cells,31 the inability of Denileukin Diftitox to eliminate Treg cells may result from the ligand triggering effect of the IL-2 portion of the fusion protein. Indeed, in previous studies, treatment of IL-2 receptor-positive T cells with IL-2–based toxin in vitro initially mimicked the stimulatory effects of IL-2 on gene transcription and DNA synthesis, yet concomitant inhibition of protein synthesis was evident.32,33 Based on our efforts with Denileukin Diftitox, we hypothesized that an antibody rather than a stimulating ligand may be a more suitable means to target CD25+ cells.

Whereas the anti-Tac mAb can target CD25+ alloreactive and malignant lymphocytes in vivo, the long half-life of the antibody in vivo (2–3 weeks) prevents its application in cancer immunotherapy, where developing activated antitumor T cells may also express CD25 and be destroyed.34 In a phase I trial of LMB-2 administration, the median peak plasma level of LMB-2 was approximately 600 ng/mL, with a mean half-life of 4.5 hours at the maximum tolerated dose.15 The short half-life of the LMB-2 immunotoxin in vivo provides the possibility of eliminating Treg cells and then administering agents such as IL-2 or cancer antigen vaccines once the immunotoxin has been cleared.15

In the current study, we have shown that treatment with the LMB-2 immunotoxin targeting the CD25 molecule on Treg cells can selectively eliminate Treg cells in vitro without impairing the function of the remaining cells. An 8.5-fold reduction in CD25-expressing CD4+ T cells and a 3-fold reduction in Foxp3 mRNA expression by enriched CD4+ T cells were seen after 48 hours of LMB-2 incubation compared with LMB-9 control. The disconnect between CD25 and Foxp3 reduction levels may reflect the coelimination of a small fraction of activated CD25-expressing CD4+ T cells that do not express Foxp3, although selective survival of CD25+ cells with higher Foxp3 levels is also possible. Indeed, the depletion of Treg cells is not complete based on the evaluation of CD25 and the surrogate marker Foxp3. Given that LMB-2 can reduce Treg cells in vitro, however, LBM-2 administration may provide meaningful improvement to current immunotherapeutic approaches, particularly with repeated dosing. These studies have provided the preclinical framework for the design of clinical trials to evaluate the ability of LMB-2 to eliminate Treg cells in vivo in humans.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

References

- 1.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory T cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:531–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:345–352. doi: 10.1038/ni1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F, et al. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet. 2001;27:20–21. doi: 10.1038/83713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Javia LR, Rosenberg SA. CD4+CD25+ suppressor lymphocytes in the circulation of patients immunized against melanoma antigens. J Immunother. 2003;26:85–93. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200301000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang HY, Lee DA, Peng G, et al. Tumor-specific human CD4+ regulatory T cells and their ligands: implications for immunotherapy. Immunity. 2004;20:107–118. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viguier M, Lemaitre F, Verola O, et al. Foxp3 expressing CD4+CD25(high) regulatory T cells are overrepresented in human metastatic melanoma lymph nodes and inhibit the function of infiltrating T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:1444–1453. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Overwijk WW, Theoret MR, Finkelstein SE, et al. Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self-reactive CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antony PA, Piccirillo CA, Akpinarli A, et al. CD8+ T cell immunity against a tumor/self-antigen is augmented by CD4+ T helper cells and hindered by naturally occurring T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:2591–2601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreitman RJ. Recombinant immunotoxins for the treatment of haematological malignancies. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:1115–1128. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.7.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhary VK, Queen C, Junghans RP, et al. A recombinant immunotoxin consisting of two antibody variable domains fused to Pseudomonas exotoxin. Nature. 1989;339:394–397. doi: 10.1038/339394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreitman RJ, Batra JK, Seetharam S, et al. Single-chain immunotoxin fusions between anti-Tac and Pseudomonas exotoxin: relative importance of the two toxin disulfide bonds. Bioconjug Chem. 1993;4:112–120. doi: 10.1021/bc00020a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreitman RJ, Bailon P, Chaudhary VK, et al. Recombinant immunotoxins containing anti-Tac(Fv) and derivatives of Pseudomonas exotoxin produce complete regression in mice of an interleukin-2 receptor-expressing human carcinoma. Blood. 1994;83:426–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreitman RJ, Wilson WH, Robbins D, et al. Responses in refractory hairy cell leukemia to a recombinant immunotoxin. Blood. 1999;94:3340–3348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreitman RJ, Wilson WH, White JD, et al. Phase I trial of recombinant immunotoxin anti-Tac(Fv)-PE38 (LMB-2) in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1622–1636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.8.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreitman RJ, Pastan I. Purification and characterization of IL6-PE4E, a recombinant fusion of interleukin 6 with Pseudomonas exotoxin. Bioconjug Chem. 1993;4:581–585. doi: 10.1021/bc00024a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phan GQ, Yang JC, Sherry RM, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity induced by cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8372–8377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533209100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Schwartzentruber DJ, et al. Impact of cytokine administration on the generation of antitumor reactivity in patients with metastatic melanoma receiving a peptide vaccine. J Immunol. 1999;163:1690–1695. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell DJ, Jr, Parker LL, Rosenberg SA. Large-scale depletion of CD25+ regulatory T cells from patient leukapheresis samples. J Immunother. 2005;28:403–411. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000170363.22585.5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waldmann TA, White JD, Goldman CK, et al. The interleukin-2 receptor: a target for monoclonal antibody treatment of human T-cell lymphotrophic virus I-induced adult T-cell leukemia. Blood. 1993;82:1701–1712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waldmann TA, Goldman CK, Bongiovanni KF, et al. Therapy of patients with human T-cell lymphotrophic virus I-induced adult T-cell leukemia with anti-Tac, a monoclonal antibody to the receptor for interleukin-2. Blood. 1988;72:1805–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antony PA, Restifo NP. CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells, immunotherapy of cancer, and interleukin-2. J Immunother. 2005;28:120–128. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000155049.26787.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298:850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1076514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, et al. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2346–2357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones E, Golgher D, Simon AK, et al. The influence of CD25+ cells on the generation of immunity to tumour cell lines in mice. Novartis Found Symp. 2004;256:149–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu HM, Poehlein CH, Urba WJ, et al. Development of antitumor immune responses in reconstituted lymphopenic hosts. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3914–3919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenberg SA. A new era for cancer immunotherapy based on the genes that encode cancer antigens. Immunity. 1999;10:281–287. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kreitman RJ. Recombinant toxins for the treatment of cancer. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2003;5:44–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waters CA, Schimke PA, Snider CE, et al. Interleukin 2 receptor-targeted cytotoxicity. Receptor binding requirements for entry of a diphtheria toxin-related interleukin 2 fusion protein into cells. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:785–791. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Attia P, Maker AV, Haworth LR, et al. Inability of a fusion protein of IL-2 and diphtheria toxin (Denilukin Diftitox, ONTAK) to eliminate regulatory T lymphocytes in patients with melanoma. J Immunother. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Malek TR. The main function of IL-2 is to promote the development of T regulatory cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:961–965. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0603272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walz G, Zanker B, Murphy JR, et al. A kinetic analysis of the effects of interleukin-2 diphtheria toxin fusion protein upon activated T cells. Transplantation. 1990;49:198–201. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199001000-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walz G, Zanker B, Brand K, et al. Sequential effects of interleukin 2-diphtheria toxin fusion protein on T-cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9485–9488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vincenti F, Nashan B, Light S. Daclizumab: outcome of phase III trials and mechanism of action. Double Therapy and the Triple Therapy Study Groups. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:2155–2158. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]